Diabetic Papillopathy

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Disease

Diabetic papillopathy or diabetic papillitis is a relatively rare ocular manifestation of diabetes mellitus. Diabetic papillopathy was first described in a series of teenage, type 1 diabetic patients in 1971 by Lubow and Makley,[1] but since that time has been reported in both type 1 and type 2 diabetic patients of all ages.[2][3][4][5] It is most often unilateral, however bilateral cases may occur. [6] Patients may report blurred vision, but many present with no symptoms at all.

Diabetic papillopathy causes optic disc edema with minimal visual changes, which distinguishes it from other optic neuropathies. Diabetic papillopathy remains a controversial topic as some authors believe that it is a form of non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (NAION), but this has yet to be determined.[7]

Etiology

This is a disease of the optic nerve typically associated with diabetes mellitus, possibly further exacerbated in patients who have had rapid correction of their blood glucose levels.

Risk Factors

Diabetic papillopathy is seen in type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus, and incidence is estimated at 0.5 percent.[2] There is no clear association between diabetic papillopathy, glycemic control, or stage of diabetic retinopathy.[2][5] It is believed, however, that rapid glycemic control is contributory to the development of diabetic papillopathy. It is imperative to always ask patients if any new changes were made to their diabetic regimen, specifically whether insulin had recently been started.[8] Other possible risk factors include optic disc drusen.[9] A study evaluating diabetic optic neuropathy (a collective term including neovascularization of disc, diabetic papillopathy, NAION, and optic atrophy) found duration of diabetes, older age, systolic blood pressure, severity of diabetic retinopathy, central foveal thickness, and glycated hemoglobin as its risk factors.[10]

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of diabetic papillopathy is not clearly understood. Diabetic papillopathy is presumed to result from diabetic microangiopathy, and this theory is supported by abnormal disc surface staining and fluorescein leakage found on fluorescein angiogram (FA).[2][11][12] However, there are no pathology studies reported to confirm this theory.

As previously mentioned, rapid glycemic control is thought to be associated with diabetic papillopathy. This rapid change may induce the accumulation of fluid within the cellular and interstitial spaces between the retinal nerve fibers, ultimately causing compression at the retrolaminar portion of the optic nerve.[8] This compression leads to decreased axoplasmic flow at the lamina cribrosa, leading to disc edema.[13]

Diagnosis

Physical Examination

Initial visual acuity may range from 20/20 to 20/200. RAPD (relative afferent pupillary defect) or dyschromatopsia are typically absent. Visual field deficits are rare, but, if present, tend to correlate with the extent of the edema of the nerve.

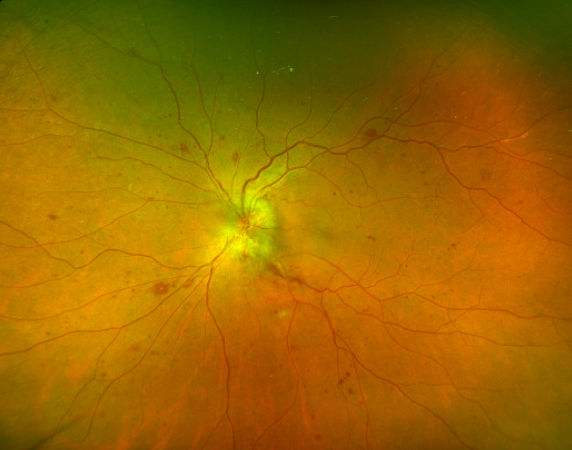

On fundoscopy, the optic nerve head is edematous and hyperemic. Dilated optic nerve head vasculature is seen in 50% of cases, and they typically remain on the disc surface and do not extend into the vitreous. This can be distinguished from neovascularization of the disc (NVD), as can be seen in diabetic retinopathy, in which vessels are oriented randomly throughout the vitreous and proliferate into it. [2]

Macular edema is frequently found in diabetic papillopathy, seen in more than 70% of patients. [11] Diabetic retinopathy is not present in all cases and has been reported in 63-80% of cases. [2] The absence of diabetic retinopathy does not rule out diabetic papillopathy as a cause for optic nerve head swelling.

Symptoms

Patients with diabetic papillopathy tend to be asymptomatic but may present with mild blurring of vision. [4] Interestingly, signs of optic neuropathy such as a relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD), dyschromatopsia, and visual field defects are typically not seen [11].

Clinical Diagnosis

Diabetic papillopathy is a diagnosis of exclusion in diabetic patients with minimal visual loss, optic disc edema, no signs of increased intracranial pressure, and no other associated symptoms of inflammatory optic neuropathies. Patients presenting with unilateral or bilateral disc edema with clinical features consistent with diabetic papillopathy should be evaluated with visual field testing and fluorescein angiography to exclude other causes of optic disc edema.

Additional diagnostic testing is required in patients with bilateral papilledema to exclude potentially life-threatening causes, such as intracranial masses. Magnetic resonance imaging and lumbar puncture should be performed to further evaluate the patient.

Diagnostic procedures

Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT)

OCT of the optic nerve typically shows increased thickness of the papillary profile without loss of the retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL). [8] OCT macula can often be unremarkable, though edema from the nerve may track towards the macula.

Fluorescein angiography (FA)

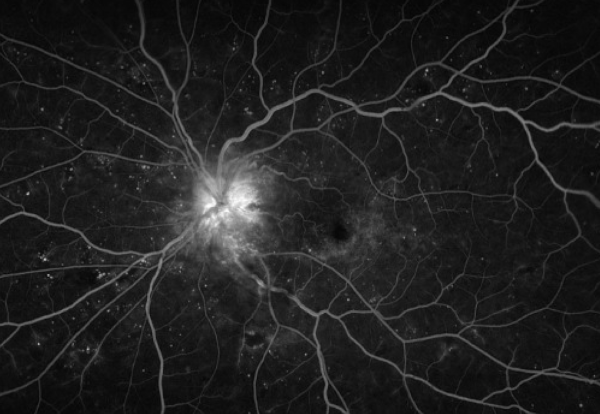

FA is useful in distinguishing diabetic papillopathy from other etiologies, such as neovascularization of the disc (NVD) and NAION. Diabetic papillopathy may present with prominent disc telangiectasias and associated disc edema, which can be easily confused for NVD. However, diabetic papillopathy usually demonstrates disc and peripapillary leakage with radial distribution of fluorescein in dilated vessels versus the random pattern of vasculature with intravitreal leakage in NVD.[14]

In cases without prominent telangiectasia, the delayed filling pattern of the disc can mimic that seen in NAION. In this case, it is important to correlate this with optic nerve dysfunction, which is seen in NAION rather than diabetic papillopathy. [14]

Visual field testing

Visual field examination may show blind spot enlargement in patients with diffuse disc edema, but most will show no significant visual field defect. [2][5][11][15]

Differential diagnosis

As diabetic papillopathy is a diagnosis of exclusion, it is important to discuss the differential diagnosis and tests required to rule out other possible diagnoses. The following is a brief discussion of other diagnoses that present with optic nerve head swelling.

The differential includes:

- Non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (NAION)

- Arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (AAION)

- Optic neuritis and other inflammatory optic neuropathy

- Compressive optic neuropathy (e.g., orbital tumors)

- Infiltrative optic neuropathy

- Neuroretinitis

- Papilledema

Management

General treatment

There are no well-studied treatments for diabetic papillopathy. Although it is not proven that diabetic microangiopathy is the etiology of disc edema, a few studies looked at the effectiveness of different treatment modalities based on this theory. Observation is a reasonable initial approach as these patients can improve without intervention (assuming life-threatening causes for disc edema have been excluded).

Corticosteroids

There are a few studies that reported the favorable outcome of a periocular steroid injection (including subtenon triamcinolone) in diabetic papillopathy. An observational study by Mansour et al. looked at 5 diabetic patients who received periocular steroid treatment for severe symptomatic diabetic papillopathy. [16] This study found that the duration of diabetic papillopathy was shortened from a median of 5 months to 3 weeks, and rapid visual recovery was seen.

Another study looked at the effect of oral corticosteroids in preventing the progression of diabetic papillopathy to NAION. An observational cohort study done by Hayreh et al. showed that there is no significant difference in the incidence of progression between patients who received steroid treatment and patients who did not. [17]

Intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (Anti-VEGF) agents

Several case reports described the use of intravitreal anti-VEGF with improvement in vision, however no prospective studies have been undertaken to see if this varies the course of disease. [18][19][20][21] Larger clinical studies are needed to prove the efficacy and safety of anti-VEGF agents.

Prognosis

Diabetic papillopathy is generally known to have a good visual prognosis.

One study reported that approximately 92% of eyes had no changes in visual acuity after disc swelling resolved, and 75% of the eyes had visual acuity better than 20/40 at the last visit. In this study, optic disc edema spontaneously resolved in roughly 4-9 months. [2]

However, there are some reported cases of vision loss in diabetic papillopathy, possibly due to worsening diabetic retinopathy, development of disc neovascularization, or progression to NAION. In one study, 36% of the eyes progressed to NAION with a mean duration of 16.8 weeks. [15] Although diabetic papillopathy is known to run a benign course, regular testing should be done to evaluate for changes and the possibility of progression.

References

- ↑ Lubow M, Makley TA Jr. Pseudopapilledema of juvenile diabetes mellitus. Arch Ophthalmol 1971;85:417–422.

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 Bayraktar Z, Alacali N, Bayraktar S. Diabetic papillopathy in type II diabetic patients. Retina 2002; 22:752.

- ↑ Appen RE, Chandra SR, Klein R, Myers FL. Diabetic papillopathy. Am J Ophthalmol 1980;90:203–209.

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 Pavan PR, Aiello LM, Wafai MZ, Briones JC, Sebestyen JG, Bradburry MJ. Optic disc edema in juvenile-onset diabetes.Arch Ophthalmol 1980;98:2193–2195.

- ↑ Jump up to: 5.0 5.1 5.2 Barr CC, Glaser JS, Blankenship G: Acute disc swelling in juvenile diabetes. Clinical profile and natural history of 12 cases. Arch Ophthalmol 98: 2185–92, 1980

- ↑ Beri M, Klugman MR, Kohler JA, Hayreh SS. Anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. VII. Incidence of bilaterality and various influencing factors. Ophthalmology. 1987 Aug;94(8):1020-8.

- ↑ Hayreh SS. Diabetic papillopathy and nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. Surv Ophthalmol 2002; 47:600.

- ↑ Jump up to: 8.0 8.1 8.2 Mafrici, Marco, et al. “Bilateral Diabetic Papillopathy Developed after Starting Insulin Treatment. Potential Toxic Effect of Insulin? A Case Report.” European Journal of Ophthalmology, 2020, p. 112067212098438.

- ↑ Becker D, Larsen M, Lund-Andersen H, Hamann S. Diabetic papillopathy in patients with optic disc drusen: Description of two different phenotypes [published online ahead of print, 2022 May 15]. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2022;11206721221100901. doi:10.1177/11206721221100901

- ↑ Hua R, Qu L, Ma B, Yang P, Sun H, Liu L. Diabetic Optic Neuropathy and Its Risk Factors in Chinese Patients With Diabetic Retinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2019;60(10):3514-3519. doi:10.1167/iovs.19-26825

- ↑ Jump up to: 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Regillo CD, Brown GC, Savino PJ, et al. Diabetic papillopathy. Patient characteristics and fundus findings. Arch Ophthalmol 1995; 113:889.

- ↑ Brancato R, Menchini U, Bandello FM. Diabetic papillopathy: fluorangiographic aspects. Metab Pediatr Syst Ophthalmol 1986;9:57–61.

- ↑ Kline, Lanning B. “Chapter 9 - The Swollen Optic Disc.” Neuro-Ophthalmology Review Manual, Slack Incorporated, New York, NY, 2008, pp. 139–140

- ↑ Jump up to: 14.0 14.1 Vaphiades MS. The disk edema dilemma. Surv Ophthalmol 2002; 47:183.

- ↑ Jump up to: 15.0 15.1 Almog Y, Goldstein M. Visual outcome in eyes with asymptomatic optic disc edema. J Neuroophthalmol 2003; 23:204.

- ↑ Mansour AM, El-Dairi MA, Shehab MA, et al. Periocular corticosteroids in diabetic papillopathy. Eye (Lond) 2005; 19:45.

- ↑ Hayreh SS, Zimmerman MB.Incipient nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. Ophthalmology. 2007 Sep;114(9):1763-72. Epub 2007 Mar 27.

- ↑ Yildirim M, Kilic D, Dursun ME, Dursun B. Diabetic papillopathy treated with intravitreal ranibizumab. Int Med Case Rep J. 2017;10:99. Epub 2017 Mar 22.

- ↑ Kim M, Lee JH, Lee SJ. Diabetic papillopathy with macular edema treated with intravitreal ranibizumab. Clin Ophthalmol 2013; 7:2257

- ↑ Al-Hinai AS, Al-Abri MS, Al-Hajri RH. Diabetic papillopathy with macular edema treated with intravitreal bevacizumab. Oman J Ophthalmol 2011; 4:135

- ↑ Al-Dhibi H, Khan AO. Response of diabetic papillopathy to intravitreal bevacizumab. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol 2011; 18:243