Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis Associated Uveitis

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

This article describes the features of chronic uveitis occurring in the setting of a Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (JIA)

Disease Entity

Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (JIA) and Chronic Uveitis

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) (formerly juvenile rheumatoid arthritis or chronic arthritis) is defined as arthritis of at least 6 weeks of duration without any identifiable cause in children younger than 16 years. [2] Chronic Uveitis is defined as a persistent uveitis characterized with prompt relapse in less than 3 months after discontinuation of therapy.[2] This is the most common cause of uveitis in children, accounting for up to 47% of all types of uveitis seen in children. This disease is most common in North America, Scandinavia, United Kingdom, and Germany.

Etiology

The interaction between environmental factors and multiple genes has been proposed as the most relevant working mechanism to the development of (JIA). Development might be initiated and sustained by the exposure to environmental factors, including infectious agents which affect people at a young age, depending on the underlying genetic predisposition to synovial inflammation. Data from patients with (JIA) suggest a scenario in which different external antigens elicit multiple antigen-specific pathways, cytotoxic T cell responses, activation of classical complement cascade, and production of pro-inflammatory cytokines. [3]

Risk Factors

The risk factors in a Juvenile Idiopathic arthritis patient for developing uveitis include: [4][5]

- The pattern of initial presentation of arthritis; Oligo-arthritis

- Gender; female

- Status of the ANA; positivity

- Age at onset of arthritis before 4 years old

- Presence of HLA-DRB1or HLADRB1*

- rheumatoid factor negative test

Uveitis typically presents after arthritis develops, but in 3-7% can have uveitis develop before arthritis. Median time interval for development of uveitis is 5.5 months. Approximately 20% of children with oligoarticular JIA (four or fewer joints involved) develop uveitis, while polyarticular onset JIA patients experience uveitis at a lower rate (about 5%). Of those who will develop uveitis, over 90% do so within 4 years of diagnosis of joint disease.

General Pathology

Pathophysiology

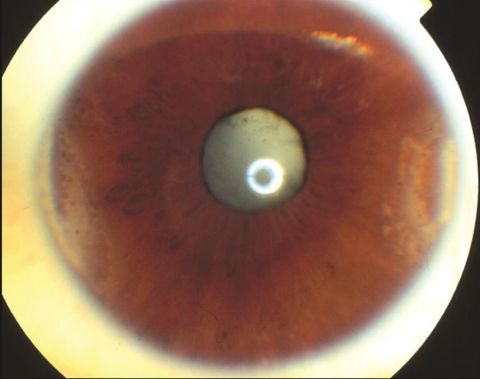

The pathogenesis of the anterior uveitis associated with JIA is unknown, but it is likely to have an immunologic basis. JIA-associated uveitis is usually bilateral and non-granulomatous with fine to medium sized keratic precipitates, but some African Americans, may have granulomatous precipitates. Chronic inflammation may produce band keratopathy, posterior synechiae, ciliary membrane formation, hypotony, cataract, glaucoma, and phthisis.[6]

Diagnosis

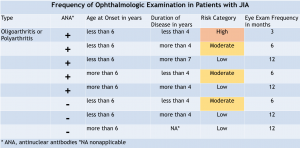

Diagnosis is often made during an ocular screening examination, which is vital for these at-risk patients subject to asymptomatic vision loss. Screening guidelines continue to undergo revision but are based on 4 risk factors for developing uveitis (see Table 1) :

- Category of arthritis

- Age at onset of arthritis

- Presence of ANA positivity

- Duration of the disease[8]

History

Initially, the patient with intraocular inflammation associated with JIA shows no classic signs or symptoms of uveitis, such as: red eye, pain, photophobia and blurred vision.[9] This stage is critical in developing eye disease, because the lack of events can last from several months to years, and it is not until the first complications of uveitis appear that their relatives or the physician detect its presence.[10] The exception is male patients with HLA-B27 positivity who may present with severe inflammation and the typical symptoms of redness, pain, and photophobia. These patients are usually older. Compared to other forms of uveitis that develop in adulthood, the risk of irreparable damage and the associated reduction in quality of life is still very high for children with JIA-associated uveitis. Thus, it is particularly important that these patients receive adequate treatment early on before permanent damage has developed.[11]

Physical Examination

In addition to joint examination, a full ocular examination is indicated.

Examination may be difficult in very young patients, and in some cases, examination under anesthesia (EUA) will be required. Medical therapy and compliance may also be difficult in young children. [12] Unique to young children is the possibility of developing amblyopia from media opacities or macular edema.[12]

It is during the chronic stage of the disease that regular ophthalmologist visits are key for the detection of intraocular inflammation, which can only be noted through careful observation under slit lamp examination.[10] Posterior segment examination should also be undertaken to detect inflammation of the optic nerve, retina, and cystoid macular edema.

Clinical diagnosis

Screening of children with JIA for uveitis involves a combination of slit lamp examination, measurement of intraocular pressure and age-appropriate visual acuity testing. A slit lamp allows examination of the anterior and posterior chambers as well as the posterior pole. A diagnosis of uveitis is made based on features of inflammation on slit lamp examination. These include cells in the anterior chamber and anterior chamber flare resulting from protein leakage into the anterior chamber due to breakdown of the blood–aqueous humor barrier. [13]

The criteria proposed by the SUN group provide a grading system for intraocular inflammation, and takes into account anterior chamber cells, anterior chamber flare, vitreous cells, and vitreous haze or debris.[2] Other findings include band keratopathy, posterior synechiae, cataract, and glaucoma.

Diagnostic procedures

Several structural complications can occur in the setting of JIA that contribute to visual loss. In the light of a patient with the diagnosis of Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis attention to detect the following complications should be paid:

- Band keratopathy

- Posterior synechiae

- Cataract

- Glaucoma

- Hypotony

- Macular edema

- Epiretinal membrane

- Optic disc edema

The need for functional, age-appropriate assessment of vision during uveitis screening has been highlighted by Heiligenhaus et al. who have developed guidelines for measuring outcome in JIA and included assessment of VA as a key outcome.[11]

Visual acuity, Intraocular pressures, slit lamp examination, refraction under cycloplegia, and dilated examination of the posterior pole are the basic procedures to be performed in a first visit to a patient with the diagnosis or the presumed diagnosis of Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis, an ultrasound, and the Exam Under Anesthesia (EUA) may be required for particular cases.

Laboratory test

Many laboratory tests can be performed in the diagnostic work up for uveitis in children based on systemic symptoms and ocular disease. Labs specifics for JIA include Anti-nuclear antibodies (ANA), Complete blood count (CBC), Rheumatoid factor (RF), and HLA-B27 antigen. Specifically ANA positivity increases the risk of the development of uveitis in Oligoarticular JIA in up to 45% of patients. In Polyarticular JIA RF negative patients uveitis is reported in 5-10% of patients and is often bilateral. In Polyarticular JIA RF negative uveitis risk is lower. In Enthesitis related arthritis, HLA B27 tends to be positive and uveitis is noted in 7-15% of patients that is often acute, recurrent anterior uveitis.

Differential diagnosis[14]

Other anterior uveitis in the pediatric population:

- Psoriatic arthritis

- Enthesitis-related arthritis also been referred to as juvenile ankylosing spondylitis

- Tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis (TINU) syndrome

- Kawasaki disease, also known as mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome

- Idiopathic

- Trauma

- Post-infectious

Intermediate uveitis:

- Sarcoidosis

- Syphilis

- Lyme disease

- Multiple sclerosis

- Tuberculosis

- Idiopathic disease, known as pars planitis, accounts for more than 90% of cases in the intermediate uveitis.

Posterior Uveitis:

Panuveitis:

- Sarcoidosis

- Familial juvenile systemic granulomatosis (Blau syndrome)

- Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome

Management

Management of JIA associated uveitis is complex and usually involves co-management with a pediatric rheumatologist. There is the management of the systemic disease and the ocular disease. Here we will be discussing the specifics of the treatment of the ocular disease.

General treatment

Initial treatment of the uveitis, typically anterior uveitis is the administration of topical corticosteroids and cycloplegia. Increased IOP and cataracts are well known complications of topical steroid use, and must be continually monitored while using topical corticosteroids. In severe cases of inflammation oral corticosteroids can be used. This is the same treatment for acute uveitis flares. [15]

Systemic immunosuppression therapy is recommended for any patients using 1-2 drops daily for continued uveitis control. [16]

Methotrexate (MTX) is a well-established first-line IMT in the management of JIA-associated uveitis [17] Other disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (cDMARDs) have been considered for those with chronic anterior uveitis and JIA such as azathioprine, leflunomide, mycophenolate and cyclosporine; however, use of these agents are limited due to adverse effects and reports of refractory uveitis.[18]

If a patients fail therapy with an anti-metabolite biologic agents such as adalimumab and infliximab are effective and well-tolerated in children with uveitis.[19] [20]

Medical therapy

JIA-associated uveitis is one of the most difficult eye diseases to manage. Both the inflammation and the frequent use of topical and systemic steroids result in frustrating complications. [15]

Controlling the inflammation is the best way to prevent complications and reduce the need for surgical intervention. Early introduction of Immunomodulatory therapy in cases of JIA-associated uveitis is the best way to prevent complications by controlling the ongoing inflammation and inducing remission.[15] While first line treatment with a steroid sparing agent is with MTX as above, in severe JIA-associated uveitis new recommendations include combining MTX therapy with an anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF)a biologic. Adalimumab has been shown to have greater efficacy than infliximab and etanercept in overall control of intraocular inflammation. Anti TNFa agents have a relatively strong safety profile, and have rare adverse reactions.[15] [21] Second line therapies include Abatacept, a CRLA-4 inhibitor, or tocilizumab (another off label anti TNFa). Rituximab has been studied in a few case series, however there are no conclusive evidence at this time this drug fully treats the disease.[18]

Medical follow up

In the light of an ongoing uveitis or signs of chronic intraocular inflammation, the follow up should be aimed to stop the uveitis and to address the complications derived from the chronic inflammation or medical treatment. JIA patients with inactive who are tapering or discontinuing therapy should be monitored frequently for relapse. The 2019 American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation Guideline for the Screening, Monitoring, and Treatment of Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis-Associated Uveitis recommends ophthalmic examination within a month of tapering or discontinuing topical corticosteroids and ophthalmic examination within 2 months of tapering/discontinuing systemic therapy. [22]

Surgery

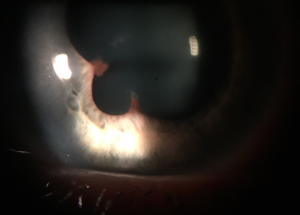

Cataract extraction with intraocular lens implants has been carried out with a measure of success in non-uveitic pediatric eyes, but in cases of uveitis, multiple factors affect the final outcome.

It is important to ensure a two-step process while planning cataract surgery.

- Ensure that the inflammation is controlled for at least three months[23]

- Strict control in the postoperative period[24]

Some authors suggested that delaying the placement of IOL by about 1 year after cataract extraction significantly reduced secondary glaucoma and retrolental membranes while maintaining similar visual acuity as primary IOL placement in JIA–uveitic cataracts.[25]

According to Terrada children with JIA–uveitis, usually require cataract surgery around 9.8 years of age.[26] Making the Intraocular Lens calculations very difficult to predict due to the changing axial lengths and anterior chamber depths of growing eyes.

In the 1990´s most surgeons supported the thesis that after the cataract extraction the patient remained aphakic and lensectomies and vitrectomies were preferred in the earlier days of the phaco surgery, however recent evidence (Quinones et al.) reported a 92 % improvement in visual outcome in eyes with polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) posterior chamber implants (PCIOLs) placed in the bag. The authors noted no difference in postoperative inflammation between patients who received an IOL and those who did not.[27]

Although there is not a definitive answer and every case should be evaluated individually.[28]

Complications

In a major cohort study, the reported rate of ocular complications in children with JIA-associated uveitis was as high as 67%.

- Band keratopathy 32%

- Posterior synechiae 28%

- Cataract 22%

- Ocular hypertension 15%

- Hypotony 9%.

- Optic nerve edema 4%

- Epiretinal membrane formation 4%

- Macular edema in 3%

The same group of Investigators also found that one-third of the children had impaired vision at presentation and almost one-quarter of these patients presented with legal blindness in at least one eye.[29]

The high rate of cataract in JIA-associated uveitis makes cataract extraction, with or without intraocular lens (IOL) implantation, the most frequent surgical procedure in patients with JIA-associated uveitis.[9] The chronic use of topical corticosteroids at doses of <3 drops a day is associated with a lower risk of cataract development relative to eyes receiving higher doses.[29]

Cataract surgery in children with uveitis is very challenging. Pre-existing complications, such as posterior synechiae and the presence of pupillary membrane make the access to the lens and the implantation harder.[30]

The standard of care among most uveitis specialists to minimize post-surgical complications, relies on the importance of controlling the inflammation, at least 3 months prior to cataract surgery.[31]

IOL implantation in JIA-associated uveitis has been a matter of debate. Historically, aphakia is considered a better option in cases with bilateral cataracts, while IOL implantation is a more feasible option in the cases of a unilateral cataract.[32]

Postoperative posterior capsular opacification (PCO) in children with JIA-associated uveitis is a very frequent complication that requires special attention to prevent amblyopia.[33]

Children with JIA-associated uveitis appear to be at a higher risk of complications than those with other forms of uveitis for developing cataracts.[34] Foster and Barrett found that, even with aggressive corticosteroid therapy treatment, there is no relationship between the development of complications and the course of a patient’s arthritis.

Particularly devastating and rare complication is the development of ciliary membranes, which can place traction on the ciliary body, leading to its detachment. Uveitis associated with JIA can also lead to ciliary body atrophy with hypotony, even in the absence of tractional detachment, presumably through the effects of chronic inflammation. Ultrasonographic biomicroscopy is an important technique for evaluating the ciliary body and identifying ciliary membranes, but may be difficult to perform in young children. [12]

One must also consider the risks associated with treatment. Complications of systemic corticosteroid therapy in children include growth retardation, weight gain, pancreatitis, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, cataracts, and ocular hypertension. The high morbidity rate associated with corticosteroid therapy mandates the use of steroid sparing IMT at an earlier stage.[35]

Prognosis

Risk factors have been identified which are associated with a worse prognosis and development of complications.[36]

- Male gender

- Young age at onset of uveitis

- Short duration between onset of arthritis and the development of uveitis

- Presence of synechiae at first ophthalmologist visit

A good control of the inflammation and a multi-disciplinary approach are key to improve the prognosis in the course of the disease.[37]

Additional Resources

- Porter D, Janigian RH. Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis Uveitis. American Academy of Ophthalmology. EyeSmart/Eye health. https://www.aao.org/eye-health/diseases/juvenile-idiopathic-arthritis-uveitis. Accessed March 14, 2019.

- https://aapos.org/

- https://www.rheumatology.org/

- https://www.aao.org/

- http://www.blindness.org/

References

- ↑ American Academy of Ophthalmology. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis. https://www.aao.org/image/juvenile-idiopathic-arthritis Accessed June 28, 2019.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Jabs DA, Nussenblatt RB, Rosenbaum JT; Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Working Group.. Standardization of uveitis nomenclature for reporting clinical data. Results of the First International Workshop. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005 Sep;140(3):509-16. Review. PubMed PMID: 16196117.

- ↑ Smith JA, Mackensen F, Sen HN, Leigh JF, Watkins AS, Pyatetsky D, Tessler HH, Nussenblatt RB, Rosenbaum JT, Reed GF, Vitale S, Smith JR, Goldstein DA. Epidemiology and course of disease in childhood uveitis. Ophthalmology. 2009 Aug;116(8):1544-51, 1551.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.05.002. Erratum in: Ophthalmology. 2011 Aug;118(8):1494. PubMed PMID: 19651312; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2937251.

- ↑ Chia A, Lee V, Graham EM, Edelsten C. Factors related to severe uveitis at diag-nosis in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis in a screening program. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;135:757–62.

- ↑ Zeggini E, Packham J, Donn R, Wordsworth P, Hall A, Thomson W; BSPAR Study Group. Association of HLA-DRB1*13 with susceptibility to uveitis in juvenile idiopathic arthritis in two independent data sets. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2006 Aug;45(8):972-4.

- ↑ Gori S, Broglia AM, Ravelli A, Aramini L, di Fuccia G, Nicola CA, et al. Frequency and complications of chronic iridocyclitis in ANA-positive pauciarticular juvenile chronic arthritis. Int Ophthalmol. 1994;18:225–8.

- ↑ Cassidy J, Kivlin J, Lindsley C, Nocton J; Section on Rheumatology.; Section on Ophthalmology.. Ophthalmologic examinations in children with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Pediatrics. 2006 May;117(5):1843-5. PubMed PMID: 16651348.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Cassidy J, Kivlin J, Lindsley C, Nocton J; Section on Rheumatology.; Section on Ophthalmology.. Ophthalmologic examinations in children with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Pediatrics. 2006 May;117(5):1843-5. PubMed PMID: 16651348.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Kanski JJ. Juvenile arthritis and uveitis. Surv Ophthalmol. 1990;34:253–67

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Anesi SD, Foster CS. Importance of recognizing and preventing blindness from juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis. Arthritis Care Res.2012;64:653–7.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Heiligenhaus A, Michels H, Schumacher C, Kopp I, Neudorf U, Niehues T, Baus H, Becker M, Bertram B, Dannecker G, Deuter C, Foeldvari I, Frosch M, Ganser G, Gaubitz M, Gerdes G, Horneff G, Illhardt A, Mackensen F, Minden K, Pleyer U, Schneider M, Wagner N, Zierhut M; German Ophthalmological Society.; Society for Childhood and Adolescent Rheumatology.; German Society for Rheumatology.. Evidence-based, interdisciplinary guidelines for anti-inflammatory treatment of uveitis associated with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Rheumatol Int. 2012 May;32(5):1121-33. doi: 10.1007/s00296-011-2126-1. Epub 2011 Nov 15. Review. PubMed PMID: 22083610.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Holland GN, Stiehm ER. Special considerations in the evaluation and management of uveitis in children. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003 Jun;135(6):867-78. Review. PubMed PMID: 12788128.

- ↑ Sen ES, Dick AD, Ramanan AV. Uveitis associated with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2015;11(6):338–48. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2015.20.

- ↑ Basic and clinical science course, 2017-2018 (Vol. 6). (2017). San Francisco: American Academy of Ophthalmology. Volume 6 Pediatric ophthalmology and Strabismus

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Abu Samra K, Maghsoudlou A, Roohipoor R, Valdes-Navarro M, Lee S, Foster CS. Current Treatment Modalities of JIA-associated Uveitis and its Complications: Literature Review. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2016 Aug;24(4):431-9. doi: 10.3109/09273948.2015.1115878. Epub 2016 Jan 14. Review. PubMed PMID: 26765345.

- ↑ Angeles-Han ST, Ringold S, Beukelman T, Lovell D, Cuello CA, Becker ML,Colbert RA, Feldman BM, Holland GN, Ferguson PJ, Gewanter H, Guzman J, Horonjeff J, Nigrovic PA, Ombrello MJ, Passo MH, Stoll ML, Rabinovich CE, Sen HN, Schneider R, Halyabar O, Hays K, Shah AA, Sullivan N, Szymanski AM, Turgunbaev M, Turner A,Reston J. 2019 American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation Guideline for the Screening, Monitoring, and Treatment of Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis-Associated Uveitis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2019 un;71(6):703-716. doi: 10.1002/acr.23871. Epub 2019 Apr 25. PubMed PMID:31021540.

- ↑ Heiligenhaus A, Mingels A, Heinz C, et al. Methotrexate for uveitis associated with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: value and requirement for additional anti-inflammatory medication. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2007;17:743–748.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Paroli MP, Del Giudice E, Giovannetti F, Caccavale R, Paroli M. Management Strategies of Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis-Associated Chronic Anterior Uveitis: Current Perspectives. Clin Ophthalmol. 2022 May 28;16:1665-1673.

- ↑ Levy-Clarke G, Jabs DA, Read RW, et al. Expert panel recommendations for the use of anti-tumor necrosis factor biologic agents in patients with ocular inflammatory disorders. Ophthalmology. 2014;121:785–796.

- ↑ 1: Ramanan AV, Dick AD, Jones AP, Hughes DA, McKay A, Rosala-Hallas A, WilliamsonnPR, Hardwick B, Hickey H, Rainford N, Hickey G, Kolamunnage-Dona R, Culeddu G,Plumpton C, Wood E, Compeyrot-Lacassagne S, Woo P, Edelsten C, Beresford MW. Adalimumab in combination with methotrexate for refractory uveitis associated with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a RCT. Health Technol Assess. 2019 Apr;23(15):1-140. doi: 10.3310/hta23150. PubMed PMID: 31033434; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6511891.

- ↑ Cecchin V, Zannin ME, Ferrari D, Pontikaki I, Miserocchi E, Paroli MP, Bracaglia C, Marafon DP, Pastore S, Parentin F, Simonini G, De Libero C, Falcini F, Petaccia A, Filocamo G, De Marco R, La Torre F, Guerriero S, Martino S, Comacchio F, Muratore V, Martini G, Vittadello F, Zulian F. Longterm Safety and Efficacy of Adalimumab and Infliximab for Uveitis Associated with Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2018 Aug;45(8):1167-1172.

- ↑ Angeles-Han ST, Ringold S, Beukelman T, Lovell D, Cuello CA, Becker ML, Colbert RA, Feldman BM, Holland GN, Ferguson PJ, Gewanter H, Guzman J, Horonjeff J, Nigrovic PA, Ombrello MJ, Passo MH, Stoll ML, Rabinovich CE, Sen HN, Schneider R, Halyabar O, Hays K, Shah AA, Sullivan N, Szymanski AM, Turgunbaev M, Turner A, Reston J. 2019 American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation Guideline for the Screening, Monitoring, and Treatment of Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis-Associated Uveitis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2019 Jun;71(6):703-716.

- ↑ Cantarini L, Simonini G, Frediani B, Pagnini I, Galeazzi M, Cimaz R. Treatment strategies for childhood noninfectious chronic uveitis: an update. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2012;21:1–6. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2012.636350. [PubMed]

- ↑ Grajewski RS, Zurek-Imhoff B, Roesel M, Heinz C, Heiligenhaus A. Favourable outcome after cataract surgery with IOL implantation in uveitis associated with juvenile idiopathic arthritis.. Acta Ophthalmol. 2012 Nov; 90(7):657-62.

- ↑ Magli A, Forte R, Rombetto L, Alessio M. Cataract management in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: simultaneous versus secondary intraocular lens implantation. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2014 Apr; 22(2):133-7.

- ↑ Terrada C, Julian K, Cassoux N, et al. Cataract surgery with primary intraocular lens implantation in children with uveitis: long-term outcomes. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2011;37:1977–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2011.05.037.

- ↑ Quinones K, Cervantes-Castaneda RA, Hynes AY, Daoud YJ, Foster CS. Outcomes of cataract surgery in children with chronic uveitis. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2009;35:725–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2008.12.014.

- ↑ Phatak S, Lowder C, Pavesio C. Controversies in intraocular lens implantation in pediatric uveitis. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2016 Dec;6(1):12. doi: 10.1186/s12348-016-0079-y. Epub 2016 Mar 24. Review. PubMed PMID: 27009616; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4805676.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Thorne JE, Woreta F, Kedhar SR, et al. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis: incidence of ocular complications and visual acuity loss. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143:840–846.

- ↑ Lam LA, Lowder CY, Baerveldt G, et al. Surgical management of cataracts in children with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis-associated uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;135:772–778.

- ↑ Murthy SI, Pappuru RR, Latha KM, et al. Surgical management in patient with uveitis. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2013;61:284–290.

- ↑ BenEzra D, Cohen E. Cataract surgery in children with chronic uveitis. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:1255–1260.

- ↑ Lundvall A, Zetterström C. Cataract extraction and intraocular lens implantation in children with uveitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000;84:791–793.

- ↑ Foster CS, Barrett F. Cataract development and cataract surgery in patients with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis-associated iridocyclitis. Ophthalmology. 1993 Jun;100(6):809-17. PubMed PMID: 8510892.

- ↑ Vitale A, Kump LI, Foster CS. Uveitis affecting infants and children. In: Harnett ME, ed. Pediatric Retina. 2nd edn. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2013.

- ↑ Angeles-Han ST, Yeh S, Vogler LB. Updates on the risk markers and outcomes of severe juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis. Int J Clin Rheumtol. 2013 Feb 1; 8(1).

- ↑ Tappeiner C, Klotsche J, Schenck S, Niewerth M, Minden K, Heiligenhaus A. Temporal change in prevalence and complications of uveitis associated with juvenile idiopathic arthritis:data from a cross-sectional analysis of a prospective nationwide study. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2015 Nov-Dec; 33(6):936-44.