Idiopathic Retinitis, Vasculitis, Aneurysms, and Neuroretinitis (IRVAN)

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

This article presents a comprehensive review of a rare syndrome with distinctive retinal findings. Idiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysms, and neuroretinitis or IRVAN syndrome was first described in 1995 although case reports have been published since the 70s. This article is dedicated to all readers, especially our patients, who do not have easily access to scientific literature. The latest technique to study this disease, optical coherence tomography angiography of the retina, will be available for very first time to Eye Wiki users.

Disease Entity

Idiopathic Retinal Vasculitis, Aneurysms and Neuro-retinitis ( Chang et al )[1] and Idiopathic Retinitis, Vasculitis, Aneurysms, and Neuroretinitis ( Samuel et al )[2] are synonyms for IRVAN syndrome.

IRVAN is a subtype of retinal vasculitis. As such, it is recognized by the following codes as per the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) nomenclature[3]:

ICD-9 ICD 9 Data

362.18 Retinal Vasculitis

ICD-10 ICD 10 Data

H35.061 Retinal Vasculitis, right eye

H35.062 Retinal Vasculitis, left eye

H35.063 Retinal Vasculitis, bilateral

H35.069 Retinal Vasculitis, unspecified eye

External Links

Disease

Idiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysms, and neuroretinitis (IRVAN) syndrome is a rare clinical entity of unknown etiology. IRVAN syndrome is one of the contributions to Ophthalmology of J. Donald M. Gass, MD [4]( Figure 1 )

Etiology

Unknown.[5] Some authors[6] have speculated an association with positive P-ANCA s (Perinuclear AntiNeutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibodies) systemic vasculitis[7] and antiphospholipid syndrome[8].

Risk Factors

Slight female preponderance[1]. There is no race predilection[9]. Young or middle-aged people mainly affected[10].

Stages

Samuel et al proposed a new staging system in 2006 [2]:

- Stage 1 : Macroaneurysms, exudation, neuroretinitis, retinal vasculitis.

- Stage 2 : Capillary nonperfusion (angiographic evidence).

- Stage 3 : Posterior segment neovascularization of disc or elsewhere and/or vitreous hemorrhage.

- Stage 4 : Anterior segment neovascularization (rubeosis iridis).

- Stage 5 : Neovascular glaucoma.

Pathophysiology

Inflammation appears to be integral to IRVAN. It is possible that the inflammation damages the retinal arteries in a way that promotes aneurysmal dilations. Interestingly, the aneurysms in IRVAN appear to occur primarily in the first several orders of the retinal arteries, and aneurysms are not seen anterior to the equator. Although no histopathology of IRVAN is available, it is interesting to note that the muscular wall of the retinal arterioles continues to the equator as well. Perhaps inflammatory-driven damage to the retinal arteriolar wall induces the abnormal dilations seen in IRVAN. At present, there is no apparent cause for IRVAN, but an immunopathogenic cause may be the inciting event.[11]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of idiopathic retinitis, vasculitis, aneurysms, and neuroretinitis (IRVAN) is based on a constellation of clinical features. Three major criteria (retinal vasculitis, aneurysmal dilations at arterial bifurcations, and neuroretinitis) and 3 minor criteria (peripheral capillary nonperfusion, retinal neovascularization, and macular exudation) are used to diagnose IRVAN.[1][5]

Patients with IRVAN usually present with decreased visual acuity in one or both eyes[12]. They may have a variable number of cells in the anterior chamber and the vitreous.

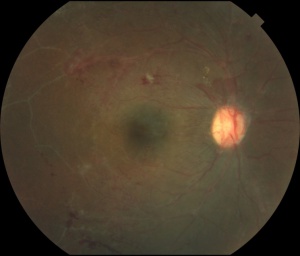

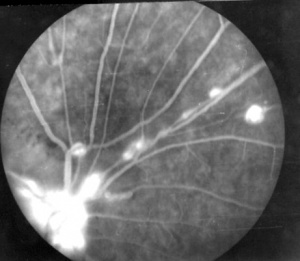

Macroaneurysms are a sine qua non condition to diagnosis of IRVAN syndrome[9]. The retinal arterioles have multiple aneurysmal dilatations extending through the first several orders of arterial branching until mid-periphery. The aneurysms are commonly found on the optic nerve, a site where typical senile retinal macroaneurysms are not. The aneurysms are typically found at branching points of the arteries, and may be fusiform, Y-shaped, or spheroid in shape. In segments between the aneurysms the retinal arteries frequently show marked caliber variations. Arterial aneurysms clinically resemble multiple and consecutive "knots of a cord" ( Figure 2 )

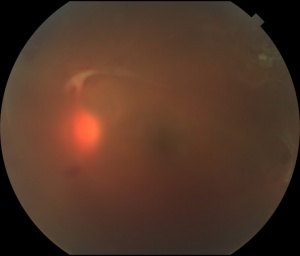

Disc neovascularization may be observed in severe and advanced cases of IRVAN, with peripheral capillary dropout. Vitreous hemorrhage can result from retinal neovascularization. Non-complicated cases may have a slight swelling of the optic nerve head, highlighted in late phases of fluorescein angiography. Some authors think there is no true neuroretinitis, and leakage occurs from the aneurysms on the optic nerve head and periarterial lipid exudation results from retinal artery aneurysms.

Retinal vascular sheathing may occur, but it is not a prominent feature of the disorder in most patients. In the retinal periphery, there is a variable amount of retinal nonperfusion, with obliteration of the arteries, veins, and retinal capillaries. In the perfused area bordering the peripheral areas of nonperfusion, the retinal veins may show abnormal caliber alterations. If the ischemic load of the nonperfused retina reaches a critical level, retinal and iris neovascularization may develop. Interestingly , neo-vessels may sometimes reproduce arterial macroaneurysms seen in the retinal vasculature ( Richard F Spaide MD, personal communication ). In severely affected individuals, vitreous hemorrhage and neovascular glaucoma have developed.[13]

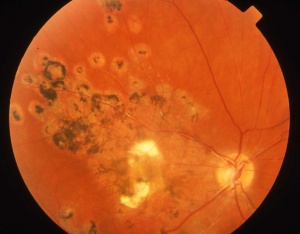

Although lipid deposition is not common in most patients with uveitis, patients with IRVAN frequently have marked intraretinal lipid deposition. This lipid is usually found in the peripapillary region and may extend into the macula leaving a macular star or massive lipid accumulation . The lipid is generally found near the greatest concentration of aneurysms ( peripapillary location and along the arcades ) . The retina in these areas is commonly edematous and may be detached by exudative fluid. As time goes by, a fibrous grayish macular scar may develop as a legacy of long-standing exudation in the macula.[10]

History

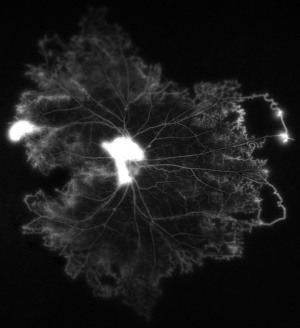

In 1973, Karel I. et al. published one case correspondent to a 15 year-old girl, in a series of pediatric uveitis, who matched the typical findings showed much later in IRVAN’s syndrome.[14] In 1978, Verdaguer T. presented, at a national conference, two otherwise healthy subjects who presented multiple arterial aneurysms from optic nerve up to mid-periphery ( Figure 3 ). He described a 20 year-old female with numerous aneurysmal dilatations within the arterial tree and marked lipid accumulation in both maculas and a 32 year-old man who had a gliotic macular scar secondary to a long-standing exudation in his macula. This author certified the leakage from retinal aneurysms by fluorescein angiography and stated that “ this disease as an independent entity” [15]( Figure 4 )

In 1983, Kincaid and Schatz described a bilateral inflammatory eye disease associated with multiple retinal aneurysms[16]. Since then, only few reports [17][18]were added to the scientific literature with no evidence of any concomitant systemic disease [19]and, relatively, a good visual prognosis.

In 1995 , Chang et al [1]first described the largest series of ten patients, ranging from 7 through 44 years of age, who met the criteria for a new retinal syndrome ( presence of retinal vasculitis, multiple aneurysms, and neuroretinitis not associated with any systemic abnormalities ) So, the authors proposed the acronym IRVAN to highlight the most prominent clinical features of this syndrome ( Idiopathic Retinal Vasculitis, Aneurysms and Neuro-retinitis ) . This report was presented at the ARVO Annual Meeting and published by the Retinal Vasculitis Study Group led by J. Donald M.Gass.

In 2007, Samuel et al[2] made new observations on the follow up of these originally described patients and added twelve more subjects. Although IRVAN syndrome was believed to be a benign condition, they found and clarified that it can lead to a severe visual loss.

They also proposed a staging classification based on retinal ischemia status and established that an early panretinal laser photocoagulation should be considered when angiographic evidence of retinal nonperfusion is present. The latter was considered the first line of treatment until now. IRVAN word stood for Idiopathic Retinitis, Vasculitis, Aneurysms, and Neuroretinitis, a small variation from the original acronym.

Finally, between 2009 through 2011 , Soheilian [6]and Nourinia[7] have found some patients affected by IRVAN syndrome, that have positive perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody levels ( P-ANCA ) on systemic workup . Thus, IRVAN syndrome may be retinal manifestation of a P-ANCA associated systemic vasculitis.

Signs

- Multiple postequatorial arterial aneurysms in the retina and optic disc head.

- Peripapillary lipid exudation associated with macroaneurysms and retinal vasculitis.

- Retinal hemorrhages in posterior pole.

- Peripheral capillary nonperfusion

- Retinal vascular sheathing

- Swelling of the optic nerve

- Retinal neovascularization

- Optic disc neovascularization

Symptoms

Asymptomatic

Patient may not complain about loss of vision in spite of having a severe disease if it does not affect the macula at the initial presentation ( Figure 5 )

Non specific symptoms

For instance , multiple visits for a change of glasses due to blurred vision.

Symptoms of Retinal Vasculitis

Clinical Diagnosis

Patients with IRVAN are , sometimes, over investigated for systemic causes of retinal disease. However, IRVAN seems to produce only ophthalmic manifestations, with general workup being mostly unremarkable. Retinal imaging is a key element for a rapid diagnosis of IRVAN[20], and a multimodal imaging approach is recommended when this syndrome is suspected, to collect all possible diagnostic criteria. Dye-mediated angiographies ( fluorescein and indocyanine green[21] ) remain the standard imaging modalities for confirming clinical diagnosis of IRVAN.[22]

Diagnostic procedures

Fluorescein angiography

Fluorescein angiography highlights the arteriolar abnormalities. The aneurysms are more evident and the alterations in arteriolar caliber are more obvious. Leakage of fluorescein from the aneurysms is apparent. Patients with IRVAN usually have optic nerve head staining. Of course, disc and/or retinal neovascularization show marked fluorescein leakage. The areas of peripheral non- perfusion are easier to appreciate with fluorescein angiography, especially wide-field fluorescein angiography.[23][24]

Indocyanine green angiography

The aneurysmal dilatations showed uniform staining. No abnormalities were seen in the choroidal vessels; in particular, no aneurysms of the choroidal vessels have been observed. For example, the retinal abnormalities and macroaneurysms in IRVAN are more clearly imaged with ICG angiography, especially at the very late stages, but the leakage, ischemia, and retinal neovascularization are still best delineated with FA.[25]

OCT

It is useful to assess macular edema , vitreoretinal traction over both the macula and optic nerve head , neovascular tufts in posterior pole and epiretinal membrane , as an example[26] [27]

OCT-A

OCT-A is a dye-free, noncontact modality to image the eye. It is a noninvasive imaging modality that provides three-dimensional images of the retina and choroidal microvasculature in vivo.

OCT-A has its clinical shortcomings and is less useful for identification of retinal vasculitis

- It doesn’t show leakage

- Patients with poor fixation are difficult to image effectively.

- Opaque media such as vitreous hemorrhage blocks OCT signal and decrease the quality of the angiography.

- Although widefield OCT-A will allow for imaging of the vascular layers, likely out to the mid-periphery and vortex veins, ultra-wide field FA will still provide information about retinal capillary perfusion out to the ora serrata.

Laboratory test

There are no specific tests for diagnosing IRVAN.

Differential diagnosis

At presentation, the physician must distinguish clinical elements of this interesting disease : arterial macroaneurysms , lipid exudation , retinal periphery capillary dropouts and neovascularization. [5]The syndrome’s striking ophthalmoscopic picture is not shared by any other disease.[9] However, four principal conditions may have similar initial presentation and should be excluded:

- The first is idiopathic retinal vasculitis[28], if the aneurysmal dilations are not noticed. Careful ophthalmoscopic and fluorescein angiographic examination should reveal any aneurysmal dilations, if present.

- The second is senile retinal arterial macroaneurysm. This acquired macroaneurysm is usually found in older patients with a history of high blood pressure and/or cardiovascular diseases[9][5]. It usually is single, mostly unilateral, located temporal to the optic nerve along the midsegment of an artery, and associated with hemorrhage. Although there may be capillary telangiectasis surrounding the macroaneurysm, there is no peripheral nonperfusion or signs of inflammation. Patients with IRVAN are otherwise healthy young people and arterial macroaneurysms are bilateral and multiple.

- The third element in the differential diagnosis is Coats´ disease[5]. Patients with Coats’ disease have generally a unilateral presentation with no signs of intraocular inflammation. The aneurysms of Coats’ disease usually involve more than one element of the vascular circuit and may involve the arteries, capillaries, and veins. The aneurysms in Coats’ disease do not involve arterial bifurcations and they are observed in the mid and far periphery usually surrounded by abundant circinate lipid exudation. Finally , peripheral telangiectasias are irregular in shape compared to aneurysms.

- The fourth condition is Eales´ disease.[9] Peripheral retina non-perfusion with periphlebitis is almost always present with retinal neovascularization. Nevertheless, in Eales' disease, typical fusiform or "tied-knot " arterial aneurysms and exudation are generally not common.

Management

Currently , retinal laser photocoagulation and the use of intravitreal injections of anti-vascular endothelial grow factor antibodies (anti-VEGF ) are considered within the first line of treatment. Interestingly, arterial macroaneurysms may regress or vanish after treatment or during follow-up.[29][30][31][32]

General treatment

- Observation : Basha et al [33]have published a pediatric case with IRVAN , one eye treated and the fellow eye untreated. A long-term follow-up demonstrated that observation is a consideration in IRVAN syndrome if the vision remains good with hard exudation.[34][35]

Medical therapy

Corticosteroids

Patients affected with IRVAN have been treated with corticosteroids in an attempt to reduce any inflammatory worsening of their ophthalmoscopic appearance. Unfortunately, corticosteroids have not been particularly useful. Although corticosteroids undoubtedly decrease inflammation, much of the morbidity of IRVAN results from chronic secondary changes such as persistent leakage from the aneurysms and vitreous hemorrhage from the neovascularization.

- Systemic use: Prednisone 1mg/kg daily or intravenous[36]

- Intravitreal injections: Triamcinolone Acetate and Dexamethasone implant to treat chronic macular edema[37]

Anti - VEGF intravitreal injections

Pegaptanib ( MACUGEN )[38] , Bevacizumab ( AVASTIN ) [39], Ranibizumab ( LUCENTIS ) [40] and Aflibercept ( EYLEA ) have been used for treating IRVAN syndrome in patients with macular edema , retinal ischemia and neovascularization of the eye.

Immunosuppressive drugs

Cheema et al [41] and Samalia et al [42]showed improvement in two patients treated with infliximab, an anti-TNF. TNFα might be a causative factor in mediating inflammation and causing tissue destruction in IRVAN patients. Saatci et al used oral azathioprine as an adjuvant in a patient with IRVAN.[43] Ameratunga et al used monthly cycles of pulsed intravenous methylprednisolone 1 gm on 3 consecutive days for 7 months along with mycophenolate mofetil and oral prednisone 10 mg daily.[44]

Medical follow up

Follow-up depends on the clinical condition. IRVAN patients should be followed at least every 3 months until stabilization.[45]

Surgery

Thermal Focal Laser and Peripheral Retinal Photocoagulation

Focal laser treatment to the macroaneurysms may decrease the amount of lipid exudation, but carries the risk of causing focal occlusion of the retinal arteriole, thus its use is controversial[46]. Laser spots may be applied surrounding macroaneurysms areas but never directly. Laser-induced arteriolar occlusion has caused in some patients to lose substantial visual acuity[47].Panretinal photocoagulation to the peripheral areas of nonperfusion is performed in patients even before retinal / optic disc neovascularization appear. Several laser sessions may be required for each eye. The aim of this treatment is causing a regression of the new vessels. Some patients with substantial amounts of vitreous hemorrhage have required vitrectomy and laser endophotocoagulation to treat bleeding areas of retinal neovascularization. Although retinal and vitreous hemorrhages occur from typical senile retinal arterial macroaneurysms, bleeding from the aneurysmal dilations of IRVAN is not common.

Peripheral cryotherapy

Some authors have used this procedure, especially when opaque media is present and peripheral laser treatment cannot be applied.

Pars Plana Vitrectomy

Indications:

- Nonclearing or recurrent vitreous hemorrhage, that prevents appropriate medical treatment (Figure 6.)

- Tractional retinal detachment, due to proliferative retinopathy, especially when the macula is threatened or involved. Severe cases may need lensectomy, core vitrectomy, separation of posterior hyaloid, peeling of epiretinal membranes and vitreous base for eliminating vitreoretinal traction and silicone oil for a long-term vitreous tamponade.

Surgical follow up

A regular follow up is needed for these patients and a long-term follow up is possible.[48] ( Figure 7 )

Complications

Anterior segment

Iris neovascularization , neovascular glaucoma[49] , blind eye , painful blind eye.

Posterior segment

Disc neovascularization , retinal neovascularization ( Figure 8 ) , vitreous hemorrhage, tractional retinal detachment , retinal artery occlusion.[50][51][52]

Prognosis

The prognosis is variable and largely dependent on the extent of retinal damage and related complications, including atrophic scarring and glaucoma[53].

Additional Resources

Organizations Supporting this Disease

- American Foundation for the Blind :1401 South Clark Street Suite 730 Arlington, VA 22202 Toll-free: 800-232-5463. Telephone: 212-502-7600, Fax: 888-545-8331 E-mail: info@aph.org, Website: http://www.afb.org/

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Chang TS, Aylward GW, Davis JL, et al. Idiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysms, and neuro-retinitis. Ophthalmology. 1995;102:1089–1097.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Samuel MA, Equi RA, Chang TS, et al. Idiopathic retinitis, vasculitis, aneurysms, and neuroretinitis (IRVAN): new observations and a proposed staging system. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:1526–1529.

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control (CDC). International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification(ICD-10-CM): FY 2017 version; 2017. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/icd/icd10cm.htm. Accessed November 23,2017.

- ↑ Flynn J, Clarkson J, Curtin V, Flynn Jr. H, Hurtes R, Smith J. J. Donald M Gass, MD : Festschrift Editorial. Am J Ophthalmol 2004;137,3:480-2.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Gass JD. Stereoscopic Atlas of Macular Diseases: Diagnosis and Treatment. 3rd ed. St Louis: Mosby; 1987.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Soheilian M, Nourinia R, Tavallali A, Peyman GA. Idiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysms, and neuroretinitis syndrome associated with positive perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (P-ANCA). Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2010;4:198–201.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Nourinia R, Montahai T, Amoohashemi N, Hassanpour H, Soheilian M.Idiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysms and neuroretinitis syndrome associated with positive perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2011;6:330–333.

- ↑ Kurz DE, Wang RC, Kurz PA. Idiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysms, and neuroretinitis in a patient with antiphospholipid syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130:257–258.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 In Spanish : Arévalo JF, Graue-Wiechers F, Quiroz-Mercado H, Rodríguez FJ, Wu L. Retina medica Temas selectos. 1st Edition.Caracas,Venezuela: AMOLCA;2007:338-42.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Agarwal A. Idiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysms, and neuroretinopathy (IRVAN). In: Gass’ Atlas of Macular Diseases. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders: 2012:534–538.

- ↑ Sanders M. Retinal arteritis, retinal vasculitis, and autoimmune retinal vasculitis. Eye (Lond). 1987;1:441–465.

- ↑ Moosavi M, Hosseini SM, Shoeibi N, Ansari-Astaneh MR. Unilateral idiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysms, and neuroretinitis (IRVAN) syndrome in a young female. J Curr Ophthalmol. 2015;27:63–66.

- ↑ Rouvas A, Nikita E, Markomichelakis N, Theodossiadis P, Pharmakakis N. Idiopathic retinal vasculitis, arteriolar macroaneurysms and neuroretinitis: clinical course and treatment. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2013;3:21.

- ↑ Karel I, Peleska M, Divisová G. Fluorescence angiography in retinal vasculitis in children’s uveitis. Ophthalmologica. 1973;166:251–264.

- ↑ In Spanish : Verdaguer T. J. Conferencia Charlin 1978 " Enfermedades vasculares de la retina y su tratamiento ". Arch Chil Oftalmol. 1978;35,1:35-62.

- ↑ Kincaid J, Schatz H. Bilateral retinal arteritis with multiple aneurysmal dilatations. Retina. 1983;3:171–178.

- ↑ Jampol LM, Isenberg SJ, Goldberg MF. Occlusive retinal arteriolitis with neovascularization. Am J Ophthalmol. 1978;81:583–589.

- ↑ Lewis RA, Norton EW, Gass JD. Acquired arterial macroaneurysms of the retina. Br J Ophthalmol. 1976;60:21–30.

- ↑ In French : Malan P, Ciurana AJ, Boudd C.Arterité rètinienne bilatèrale avec dilatations aneurysmales multiples. J Fr Ophthalmol 1986;9:23-28

- ↑ Pichi F, Ciardella AP. Imaging in the diagnosis and management of idiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysms, and neuroretinitis (IRVAN). Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2012;52:275–282.

- ↑ Yannuzzi L. Indocyanine green angiography : a perspective on use in clinical setting. Am J Ophthalmol 2011;151:745-751.

- ↑ Leder HA, Campbell JP, Sepah YJ, et al. Ultra-wide-field retinal imaging in the management of non-infectious retinal vasculitis. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2013;3:30.

- ↑ Yeshurun I, Recillas-Gispert C, Navarro-Lopez P, Arellanes-Garcia L, Cervantes-Coste G. Extensive dynamics in location, shape, and size of aneurysms in a patient with idiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysms, and neuroretinitis (IRVAN) syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;135(1):118–120.

- ↑ Meng PP, Lin CJ, Hsia NY, Lai CT, Bair H, Lin JM, Chen WL, Tsai YY. Use of Ultra-Widefield Fluorescein Angiography to Guide the Treatment to Idiopathic Retinal Vasculitis, Aneurysms, and Neuroretinitis-Case Report and Literature Review. Medicina (Kaunas). 2022 Oct 16;58(10):1467.

- ↑ Gharbiya M, Pantaleoni FC, Accorinti M, Pezzi PP. Indocyanine green angiography in a case of idiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysms and neuroretinitis. Eye 2000; 14: 655–659.

- ↑ Venkatesh P, Vashisht N, Garg S. Optical coherence tomographic features in idiopathic retinitis, vasculitis, aneurysms and neuroretinitis. J Ophthalmic Res. 2014;1:7–12.

- ↑ Banaee T, Hosseini SM.Optical Coherence Tomography Features in Idiopathic Retinal Vasculitis, Aneurysms and Neuroretinitis Syndrome. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2015 Apr-Jun;10(2):193-6.

- ↑ Gedik S, Yilmaz G, Akça S, Akova YA. An atypical case of idiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysms, and neuroretinitis (IRVAN) syndrome. Eye (Lond). 2005;19:469–471.

- ↑ Owens SL, Gregor ZJ. Vanishing retinal arterial aneurysms: a case report. Br J Ophthalmol. 1992;76:637–638.

- ↑ Sashihara H, Hayashi H, Oshima K. Regression of retinal arterial aneurysms in a case of idiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysms, and neuroretinitis (IRVAN). Retina. 1999;19:250–251.

- ↑ El-Asrar AM, Jestaneiah S, Al-Serhani AM. Regression of aneurysmal dilatations in a case of idiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysms and neuroretinitis (IRVAN) associated with allergic fungal sinusitis. Eye (Lond). 2004;18:197–201.

- ↑ Singh R, Sharma K, Agarwal A, et al. Vanishing retinal arterial aneurysms with anti-tubercular treatment in a patient with idiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysms and neuroretinitis. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2016;6:8.

- ↑ Basha M, Brown GC, Palombaro G, Shields CL, Shields JA. Management of IRVAN syndrome with observation. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2014 May 1;45.

- ↑ Krishnan R, Shah P, Thomas D. Subacute idiopathic vasculitis, aneurysms and neuroretinitis (IRVAN) in a child and review of paediatric cases of IRVAN revealing preserved capillary perfusion as a more common feature. Eye (Lond). 2015;29:145–151.

- ↑ DiLoreto DA Jr, Sadda SR. Idiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysms, and neuroretinitis (IRVAN) with preserved perfusion. Retina. 2003;23:554–557.

- ↑ Ishikawa F, Ohguro H, Sato S, Sato M, Yamazaki H, Nakazawa M.A case of idiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysm, and neuroretinitis effectively treated by steroid pulse therapy. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2006 Mar-Apr;50(2):181-5.

- ↑ Empeslidis T, Banerjee S, Vardarinos A, Konstas AG. Dexamethasone intravitreal implant for idiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysms, and neuroretinitis. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2013;23:757–760.

- ↑ Mitry D, Schmoll C, Hegde V, Borooah S, Singh J, Bennett H.Use of pegaptanib in the treatment of vitreous haemorrhage in idiopathic retinal vasculitis. Eye (Lond). 2008 Nov;22(11):1449-50.

- ↑ Akesbi J, Brousseaud FX, Adam R, Rodallec T, Nordmann JP. Intravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin) in idiopathic retinitis, vasculitis, aneurysms and neuroretinitis. Acta Ophthalmol. 2010;88:40–41.

- ↑ Karagiannis D, Soumplis V, Georgalas I, Kandarakis A. Ranibizumab for idiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysms, and neuroretinitis: favorable results. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2010;20(4):792–794.

- ↑ Cheema RA, Al-Askar E, Cheema HR. Infliximab therapy for idiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysm, and neuroretinitis syndrome. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2011;27:407–410.

- ↑ Samalia P, Sims J, Deva N. Idiopathic Retinal Vasculitis, Aneurysms and Neuroretinitis: Clinical Improvement with Infliximab. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2023 Feb;31(2):437-444.

- ↑ Saatci AO, Ayhan Z, Takeş O, Yaman A, Bajin FM. Single bilateral dexamethasone implant in addition to panretinal photocoagulation and oral azathioprine treatment in IRVAN syndrome. Case Rep Ophthalmol. 2015;6:56–62.

- ↑ Ameratunga R, Donaldson M. TREATMENT OF IDIOPATHIC RETINAL VASCULITIS, ANEURYSMS, AND NEURORETINITIS (IRVAN) WITH PHOTOCOAGULATION IN COMBINATION WITH SYSTEMIC IMMUNOSUPPRESSION. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2020 Fall;14(4):334-338.

- ↑ Tomita M, Matsubara T, Yamada H, et al. Long term follow up in a case of successfully treated idiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysms, and neuroretinitis (IRVAN). Br J Ophthalmol. 2004;88:302–303.

- ↑ Russell SR, Folk JC. Branch retinal artery occlusion after dye yellow photocoagulation of an arterial macroaneurysm. Am J Ophthalmol. 1987;104:186–187.

- ↑ Terrada C, Dethorey G, Ducos G, Lehoang P, Bodaghi B, Souied EH. Spontaneous branch artery occlusion in idiopathic retinitis, vasculitis, aneurysms, and neuroretinitis syndrome despite panretinal laser photocoagulation of widespread retina non perfusion. Acta Ophthalmol. 2011 Sep;89(6):e542-3.

- ↑ Xia Y, Su Y, Wong IH, Ma X, Hua R.Fluorescein photodiagnosis of idiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysms, and neuroretinitis (IRVAN) syndrome: A case report and long-term outcome of photocoagulation therapy. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2016 Dec;16:15-16.

- ↑ Sinha G, Nayak B, Gupta S, Gupta V.Bilateral neovascular glaucoma in idiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysms, and neuroretinitis syndrome. Can J Ophthalmol. 2016 Apr;51(2):e43-5.

- ↑ Parchand S, Bhalekar S, Gupta A, Singh R. Primary branch retinal artery occlusion in idiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysms, and neuroretinitis syndrome associated with hyperhomocystenemia. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2012;6:349–352.

- ↑ Venkatesh P, Verghese M, Davde M, Garg S. Primary vascular occlusion in IRVAN syndrome. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2006;14:195–196.

- ↑ Zacharia JA, Chin AT, Rebhun CB, Louzada RN, Adhi M, Cole ED, Moreira-Neto C, Waheed NK, Duker JS. Idiopathic Retinal Vasculitis, Aneurysms, and Neuroretinitis Syndrome Presenting With Branch Retinal Artery Occlusion. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2017 Nov 1;48(11):948-951.

- ↑ MacIver S, Bass SJ, Sherman J. Visual acuity recovery in a case of idiopathic retinal vasculitis aneurysms and neuroretinitis. Optom Vis Sci. 2012;89:E356–E363.