Episcleritis

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

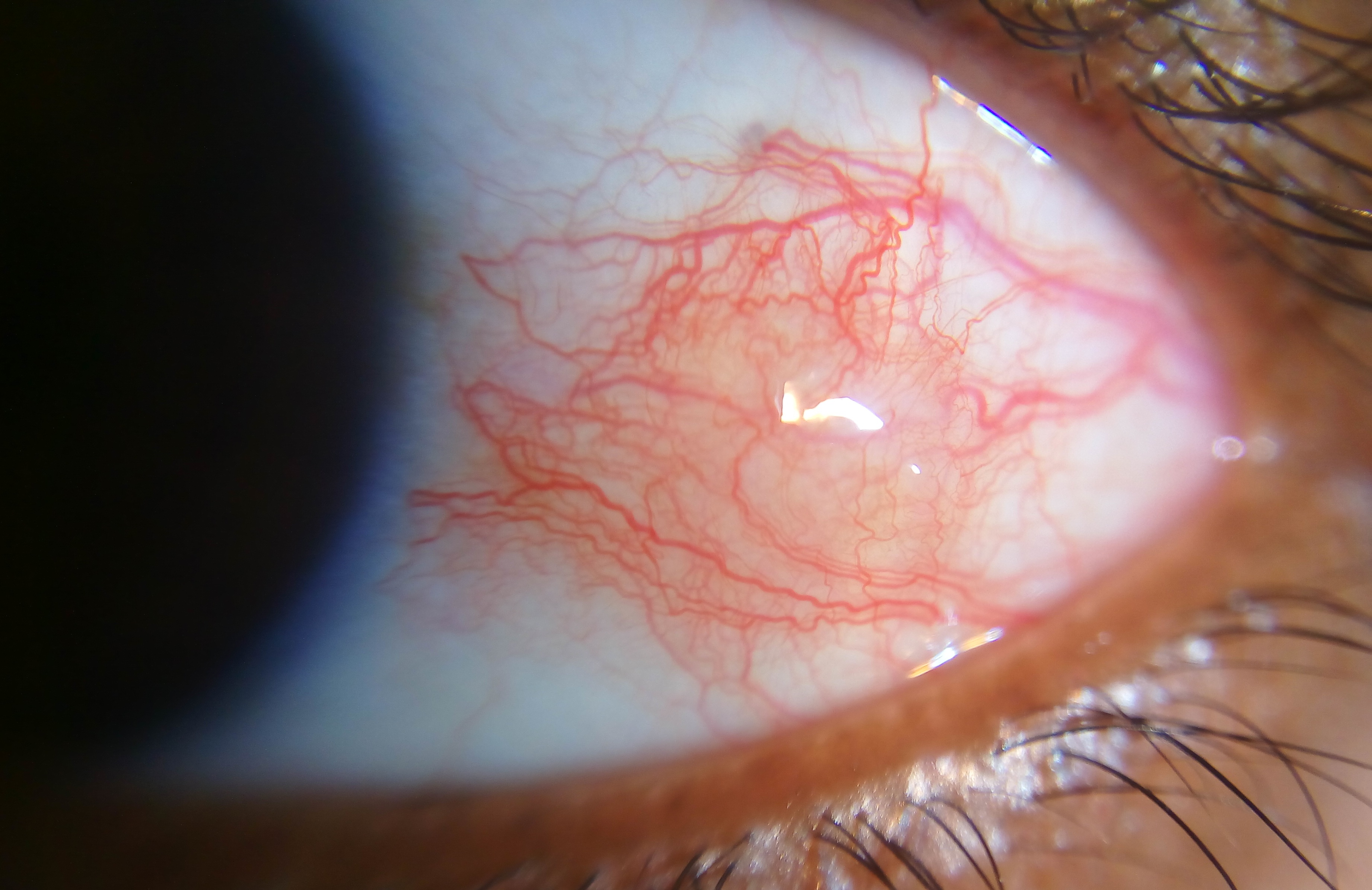

Episcleritis is a relatively common, benign, self-limited cause of red eye, due to inflammation of the episcleral tissues. There are two forms of this condition: nodular and simple. Nodular episcleritis is characterized by a discrete, elevated area of inflamed episcleral tissue. In simple episcleritis, vascular congestion is present in the absence of an obvious nodule.

A 2013 study estimated incidence of episcleritis as 41.0 per 100,000 per year and prevalence at 52.6. The simple variety is more common than nodular. According to one study, approximately sixty-seven percent of simple episcleritis is "sectoral" (involving only one sector or area of the episclera) and thirty-three percent is diffuse (involving the entire episclera).

Disease Entity

- H15.10 - Unspecified episcleritis

- H15.11 - Episcleritis periodica fugax

- H15.12 - Nodular episcleritis

Disease

Episcleritis is a relatively common, benign, self-limited inflammation of the episcleral tissues. There are two forms of this condition: nodular and simple. Nodular episcleritis is characterized by a discrete, elevated area of inflamed episcleral tissue. In simple episcleritis, vascular congestion is present in the absence of an obvious nodule.

The episclera is a fibroelastic structure consisting of two layers loosely joined together. The outer parietal layer, with the vessels of the superficial episcleral capillary plexus, is the more superficial layer. The superficial vessels appear straight and are arranged in a radial fashion. The deeper visceral layer contains a highly anastomotic network of vessels. Both of the vessel networks originate from the anterior ciliary arteries, which stem from the muscular branches of the ophthalmic artery. The episclera lies between the superficial scleral stroma and Tenon’s capsule. In contrast to simple episcleritis, nodular episcleritis has a less acute onset and more prolonged course.

Etiology

Most cases of episcleritis are idiopathic. Approximately 26-36% of patients have an associated systemic disorder. These include collagen-vascular diseases (rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, psoriatic arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, reactive arthritis (formerly Reiter’s syndrome), relapsing polychondritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and pustulotic arthro-osteitis), vasculitides (polyarteritis nodosa, temporal arteritis, Cogan’s syndrome, Churg-Strauss syndrome, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, Behcet’s disease), dermatologic disease (rosacea, pyoderma gangrenosum, Sweet’s syndrome), metabolic disease (gout), and atopy. The most common collagen vascular disease association is with rheumatoid arthritis. Malignancies, usually T-cell leukemia and Hodgkin’s lymphoma, can be associated with episcleritis. Foreign bodies and chemical injuries can also serve as inciting factors. Infectious agents do exist and include bacteria and mycobacteria. Uncommon infectious causes include Treponema (Syphilis), Borrelia (Lyme Disease), Chlamydia, Actinomyces, fungi, herpes zoster, herpes simplex, mumps, and chikungunya. Protozoa such as Acanthamoeba and Toxoplasmosis should be considered. Toxocara is another, albeit rare, cause. There has been at least one possible case of episcleritis as the initial presentation of COVID 19[1]. Lastly, medications such as topiramate and pamidronate can cause episcleritis.

Risk Factors

Most studies have shown that female adults are affected more commonly than male adults. However, one study of a pediatric population, revealed that boys were affected more commonly than girls. There are no specific risk factors; however, as mentioned above, a subset of patients will have an associated systemic disease. One study (Akpek et al)[2] found that 51% of patients have some concurrent eye disease.

General Pathology

In episcleritis, vascular congestion occurs in the superficial episcleral plexus. The episclera, as well as Tenon’s capsule, become infiltrated with inflammatory cells. The sclera is spared.

Pathophysiology

The exact mechanism for episcleritis remains a mystery.

Primary prevention

There is no primary prevention for episcleritis.

Diagnosis

History

Classically, patients 20-50 years old will present with either acute (simple episcleritis) or gradual (nodular episcleritis) onset of redness in the eye, possibly associated with pain. In simple episcleritis, the episode usually peaks in about 12 hours and then slowly resolves over the next 2-3 days. It tends to recur in the same eye or both eyes at the same time; over time, the attacks become less frequent and, over the years, disappear completely. The attacks may move between eyes. In nodular episcleritis, the redness is typically noted when the patient wakes up in the morning. Over the next few days, the redness enlarges, usually causing more discomfort, and takes on a nodular appearance. Episodes of nodular episcleritis are self-limited but tend to last longer than attacks of simple episcleritis.

Physical examination

The area of injection should be examined with the slit lamp. If the examiner uses a narrow, bright slit beam, nodular episcleritis can be distinguished from scleritis. In nodular scleritis, the inner reflection, which rests on the sclera and visceral layer, will remain undisturbed while the outer reflection will be displaced forward by the episcleral nodule. In scleritis, both of the light beams will be displaced forward. Also important to note is that the nodule in episcleritis is freely mobile over the scleral tissue that lies underneath.

Signs

Episcleritis is characterized by an area of diffuse or sectoral, bright red or pink bulbar injection, in contrast to the violaceous hue of scleritis. Eyelid edema and conjunctival chemosis may also be present.

Symptoms

Patients with episcleritis will report the acute or gradual onset of diffuse or localized eye redness, usually unilateral. Some may not report other symptoms, while others may report discomfort, photophobia, or tenderness. Complaints of severe pain or ocular discharge should prompt reconsideration of the diagnosis of episcleritis.

Clinical diagnosis

Episcleritis is a clinical diagnosis based primarily on history as well as external and slit lamp examination.

Diagnostic procedures

In practice, the differentiation of episcleritis and scleritis is often aided by the instillation of phenylephrine 2.5%. The phenylephrine blanches the conjunctival and episcleral vessels but leaves the scleral vessels undisturbed. If a patient's eye redness improves after phenylephrine instillation, the diagnosis of episcleritis can be made. According to Krachmer et al[3], phenylephrine 2.5% eye drops blanch conjunctival vessels, allowing the differentiation of conjunctivitis and episcleritis. Instillation of phenylephrine 10% will result in blanching of the superficial episcleral vascular network but not the deep plexus, thus distinguishing between episcleritis and scleritis.

Laboratory test

Single episodes of episcleritis do not require an extensive laboratory workup; however, patients who experience recurrent attacks and do not have any known associated diseases may require systemic evaluation. Tests to consider include rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibody, serum uric acid, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), complete blood count with differential, VDRL/FTA-ABS, urinalysis, PPD, chest x-ray, and HLA-B27. The choice of tests to be done in specific patients should be tailored for each individual based on the history, review of systems, and examination.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for cases of episcleritis includes conjunctivitis, phlyctenular conjunctivitis, scleritis, and, rarely, episcleral plasmacytoma. For nodular episcleritis, local causes such as a foreign body or granuloma should be ruled out as the causes for the episcleral nodule. The differential diagnosis might also include pingueculitis.

Management

Management is generally supportive alone.

General treatment

Episcleritis typically clears on its own without treatment, and reassurance is the primary step in management. Some patients, however, may experience significant pain or discomfort or may dislike the appearance of the condition. In such cases, supportive measures, such as cool compresses, cooled artificial tears, or medical therapy (see below), can be initiated.

Medical therapy

Oral NSAIDs (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs), typically 800 mg ibuprofen three times daily, are the mainstay of treatment for episcleritis. Alternative medications include indomethacin 25mg to 75 mg twice daily or flurbiprofen 100 mg three times daily. Studies comparing topical flurbiprofen and ketorolac to placebo found no difference in effectiveness in resolving the injection. The use of weak topical steroids (administered 1-4 times daily until symptoms resolve) is often employed[4][5]; however, some find their use controversial. Although they bring about a timely control of the condition, steroids may increase the risk of recurrence and cause ‘rebound’ redness followed by a more intense attack. In patients with collagen vascular disease, measures targeted at the underlying disease itself can achieve control of the episcleritis.

Episcleritis sometimes occurs in the setting of dry eye syndrome and blepharitis, and attention to these two underlying issues is likely to be of benefit.

Medical follow-up

Regular follow-up is not required unless a patient does not notice any improvement in his or her symptoms. Most isolated episodes of episcleritis resolve completely over 2-3 weeks. Those cases that are associated with systemic disease can take on a more prolonged course with multiple recurrences. Patients who are prescribed topical steroids should be monitored.

Surgery

There are no surgical therapies for episcleritis.

Complications

Episcleritis is mainly benign; however, there have been reports of a few complications in patients with recurrent disease. These include anterior and intermediate uveitis, as well as corneal dellen (adjacent to an episcleral nodule) and peripheral corneal infiltrates (adjacent to episcleral inflammation). Declining vision, in the setting of episcleritis, is typically attributed to advancing cataracts. Glaucoma has also been noted in a minority of patients. Both cataracts and glaucoma could be related to steroid use as part of the management of episcleritis.

Prognosis

Episcleritis is a benign, self-limited condition that usually resolves completely over the course of a few weeks.

References

General references:

- Kanski, Jack J. Clinical Ophthalmology: A Systematic Approach. China: Elsevier Inc, 201#

- External Disease and Cornea, Section # Basic and Clinical Science Course, AAO, 2010.

- Honik G, Wong IG, Gritz DC; Incidence and prevalence of episcleritis and scleritis in Northern California. Cornea. 2013 Dec;32(12):1562

Specific references:

- ↑ Otaif, Al Somali, Al Habash, " Episcleritis as a possible presenting sign of the novel coronavirus disease: a case report. AJO Case Reports, Vol 20, Dec 2020

- ↑ Akpek EK, Uy H, Christen W, et al. Severity of episcleritis and systemic disease association. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:729.

- ↑ Krachmer J, Mannis MJ, Holland EJ. Cornea. China: Elsevier, Inc, 201#

- ↑ Berchicci L, Miserocchi E, Di Nicola M, La Spina C, Bandello F, Modorati G. Clinical features of patients with episcleritis and scleritis in an Italian tertiary care referral center. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2014 May-Jun. 24 (3):293-8.

- ↑ Jabs DA, Mudun A, Dunn JP, Marsh MJ. Episcleritis and scleritis: clinical features and treatment results. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000 Oct;130(4):469-76. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(00)00710-8. PMID: 11024419.