CMV Retinitis

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) Retinitis is an acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)-related opportunistic infection that can lead to blindness. CMV retinitis occurred with higher frequency prior to the advent of antiretroviral therapy, but has since been decreasing in well-developed countries, although still remains a prevalent condition in developing countries. It is a viral retinitis that can also be seen in patients who are immunosuppressed for other reasons aside from AIDS.

Disease

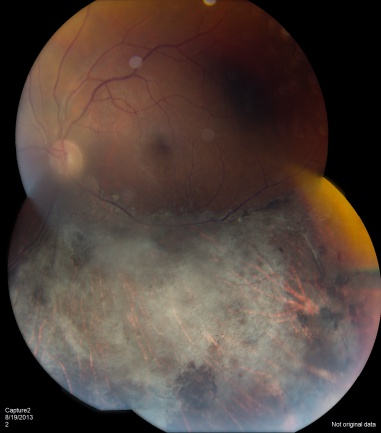

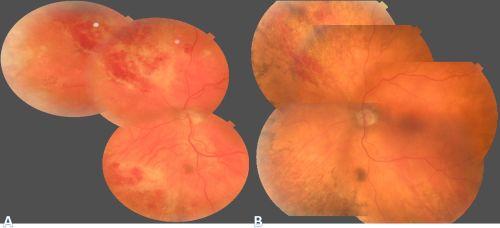

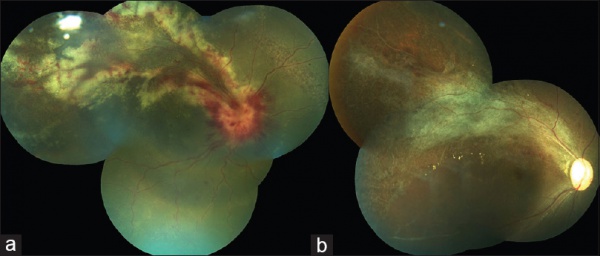

CMV is the most common opportunistic ocular pathogen in advanced HIV infection, typically occurring when CD4+ T-cell counts fall below 50 cells/μL. CMV retinitis results from hematogenous spread and reactivation of latent CMV, leading to retinal necrosis. Classic fundoscopic findings include confluent areas of retinal whitening with hemorrhages (“pizza pie retinopathy”), granular satellite lesions, and retinal vasculitis with perivascular sheathing. CMVR often leads to retinal atrophy and irreversible vision loss.

Etiology

CMV retinitis is caused by cytomegalovirus, a double stranded DNA virus in the herpes viridae family. It is often associated with HIV/AIDS and was extremely rare prior to the AIDS epidemic. It is also associated with severe immunosuppression from chemotherapy and autoimmune conditions requiring immunomodulators. With the advent of antiretroviral therapies, the incidence of CMV retinitis has decreased by 90% in AIDS population.

Risk Factors

Risk factors include HIV, CD4 count less than 50, or severe systemic immunosuppression. Recent reports have also demonstrated that local ocular immunosuppression can be a risk factor for CMV Retinitis. There have also been case reports of CMV retinitis in the absence of immunosuppression.

General Pathology

Infected cells show pathognomonic cytomegalic inclusions with large eosinophilic intracellular bodies. Electron microscopy can show the typical virus particles within infected cells. Histopathology shows full-thickness retinal necrosis that is eventually replaced by atrophic scar tissue, coagulative vasculitis, and choroiditis.

Pathophysiology

CMV reaches the retina hematogenously and infects the vascular endothelium which then spreads to the retinal cells. Impaired CD4 cell function permits uncontrolled CMV replication.

Primary Prevention

CMV retinitis has dropped in incidence and prevalence since the advent of HAART. The incidence has declined 55-99% and the odds of progression has reduced by 50% with HAART. Survival has improved from 0.65 years to greater than 1 year.

Patients with CD4 counts less than 50 cells/mm3 should be seen at least every 3 months to screen for CMV retinitis, as active retinitis is typically asymptomatic.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is largely clinical based upon the classic retinal findings and an immunosuppressive condition such as HIV; however, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis of the vitreous or aqueous can further support the diagnosis. Differentiation from acute retinal necrosis/ARN is vital as treatment is different.

History

Patients present with decreased visual acuity and floaters. Some may present with flashing lights (photopsias) or blind spots (scotomata). One study showed 54% were asymptomatic.

Physical Examination

Physical exam shows yellow white retinal lesions that often start in the periphery and follow the vasculature centripetally. However, it can start in the posterior segment. The classic findings are retinal hemorrhages with a whitish, granular appearance to the retina. Each lesion has the most activity in the borders. Vitreous signs of inflammation may be minimal as most patients are severely immunosuppressed. Very early CMV may resemble cotton wool spots, but with lesions larger than 750 µm, CMV must be considered. Three typical patterns have been described: a granular pattern, a fulminant/hemorrhagic appearance, or "frosted branch" angiitis.

Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment occurs in approximately one-third of patients when greater than 25% of the retina is involved. The presence of concurrent keratic precipitates in a stellate fashion can also suggest CMV uveitis.

Signs

CMV retinitis can present as: 1. Fulminant - hemorrhagic necrosis on white/yellow cloudy retinal lesions. They may be centered around vasculature. 2. Granular - Found more often in the retinal periphery with little to no necrosis and hemorrhage. 3. Perivascular - The classic "frosted branch" angiitis showing white lesions surrounding the retinal vessels.

Symptoms

Most patients are asymptomatic, but may have floaters, flashes (photopsias), blind spots (scotomata). Pain and photophobia are uncommon.

Clinical Diagnosis

The clinical diagnosis is made on history and classic retinal findings.

Retinal Zones of CMV retinitis

- Zone 1- 1 disc diameter surrounding the disc and 2 disc diameter around the fovea: immediately sight threatening

- Zone 2- Anterior to zone 1 and posterior to vortex vein ampullae

- Zone 3- Peripheral to Zone 2

Diagnostic procedures

Diagnostic procedures can include aqueous or vitreous tap to test for CMV and other herpes viruses.

Laboratory test

In cases of unknown retinitis, aqueous or vitreous tap and PCR analysis for CMV can be done. Serologic antibodies for CMV have not been shown to be helpful in diagnosis CMV retinitis-- a positive CMV antibody titer reflects prior exposure but does not diagnose the retinitis specifically, and a negative CMV antibody titer does not completely eliminate the chance of CMV retinitis, as patients who are immunosuppressed may not mount appropriate titers. The pooled incidence of blood CMV load <400 copies/mL has been reported to be 62% , ranging from 13% to 91%[1].

Differential diagnosis

Early CMV can resemble cotton wool spots. It may be confused with HIV retinopathy, which is actually more common the CMV retinitis. HIV retinopathy occurs in 50-70% of patients and is characterized by intraretinal hemorrhages, cotton wool spots, and microaneurysms. For small lesions that are hard to differentiate from cotton wool spots, serial exams should be performed, which will show enlargement of the CMV lesions. Immunosuppression should be treated like a spectrum; some patients are more immunosuppressed than other individuals. For cases of minor immunosuppression, CMV retinitis may present as acute retinal necrosis (ARN) syndrome but follows a chronic course similar to CMV retinitis, which may cause misdiagnosis.[2][3]

Syphilitic hemorrhagic necrotizing retinitis can mimick CMV retinitis; all patients should undergo treponemal testing.[4]

Management

Management is largely medically based with intravenous (IV), oral, and intravitreal anti-viral medications. Topical corticosteroids can be used to treat anterior chamber inflammation. Management also hinges on HAART in HIV positive patients.

Patients should be started on high dose induction therapy, which is followed by continuous maintenance therapy until CD4 counts increase, HAART is therapeutic, and CMV retinitis shows no progression.

General treatment

There are at least 8 options for therapy of CMV retinitis.

- Oral valganciclovir

- Intravenous ganciclovir

- Intravenous foscarnet

- Intravenous Cidofovir

- Intraocular ganciclovir device

- Intravitreal ganciclovir

- Oral leflunomide

- Oral letermovir

| Valganciclovir/Ganciclovir | Myelosuppression - Concomitant use of Granulocyte-Monocyte Colony Stimulating Factor (GM-CSF) can help reduce this risk. Thrombocytopenia occurs in 5-10% of patients. Potentially embryotoxic (discontinue nursing). |

|---|---|

| Foscarnet | Renal dysfunction with electrolyte abnormalities. Increased risk of seizures. Anemia. |

| Cidofovir | As high as 50% of patients taking cidofovir may experience ocular hypotony and anterior uveitis. Renal dysfunction. |

Medical therapy

First line therapy is generally oral valganciclovir, which is a pro-drug of ganciclovir. The induction dose is 900 mg twice daily for 21 days followed by maintenance of 900 mg daily. Valganciclovir has increased bioavailability compared to oral ganciclovir and does not require IV administration, making it a favorite for patients and doctors alike. However, the cost of therapy is high and patient compliance can be a problem especially in developing countries. Should be avoided if hemoglobin is <8gm%, absolute neutrophil count is less than 500 cells/µL, and the platelet count is less than 25,000/µL.

IV ganciclovir is given at 5 mg/kg twice daily for two to three weeks as induction therapy then followed by daily 5 mg/kg infusions. This can be quite cumbersome to patients.

Foscarnet is given at 90 mg/kg twice daily for two weeks followed by maintenance therapy of 90-120 mg/kg daily through IV infusion.

Cidofovir has a longer half life and can be administered weekly during induction followed by bi-weekly maintenance therapy. The dose is 5 mg/kg weekly during induction, and 5 mg/kg every other week during maintenance. Cidofovir can cause severe nephrotoxicity, so is typically given with saline hydration and high-dose probenecid therapy.

Oral ganciclovir can be considered for maintenance therapy but regression and involvement of fellow eye is more frequent.

Intravitreal ganciclovir, foscarnet, or cidofovir can be considered for short-term management.

Other options for therapy are oral leflunomide and oral letermovir. These therapies are using much less often but have been effective in patients that are experiencing side effects of other medications. [5] [6] [7] [8] [9] [10] [11] Maribavir, a director UL97 inhibitor, has also demonstrated efficacy in treating resistant strands which may be a forthcoming viable systemic treatment option.[12]

| Recommended treatment regime | Alternate regime | Remarks |

|

Induction -Oral Valganciclovir 900 mg twice daily -Intravenous Ganciclovir 5 mg/kg twice daily for 14-21 days -Intravitreal Ganciclovir 2 mg/0.1 mL twice weekly

-Oral Valganciclovir 900 mg daily -Intravenous Ganciclovir 5mg/kg/day -Intravitreal Ganciclovir 2 mg/0.1 mL weekly |

Induction

- Intravenous Foscarnet 90 mg/kg twice daily for 14 days -Intravenous Cidofovir 5 mg/kg weekly for 3 weeks Maintenance -Intravenous Foscarnet 120 mg/kg/day -Intravenous Cidofovir 5 mg/kg every 2 weeks Intravitreal Induction -Foscarnet 1.2-2.4 mg 1-2 times weekly -Cidofovir 20 μg 1-8 times as needed to halt retinitis Intravitreal Maintenance -Foscarnet 1.2 mg weekly -Cidofovir 20 μg every 5-6 weeks |

Ganciclovir/Valganciclovir: Myelosuppression Foscarnet: Nausea and vomiting, electrolyte disturbance, nephrotoxicity Cidofovir: nephrotoxicity, anterior uveitis CMV mutations in UL54 or UL97 genes cause ganciclovir, foscarnet and cidofovir resistance [62] |

Of note, Cidofovir should not be used if immune recovery is expected due to its association with IRU.

In patients with immediately sight-threatening lesions (lesions close to the macula or optic nerve head), intravitreal injection of ganciclovir (2mg in 0.1 mL injection) or foscarnet (2.4 mg in 0.1 mL injection) or fomvirsen 330 micrograms, or cidofovir 20micrograms with concurrent systemic therapy can be done.

CMV retinitis can be become drug resistant the longer the duration of treatment lasts. Resistance can be caused by immunosuppression after organ or hematopoietic stem cell transplants, where specifically ganciclovir and valganciclovir resistance have been reported.[13] [14] [15] [16] [17]

Medical follow up

Depending on the medication used, complete blood counts, chemistries, and intraocular pressure checks will be needed. Dilated eye exams should be performed at least weekly initially, then 2 weeks after induction therapy, followed by monthly thereafter while the patient is on anti-CMV treatment. Fundus photographs can be helpful to detect early relapse.

Patients should be followed in an appropriate HIV clinic with CD4 counts and viral load studies.

Surgery

The only initial surgical management involves intravitreal placement of intraocular ganciclovir devices. They have a relatively low risk profile and can last 6-8 months. They afford no protection to the fellow eye, however. In addition these implants are not readily available.

Surgery can also be performed for complications of retinitis that include rhegmatogenous retinal detachments.

Surgical follow up

Look for complications of silicone oil especially cataract and glaucoma. Many patients are one-eyed and silicone oil may need to be left for long duration.

Complications

The most serious complication of therapy for CMV retinitis, besides those listed above due to medications is immune recovery uveitis (IRU).

IMUNE RECOVERY UVEITIS (IRU)[18]

Immune recovery uveitis (IRU) is a form of intraocular inflammation associated with immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS), typically occurring in HIV-infected patients with a history of cytomegalovirus (CMV) retinitis following the initiation of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). It reflects a dysregulated immune response to residual CMV antigens in the setting of rapid immune restoration and remains a leading cause of vision loss in this population due to complications such as cystoid macular edema, epiretinal membranes, and optic disc edema.

NOTE: IRU is increasingly recognized beyond HIV, with IRU-like manifestations described in non-HIV individuals recovering from immunosuppression due to malignancy, transplantation, or autoimmune disease. These cases suggest a broader spectrum of immune recovery-associated uveitis, not limited to CMV or HIV.

Epidemiology

The incidence of IRU varies and is influenced by factors such as the HAART era and immune status at the time of initiation. Early reports estimated that IRU occurred in 10-17% of CMV retinitis (CMVR) cases during the initial HAART era, with over half of the cases developing inflammation after only a modest increase in CD4+ T-cell count (100–150 cells/mm³).

The timing of HAART initiation in CMVR is critical. Starting HAART before completing CMV induction therapy increases the risk of IRU. Conversely, controlling CMVR prior to immune reconstitution significantly reduces both the occurrence and severity of IRU. Ongoing anti-CMV therapy is advised to suppress viral antigen load until adequate immune recovery is achieved.

Pathophysiology

HAART has reduced the incidence of CMVR but has introduced immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS), a paradoxical inflammatory response to residual or subclinical infections. IRIS typically develops within 3 months of HAART initiation but can occur up to 12 months later. Diagnostic criteria for IRIS include:

1. Confirmed HIV infection

2. Temporal association with HAART

3. Immunologic response (↓ HIV RNA, ↑ CD4+ count)

4. Clinical deterioration due to inflammation

5. Exclusion of other causes

IRU is the most common ocular manifestation of IRIS and is considered an immune-mediated inflammatory response to residual intraocular CMV antigen. It can develop weeks to months after HAART initiation, even in the absence of active retinitis. The inflammation is believed to be driven by persistent antigenic stimulation within the eye, despite systemic viral suppression and anti-CMV therapy.

Biomarkers

Biologic markers may help distinguish IRU from active CMVR:

· Cytokine profile: Elevated IL-12, reduced IL-6, and absence of detectable CMV DNA in aqueous or vitreous samples suggest IRU rather than active infection.

· Inflammatory mediators: Increased levels of IP-10, PDGF-AA, G-CSF, MCP-1, fractalkine, and Flt-3L have been identified in the aqueous humor of IRU patients, indicating a distinct immunologic signature.

· HLA associations: IRU has been linked to specific HLA haplotypes, including HLA-A2, HLA-B44, HLA-DR4, and HLA-B8-18, which may predispose individuals to heightened inflammatory responses during immune recovery.

Clinical Presentation

IRU is a clinical entity with variable manifestations, ranging from anterior uveitis to severe vitritis, with potential complications that can significantly impact visual function. The severity of inflammation is influenced by several factors, including the degree of immune reconstitution, the extent of CMVR, the amount of intraocular CMV antigen, and previous treatment.

1. Symptoms: Floaters and moderate vision loss (typically between 20/40 to 20/200).

2. Inflammation: Anterior chamber inflammation and vitreous haze often develop after HAART initiation.

3. CMVR Activity: Active CMVR is not typically present in IRU, as improved immune function controls the infection.

Complications

· Cystoid macular edema (CME): The most common cause of vision loss in IRU, with a 20-fold increased risk.

· Anterior segment inflammation

· Synechiae

· Cataracts

· Vitreomacular traction

· Epiretinal membrane (ERM) formation

· Macular hole

· Proliferative vitreoretinopathy and retinal detachment

· Frosted branch angiitis

· Papillitis

· Neovascularization of the retina or optic disc

· Uveitic glaucoma

Risk Factors

Several risk factors have been identified for the development of IRU:

· Increased CD4+ T-cell count: A rapid rise in CD4+ count (100–199 cells/μL) is strongly associated with higher IRU risk (OR 21.8).

· Intravitreal cidofovir (OR 19.1).

· CMVR extension ≥25% (OR 2.52).

Conversely, the following factors are associated with a reduced risk of IRU:

· Posterior pole lesion (OR 0.43).

· Male gender (OR 0.23).

· HIV viral load >400 copies/mL (OR 0.26).

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

IRU is an exclusionary diagnosis commonly observed in HIV patients on HAART who experience a significant rise in CD4+ T-cell count (>100 cells/mm³) and develop paradoxical intraocular inflammation in eyes with a history of CMVR or other ocular infections. The diagnosis requires ruling out other causes of inflammation, including drug toxicities (e.g., cidofovir, rifabutin), new infections (e.g., ocular tuberculosis, syphilitic uveitis, toxoplasmosis retinochoroiditis), and conditions like sarcoidosis.

NOTE: In non-HIV patients, IRU-like inflammation may occur following immune recovery after reduced immunosuppressive treatment, seen in conditions such as lymphoma, Wegener granulomatosis, Good Syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, leukemia, and after organ transplants (renal or bone marrow). These cases may present ocular inflammation resembling IRU due to the restoration of immune function. Diagnosis involves clinical evaluation and diagnostic tests, such as multimodal imaging, ocular PCR, and vitrectomy, to exclude other causes. A multidisciplinary team approach is essential for accurate diagnosis and management.

Management

The management of IRU involves considering various factors, including the extent and activity of the underlying CMV retinitis, the presence or absence of non-ocular IRIS, the site of intraocular inflammation, the existence of any associated ocular complications, particularly macular edema, and the patient’s general health.

Medical Treatment

· Topical corticosteroids: Used for anterior chamber inflammation.

· Observation: Mild vitritis without macular edema may be monitored without treatment.

· Oral corticosteroids or periocular injections: For severe vitritis or CME, though effectiveness is limited.

· Intravitreal corticosteroids: For refractory cases, but careful monitoring is needed to prevent complications like increased intraocular pressure and cataract formation, and CMVR reactivation, which can be prevented by restarting anti-CMV therapy

· Fluocinolone acetonide implants: May improve CME associated with IRU.

· Anti-VEGF agents: Aflibercept has shown effectiveness in treating IRU-induced CME, potentially due to its higher affinity for VEGF-A, VEGF-B, and PlGF.

Discontinuing antiretroviral therapy is not recommended because it reduces the CD4+ T lymphocyte count and increases the risk of opportunistic infections. Patients with CMVR who are receiving antiretroviral regimens should continue with anti-CMV maintenance therapy (Oral Valganciclovir 900 mg daily) until the IRU is resolved and sustained immune recovery is achieved (CD4+ T lymphocytes ≥ 100 cells/µL for 3-6 months). Even after discontinuation of anti-CMV therapy, patients with a history of CMVR should be closely monitored at 3-month intervals, as they remain at risk for recurrence. International guidelines recommend initiation of HAART within two weeks of commencing anti-CMV therapy in HIV/CMVR patients, although these recommendations are based on expert opinions and not empirical evidence.

Surgical Treatment:

Indications for surgery: Vitreomacular traction, ERM, cataract, and proliferative vitreoretinopathy may require surgical intervention to improve visual outcomes.

Prognosis

The prognosis was almost uniformly fatal prior to the advent of HAART. Now it carries a much better prognosis, but even with HAART and anti-CMV therapy, mortality is still increased after diagnosis of CMV retinitis.

Prognosis for patients with or without HIV infection, corticosteroid immunosuppression, and other risk factors all have similar visual outcomes. The strongest factor associated with poorer visual outcomes for all patients is retinal detachment.

Additional Resources

- Turbert D, Janigian RH. Cytomegalovirus Retinitis. American Academy of Ophthalmology. EyeSmart/Eye health. https://www.aao.org/eye-health/diseases/cytomegalovirus-retinitis-list. Accessed March 07, 2019.

References

- ↑ Zhao Q, Li NN, Chen YX, Zhao XY. Clinical features of Cytomegalovirus retinitis in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and efficacy of the current therapy. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2023 May 26;13:1107237.

- ↑ Ho M, Invernizzi A, Zagora S, et al. Presenting Features, Treatment and Clinical Outcomes of Cytomegalovirus Retinitis: Non-HIV Patients Vs HIV Patients. OcularImmunology and Inflammation. 2019;29:535-542.

- ↑ Schneider EW, Elner SG, van Kuijk FJ, et al. Chronic retinal necrosis: cytomegalovirus necrotizing retinitis associated with panretinal vasculopathy in non-HIV patients. Retina. 2013;33(9):1791–1799.

- ↑ Rissotto F, Scandale P, Miserocchi E. Ocular syphilis masquerading as CMV retinitis in a transplanted patient. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2023 Oct 10:11206721231206441.

- ↑ John, G.T., Manivannan, J., Chandy, S., Peter, S., and Jacob, C.K. Leflunomide therapy for cytomegalovirus disease in renal allograft recepients. Transplantation. 77:1460–1461, 2004.

- ↑ Levi, M.E., Mandava, N., Chan, L.K., Weinberg, A., and Olson, J.L. Treatment of multidrug-resistant cytomegalo- virus retinitis with systemically administered leflunomide. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 8:38–43, 2006.

- ↑ Dunn, J.H., et al. Long-term suppression of multidrug- resistant cytomegalovirus retinitis with systemically ad- ministered leflunomide. JAMA Ophthalmol. 131:958–960, 2013.

- ↑ Rifkin, L.M., Minkus, C.L., Pursell, K., Jumroendarar- asame, C., and Goldstein, D.A. Utility of leflunomide in the treatment of drug resistant cytomegalovirus retinitis. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 11:1–4, 2015.

- ↑ Avery, R.K. Update in management of ganciclovir- resistant cytomegalovirus infection. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 21:433–437, 2008.

- ↑ Avery, R.K., et al. Utility of leflunomide in the treatment of complex cytomegalovirus syndromes. Transplantation. 90:419–426, 2010.

- ↑ Turner N, Strand A, Grewal DS, Cox G, Arif S, Baker AW, Maziarz EK, Saullo JH, Wolfe CR. Use of Letermovir as Salvage Therapy for Drug-Resistant Cytomegalovirus Retinitis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2019 Feb 26;63(3). pii: e02337-18. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02337-18. Print 2019 Mar. PubMed PMID: 30642941; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6395918.

- ↑ Tsui, Jonathan C. MD1; Huang, Vincent BS1; Kolomeyer, Anton M. MD, PhD1; Miller, Charles G. MD, PhD1; Mishkin, Aaron MD2; Maguire, Albert M. MD1. Efficacy of Maribavir in Valganciclovir-Resistant Cytomegalovirus Retinitis. Retinal Cases & Brief Reports: November 16, 2022 - Volume - Issue - 10.1097/ICB.0000000000001372

- ↑ Jabs, D.A., et al. Cytomegalovirus resistance to ganciclovir and clinical outcomes of patients with cytomegalovirus retinitis. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2003;135:26–34.

- ↑ Jabs, D.A., Martin, B.K., Ricks, M.O., Forman, M.S., and Cytomegalovirus Retinitis and Viral Resistance Study Group. Detection of ganciclovir resistance in patients with AIDS and cytomegalovirus retinitis: correlation of geno- typic methods with viral phenotype and clinical outcome. J. Infect. Dis. 2006;193:1728–1737.

- ↑ Jabs, D.A., Enger, C., Forman, M., and Dunn, J.P. Incidence of foscarnet resistance and cidofovir resistance in patients treated for cytomegalovirus retinitis. The Cyto- megalovirus Retinitis and Viral Resistance Study Group. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1998;42:2240–2244.

- ↑ Jabs, D.A., Enger, C., Dunn, J.P., and Forman, M. Cyto- megalovirus retinitis and viral resistance: ganciclovir re- sistance. CMV Retinitis and Viral Resistance Study Group. J. Infect. Dis. 1998;177:770–773.

- ↑ Myhre, H.-A., et al. Incidence and outcomes of ganciclovir-resistant cytomegalovirus infections in 1244 kidney transplant recipients. Transplantation.2011;92:217– 223.

- ↑ Rodrigues Alves N, Barão C, Mota C, et al (2024) Immune recovery uveitis: a focus review. Graefe’s Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology 262:2703–2712. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-024-06415-y

- Vertes D, Snyers B, DePotter. Cytomegalovirus retinitis after low-dose intravitreous triamcinolone acetone in an immunocompetent patient: a warning fotr the widespread use of intravitreal corticosteroids. Int Ophthalmol 2010; 30 (5): 595-7.

- Schneider EW, Elner SG, van Kuijk FJ, et al. Chronic Retinal Necrosis: Cytomegalovirus necrotizing retinitis associated with panretinal vasculopathy in non-HIV patients. Retina 2013; 33 (9): 1791-9.

- Print: Wills Eye Manual. Sixth Edition. Section 12.9: Cytomegalovirus Retinitis. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2012.

- Basic and Clinical Science Course. Section 9: Intraocular Inflammation and Uveitis. Ocular Involvement in AIDS. 2010: AAO.

- Basic and Clinical Science Course. Section 12: Retina and Vitreous. 2010: AAO.

- Goldberg DE, et al. HIV-Associated Retinopathy in the HAART Era. Retina: The Journal of Retinal and Vitreous Diseases. 2005: 25;5. 634-49.

- Jacobson MA. Pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis of AIDS-related cytomegalovirus retinitis. In: UpToDate, Bartlett JG and Mitty J (Ed), UpToDate, Waltham, MA. (Accessed on May 16, 2015).

- Jacobson MA. Treatment of AIDS-related cytomegalovirus retinitis. In: UpToDate, Bartlett JG and Mitty J (Ed), UpToDate, Waltham, MA. (Accessed on May 16, 2015).