Toxocariasis

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Ocular toxocariasis is a rare infection caused by roundworms, Toxocara canis and Toxocara cati. It was first recognized to be associated with dogs in the 1940s. It typically affects children and can lead to profound monocular loss of vision despite known medical and surgical therapies. Its prevalence has been estimated in certain populations and found to be rare. Presentations typically include posterior uveitis with symptoms and signs such as reduced vision, photophobia, floaters, and leukocoria. Management includes quieting inflammation, eliminating the offending organism, and repairing vitreoretinal sequelae. Prognosis is often correlated to presentation and the degree to which sequelae are present. Vision typically ranges from 20/40 to 20/400 depending on these factors.

Disease Entity

Toxocariasis ICD9 128.0. This article is specific to the ophthalmic variant, ocular larva migrans (OLM).

Disease

Toxocariasis is a zoonosis, which results from infection with common roundworms Toxocara canis and Toxocara cati. The definitive host is cats and dogs. It exists as two major categorizations, visceral larva migrans (VLM) and ocular larva migrans (OLM). Although seroprevalence as measured by Toxocara antibody levels in the United States has been estimated at 13.9%, symptomatic infection is significantly less common, especially OLM.

Prevalence and Incidence

The prevalence of this disease has been measured in certain subpopulations as well as the general population. In a North Californian uveitic population, 1% of patients were found to have ocular toxocariasis. According to Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report released by the CDC, from September 2009 until September 2010 there were 68 new cases of ocular toxocariasis in the country with an emphasis of new cases from the South (57%).

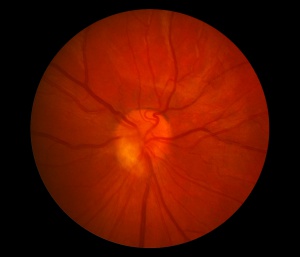

Ocular toxocarasis

Typically, this disease manifests in children and early adolescents but 23 case studies found afflicted patients ranging from 8 to 45 years of age. In 2010 the CDC reported an average age in the United States of 8.1 years with a range from 1 to 60 years of age.

Etiology

Infection by roundworms, Toxocara canis or Toxocara cati. These nematodes live and mature in dog or cat intestine, respectively. As a mature adult the organism releases eggs which are passed in the stool. Contact with infected materials leads to human infection.

Risk Factors

Geophagia (deliberate consumption of earth, soil, or clay), young age, playing in sand boxes, exposure to and ownership of puppies and kittens (specifically young dogs and cats). In puppies 2 to 6 months old the prevalence of Toxocara canis has been reported to be over 80%. In dogs older than one year this number drops to 20%. Water or food such as produce contaminated with the toxocara eggs is another possible exposure.

Pathophysiology

The definitive host are cats and dogs. Ingestion with toxocara eggs leads to systemic and ocular infection. After ingestion the eggs matures into larvae and reaches systemic circulation via the gut. The larve can infect many organs including the heart, liver, brain, muscle, lungs, and the eyes. When it infects different tissues it is called VLM. Reactive inflammatory processes lead to the organism's encapsulation and the formation of eosinophilic granulomas. Ocular larva migrans is a result of the ingested egg developing and migrating to the eye causing local disease.

Primary Prevention

Avoidance of exposure to risk factors. By some studies, over 90% of patients have an identifiable history of exposure.

Diagnosis

History

The majority of patients will either own or have exposure to a dog or cat. Patients without this history likely were unknowingly in contact with contaminated surfaces or are reported as geophagic by their parents. The vast majority of patients report unilateral reduced vision as well as other symptoms typical of uveitis, such as photophobia. In approximately 10% of cases it is bilateral.

Physical examination

OLM is unilateral in 90% of cases. Ocular toxocariasis typically presents as posterior uveitis in 3 different subtypes

- Central posterior granuloma (25-46%) Acutely, Toxocara retinochoroiditis appears as a hazy, ill-defined white lesion with an overlying vitritis. As the inflammation resolves the lesion is seen as a distinct, well-demarcated, elevated white mass ranging from one-half to four disc diameters in size.

- Peripheral granuloma (20-40%).

- Chronic endophthalmitis (25%) - patient presents with dense vitreous inflammation mimicking endophthalmitis

Signs

The most common sign associated with ocular toxocariasis is vitritis as it is identified in over 90% of patient. Other presenting signs include leukocoria, ocular injection, and strabismus.

Symptoms

Decreased vision, pain, photophobia, and floaters.

Clinical diagnosis

Clinical diagnosis is based on history and examination as described in this article.

Laboratory test

Unlike in VLM, OLM patients do not typically have marked eosinophilia. The most useful test for ocular toxacariasis is an ELISA.

ELISA for Toxocara excretory secretory (TES) antigen has a 90% sensitivity and specificity of VLM. OLM is not as easily detectable in peripheral blood tests and so this test is supportive but not the gold standard of diagnosis in ocular presentations. Specificity is lowered due to cross reaction with other helminthic infections. In addition, the value of this test is compromised secondary to the high prevalence of seropositivity to Toxocara without symptomatic infection in the general population. In one study, ELISA was found positive in 50% of patients while negative in 36.4% of patients and unknown in 13.6% of patients (N=22). In particular, one patient in this study with a negative serum ELISA was later found to have a positive aqueous ELISA. In select cases the Elisa may be negative. Performing this test on aqueous or vitreous samples can prove to be diagnostic.

Differential diagnosis

- Retinoblastoma (in this case B scans typically find calcifications which are extremely uncommon in OLM. Noninflamed eyes without cataract are also suggestive of Retinoblastoma.)

- Coats Disease

- Persistent Fetal Vasculature

- Retinopathy of Prematurity

- Familial Exudative Vitreoretinopathy

- Idiopathic Peripheral Uveoretinitis

- Toxoplasmosis

- Histoplasmosis

- Optic Neuritis

Management

Management of this disease focuses on three main points:

- Minimizing inflammation

- Eliminating the offending organism

- Addressing vitreal and retinal complications secondary to infection

Medical therapy

Anti-inflammatory therapy

Topical steroids are typically used to limit inflammation in order to prevent the development of tractional membranes and resulting retinal detachments. Other options include periocular injections and oral corticosteroids at 0.5-1 mg/kg. In the case of anterior segment inflammation, cycloplegics are also used to prevent the formation of synechiae.

Anti-parasitic therapy

The use of these drugs is unproven in the case of ocular toxocariasis. There is some support for the use of albendazole or thiabendazole to eradicate the organism. Albendazole is the preference of some physicians as it has increased blood brain barrier penetration.

Medical follow up

There is no standard protocol for medical follow up specific to ocular toxocariasis. Patients are typically followed as those with other forms of uveitic disease.

Surgery

The CDC reports that 25% of patients presenting with new cases of ocular toxocariasis require surgery. Vitrectomy is the most common surgical therapy for ocular toxocariasis. The most common indications for surgical intervention are persistent vitreous opacification, hemorrhage, tractional retinal detachment, and epiretinal membranes. Other indications for retinal surgery include rhegmatogenous retinal detachments. Tractional retinal detachments are more common in cases that include granulomas located in the peripheral retina.

During surgery, it is important to just circumcise the membranes instead of delaminating or peeling them as they tend to me quite adherent. Even though excision of the granuloma has been reported, it is not widely recommended due to the possibility of disastrous complications. With modern vitreoretinal techniques the anatomical success is 83-100%. Preoperative visual acuity and presence of retinal fold across the macula can affect post operative visual outcome.

Other interventions include laser photocoagulation and cryotherapy to treat the larve and granuloma respectively.

Surgical follow up

There is no established protocol for surgical follow up of toxocariasis patients. In one study, 87% of patients requiring surgery had visual acuities worse than 20/400 with a mean age at the time of surgery being 8.1 years. This limited functional success was found despite each surgery being deemed an anatomical success with rare complications.

Sequelae

A list of sequelae of this disease more commonly includes cystoid macular edema, traction retinal detachment, epiretinal membranes, and cataract. With more infrequency OLM has also been associated with retrolenticular membrane, rhegmatogenous retinal detachment, anterior lens capsule membrane, and macular holes.

Prognosis

Prognosis is typically excellent for those patients without sequelae. These cases are mostly self limited or controlled with medical management. It has been noted that presenting visual acuity is most predictive of final visual acuity. A median visual acuity of 20/50 has been associated with patient presentations with posterior pole granulomas. Patients with peripheral granulomas had a median visual acuity of 20/70 and presentations with endophthalmitis were associated with a median visual acuity between 20/200 and 20/400.

Those that require surgical intervention typically have a poorer prognosis and visual acuity. In very rare cases ocular toxocara has been associated with no light perception vision. Potential complications that develop include cystoid macular edema and retinal detachment.

Additional Resources

- www.aao.org

- www.cdc.gov

- www.revophth.com

References

- Brown DH. "Ocular toxocara canis." J Pediatr Ophthalmol. 1970;7:182-91.

- CDC. "Ocular toxocariasis - United States, 2009-2010." MMWR. 2011;60:734-6. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6022a2.htm November 28, 2011.

- Good B, Holland CV, et al. "Ocular toxocariasis in school children."Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:173-8.

- Gillespie SH, Dinning WJ, et al. "The spectrum of ocular toxocariasis." Eye. 1993;7:415-8.

- Gioliari GP, Ramirez G, et al. "Surgical treatment of ocular toxocariasis: anatomic and functional results in 45 patients.Eur J Ophthalmol. 2011;21:490-4.

- Schneier AJ, Durand ML. "Ocular toxocariasis: advances in diagnosis and treatment." Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2011;51:135-44.

- Shields JA. "Ocular toxocariasis. A review." Surv Opthalmol. 1984;28:361-81.

- Stewart JM, Cubillan LDP, et al. "Prevalance, clincial features, and causes of vision loss along patients with ocular toxocariasis." Retina-J Ret Vit Dis. 2005;25:1005-13.