Neuroretinitis

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Neuroretinitis is a focal inflammation of the optic nerve and peripapillary retina or macula of either infectious or idiopathic etiology.

Disease Entity

Neuroretinitis ICD9 363.05; ICD10 H30.893

Disease

Neuroretinitis is an inflammation of the neural retina and optic nerve. It was originally described by Leber in 1916 as a "stellate maculopathy," but this definition was challenged by Don Gass in 1977, citing that disc edema precedes macular exudates. Subsequently, Gass confirmed optic disc leakage by fluorescein angiography and suggested the term "neuroretinitis." More recent retinal and optic nerve imaging has supported Gass' description.

Risk Factors

Risk factors for neuroretinitis relate to susceptibility to each particular causative agent. Patients immunocompromised from chronic disease, HIV/AIDS, medications, health care workers, recent immigrants or those with recent travel to endemic areas are all high-risk populations.

General Pathology

Direct invasion or autoimmune activation against the optic nerve may cause optic nerve vascular inflammation with secondary inflammation and edema in the nerve fiber layer of the retina.

Pathophysiology

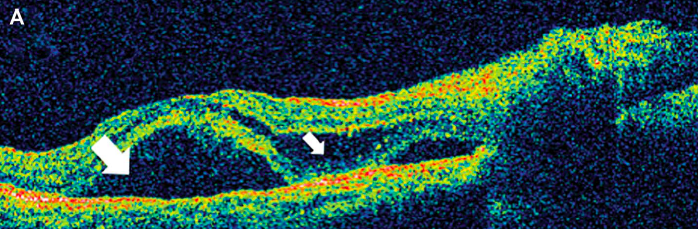

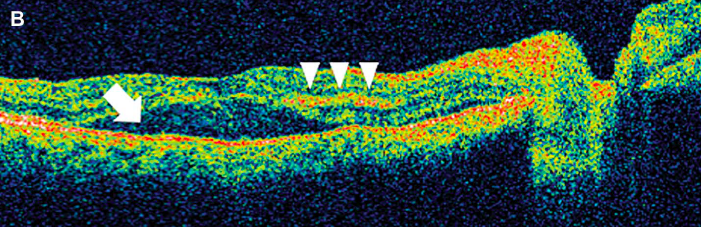

Neuroretinitis is characterized by an inflammation of the optic disc vasculature with exudation of fluid into the peripapillary retina. The lipid-rich component of the exudate is further able to penetrate into the outer plexiform layer, creating what is clinically seen as a macular star pattern. Only the aqueous phase is then able to pass through the external limiting membrane to accumulate beneath the neurosensory retina (Figure 2, large arrow). The exact origin of the inflammation of the optic disc vasculature is unclear. A flu-like prodrome in some patients supports a viral etiology: either a virally-induced autoimmune response or direct invasion of the nerve. One case report has cited autopsy findings of herpes simplex virus in the optic nerve substance.

Figure 2. Macular OCT showing thickening in different layers of retina. Small arrow shows location of Henle's layer, where exudates are deposited (see Figure 6). These exudates are seen clinically as the macular star pattern. The large arrow shows subretinal fluid causing local neurosensory retinal detachment.

Classification

Neuroretinitides can be divided into those in which a specific infectious agent has been identified, those considered idiopathic, and those which are idiopathic with recurrent attacks. Importantly, the diagnosis of neuroretinitis is not considered a risk factor for the future development of multiple sclerosis.

Infectious Neuroretinitis

Most infectious cases are due to cat-scratch disease, caused by Bartonella species. In a review article by Purvin et al., review of literature shows an average age of onset is 24.5 years with a range from 4 to 64 years and a female:male incidence of 1.8:1. Seventy-three percent of these patients manifest systemic symptoms, while only 7.7% manifest eye pain. Usually the feline is a kitten rather than an older cat. Up to 40 percent of cats carry the bacteria at some time in their lives, yet most commonly when they are kittens. Common systemic symptoms include a bump or blister at the bite or scratch site, swollen lymph nodes, fatigue, headaches and of course a fever, hence the term scratch fever. The most dire complication is encephalitis.

Initial visual acuity is 20/200 or worse in 52% of patients, while final visual acuity is 20/40 or better in 93%. Eighty-eight percent have a central visual field defect, and 67.5% manifest a relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD). One study reported seven eyes with count finger visual acuity and no RAPD, suggesting that visual impairment in neuroretinitis is due to macular pathology rather than optic nerve dysfunction. Vision in these seven patients returned to 20/40. Most cases are unilateral but bilateral cases have been reported.

In cases of neuroretinitis caused by cat scratch disease seen acutely, treatment with a broad-spectrum antibiotic is reasonable while serologic tests are pending, especially in cases with findings suggestive of an infectious cause (if exposure to kittens). A physical exam to look for a scratch or blister may provide supportive evidence. Azithromycin treatment can be used in both children and adults.

Other infectious diseases implicated include syphilis, Lyme disease, Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, toxoplasmosis, toxocariasis, histoplasmosis, and leptospirosis. Syphilis, Sarcoidosis and TB also remain in the differential diagnosis of neuroretinitis.

Idiopathic and Recurrent Idiopathic Neuroretinitis

Cases in which a clear infectious or inflammatory etiology is not found are categorized as idiopathic. Average age of onset in these cases is 28 years with a range from 8 to 55 years of age. In published cases, more than 50% have a preceding flu-like illness, usually an upper respiratory infection (URI). Visual loss is usually painless.

Most cases of visual loss are unilateral and vision is usually between 20/50 and 20/200, though vision has been shown to range from 20/20 to light perception only (LPO). The most common visual field loss pattern is a central or cecocentral scotoma from edema of the papillomacular bundle. Though an RAPD may be present, it is not as prominent as in demyelinating disease.

Examination usually manifests posterior chamber cells and occasionally anterior chamber cell and flare. Early in the course of the disease, the fundus shows isolated optic disc edema with exudative peripapillary serous retinal detachment. After 9-12 days, macular edema is present and disc edema is diminished. Over time, exudates become less well-defined, then disappear, and, finally, only RPE defects remain. At 8-12 weeks, the disc edema has resolved, leaving a normal or pallorous nerve.

Most patients with idiopathic neuroretinitis recover excellent visual acuity with or without intervention: 20/40 or better in 90% of reported cases. One small subset in a case series fared poorly with large disc-related defects and APD; the authors attributed these findings to a vaso-occlusive mechanism of prelaminar arterioles with subsequent disc infarction.

Treatment choice is unclear. One report documents use of intravitreal steroids and bevacizumab. Patients in this report were diagnosed with idiopathic neuroretinitis ten days after vision initially decreased and received treatment three days after. Vision had returned to baseline and macula appeared normal at one week, and the disc appeared normal at one month. Since two treatments were administered, and since the natural course of the disease is recovery anyway, assessing efficacy of treatment is difficult.

Some cases of idiopathic neuroretinitis are recurrent. In these cases, visual loss tends to be more related to optic disc disease with central and nerve fiber layer-related visual defects. Recurrence tends to result in an optic neuropathy with less visual and field recovery. Hard exudates are less prominent in subsequent attacks. The majority of reported cases of recurrent neuroretinitis are idiopathic. In patients with recurrence, long-term immunosuppressive treatment should be considered. For the acute event consider a short course of corticosteroids.

Primary Prevention

Avoidance of exposure to causative agents, infected individuals, and high-risk areas and practices limit susceptibility to causative bacterial and viral agents. Careful handling of kittens, if scratched, wash the would as soon as possible.

Diagnosis

Complete history and ophthalmologic physical exam should be performed. Additional testing, such as full systemic physical exam or ancillary testing should be guided by clinical suspicion.

Clinical Evaluation

History

Time of onset, laterality, and duration of symptoms should be elicited on examination. A history of similar episodes may be noteworthy. Social history, particularly for history of recent travel, contact with sick individuals or animals, and sexual activity should be documented. Review of systems to assess pulmonary status, skin changes, cardiovascular issues, unintentional weight changes, and constitutional symptoms should be sought. If brainstem signs are evident, patient should be asked about nausea, vomiting, hearing difficulty, tinnitus, dysphagia, dysphonia, and syncope. Depending on acuity of visual loss and quality of vision change, questions should be asked to rule out giant cell arteritis. Patients may also be asymptomatic.

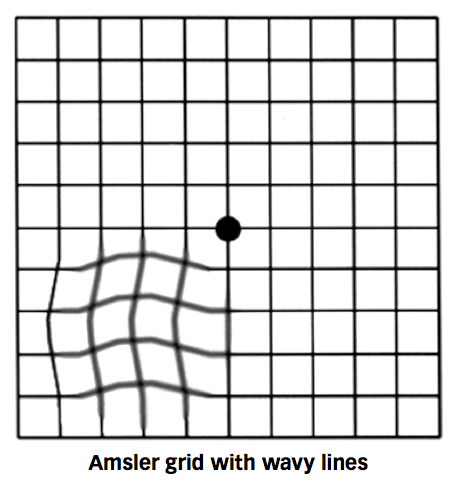

Physical Examination

An ophthalmologic examination should be performed including blood pressure (checking for hypertensive retinopathy), acuity, color vision testing, automated visual fields or Amsler grid, pupillary evaluation checking for a relative afferent pupillary defect and a fundus examination. A complete exam will assist in diagnosing optic nerve or localizing macular pathology. Fluorescein angiography may be performed to assess for disc leakage or vascular pathology within the macula.

Signs

External exam for evidence of skin lesions should be performed. Lids and lashes should be examined for herpetic lesions. Anterior segment should be evaluated for keratic precipitates, anterior chamber reaction, iris nodules, posterior synechiae, or anterior vitritis. Optic disc should be evaluated for pallor, and vasculature for sheathing or perivascular hemorrhage. Macula may manifest hard exudates in a star pattern with associated retinal thickening or subretinal fluid.

Symptoms

Patients may exhibit painless decrease in central vision, decreased color vision, or, occasionally, may be asymptomatic.

Clinical Diagnosis

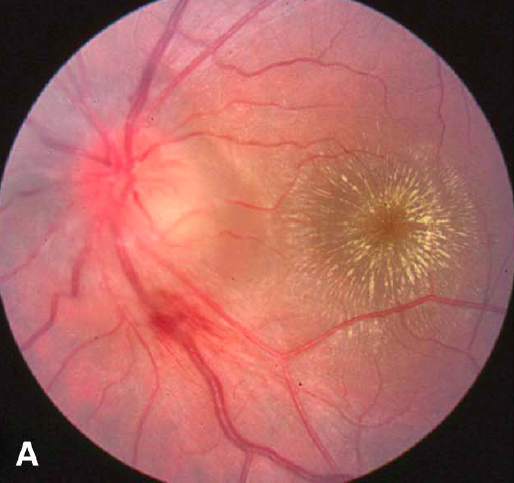

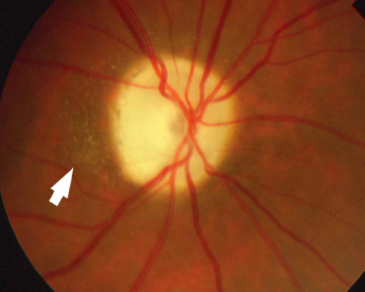

Direct or indirect fundus examination of the posterior pole may reveal an inflamed optic disc and/or a macular star pattern. As the macular star may take 1-2 weeks to manifest, only optic disc inflammation may be evident in an early presentation. Macular star generally becomes apparent a few weeks (Left) after onset of visual symptoms and resolves thereafter over several weeks. In a recurrent episode, a macular star may or may not be evident and even if present may not exhibit classic star pattern (Middle, Right). Hard exudates in a somewhat radial pattern relative to the fovea may be the only obvious finding. Chronically disc pallor may be present.

Figure 4. (Left) Classic macular star pattern. (Middle, Right) Irregular pattern of exudates in recurrence of neuroretinitis.

Diagnostic procedures

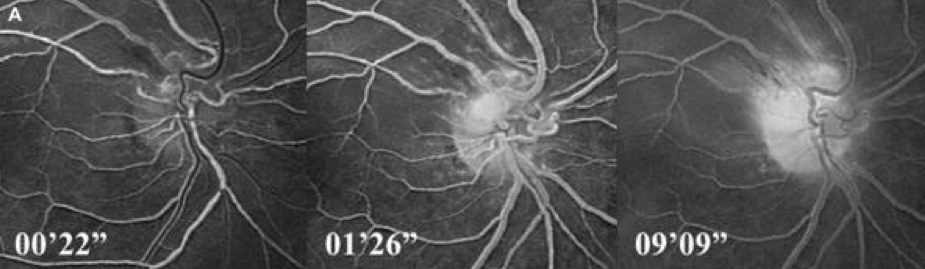

Fluorescein angiography may reveal disc edema and leakage and blockage of fluorescence in areas of hard exudates. Occasionally, staining may be found in the seemingly uninvolved contralateral eye.

Figure 5. Time lapse images of fluorescein angiography showing progressive leakage of single vessel from an inflamed disc in neuroretinitis.

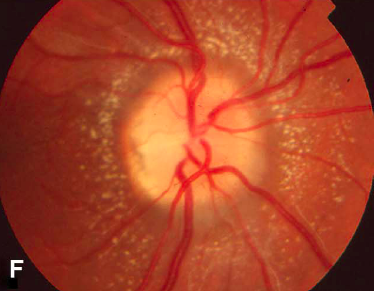

Optical coherence tomography reveals retinal thickening, possible subretinal fluid (large arrow), and fluid or exudates (arrowheads) within the outer plexiform layer (Henle's layer). OCT may also be useful in detecting a serous retinal detachment before a macular star forms. It may also be useful the minority of cases in which a star never forms. Autofluorescence may assist in detecting macular exudates.

Figure 6. Large arrow shows neurosensory retinal detachment from fluid that has diffused through all retinal layers. Arrowheads draw attention to orange flecks representing exudates in Henle's layer, seen clinically as a macular star.

Laboratory test

Laboratory testing should be guided by clinical suspicion and tailored to history and physical examination. In general, a comprehensive infectious and inflammatory work-up should be undertaken. By frequency, cat-scratch titers should be obtained. FTA-ABS, PPD (Picture) or serologic testing with interferon gamma release assay, Lyme serology, ACE & lysozyme, Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (RMSF) testing and chest x-ray (2 views) may serve as adequate baseline tests.

Figure 7. Positive PPD in patient with neuroretinitis from tuberculosis.

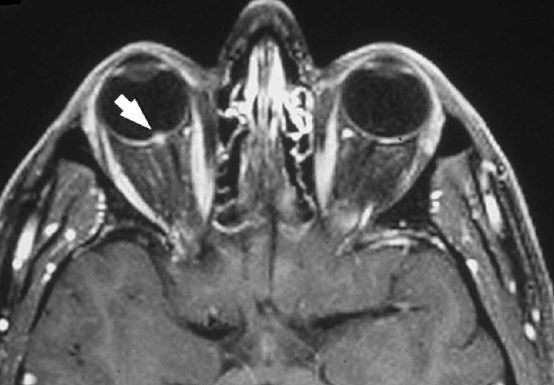

Imaging

In general, neuroimaging studies in neuroretinitis are normal and not generally required for diagnosis. There are few reports of abnormal neuroimaging studies in patients with neuroretinitis in which the MRI demonstrated abnormalities of the optic nerve . The fat-suppressed contrasted enhanced axial T1 weighted orbital MRI below shows right intravitreal optic nerve enhancement (arrow) which would be expected with severe disc edema. Retrobulbar enhancement (like in optic neuritis) is rare, but reported.

Hence, there appears to be a spectrum of neuroimaging findings in neuroretinitis:

- Normal optic nerve

- Intraocular optic disc enhancement at the nerve-globe junction (below)

- Optic nerve sheath enhancement (optic perineuritis)

- Optic nerve and optic sheath enhancement

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnosis for macular star includes hypertensive retinopathy, papilledema, anterior ischemic optic neuropathy, diabetic papillopathy, posterior vitreous traction, disc and juxtapapillary tumors, and toxic etiologies, including bis-chloroethyl, nitrosourea and procarbazine. Many of the disease processes in the differential, however, tend to be bilateral in nature, unlike neuroretinitis. As such, clinical suspicion should guide additional testing and diagnosis.

Management

General treatment

The treatment of neuroretinitis is directed at the underlying etiology. Suspicion for infectious etiology, particularly tuberculosis, may merit consultation with an infectious disease specialist. If causative agent is found to be cat-scratch disease, various treatment methods are found in the literature, including no treatment, antibiotics only, antibiotics and steroids, and steroids only. As a high degree of spontaneous visual recovery exists in cat-scratch disease neuroretinitis, definite conclusions cannot be made regarding antibiotic efficacy.

If an infectious etiology is suspected, appropriate work-up with broad spectrum antibiotic treatment while results are pending is appropriate. Recommended antibiotics are ciprofloxacin or azithromycin for adults and azithromycin or sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim for children. For the idiopathic variety, high-dose oral corticosteroids have been administered. Antibiotics may be considered to cover cat scratch disease while serologies are pending.

Medical follow up

If an infectious etiology is suspected but serologies are negative, retesting at six weeks for rising IgG titers is appropriate.

Complications

Complications stem from side effects from pharmacologic therapy or chronic visual loss from recurrence. Anti-tuberculous treatments are well-known for ocular complications, including retrobulbar neuritis with ethambutol and significant anterior uveitis and hypopyon with rifabutin therapy.

Prognosis

Optic disc edema is generally self-limited. Otherwise, another etiology such as disc tumor or sarcoid should be considered. Most patients with idiopathic neuroretinitis achieve excellent visual recovery with or without intervention. In infectious neuroretinitis, one report cites 93% of patients achieving 20/40 final visual acuity or better, and no patients with less than 20/200 vision.

References

- http://www.uptodate.com/contents/diabetic-papillopathy http://webeye.ophth.uiowa.edu/eyeforum/cases/36-CatScratchBartonella.htm

- Fouch B, Coventry S. A case of fatal disseminated Bartonella henselae infection (cat-scratch disease) with encephalitis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131(10):1591-4.

- Ghauri R, Lee A. Optic Disk Edema With a Macular Star. Survey of Ophthalmology. 43(3): 270-4, 1998.

- Purvin VA, Chioran G. Recurrent neuroretinitis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1994;112:365-71.

- Purvin V, Sundaram S, Kawasaki A. Neuroretinitis: Review of the Literature and New Observations. J Neuro-Ophthalmology. 2011;31: 58-68.

- Vaphiades MS. Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever as a cause of macular star figure. Neuroophthalmol. 2003;23(4):276-8.

- Vaphiades MS, Wigton EH, Ameri H, Lee AG. Neuroretinitis with retrobulbar involvement. J Neuroophthalmol. 2011;31(1):12-5.