Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada Disease

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Introduction

Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada (VKH) disease is defined as a bilateral granulomatous panuveitis, with or without extraocular manifestations, affecting young adults.

Vogt in 1906 and Koyanagi in 1929 described the same disorder independently. It is characterized by chronic anterior uveitis, alopecia, vitiligo, and dysacusia. Harada, also in 1929, described a disorder of bilateral exudative retinal detachments, with posterior uveitis, accompanied by pleocytosis of cerebrospinal fluid.[1] All these descriptions were recognized to be manifestations of the same disease process, and in 1932, Babel suggested the term Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada (VKH) disease.

Epidemiology

The incidence of VKH varies, depending on the geographic location and the ethnicity encountered. The disease primarily affects persons of color. In Japan it accounts for 6.8% to 9.2% of uveitis cases.[2] In the United States it hovers around 1%-4%. The majority of the cases occur around the second and fifth decades of life. Women have been reported as being more affected than men; but this varies depending on the population studied.

Risk Factors

VKH typically affects more pigmented groups, such as Hispanics, Asians, Native Americans, Middle Easterners, and Asian Indians, but not blacks of sub-Saharan African descent. There is an association with HLA-DR1 and HLA-DR4 (subtype 0405). The disease appears to affect women more frequently than men, but no specific sex predilection has been established. [3][4][5]

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis is unknown but theories revolve around the possibility that a T-cell mediated autoimmune reaction against one or more antigens associated with melanocytes, melanin, and retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) may play a major role in the disease. The trigger is unknown, but cutaneous injury, or viral infection have been reported as possible factors in some cases. Although the exact target antigen has not been identified, possible candidates for target antigen include tyrosinase or tyrosinase-related proteins, an unidentified 75 kDa protein obtained from cultured human melanoma cells (G-361), and the S-100 protein. [6] [7][5]

Histopathology

A granulomatous process is seen during the acute phase, and a nongranulomatous inflammation is seen during the chronic phase. The primary pathological feature is a diffuse thickening of the uveal tract caused by a non-necrotizing granulomatous inflammation.[8] There is a presence of diffuse lymphocytic infiltration with collections of epithelioid cells and multinucleated giant cells.[6] Dalen-Fuchs nodules, representing granulomas between the RPE and Bruch membranes, can be observed.[9]

Immunocytology demonstrates uveal infiltrates composed of T-cells and HLA-DR+ macrophages; non-dendritic-appearing CD1 positive cells are in close proximity to melanocytes in the choroid. [10]

Clinical Features

The clinical features of VKH disease will vary, depending on stage of the disease. The 4 stages of VKH are the prodromal stage, uveitic stage, chronic stage and chronic recurrent stage.

The prodromal stage symptoms will resemble a viral illness. Headaches, fever, orbital pain, nausea, dizziness, and light sensitivity are present. The symptoms will last around 3-5 days. Within the first couple of days, the patient will begin to complain about blurred vision, photophobia, hyperemia of the conjunctiva, and ocular pain.[6][8] [11]

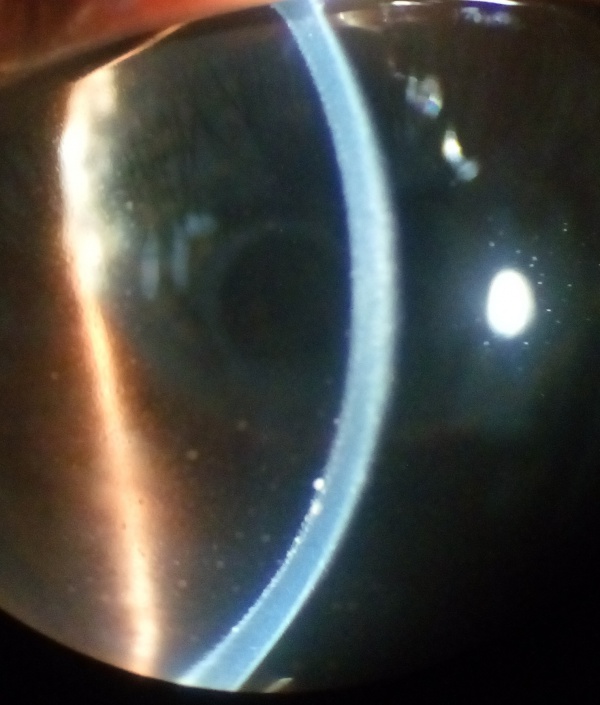

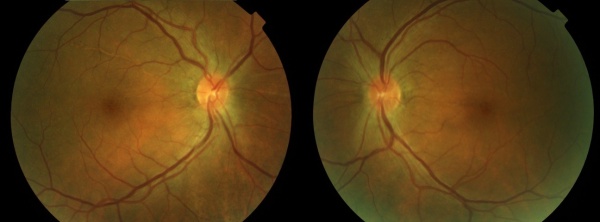

The uveitic stage presents with blurred visual acuity in both eyes (though one eye may be affected first, 94% will involve the second eye within 2 weeks).[12]The first signs of posterior uveitis include a thickening of the posterior choroid, manifested by elevation of the peripapillary retino-choroid layer, hyperemia and edema of the optic disk, and circumscribed retinal edema; accompanied by multiple serous retinal detachments. Eventually, the inflammation becomes more diffuse, affecting the anterior chamber, presenting itself as a panuveitis. [6][8][11][13]

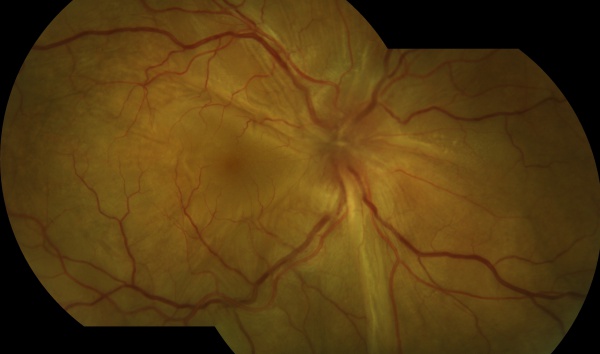

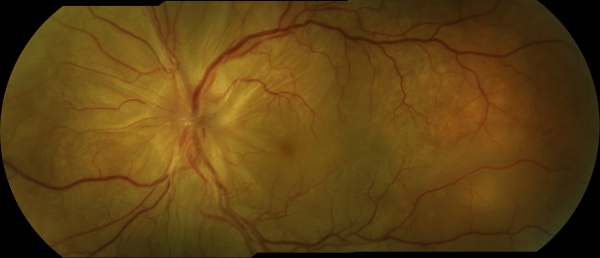

The chronic or convalescent stage will take place weeks after the uveitic stage. It is characterized by the development of vitiligo, poliosis, and depigmentation of the choroid.[11] Sugiura sign (perilimbal vitiligo) is the earliest depigmentation to occur,[13] presenting itself 1 month after the uveitic stage.[6] Choroidal depigmentation occurs several months after the uveitic stage, leading to a pale disc with a bright red-orange choroid known as a “sunset-glow fundus.” This phase may last several months.[11]

The recurrent stage consists of a panuveitis with acute exacerbations of anterior uveitis. Recurrent posterior uveitis with exudative retinal detachment is uncommon. Iris nodules may appear in this stage.[11] It is during this phase of the illness that most of the vision-threatening complications will develop (cataracts, glaucoma, subretinal neovascularization, etc.).[13]

Systemic Associations

- Auditory signs: These signs consist of sensorineural hearing loss with tinnitus and vertigo (usually present at the onset of the disease).

- Neurological signs: May include fever, headache, neck stiffness, nausea and vomiting.

- Dermal signs: Vitiligo can occur on the face, hands, shoulders and lower back about 2-3 months after the onset of VKH.

- Other signs: Poliosis and alopecia are often present.[9][3]

Diagnostic Criteria

The American Uveitis Society in 1978 recommended the following diagnostic criteria: (1) the absence of any history of ocular trauma or surgery; and (2) the presence of at least 3 of the following 4 signs: (a) bilateral chronic iridocyclitis; (b) posterior uveitis, including exudative retinal detachment; forme fruste of exudative retinal detachment; disc hyperemia or edema, and “sunset-glow” fundus; (c) neurologic signs of tinnitus, neck stiffness, cranial nerve, or central nervous system disorders, or cerebrospinal fluid pleocytosis; and (d) cutaneous findings of alopecia, poliosis, or vitiligo.[11][14]

Read and colleagues evaluated the existing criteria and concluded that it was inadequate for the diagnosis of VKH.[11] The revised Diagnostic Criteria for VKH Disease [5] was established at the First international Workshop on Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease as follows:

Complete Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease (criteria 1 to 5 must be present)

- No history of penetrating ocular trauma or surgery preceding the initial onset of uveitis

- No clinical or laboratory evidence suggestive of other ocular disease entities

- Bilateral ocular involvement (a or b must be met, depending on the stage of disease when the patient is examined)

- Early manifestations of disease

- There must be evidence of a diffuse choroiditis (with or without anterior uveitis, vitreous inflammatory reaction, or optic disk hyperemia), which may manifest as one of the following:

- Focal areas of subretinal fluid, or

- Bullous serous retinal detachments.

- There must be evidence of a diffuse choroiditis (with or without anterior uveitis, vitreous inflammatory reaction, or optic disk hyperemia), which may manifest as one of the following:

- With equivocal fundus findings; both of the following must be present:

- Focal areas of delay in choroidal perfusion, multifocal areas of pinpoint leakage, large placoid areas of hyperfluorescence, pooling within subretinal fluid, and optic nerve staining (listed in order of sequential appearance) by fluorescein angiography, and

- Diffuse choroidal thickening, without evidence of posterior scleritis by ultrasonography.

- With equivocal fundus findings; both of the following must be present:

- Late manifestations of disease

- History suggestive of prior presence of findings from 3a, and either both (2) and (3) below, or multiple signs from (3):

- Ocular depigmentation (either of the following manifestations is sufficient): Sunset glow fundus, or Sugiura sign.

- Other ocular signs: (a) Nummular chorioretinal depigmented scars, or (b) Retinal pigment epithelium clumping and/or migration, or (c) Recurrent or chronic anterior uveitis.

- Neurological/auditory findings (may have resolved by time of examination). a. Meningismus (malaise, fever, headache, nausea, abdominal pain, stiffness of the neck and back, or a combination of these factors; headache alone is not sufficient to meet definition of meningismus, however), or b. Tinnitus, or c. Cerebrospinal fluid pleocytosis.

- Integumentary finding (not preceding onset of central nervous system or ocular disease). a. Alopecia, or b. Poliosis, or c. Vitiligo.

- Early manifestations of disease

Incomplete Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease (criteria 1 to 3 and either 4 or 5 must be present)

- No history of penetrating ocular trauma or surgery preceding the initial onset of uveitis, and

- No clinical or laboratory evidence suggestive of other ocular disease entities, and

- Bilateral ocular involvement.

- Neurologic/auditory findings; as defined for complete Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease above, or

- Integumentary findings; as defined for complete Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease above.

Probable Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease (isolated ocular disease; criteria 1 to 3 must be present)

- No history of penetrating ocular trauma or surgery preceding the initial onset of uveitis.

- No clinical or laboratory evidence suggestive of other ocular disease entities.

- Bilateral ocular involvement as defined for complete Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease above.

Diagnostic Procedures

In the majority of cases, the diagnosis of VKH will be based on clinical findings. The following testing modalities are utilized to assist in the diagnosis and to follow the response to treatment.

Fundus Fluorescein Angiography (FFA)

During the acute stage of the disease, we find an early irregular focal or patchy fluorescence of the choroidal circulation. There exist various pinpoint areas of leakage at the level of the retinal pigment epithelium. In the later phases, the localized hyperfluorescent spots increase in size, coalesce, and expand into the subretinal space in areas of serous detachment leading to a large area of leakage. The optic disc can demonstrate blurred fluorescent margins accompanied by late leakage.

In the chronic stage of the disease, the presence of diffuse scattered pigmentary changes with markedly pigmented areas adjoining hypopigmented ones (“moth-eaten” appearance) are the hallmark. [11][15]

Soon-Phaik Chee and colleagues report findings in their retrospective study that indicate the importance of early pinpoint peripapillary hyperfluorescence as a prognostic factor in VKH. The absence of this sign suggests that the disease is no longer in its early stages, indicating the need for more aggressive and prolonged treatment to prevent future recurrences. [16]

Indocyanine Green Angiography (ICG)

ICG demonstrates an early choroidal stromal vessel hyperfluorescence and hypofluorescent dark spots during the early and midphase, distributed mainly posteriorly, and in excess of those seen clinically on FFA. The late phase will vary according to the current stage of the disease. During the active stage, the hypofluorescent spots fade and are replaced by hyperfluorescent ones (representing focal sites of active choroidal inflammation). In the chronic stage, the hypofluorescent dark spots are seen during all the phases of ICG, but they are unapparent during clinical or FFA evaluation. [12][15]

Fundus Autofluorescence (FAF)

In the active stage of the disease, FAF will show hyperautofluorescence in the macula with hypoautofluorescence in the areas of the serous detachment; returning to normal at 6 months after treatment is initiated.[6]

During the chronic stage, many different patterns can occur: decreased autofluorescence (due to peripapillary atrophy and multiple atrophic and pigmented scars), increased autofluorescence (patches or irregular areas of pigmentation and cystoid macular edema) and normal autofluorescence.[6]

Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT)

An OCT will demonstrate the presence of subretinal fluid. In the presence of subtle choroidal folds, they will be detected as corrugation of the RPE/choroid with choroidal thickening.[2][6] Multiple septae creating compartments or pockets of fluid in the outer retinal may be seen. Typically, the inner retina inward to the external limiting membrane is normal. There is increased choroidal thickness in acute stage.

Ultrasonography

During the acute stages of the disease, the ultrasound will present diffuse choroidal thickening with low to medium reflectivity, serous retinal detachments, vitreous opacities without posterior vitreous detachments, and scleral or episcleral thickening. [11] [17]

Electroretinography

Full-field electroretinography analysis demonstrated diffusely diminished amplitudes in both scotopic and photopic phases in patients in the chronic stages.[6]

Laboratory Tests

Spinal fluid examination reveals evidence of pleocytosis (which may persist for up to 8 weeks)[11] and elevation of protein levels in the early stages.

Differential Diagnosis

- Sympathetic ophthalmia

- Uveal lymphoid infiltration

- Intraocular lymphoma

- Ocular Lyme disease

- Sarcoidosis

- Uveal effusion syndrome

- Lupus choroidopathy

- Posterior scleritis

- Cat scratch disease

- Acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy (APMPPE)

- Acute leukemia

- Metastatic carcinoma

- Exudative retinal detachments due to malignant hypertension

- Central serous chorioretinopathy after steroid use

Treatment

In the acute phase, intravenous high-dose corticosteroids (IV methylprednisolone 1 g or IV dexamethasone 100 mg to run over 1 hour after excluding systemic infection and contraindications, under physician's supervision) are usually advised for 3 days followed by high-dose oral steroids to be tapered very slowly.

Treatment involves the prompt use of systemic corticosteroids administered orally at a dose of 1-1.5 mg/kg per day for a minimum of 6 months. Lai TY and colleagues reported that patients receiving treatment for less than 6 months were more likely to have recurrences (58.8%) compared to those treated for 6 months or more (11.1%). [18] The initial high dose is maintained for 2-4 weeks, followed by gradual tapering of the drug. Many authors differ in what should be considered first-line therapy in VKH disease, advocating the use of immunosuppressants as the treatment of choice. Some of the reasoning behind the use of immunosuppressive therapy is to avoid the many side effects associated with long-term corticosteroid use. Immunosuppressant therapy as first-line treatment has been associated with better visual acuity outcomes when compared to corticosteroid therapy along. [19] The immunosuppressants that have proven efficient in clinical trials are azathioprine (1-2.5 mg/kg/day) and cyclosporine A (3-5mg/kg/day).[20] Mycophenolate mofetil and rituximab have also been used.

It is important to remember that the administration of immunosuppressants should be closely monitored and evaluated alongside an internist for any complications or side effects from the treatment.

Complications

Read and colleagues reported at least 1 complication developed in 51% of eyes with VKH disease.[21] The most common complications are:

- Cataracts

- Glaucoma

- Choroidal neovascularization

- Subretinal fibrosis

- Choroidal atrophy

- Posterior synechiae

- Optic atrophy

Prognosis

Aggressive therapy, early detection, very slow tapering of oral steroids, and use of immunosuppressants are the keys to maintaining good visual acuity. The prognosis of the disease is dependent on the duration and the number of recurrent episodes of inflammation. [21] A poor final visual acuity is predicted by a greater number of complications, older age at disease onset, a longer median duration of the disease, delayed initiation of treatment, and greater number of recurrent episodes of inflammation. The better the visual acuity is at presentation, the more likely the final visual acuity is to be improved. [6][21][22]

References

- ↑ Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Working Group. Classification Criteria for Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada Disease. Am J Ophthalmol. 2021 Aug;228:205-211. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2021.03.036. Epub 2021 Apr 9. PMID: 33845018; PMCID: PMC9073858.

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 Agarwal, Anita. Gass’s Atlas of Macular Diseases, 5th Ed. China, Saunders; 2012:998-1002

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.0 3.1 Kanski Jack and Bowling Brad. Clinical Ophthalmology: A Systematic Approach, 7th Ed. El Sevier Saunders; 2011

- ↑ Huang Jogn and Gaudio Paul. Ocular Inflammatory Disease and Uveitis Manual: Diagnosis and Treatment, 1st Ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2010

- ↑ Jump up to: 5.0 5.1 5.2 Read RW, Holland GN, Rao NA, et al. Revised diagnostic criteria for Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease: report of an international committee on nomenclature. Am J Ophthalmol 2001;131:647–652

- ↑ Jump up to: 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 6.8 6.9 Attia S, Khochtali S, Kahloun R, Zaouali S, Khairallah M. Vogt – Koyanagi – Harada disease. Expert Rev. Ophthalmol. 2012; 7(6):565-585

- ↑ Weng Sehu K, Lee W. Opthalmic Pathology: An illustrated guide for clinicians. Massachusetts, Blackwell Publishing; 2005:174

- ↑ Jump up to: 8.0 8.1 8.2 Jakobiec, Albert. Principles and Practice of Ophthalmology, 3rd Ed, Vol #1. Edinburgh, Saunders; 2008:1201-1209

- ↑ Jump up to: 9.0 9.1 Yanoff Myron and Duker Jay. Yanoff & Duker: Ophthalmology, 3rd Ed. Mosby, 2008

- ↑ Yanoff M, Sassani J. Ocular Pathology, 6th ed. China,Mosby; 2009:97-98

- ↑ Jump up to: 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 11.7 11.8 11.9 Ryan, Stephen. Retina. 5th Ed. China:Saunders, 2013:1326-1336

- ↑ Jump up to: 12.0 12.1 Nussenblatt Robert and Whitcup Scott. Uveitis: Fundamentals and Clinical Practice, 4th Ed. Mosby El Sevier; 2010:303-318

- ↑ Jump up to: 13.0 13.1 13.2 Moorthy R, Inomata H, Rao N. Major Review – Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada Syndrome. Surv Ophthalmol 39:265-292,1995

- ↑ Snyder DA, Tessler HA. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 1980;90:69-75

- ↑ Jump up to: 15.0 15.1 Agarwal, Amar. Fundus Fluorescein and Indocyanine Green Angiography: A Textbook and Atlas. Slack Inc., 2008

- ↑ Soon-Phaik C, Aliza J, Chui Ming GC. The Prognostic Value of Angiography in Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada Disease. Am J Ophthalmol 2010;150:888-893

- ↑ Nguyen M, Duker J. Ophthalmic Pearls: Retina- Identify and Treat Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada Syndrome. American Academy of Ophthalmology, 2005. Web. April 19, 2015

- ↑ Lai T, Chan R, Chan C, Lam D. Effects of the duration of initial oral corticosteroid treatment on the recurrence of inflammation in Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. Eye (Lond). 2009; 23(3):543-548

- ↑ Paredes I,Ahmed M, Foster C. Immunomodulatory therapy for Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada patients as first-line therapy. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2006; 14(2):87-90

- ↑ Kim S, Yu H. The use of low-dose Azathioprine in patients with Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2007; 15(5):381-387

- ↑ Jump up to: 21.0 21.1 21.2 Read RW, Rechodouni A, Butani N, Johnston R, et al. Complications and prognostic factors in Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. Am J Ophthalmo 2001;131:599-606

- ↑ Read RW. Vogt-Koyanagu-Harada disease. Ophthalmol Clin N Am 15 (2002)333-341