Neurosarcoidosis

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Neurosarcoidosis

Disease

Sarcoidosis is a chronic, inflammatory disorder characterized pathologically by non-caseating granulomas affecting one or multiple organs. The most commonly affected organs include the lungs, skin, and the eye[1]. When sarcoidosis affects the central nervous system (CNS) and/or peripheral nervous system (PNS), it is termed “neurosarcoidosis”[2] Neurosarcoidosis can appear with other forms of sarcoidosis (e.g., cutaneous, pulmonary, cardiac, or renal sarcoidosis) but it can also remain isolated [3].

Epidemiology

Sarcoidosis occurs more frequently in Northern Europe, Japan, and the central United States[3]. In the U.S. it occurs more often in African-American females and is usually more severe in this population as well, having a higher likelihood of multi-organ involvement, chronicity, and mortality[4] In the United States, the incidence ranges from 11 per 100,000 in Caucasians to 36 per 100,000 in African-Americans[4]while the prevalence is approximately 152 - 215 per 100,000.[5]. Sarcoidosis is seen most commonly in patients in their 3rd-5th decades of life but it can affect patients of any age including children[4] [6]. Approximately 5-10% of patients with sarcoidosis will have neurological involvement [5]but some research found evidence of neurosarcoidosis in up to 25% of cases of sarcoidosis on autopsy[3][7],indicating that it is can be occult and asymptomatic. Neurosarcoidosis affecting the peripheral nervous system is more commonly seen in Caucasians than in African-Americans[7].

Etiology

The etiology of neurosarcoidosis remains unknown. The formation of non-caseating granulomas is thought to be due to an abnormal immune response where stimulated Th1 cells release IL-2 and IFN-gamma[5] resulting in excessive activity of macrophages and T-cells due to prolonged exposure of antigenic stimuli[8] . The precise inciting antigen and pathophysiology of neurosarcoidosis however remains ill defined.

Risk Factors

Certain exogenous factors are thought to play a role in the development of neurosarcoidosis such as agricultural employment, insecticides, and work environments with mold exposures[8]. There also seems to be a genetic component since sarcoidosis is more often seen in the African-American population. Furthermore, certain genetic mutations may increase susceptibility to the disease, including the gene butyrophilin-like 2 (BTNL2), which is thought to be involved in T-lymphocyte regulation and activation[8].

General Pathology

The histological examination of the non-caseating granulomas of neurosarcoidosis resembles that of sarcoidosis found in other organs. They consist of epithelioid cells and multinucleated giant cells surrounded by lymphocytes, plasma cells, and mast cells[9] and a center central coagulative necrosis that appears "cheese-like" due to many dead cells with proteinaceous material.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of sarcoidosis is not fully understood. It is thought to be related to chronically stimulated Th1 cells that secrete factors that recruit and activate macrophages, which in turn secrete cytokines and to recruit other cells and result in the formation of granulomas[9].

Diagnosis

Neurosarcoidosis should be considered in patients who have a history of systemic sarcoidosis (usually in 2 or more organs) and present with neurological findings. It is important to know however, that Neurosarcoidosis (specially ocular) can appear even when there is no systemic, or Pulmonary Sarcoidosis, reason why it is part of "Extrapulmonary Sarcoidosis". A study by Ramos-Casals, et al. showed a prevalence of CNS involvement over PNS involvement and a clear differentiation between the systematic phenotypes of each subset. CNS subset was associated with less thoracic and greater concomitant ocular and glandular involvement while PNS subset was associated with greater concomitant liver and spleen involvement[10].

Zajicek et al [11] have proposed the following criteria for diagnosing neurosarcoidosis:

Definite: A clinical presentation that suggests neurosarcoidosis while other possible medical conditions are excluded and the positive histological presence of non-caseating granuloma from a biopsy of the central nervous system that is affected.

Probable: A clinical presentation that suggests neurosarcoidosis with laboratory support for CNS inflammation (CSF with elevated protein and/or cells, oligoclonal bands, and/or MRI evidence that suggests neurosarcoidosis) and exclusion of other possible alternative diagnoses with evidence for systemic sarcoidosis determined either through histology or at least two indirect tests including gallium scan, chest X-ray, or serum angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE).

Possible: A clinical presentation that suggests neurosarcoidosis with alternative diagnoses being excluded.

During the first International Workshop on Ocular Sarcoidosis (IWOS), suggestive clinical signs, laboratory values, and diagnostic criteria for ocular sarcoidosis were established[12].

While the IWOS criteria had shown high reliability in the diagnosis of ocular sarcoidosis[13], limitations included low diagnostic value of liver enzyme testing, inapplicable conditions for negative TB testing in BCG vaccinated patients, need for more investigative studies, and low sensitivity of the “possible OS” category.

Revised criteria addressing these limitations were established at the IWOS conference in 2017 and are as follows[14]:

Criteria for the diagnosis of ocular sarcoidosis established by IWOS:

Definite: Biopsy-supported diagnosis with a compatible uveitis.

Presumed: No biopsy performed, but chest x-ray or CT scan revealing the presence of bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy with a compatible uveitis.

Probable: No biopsy performed and no imaging revealing bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy, but 3 suggestive intraocular signs and 2 supportive investigations present.

Possible: Negative lung biopsy, but at least 4 suggestive intraocular signs and at least 2 positive laboratory results.

Signs suggestive of ocular sarcoidosis established during IWOS: In some intraocular inflammation cases no significant granulolmas are seen making the diagnosis of "sarcoid" related uveitis very challenging.

1. Mutton-fat/granulomatous keratic precipitates and/or iris nodules (Koeppe/Busacca)

2. Trabecular meshwork nodules and/or tent-shaped peripheral anterior synechiae

3. Snowballs/string of pearls vitreous opacities

4. Multiple chorioretinal peripheral lesions (active and/or atrophic)

5. Nodular and/or segmental periphlebitis (with or without candlewax drippings) and/or retinal macroaneurysm in an inflamed eye

6. Optic disc nodule(s)/granuloma(s) and/or solitary choroidal nodule

7. Bilaterality

The Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) [15] which include machine learning process for clinical research purposes from an international collaboration group was used and proven to have sufficient concordance in classification rate to be used for translational research.[16][17] In brief, the Classification Criteria for Sarcoid Uveitis includes:

1. Compatible uveitic picture,

- Anterior uveitis

- Intermediate or Anterior/intermediate uveitis

- Posterior uveitis with either choroiditis (paucifocal choroidal nodule[s] or multifocal choroiditis)

- Panuveitis with choroiditis or retinal vascular sheathing or retinal vascular occlusion

2. Evidence of sarcoidosis

- Tissue biopsy demonstrating non-caseating granulomata

- Bilateral hilar adenopathy on chest imaging

Exclusions

1. Positive serology for syphilis using a treponemal test

2. Evidence of infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis

- Histologically- or Microbiologically-confirmed infection with M. tuberculosis

- Positive interferon-Ɣ release assay (IGRA)

- Positive tuberculin skin test

Laboratory values suggesting ocular sarcoidosis established by IWOS:

1. Negative tuberculin test in a BCG-vaccinated patient or in a patient with a previously positive tuberculin skin test

2. Elevated serum angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) and/or elevated serum lysozyme

3. Positive chest x-ray, showing bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy

4. Abnormal liver enzyme tests

5. Positive chest CT scan in patients with a negative chest x-ray

Differential Diagnosis

Tuberculosis should be considered as it can similarly involve the nervous system with granulomas. Therefore, it is important to consider tuberculosis in patients who have had previous exposure to tuberculosis or who are from areas where tuberculosis is endemic. Certain neoplastic diseases (e.g., EBV associated lymphomatoid granulomatosis) can mimic sarcoidosis or be associated with sarcoid like reactions[7]. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (formerly Wegener granulomatosis) and other necrotizing and non-necrotizing inflammatory granulomatous vasculitides should also be considered in the differential diagnosis of sarcoid [7]. Multiple sclerosis (MS) may also be difficult to differentiate from neurosarcoidosis clinically without a biopsy but typically other clinical and radiographic features are present that can differentiate MS from the MS mimic, neurosarcoidosis[18]

Additionally, Neurosarcoidosis can mimic multiple entities, such as vasculitis (such as Giant Cell Arteritis), meningioma[19], occipital mass[20], optic glioma[21], among others.

History

The majority of cases of ocular and neurosarcoidosis occur concomitantly with systemic sarcoidosis however both can occur in isolation and therefore, it is important to learn about the other symptoms suggestive of systemic sarcoidosis (e.g., cutaneous or pulmonary disease). Given that other disease processes can present with similar symptoms (e.g., tuberculosis) it is important to learn about risk factors and other symptoms that may indicate infectious or inflammatory diseases other than neurosarcoidosis.

Physical examination

The physical exam findings can vary significantly depending upon which areas of the nervous system are affected. Cranial neuropathies are often affected by neurosarcoidosis, with the optic (II) and facial (VII) nerves being most commonly involved[18][11] Consequently, physical exam findings suggesting cranial nerve deficits may be suggestive of neurosarcoidosis. Large granulomatous lesions in the brain may result in mass-effect like symptoms that can be present on physical exam, such as hemiparesis, and sensory deficits. Hydrocephalus can occur, typically non-communicating type, and it is associated with a very poor prognosis. If there is involvement in the spinal cord, then corresponding symptoms can result depending upon the areas of the spinal cord affected. Similarly, when the peripheral nerves are affected, physical exam findings such as weakness and sensory deficits may be found.

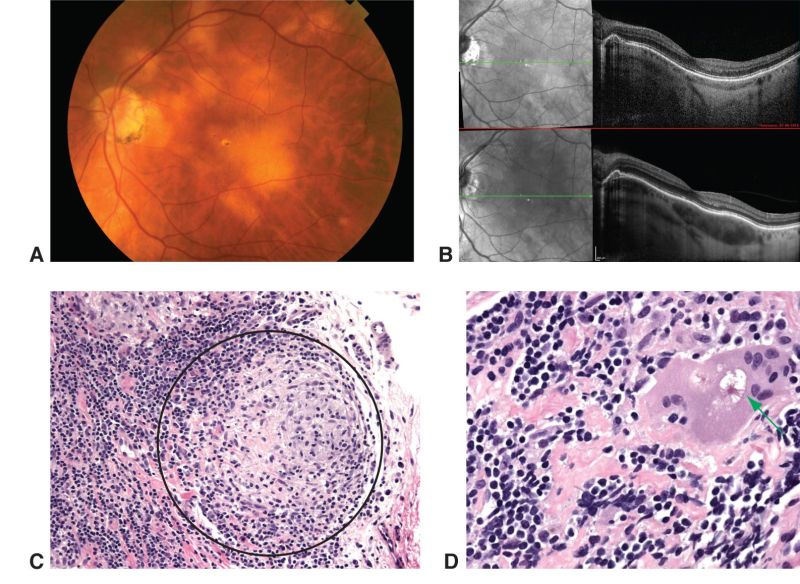

As per criteria above, Suggestive findings for ocular sarcoidosis include mutton-fat keratic precipitates, iris nodules, snow balls in vitreous cavity, multiple chorioretinal peripheral lesions, retinal periphlebitis and bilateral involvement. Additionally, enhanced depth imaging using optical coherence tomography has aided in differentiating types of uveitis and characterizing choroidal granulomas[13].

Symptoms

Symptoms of neurosarcoidosis can vary greatly depending upon the area of the nervous system affected. It more commonly presents with systemic involvement rather than isolated.

Nonspecific[7]

- Fatigue

- Headache

- Cognitive dysfunction

- Confusion

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Mood disorders

- Fever

Cranial neuropathies[18]

- Facial nerve MOST common +/- swelling of the parotid gland[7]

- Optic nerves

It is important to note that any of the cranial nerves can be affected and result in their corresponding deficits..

NeuroOphthalmic/Orbital[7]

- Anterior or posterior uveitis

- Central or peripheral vision loss

- Ptosis

- Eye pain

- Proptosis

- Diplopia

- Dry eyes (impaired neural reflex arc and lacrimal gland system.[22])

Neurologic

- Meningitis with symptoms of nuchal rigidity and headache[23]

- Seizures

- Hemiparesis (if mass effect)

- Ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke (if brain vessels affected)[24]

- Parkinsonian-like symptoms (if basal ganglia involved)

- Spinal cord involvement = paresthesias, weakness, bladder and bowel incontinence, and erectile dysfunction[7][25].

- Guillan-Barré-like syndrome[7]

- Weakness and numbness (if peripheral nerves affected)

Endocrinologic

- Hypothalamus

- Pituitary abnormalities or Panhypopituitarism. Pituitary gland involvement in 10-15% of patients= Diabetes insipidus, hyperprolactinemia, gonadotropin deficiency, and TSH deficiency [7] [18].

Diagnostic Procedures/Laboratory Tests

Since neurosarcoidosis most commonly occurs concomitantly with systemic sarcoidosis, there are a number of serum biomarkers and imaging results that may be abnormal, such as serum ACE, lysozyme, calcium, ESR and/or chest X-ray. These tests are helpful in the diagnosis of systemic sarcoidosis, however they lack sufficient specificity in the diagnosis of neurosarcoidosis and are therefore limited in their utility[26]. More specific laboratory tests include those that indicate CNS inflammation, such as CSF with elevated IgG, mild to moderate lymphocytosis, reduced glucose or MRI evidence suggesting neurosarcoidosis. In some cases, direct involvement of CNS may present with normal brain imaging and abnormal CSF studies. In a study within the Centre for Neurosarcoidosis, from 166 patients with biopsy-proven highly probable sarcoidosis of the CNS, 70% of the cases displayed active CSF even when imaging was normal, oligoclonal bands were seen in 30% of cases and unmatched bands were only seen cases with isolated neural involvement[27].

When intraocular inflammation related to Sarcoidosis, recent lab studies have shown elevated soluble interleukin 2 receptor and lymphopenia have shown to be effective markers for uveitis associated with sarcoidosis[13].

Many imaging modalities may be useful in the evaluation of neurosarcoidosis, including HRCT, MRI, and/or FDG-PET. MRI is considered the most sensitive, but it is non-specific in the assessment of neurosarcoidosis[23]. The most common MRI findings include leptomeningeal involvement which may reveal diffuse or thickening with gadolinium enhancement. According to the Zajicek criteria, excluding other possible diagnoses, and a biopsy from the CNS or peripheral nerves demonstrating non-caseating granulomas is essential for the diagnosis of definitive neurosarcoidosis[11]. Other new PET strategies have been explored that are not FDG dependent such as: somatostatin receptors imaging, C-X-C motif chemokine receptor (CXCR4- activated macrophages expression)[28]

A chest CT scan can confirm the findings of pulmonary sarcoidosis (hilar adenopathy) , however Normal CT chest can not rule out sarcoidosis, specially in white patients.[29]

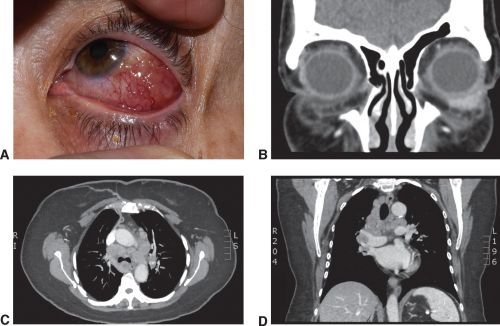

Histopathological confirmation of sarcoidosis (Image 1) is the Gold Standard.

Management

General treatment

The severity of symptoms must be evaluated in determining whether or not treatment is necessary[1] Treatment for neurosarcoidosis is primarily pharmacological. Although in certain cases, surgical options may be necessary. Radiotherapy has also shown some benefit in patients who are treatment refractory to more traditional modalities.

Medical therapy

Oral corticosteroids are considered first-line management, and acute relapse management, for patients with symptomatic neurosarcoidosis with intravenous corticosteroids being reserved for a more severe presentation that is refractory to oral steroids[23]. It is important to note that neurosarcoidosis is considered to be less responsive to corticosteroids compared to sarcoidosis affecting other organs, and patients with neurosarcoidosis have a higher chance of relapse[18]. Second-line medications include methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, and azathioprine[30], and these are often utilized in patients who are refractory to corticosteroids; these medications combined with corticosteroids have also been shown to be favorable in patients with severe symptoms[31]. Other additional treatment include infliximab and adalimumab(TNF inhibitors)[32], leflunomide[33], tocilizumab(IL-6 receptor inhibitor), tofacitinib and baricitinib (JAK inhibitors previously used forv refractory cutaneous sarcoidosis and multiorgan system sarcoidosis respectively)

The selection of treatment should be customized to patient. The effect of treatment should be monitored considering that medications such as azathioprine, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil have a slow-onset action on full immunosuppression, therefore concomitant use of steroids is recommended. Furthermore, treatment of conditions that result secondary to neurosarcoidosis is often necessary, such as antiepileptics for patients who develop seizures.

Surgery

Surgery for neurosarcoidosis is usually not indicated unless life-threatening complications result, such as mass-occupying lesions resulting in hydrocephalus, increased intracranial pressure, and/or spinal cord compression[34]. Most surgery in sarcoidosis is confined to diagnostic biopsy for histological confirmation of disease.

Prognosis

The prognosis of patients with neurosarcoidosis varies widely and depends upon severity and location in the nervous system. Although sarcoid uveitis often responds well to treatment, optic nerve involvement may produce permanent visual loss[35]. Similarly, patients with involvement of the spinal cord often have a worse prognosis[18]. In the case of the neurosarcoidosis affecting neuroendocrine structures in the brain, the neuronal damage is often irreversible, and these patients usually require life-long hormonal replacement therapy[36]. Nevertheless, when neurosarcoidosis is treated early with aggressive therapy, the outcomes are often favorable.

Additional Resources

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Iannuzzi MC, Fontana Jr. Sarcoidosis: clinical presentation, immunopathogenesis, and therapeutics. JAMA. 2011;305:391-9.

- ↑ Lacomis D. Neurosarcoidosis. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2011;9(3):429-36.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Hebel R, Dubaniewicz M, et al. Overview of neurosarcoidosis: recent advances. J Neurol. 2015;262(2):258-67.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Rybicki BA, Iannuzzi MC. Epidemiology of sarcoidosis: recent advances and future prospects. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;28:22-35

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Pirau L, Lui F. Neurosarcoidosis. [Updated 2023 Jul 3]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534768/

- ↑ Koné-Paut I, Portas M, et al. The pitfall of silent neurosarcoidosis. Pediatr Neurol. 1999;20:215-18.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 7.8 7.9 Tana C, Wegener S, et al. Challenges in the diagnosis and treatment of neurosarcoidosis. Ann med. 2015;47(7):576-91.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Tana C, Giamberardino M, et al. Immunopathogenesis of sarcoidosis and risk of malignancy: a lost truth? Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2013;26(2):305-13.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Segal B. Neurosarcoidosis: diagnostic approaches and therapeutic strategies. Curr Opin Nuerol. 2013;26(3):307-13.

- ↑ Ramos-Casals M, Pérez-Alvarez R, Kostov B, et al. Clinical characterization and outcomes of 85 patients with neurosarcoidosis. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):13735. Published 2021 Jul 2.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Zajicek J, Scolding N, et al. Central nervous system sarcoidosis—diagnosis and management. Q J Med. 1999;92:103-117.

- ↑ Herbort, C. P., Rao, N. A., Mochizuki, M., & members of Scientific Committee of First International Workshop on Ocular Sarcoidosis (2009). International criteria for the diagnosis of ocular sarcoidosis: results of the first International Workshop On Ocular Sarcoidosis (IWOS). Ocular immunology and inflammation, 17(3), 160–169.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Yang, S. J., Salek, S., & Rosenbaum, J. T. (2017). Ocular sarcoidosis: new diagnostic modalities and treatment. Current opinion in pulmonary medicine, 23(5), 458–467.

- ↑ Mochizuki M, Smith JR, Takase H for the International Workshop on Ocular Sarcoidosis Study Group, et al Revised criteria of International Workshop on Ocular Sarcoidosis (IWOS) for the diagnosis of ocular sarcoidosis British Journal of Ophthalmology 2019;103:1418-1422.

- ↑ Trusko B, Thorne J, Jabs D, Belfort R, Dick A, Gangaputra S, Nussenblatt R, Okada A, Rosenbaum J; Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Project. The Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Project. Development of a clinical evidence base utilizing informatics tools and techniques. Methods Inf Med. 2013;52(3):259-65, S1-6. doi: 10.3414/ME12-01-0063. Epub 2013 Feb 8. PMID: 23392263; PMCID: PMC8728398.

- ↑ Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Working Group. Classification Criteria for Sarcoidosis-Associated Uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2021 Aug;228:220-230. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2021.03.047. Epub 2021 May 11. PMID: 33845001; PMCID: PMC8594768.

- ↑ Zur Bonsen LS, Pohlmann D, Rübsam A, Pleyer U. Findings and Graduation of Sarcoidosis-Related Uveitis: A Single-Center Study. Cells. 2021 Dec 29;11(1):89. doi: 10.3390/cells11010089. PMID: 35011651; PMCID: PMC8750073.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 18.5 Nozaki K, Judson M. Neurosarcoidosis. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2013;15(4):492-504.

- ↑ Solyman, Omar M. MD; Vizcaino, Maria Adelita MD; Fu, Roxana MD; Henderson, Amanda D. MD Neurosarcoidosis Masquerading as Giant Cell Arteritis With Incidental Meningioma, Journal of Neuro-Ophthalmology: March 2021 - Volume 41 - Issue 1 - p e122-e124 doi: 10.1097/WNO.0000000000000967

- ↑ Givre, Syndee J. M.D., Ph.D.; Mindel, Joel S. M.D., Ph.D. Presumed Bilateral Occipital Neurosarcoidosis A Case Report, Journal of Neuro-Ophthalmology: March 1998 - Volume 18 - Issue 1 - p 32-35

- ↑ Pollock, Jeffrey M MD; Greiner, Francis G MD; Crowder, Jason B MD; Crowder, Jessica W MD; Quindlen, Eugene MD Neurosarcoidosis Mimicking a Malignant Optic Glioma, Journal of Neuro-Ophthalmology: September 2008 - Volume 28 - Issue 3 - p 214-216 doi:10.1097/WNO.0b013e3181772a36

- ↑ Aoki T, Yokoi N, Nagata K, Deguchi H, Sekiyama Y, Sotozono C. Investigation of the relationship between ocular sarcoidosis and dry eye. Sci Rep. 2022 Mar 2;12(1):3469. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-07435-6. PMID: 35236907; PMCID: PMC8891351.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Terushkin V, Stern B, et al. Neurosarcoidosis: presentations and management. 2010;16(1):2-15.

- ↑ O’Dwyer J, Al-Moyeed B, et al. Neurosarcoidosis-related intracranial haemorrhage: three new cases and a systematic review of the literature. Eur J Neurol. 2013;20(1):71-8.

- ↑ Kaiboriboon K, Olsen T, et al. Cauda equina and conus medullaris syndrome in sarcoidosis. Neurologist. 2005;11(3):179-83.

- ↑ Marangoni S, Argentiero V, et al. Neurosarcoidosis: Clinical description of 7 cases with a proposal for a new diagnostic strategy. J Neurol. 2006;253:488-495.

- ↑ Kidd DP. Sarcoidosis of the central nervous system: clinical features, imaging, and CSF results. J Neurol. 2018;265(8):1906-1915.

- ↑ Voortman, Mareyea,b,c; Drent, Marjoleina,c,d; Baughman, Robert P.e Management of neurosarcoidosis: a clinical challenge, Current Opinion in Neurology: June 2019 - Volume 32 - Issue 3 - p 475-483 doi: 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000684

- ↑ Henderson, Amanda D. MD; Tian, Jing MS; Carey, Andrew R. MD Neuro-Ophthalmic Manifestations of Sarcoidosis, Journal of Neuro-Ophthalmology: October 26, 2020 - Volume Publish Ahead of Print - Issue - doi: 10.1097/WNO.0000000000001108

- ↑ Michael J. Bradshaw, Siddharama Pawate, Laura L. Koth, Tracey A. Cho, Jeffrey M. GelfandNeurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm Nov 2021, 8 (6) e1084; DOI: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000001084

- ↑ Scott T, Yandora K, et al. Aggressive therapy for neurosarcoidosis: long-term follow-up of 48 treated patients. Arch Neurol. 2007;64(5):691-6.

- ↑ Frohman, L. P. (2015)Treatment of Neuro-Ophthalmic Sarcoidosis. Journal of Neuro-Ophthalmology, 35 (1), 65-72. doi: 10.1097/WNO.0000000000000170

- ↑ Baughman RP, Lower EE. Leflunomide for chronic sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2004;21(1):43-48. doi:10.1007/s11083-004-5178-y

- ↑ Sharma O. Neurosarcoidosis: a personal perspective based on the study of 37 patients. Chest. 1997;112(1):220-8.

- ↑ Joseph F, Scolding N. Neurosarcoidosis: a study of 30 new cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80(3):297-304.

- ↑ Langrand C, Bihan H, et al. Hypothalmo-pituitary sarcoidosis: a multicenter study of 24 patients. 2012;105(10):981-95.