All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Acute retinal necrosis (ARN) is an inflammatory condition which may present as panuveitis. The principal causative viral agents have been found to be Varicella Zoster Virus (VZV) as well as Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV-1 and HSV-2) via polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing of intraocular fluid.

Disease Entity

History

In 1971, Urayama and colleagues[1] of Tohoku University in Japan reported 6 cases of a syndrome characterized by unilateral panuveitis, characterized by vitritis, acute necrotizing retinitis, retinal arteritis, and associated with rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. Young and Bird proposed the name of bilateral acute retinal necrosis.[2] In Japan, the name 'Kirisawa-type uveitis' had been used for ARN.

Etiology

ARN is caused by a viral infection due to VZV, most commonly, or HSV, less commonly. Older patients present more commonly with VZV or HSV-1 infections while younger patients present with HSV-2 infections. ARN has also been reported to be associated with cytomegalovirus (CMV) and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), but there is limited evidence to suggest these viruses cause ARN.

Risk factors

Genetics are believed to play a role in an individual’s risk for ARN with antigen expression of:

HLA-DQw7, HLA-Bw62, and HLA-DR4 in American Caucasian populations and

HLA-Aw33, HLA-B44, and HLA-DRw6 in Japanese populations.

Although ARN is most commonly seen in healthy, immunocompetent individuals, immunosuppression from corticosteroids, for example, may predispose patients. Immunocompromised patients, such as those with HIV, may develop progressive outer retinal necrosis (PORN), a more aggressive viral retinitis also caused by the Herpes family viruses. ARN may be seen in AIDS patients also. It has been reported in immediate post-partum period as well.

Previous history of herpetic infection including encephalitis may be present.

Epidemiology

This clinical entity is uncommon in the pediatric population. Most often it affects healthy, immunocompetent adults in their fifth to seventh decade. A clear racial or gender predilection has not been consistently demonstrated.

General pathology

There appear to be two distinct disease phases:

- Acute Herpetic Phase: episcleritis or scleritis, anterior (usually granulomatous) uveitis, vitreous opacification, and inflammation of the retina, retinal arterioles, and choroidal vasculature. Optic neuropathy can also occur.

- Late Cicatricial Phase: Retinal holes and tears most commonly occur at the junction of normal and atrophic/necrotic retina, leading to retinal detachment in 50-75% of untreated eyes. Subsequent proliferative vitreoretinopathy with retinal fibrosis and traction also contribute to retinal detachment. Multiple retinal holes with the appearance of a sieve are typical.

Pathophysiology

- Acute Herpetic Phase: Viral particles in the retina and vitreous provoke an intense inflammatory response. Retinal opacification is due to infiltration of the retina by viral particles and mononuclear cells. Lymphocytes and plasma cells, which produce antibodies to the provocative viral agent, likewise permeate the vitreous. Additionally, characteristic inflammation of the retinal arterioles occurs, resulting in vaso-occlusion and rapid necrosis of dependent, downstream retinal tissue. Choroidal vasculature may also be beset by similar inflammatory changes. An animal model of ARN suggests that involvement in the contralateral eye occurs via retrograde axonal transport to the hypothalamus and the contralateral retina.

- Late Cicatricial Phase: Organizational changes in the vitreous are thought to be the result of previous cellular infiltration during the acute phase. Contractile membranes may form in the vitreous and on the surface of the thinned, necrotic retina. Approximately 50 - 75% of patients will develop retinal detachments in the affected eye after ARN; the majority of retinal detachments occur within 3 months of the onset of ARN.

Diagnosis

History

The diagnosis of ARN, prior to the advent of PCR, was originally made based on clinical criteria and the use of electron microscopy to identify viral particles in retinal tissue of enucleated eyes.

Signs and symptoms

Patients with ARN typically present with acute onset of vision loss in one eye, which may be associated with redness, photophobia, pain, floaters, and flashes. Two-thirds of cases present with unilateral involvement. The remaining third of cases present with bilateral ARN (BARN).

Physical examination

Anterior segment involvement may include episcleritis, scleritis, corneal edema, keratic precipitates, and anterior chamber inflammation. Classically, posterior segment involvement includes vitritis, retinal vascular arteriolitis, and peripheral retinitis. Retinitis typically begins as multifocal areas of retinal whitening and opacification, oftentimes with scalloped edges. Initially, this patchy retinitis usually starts peripherally and, then progresses to become increasingly confluent while advancing more posteriorly.[3] Retinal hemorrhages due to occlusive vasculitis may be seen.

Clinical diagnosis

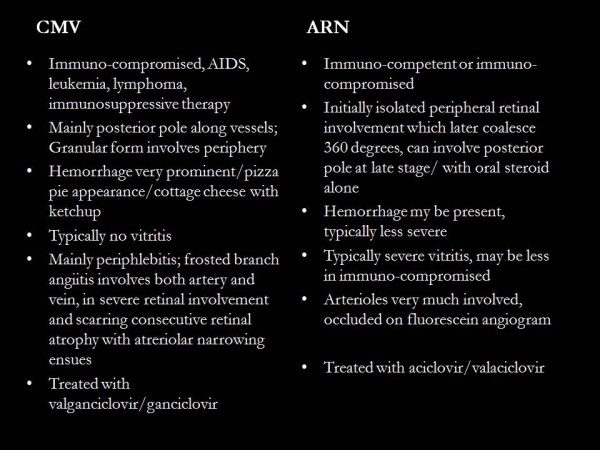

Most important characteristics are vitritis, occlusive retinal arteriolitis, and peripheral retinitis which becomes confluent in late stages. Compared to cytomegaloviral retinitis, the vitritis is extensive, retinitis is peripheral and hemorrhage is less.

The American Uveitis Society established the following as diagnostic criteria:

- One or more foci of retinal necrosis with discrete borders, located in the peripheral retina

- Rapid progression in absence of antiviral therapy

- Circumferential spread

- Occlusive vasculopathy, affecting arterioles

- Prominent vitritis and/or anterior chamber inflammation

Kyrieleis' Arteriolitis may be seen in ARN.[4]

Diagnostic procedures

The diagnosis of ARN is usually made based upon clinical characteristics. However, it is highly recommended to analyze an aqueous or vitreous sample to test for viral particles, especially in atypical or difficult diagnostic cases. Rarely, diagnostic vitrectomy or endoretinal biopsy may be necessary.

Lab tests

The following tests may be performed on aqueous or vitreous samples for further diagnostic certainty:

- Viral PCR

- Viral culture

- Use of direct or indirect immunofluorescence to identify viral antigens

- Measurement of viral antibodies

- Intraocular antibody titers with calculation of the Goldmann-Witmer coefficient

- Also rule out immunocompromise in all cases of retinitis especially HIV

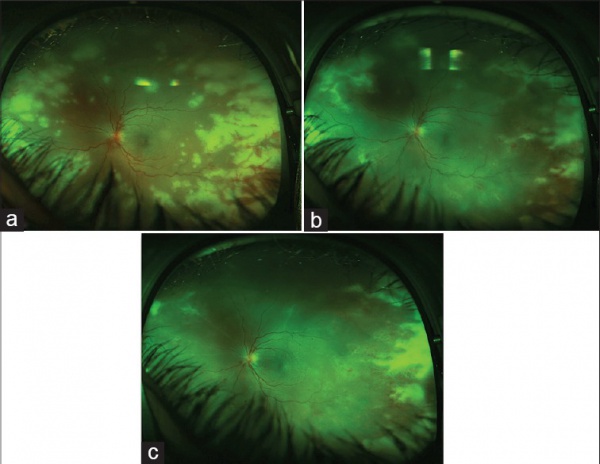

- Ultrawide field imaging (Optos) may be useful in documenting and following up the peripheral involvement in a single image.[3][5]

- Fundus fluorescein angiogram for occlusive arteritis

- Optical coherence tomography to document cystoid macular edema, epiretinal membrane

Differential diagnosis

- Progressive outer retinal necrosis

- CMV retinitis

- Toxoplasma chorioretinitis

- Acute multifocal hemorrhagic retinal vasculitis

- Syphilis

- Intraocular lymphoma or leukemia

- Bacterial/Fungal retinitis or endophthalmitis

- Behcet disease

- Sarcoidosis

- Sympathetic ophthalmia

- Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome

- Commotio retinae

- Central or branch retinal artery occlusion

- Ocular ischemic syndrome

- Collagen-vascular disease

- Retinoblastoma

Management

General treatment

Without intervention, the active phase of the disease can last between 6-12 weeks, while treatment with antivirals and/or steroids may reduce the latency to 4-6 weeks. ARN Treatment is complex and should be individualized based on overall clinical picture and vitreoretinal findings. Prospective, randomized controlled trials have not been performed given the rarity of the disease, and as such, treatment recommendations are based on case reports/series. Treatment modalities may include antiviral, anti-inflammatory, and antithrombotic therapy in cases with ischemic optic neuropathy, as well as laser photocoagulation for retinal detachment prophylaxis or surgery for retinal detachment repair.

Medical therapy

Antiviral therapy can be administered systemically (intravenously or orally) as well as via intravitreal injection. Prior to the mid-1990’s, intravenous (IV) administration of antiviral agents (usually acyclovir) was carried out for at least the first week after diagnosis of ARN because it was believed that higher serum and intraocular concentrations of the antiviral agent could be achieved; thereafter, it was considered appropriate to transition the patient to oral antivirals (acyclovir, famciclovir, valacyclovir, or valganciclovir) for an additional 4-12 weeks. With the advent of newer antiviral agents, many physicians now advocate the use of oral antiviral agents such as famciclovir, valacyclovir or valganciclovir as initial induction agents for treatment of ARN. Renal function should be monitored while patients are on systemic antivirals. Intravitreal delivery of antiviral agents, ganciclovir or foscarnet, is also a common practice. In a report by the AAO that evaluated the available evidence in peer-reviewed publications about the diagnosis and treatment of ARN, the authors found that there is level II and III evidence supporting the use of intravenous and oral antiviral therapy for the treatment of ARN. Data suggest that equivalent plasma drug levels of acyclovir can be achieved after administration of oral valacyclovir or intravenous acyclovir. The authors also found level II and III evidence suggesting that the combination of intravitreal foscarnet and systemic antiviral therapy may have greater therapeutic efficacy than systemic therapy alone. [6]The use of steroids and antithrombotic therapy (i.e. Aspirin) is controversial and may be used at the treating physicians’ discretion. Steroids may be started under the cover of antivirals and should never be started alone in the stage of acute retinitis.

Commonly used systemic antiviral agents include the following which can be tapered slowly over months following resolution of the acute herpetic phase of ARN:

- Acyclovir (13 mg/kg/dose divided every 8 h IV for 7 days, followed by 800 mg five times daily orally for 3–4 months)

- Famciclovir (500 mg orally q8h)

- Valacyclovir (1000–2000 mg orally q8h for induction)

- Ganciclovir (500 mg IV q12h)

- Valganciclovir (900 mg twice daily orally for 3 weeks induction, then 450 mg twice daily po for maintenance)

Antiviral agents administered intravitreally can provide beneficial adjunctive therapy, especially if retinitis is threatening the macula or optic disc:

- Ganciclovir (200-2000 ug per 0.1 mL)

- Foscarnet (1.2-2.4 mg per 0.1 mL)

Steroids may have a beneficial therapeutic effects if initiated 24-48 hours after the start of antiviral therapy or once regression of retinal necrosis been demonstrated:

- Prednisone (0.5-2.0 mg/kg/day orally for up to 6-8 weeks)

Aspirin may minimize vascular thrombosis and propagation of further retinal ischemia and necrosis. Topical steroid drops and cycloplegics have also been shown to be beneficial, depending upon the degree of anterior segment inflammation. Topical antiviral therapy has been shown not to be efficacious in treatment of ARN.

Medical follow-up

Patients with unilateral ARN should be closely followed with dilated examination of both of their eyes. Approximately 50-75% of patients with ARN will develop a retinal detachment. Reports of second eye involvement range from 3-35%, with variable involvement attributable to etiologic agent, course of therapy, and immune status. The antiviral therapy reduces the duration of active disease and reduces the chance of involvement of the fellow eye. However, the retinal detachment may not be reduced by antiviral therapy.

Surgery

The role of prophylactic laser retinopexy or early PPV is unknown. [7][8]Some retina specialists advocate the use of prophylactic laser along the posterior margin of the junction of necrotic and non-necrotic retina to prevent incidence of retinal detachment. The rates of success in preventing retinal detachment are variable, and consensus does not exist on whether laser demarcation should be employed. This may be due to the confounding fact that eyes in which laser can be successfully performed typically have optically clearer vitreous, less inflammation, and thereby less risk for developing retinal detachment.

Vitrectomy with or without use of scleral buckle, with either gas or silicone oil tamponade, is usually reserved for those cases in which tractional-rhegmatogenous retinal detachment occurs.

Complications

Many cases finally have less than 20/200 due to

- Retinal holes and tears

- Retinal detachment

- Proliferative vitreoretinopathy

- Vitreous hemorrhage

- Macular pucker

- Optic neuropathy- pallor of the optic disc

- Encephalitis

Primary prevention

The use of systemic or intravitreal antiviral agents reduces the duration of the active phase of ARN and may thereby potentially minimize the duration and extent of retinal necrosis. Chronic use of antivirals (for 6 weeks to 3 months) after resolution of the active phase of ARN in one eye has also been shown to reduce the incidence of ARN in the fellow eye.

Prevention of the late visual sequelae of acute retinal necrosis, namely that of retinal detachment, may be partially reduced through prophylactic laser photocoagulation of the retina surrounding areas of prior retinitis or atrophy. However, retinal detachment may still occur/progress even after laser. Laser may be difficult in view of painful red eye, severe media haze due to vitritis, posterior synechia, and cataract. Also, laser over the necrotic, swollen white retina may cause iatrogenic breaks.

Prognosis

The visual outcome of eyes affected by ARN is variable and largely depends upon vision at time of presentation as well as whether or not secondary retinal detachment or ischemic optic neuropathy occurs. Development of retinal detachment depends upon the extent of retinal necrosis present at the time of diagnosis, the amount of vitritis overlying areas of retinal necrosis (with more vitritis associated with a higher risk of RD), and varying response to treatment regimens.

Additional Resources

- Agarwal, A. “Acute retinal necrosis.” Gass’ Atlas of Macular Diseases, Fifth Edition, London: Elsevier, 2012, 900-907.

- Aizman A, Johnson M, Elner S. Treatment of Acute Retinal Necrosis Syndrome with Oral Antiviral Medications. Ophthalmology 2007, 114: 307–312.

- Aslanides IM, De Souza S, Wong DT, et al. Oral valacyclovir in the treatment of acute retinal necrosis syndrome. Retina 2002, 22: 352–354.

- Blumenkranz MS, Culbertson WW, Clarkson JG, et al. Treatment of the acute retinal necrosis syndrome with intravenous acyclovir. Ophthalmology 1986, 93: 296–300.

- Culbertson WW, Blumenkrantz MS, Haines H, et al. The acute retinal necrosis syndrome. Part 2: histopathology and etiology. Ophthalmology 1982, 89:1317–1325.

- Duker JS, Blumenkranz MS. Diagnosis and management of the acute retinal necrosis (ARN) syndrome. Surv Ophthalmol 1991, 35: 327–343.

- Emerson GG, Smith JR, Wilson DJ, et al. Primary treatment of acute retinal necrosis with oral antiviral therapy. Ophthalmology 2006, 113: 2259–2261.

- Ezra E, Pearson RV, Etchells DE, et al. Delayed fellow eye involvement in acute retinal necrosis syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 1995, 120:115–117.

- Figueroa MS, Garabito I, Gutierrez C, Fortun J. Famciclovir for the treatment of acute retinal necrosis (ARN) syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 1997,123: 255–257.

- Lau C, Missotten T, et al. Acute Retinal Necrosis. Ophthalmology 2007, 114: 756–762.

- Luu KK, Scott IU, Chaudhry NA, et al. Intravitreal antiviral injections as adjunctive therapy in the management of immunocompetent patients with necrotizing herpetic retinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol 2000, 129: 811–813.

- Palay DA, Sternberg P, Jr., Davis J, et al. Decrease in the risk of bilateral acute retinal necrosis by acyclovir therapy. Am J Ophthalmol 1991, 112: 250 –255.

- Tibbetts M, Shah C, et al. Treatment of Acute Retinal Necrosis. Ophthalmology 2010, 117: 818–824.

- Vemulakonda G, Pepose J, Van Gelder R. “Acute Retinal Necrosis Syndrome.” Retina, Fifth Edition, London: Elsevier, 2013, 1523-1531.

- Wong RW, Jumper JM, McDonald HR, et al. “Emerging Concepts In the Management of Acute Retinal Necrosis.” Br J Ophthalmol 2013;97:545–552.

References

- ↑ Urayama A, Yamada N, Sasaki T, et al. Unilateral acute uveitis with retinal periarteritis and detachment. Jpn J Clin Ophthalmol 1971;25:607–19.

- ↑ Young NJ, Bird AC. Bilateral acute retinal necrosis. Br J Ophthalmol 1978;62(9):581–90.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Tripathy K, Sharma YR, Gogia V, Venkatesh P, Singh SK, Vohra R. Serial ultra wide field imaging for following up acute retinal necrosis cases. Oman J Ophthalmol. 2015;8:71-2.

- ↑ Chawla R, Tripathy K, Sharma YR, Venkatesh P, Vohra R. Periarterial Plaques (Kyrieleis' Arteriolitis) in a Case of Bilateral Acute Retinal Necrosis. Semin Ophthalmol. 2017;32 :251-252.

- ↑ Tripathy K, Chawla R, Venkatesh P, Sharma YR, Vohra R. Ultrawide Field Imaging in Uveitic Non-dilating Pupils. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2017 ;12:232-233.

- ↑ Schoenberger SD, Kim SJ, Thorne JE, Mruthyunjaya P, Yeh S, Bakri SJ, Ehlers JP. Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute Retinal Necrosis: A Report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2017 Mar;124(3):382-392.

- ↑ Risseeuw S, de Boer JH, Ten Dam-van Loon NH, van Leeuwen R. Risk of Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment in Acute Retinal Necrosis With and Without Prophylactic Intervention. Am J Ophthalmol. 2019 Oct;206:140-148.

- ↑ Chen M, Zhang M, Chen H. EFFICIENCY OF LASER PHOTOCOAGULATION ON THE PREVENTION OF RETINAL DETACHMENT IN ACUTE RETINAL NECROSIS: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Retina. 2022 Sep 1;42(9):1702-1708.