Syphilitic Uveitis

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Syphilis is an infectious disease caused by Treponema Pallidum and is most commonly spread through sexual transmission. Syphilitic uveitis is the most common ocular manifestation and is a potentially blinding disease.

Brief History

Syphilis was first reported in Europe in the 15th century. There was rapid spread throughout Europe that was associated with the French invasion of Italy in 1494. The origin of syphilis has been well debated for over 500 years. Due to the temporal relation with Christopher Columbus’s voyage in 1492, many theorized the disease was brought to Europe by Columbus and his crew – the “Columbian Hypothesis.” Others theorized the disease was already present in the Old World before the 1490’s and the emergence of the disease in the 15th century was attributed to increased virulence and medical recognition – the “Pre-Columbian Hypothesis.” It is a debate that still continues today but an extensive review published by Harper et al. in 2011 supports the Columbian Hypothesis.

Timeline of Syphilis in the United States

- 1905, Treponema pallidum was first described by Schaudin and Hoffin as the causative bacteria of syphilis. They demonstrated spirochetes in Giema stained smears from syphilitic lesions.

- 1943: first reported cure with penicillin

- 1947: incidence of primary and secondary syphilis was 66.4 cases/100,000

- 1956: rates decline to 3.9 cases/100,000

- 1999: introduction of the National Plan to Eliminate Syphilis from the United States announced by the United States Surgeon General

- 2000: lowest ever recorded rate of 2.1 cases/100,000 (approximately 5,979 cases in year 2000)

- 2000-2012: steady increase with incidence exceeding 55,000 new cases a year

Risk Factors and At-Risk Populations

- Men who have sex with men (MSM)

- HIV co-infection

- Unprotected sex

Diagnosis

Syphilis is known as the Great Imitator as systemic manifestations vary. Ocular manifestations can affect any part of the eye, with syphilitic uveitis being the most common.

History

Any patient with intraocular inflammation (uveitis) should have a thorough history and review of systems. Information or risk factors that may suggest syphilis include a history of unprotected sex, recent STDs or HIV infection, MSM and substance abuse.

Physical examination

Syphilis can affect many parts of the body. Most common physical exam findings include:

- Skin Rash

- Palms and Sole maculopapular rash

- Genital and Perianal chancres

- Lymph Node Swelling

- Oral Cavity gummas

Ocular Symptoms

Due to the varying degrees of presentation patients may complain of blurry vision, floaters, light sensitivity, double vision, eye pain, and foreign body sensation

Clinical Diagnosis and Ocular Findings

| Anatomic Location | Ocular Findings |

|---|---|

| Conjunctiva | Mucous Patches, Papillary Conjunctivitis, Graulomatous Conjunctivitis |

| Sclera | Episcleritis and Scleritis |

| Cornea | Stromal Keratitis, marginal corneal infiltrates, Keratic precipitates |

| Lens | Congenital Cataract, Uveitic cataract |

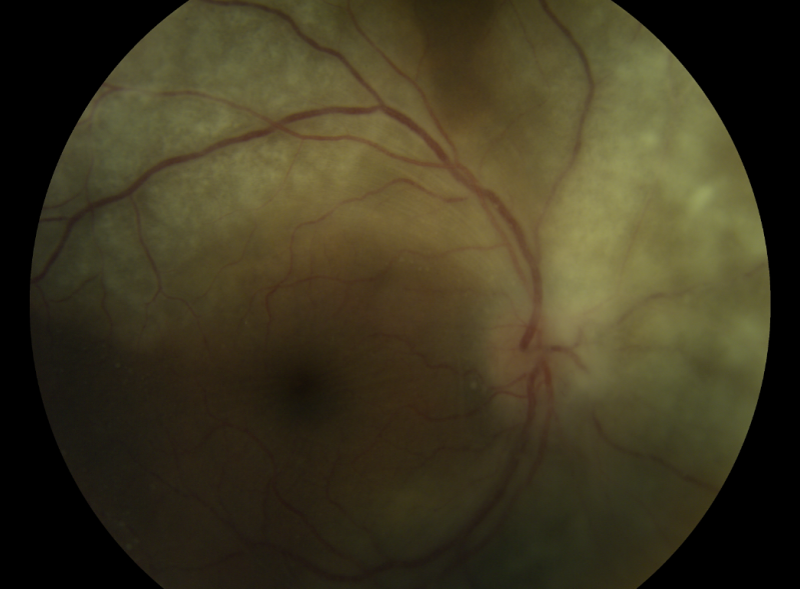

| Uveal Tract | Iritis, iridocyclitis, iris nodules, multifocal choroiditis, Posterior Placoid chorioretintis (typical), round viteous floaters just in front of the retina |

| Retina/RPE | Retinal vasculitis, RPE mottling, necrotizing retinitis, macular edema, retinochoroiditis, serous retinal detachment, rhegmatogenous retinal detachment, tractional retinal detachment |

| Optic Nerve | Disc edema and atrophy |

| Pupils | Argyll Robertson Pupil |

| Cranial Nerve and Brainstem | Extraocular motility deficit |

Images of posterior placoid chorioretinitis are available at https://imagebank.asrs.org/discover-new/files/1/25?q=Posterior%20Placoid%20Chorioretinitis

Testing for Suspected Syphilis

Serologic Tests

Serologic testing is the mainstay for diagnosis of ocular syphilis

Nontreponemal Tests (NTT)

- Measures antibodies against lipoidal antigens released by damaged host cells and possibly spirochetes

- Examples: RPR (rapid plasma reagin), VDRL (venereal disease research laboratory)

- Most useful test to track active disease and treatment efficacy

Treponemal Tests (TT)

- Measures antibodies against Treponema pallidum proteins

- Examples: EIA (enzyme immunoassay), FTA-ABS (Fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption), TPPA (T pallidum particle agglutination), TPHA (Treponema pallidum hemagglutination), CIA (chemiluminescence immunoassay)

- Stays positive for life

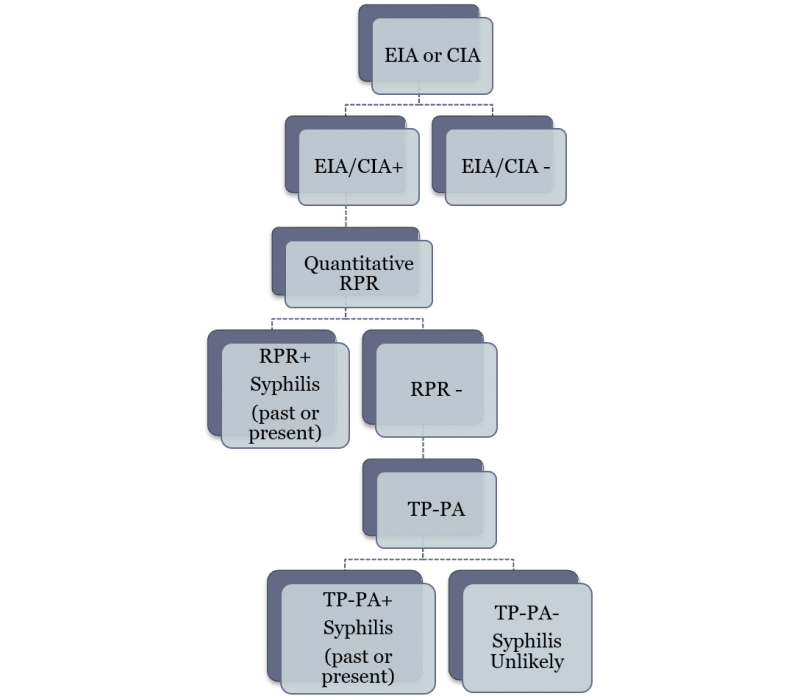

CDC recommendations for Syphilis Testing and Management

Reverse Sequence Testing

The CDC recommended testing algorithm for syphilis is shown. The algorithm starts with a highly sensitive but non specific immunoassay for treponemal antibodies. If the test is negative, syphilis is ruled out. If the test is positive then a non-treponemal test is performed. A positive non-treponemal test (RPR) is diagnostic of syphilis. A negative RPR following a positive EIA is a discordant test result. The negative RPR must be confirmed by a different treponemal test, the TP-PA, which is both sensitive and specific.

Other Tests

Other tests like Polymerase Chain Reaction and Immunoblot are being investigated for application in the diagnosis of ocular syphilis.

Molecular diagnostics involving the assessment of levels of cytokines and biomarkers for diagnostic purposes are being studied.[1]

Management and other considerations

- Treatment is the same as neurosyphilis: 10-14 day course of systemic antibiotics.

- All patients testing positive for syphilis should be tested for HIV due to the high rate of co-infection.

- All patients should undergo lumbar puncture and CSF analysis.

- Treatment should not be delayed while waiting for lumbar puncture.

Medical therapy

- IV Penicillin G 24 million units daily 10-14 day course or IM Procaine Penicillin 2.4 million units daily and Probenicid 2 grams daily

- Alternative therapeutic regimens including Ceftriaxone or Doxycycline have been attempted in patients who cannot be given Penicillin, albeit with varying success rates.

- Adjunctive Therapy:

- Topical steroids

- Oral steroids: useful to decrease inflammatory reaction (Jarisch–Herxheimer reaction) but there is no agreement on if and when to initiate. Those who utilize systemic steroids suggest starting with 40mg daily 2-3 days after initiation of systemic antibiotics. Oral steroid should not be started without proper antimicrobial coverage as it may worsen the disease (https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s12348-018-0164-5).

Medical follow up

- Repeat lumbar puncture indicated at 6 months post-treatment if initial CSF VDRL is positive.

- Persistent ocular inflammation despite full treatment course of antibiotics and oral corticosteroids may indicate treatment failure though this is rare. Consultation with infectious disease specialist is recommended to determine need for re-hospitalization and repeat systemic antibiotics.

- Titers are expected to decrease 4 fold after successful treatment.

Prognosis

The CDC has reported several cases of blindness related to syphilitic uveitis; however, prompt diagnosis and management with antibiotics leads to good visual acuity outcomes.

References

- ↑ Queiroz R de P, Smit DP, Peters RPH, Vasconcelos-Santos DV. Double Trouble: Challenges in the Diagnosis and Management of Ocular Syphilis in HIV-infected Individuals. Ocular Immunology and Inflammation. Published online July 13, 2020:1-9. doi:10.1080/09273948.2020.1772839

- Aldave, A.J., J.A. King, and E.T. Cunningham, Jr., Ocular syphilis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol, 2001. 12(6): p. 433-41.

- Amaratunge, B.C., J.E. Camuglia, and A.J. Hall, Syphilitic uveitis: a review of clinical manifestations and treatment outcomes of syphilitic uveitis in human immunodeficiency virus-positive and negative patients. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol, 2010. 38(1): p. 68-74.

- Butler, N.J. and J.E. Thorne, Current status of HIV infection and ocular disease. Curr Opin Ophthalmol, 2012. 23(6): p. 517-22.

- Chao, J.R., et al., Syphilis: reemergence of an old adversary. Ophthalmology, 2006. 113(11): p. 2074-9.

- Davis, J.L., Ocular syphilis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol, 2014. 25(6): p. 513-8.

- Gaudio, P.A., Update on ocular syphilis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol, 2006. 17(6): p. 562-6.

- Harper, K.N., et al., The origin and antiquity of syphilis revisited: an appraisal of Old World pre-Columbian evidence for treponemal infection. Am J Phys Anthropol, 2011. 146 Suppl 53: p. 99-133.

- Hughes, E.H., et al., Syphilitic retinitis and uveitis in HIV-positive adults. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol, 2010. 38(9): p. 851-6.

- Kiss, S., F.M. Damico, and L.H. Young, Ocular manifestations and treatment of syphilis. Semin Ophthalmol, 2005. 20(3): p. 161-7.

- Mathew, R.G., B.T. Goh, and M.C. Westcott, British Ocular Syphilis Study (BOSS): 2-year national surveillance study of intraocular inflammation secondary to ocular syphilis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 2014. 55(8): p. 5394-400.

- Tampa, M., et al., Brief history of syphilis. J Med Life, 2014. 7(1): p. 4-10.

- Woolston, S., et al., A Cluster of Ocular Syphilis Cases - Seattle, Washington, and San Francisco, California, 2014-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 2015. 64(40): p. 1150-1.