Abducens Nerve Palsy

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Strabismus/ocular misalignment

Disease

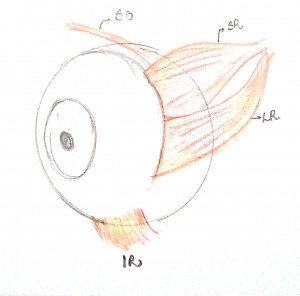

Abducens (sixth cranial) nerve palsy is the most common ocular motor paralysis in adults and the second-most common in children. The abducens nerve controls the lateral rectus muscle, which abducts the eye. Abducens nerve palsy causes an esotropia due to the unopposed action of the antagonistic medial rectus muscle. The affected eye turns medially and is unable to abduct properly. The esodeviation is incomitant, greater when the patient is looking toward the affected side and when fixating at distance versus at near.

Etiology

Damage or disruption to the abducens nerve anywhere along its long intracranial course can result in a palsy. The nerve begins at its nucleus in the dorsal pons and courses superiorly and then anteriorly before leaving the brainstem at the pontomedullary junction. It then travels along the skull base in the subarachnoid space, over the petrous apex of the temporal bone tethered in the Dorello canal (ie, an opening below the petroclinoid ligament), and through the cavernous sinus and superior orbital fissure, and then enters the orbit, traveling through the annulus of Zinn to reach the lateral rectus muscle. Potential etiologies of abducens nerve palsy are different in children and adults and depend on the anatomic location of damage.

In pediatrics

Congenital

Congenital palsies are relatively rare. They can be associated with birth trauma, developmental neuronal migration defects,[1] and neurological conditions such as hydrocephalus and cerebral palsy.

Acquired

Acquired abducens nerve palsies in childhood can be due to neoplasms, trauma, infection, inflammation, and idiopathic etiologies. Nontraumatic acquired sixth cranial nerve palsies may be due to benign recurrent sixth cranial nerve palsy, pontine gliomas, elevated or low intracranial pressure, and in rare cases, acute lymphoblastic leukemia.[2] Benign isolated abducens nerve palsy can occur in childhood during an episode of sinusitis,[2] or following an ear, throat, or viral infection. Rarely, isolated abducens nerve palsy can present in children with Kawasaki disease after IVIG therapy.[3]

Intracranial tumor

- Brainstem gliomas are one of the common tumors seen in the pediatric population, and more than 80% arise from the pons, with the peak age of onset between 5 and 8 years of age. Presenting symptoms include ataxia, disturbance of gait, and unilateral or bilateral abducens nerve palsy.

- Posterior fossa tumors, such as pontine gliomas, medulloblastomas, ependymomas, trigeminal schwannomas,[4] or cystic cerebellar astrocytomas can produce unilateral or bilateral abducens nerve palsies in children. Abducens nerve palsy can also present as a postoperative complication after resection of posterior fossa tumors in the pediatric population.

Trauma, secondary to open- or closed-head injuries

Trauma causes indirect pressure on the nerve, which is very susceptible to trauma as it passes over the apex of the petrous portion of the temporal bone to the cavernous sinus. In addition, traumatic abducens nerve palsy can occur secondary to bruising and/or hemorrhage, causing pressure on the nerve. Closed-head trauma may cause elevated intracranial pressure (ICP) and secondarily produce a nonlocalizing sixth nerve palsy.

Elevated or low intracranial pressure

Elevated intracranial pressure can cause stretching of the sixth cranial nerves, which are tethered in the Dorello canal. The same mechanism can explain the reason for the nonlocalizing sixth nerve palsy that can be seen with either elevated or reduced intracranial pressures.[5] Elevated intracranial pressure can occur secondary to a variety of different causes, including shunt failure, idiopathic intracranial hypertension, posterior fossa tumors, neurosurgical trauma, venous sinus thrombosis, meningitis, or Lyme disease.

Meningitis

Hanna and colleagues found abducens nerve palsy in 16.5% of patients with acute bacterial meningitis. Cranial nerve palsies in this setting tend to be multiple and bilateral.[6]

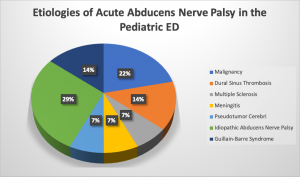

Based on an retrospective study of 14 patients admitted to Hacettepe University Children’s Hospital Pediatric Emergency Department between Jan 01, 2002 and December 31, 2012.[2]

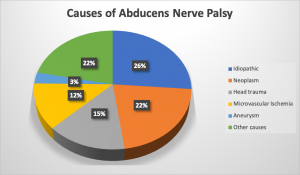

In adults

Microvascular ischemia

Trauma

Idiopathic

Less likely etiologies:

- Multiple sclerosis

- Neoplasm skull-base tumors (clivus meningioma, chordoma, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, metastasis) predominate in the adult population

- Stroke

- Sarcoidosis/vasculitis

- Increased intracranial pressure

- Giant cell arteritis

- Hypophosphatasia syndrome (with secondary clival thickening)[7]

- Gestational hypertension[8]

- Gradenigo syndrome[9]

- Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease[10]

- Syphilis[11]

- Poliomyelitis[11]

- Mastoiditis[11]

- COVID-19 [12]

Lesions causing abducens nerve palsy can also be classified by the location of the lesion.:

- Fascicular

- Demyelination, vascular disease, and metastatic tumors are likely causes of fascicular damage. Lesions in this area can cause Foville syndrome (damage to the pontine tegmentum), which is classified by partial sixth nerve palsy, ipsilateral facial weakness, loss of taste in the anterior portion of the tongue, ipsilateral Horner syndrome, ipsilateral facial sensory loss and ipsilateral peripheral deafness. Lesions in the fascicular area can also cause Millard-Gubler syndrome, which is a result of damage to the ventral pons and is characterized by sixth nerve palsy and contralateral hemiplegia; it may or may not also include ipsilateral facial paralysis.

- Peripheral

- Causes of peripheral nerve damage include closed head injury, compression, and bacterial infection of the inner ear. Localized compression can be caused by a primary pituitary tumor, craniopharyngioma, schwannoma,[13] or meningioma. Metastatic tumors and aneurysms involving the basilar artery can also cause an abducens nerve palsy.

Risk Factors

Inflammatory and microvascular conditions are risk factors for abducens nerve palsy. Other risk factors include multiple sclerosis, encephalitis, meningitis, cavernous sinus thrombosis, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, aneurysm, diabetes, arteriosclerosis, birth trauma, and neurosurgical intervention.[11]

Pathophysiology

Microvascular Ischemia Pathology

Due to the fact that microvascular ocular motor nerve palsies are usually self-limiting and not life-threatening, autopsies are usually not performed. Therefore, little is known about the pathophysiology of microvascular ocular nerve palsies. From the few patients that have presented with microvascular ocular motor nerve palsies and have been examined at autopsy, microscopic sections revealed the following: areas of extensive demyelination, fragmentation of the nerve sheath, and thickening and hyalinization of the blood vessels in the vasa nervorum.[14]

Primary Prevention

Preventable causes of abducens nerve palsy include microvascular conditions such as hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, aneurysm, diabetes, and arteriosclerosis; thus, the proper lifestyle changes, adherence to medication regimen, and regular follow-up visits with one’s primary care physician can foster prevention.

Diagnosis

History

The pattern of onset and associated symptoms can be very important in determining the etiology of an abducens nerve palsy. Sudden onset suggests a vascular etiology, while slowly progressive onset suggests a compressive etiology. Subacute onset suggests a demyelinating process.

Physical Examination

All patients with presumed abducens nerve palsy need a complete ophthalmologic examination, including visual acuity; binocular function and stereopsis; motility evaluation; strabismus measurements at near, distance, and in the cardinal positions of gaze; measurement of fusional amplitudes; cycloplegic refraction, and evaluation of ocular structures in the anterior and posterior segments. Precise assessment of ductions and versions, as well as precise orthoptic measurements in lateral positions of gaze, are helpful in determining incomitance associated with abducens nerve palsy. Slow saccadic velocity in side gaze may be present and is helpful with the diagnosis. In children, given that neoplasms and trauma are the most common etiologies of abducens nerve palsy, immediate and careful evaluations must be performed to rule out serious etiologies.[2] It is important to keep in mind the pseudo-restrictive effects of alternating monocular fixation and vergence when having both eyes open at the same time; therefore, each eye must be tested independently.[11]

Signs

The cardinal sign of abducens nerve palsy is esotropia of the affected eye due to unopposed action of the medial rectus muscle. The esotropia is incomitant; it is greater on attempted abduction of the affected eye and on distance fixation. Because the greatest motility deficit occurs on an attempt to abduct the affected eye, palpebral fissure widening upon abduction may be seen with maximal abduction effort. The patient may also present with a head turn toward the affected eye, to avoid abduction and thereby minimize diplopia.[15] It is important to differentiate isolated sixth-nerve associated abduction deficit from a gaze palsy or INO, as this would localize the lesion to the nucleus/internuclei of the 6th and 3rd nerves, respectively.[16]

Symptoms

Diplopia is the most common presenting symptom. Patients will have horizontal uncrossed diplopia, which is greater at distance than at near. The diplopia is also worse in the direction of the palsied muscle and gets better in the contralateral gaze. In recent onset palsies, the deviation measures greater when the paretic eye is fixating and smaller when the nonparetic eye is fixatng (primary and secondary deviations, respecting Hering's law).

Other symptoms associated with abducens nerve palsy depend on the underlying etiology. In cases due to raised intracranial pressure, patients may experience associated symptoms of headache, pain around the eyes, nausea, vomiting, or pulse synchronous tinnitus. Low ICP from a CSF leak can also cause abducens palsy and can present with symptoms of headache and thus can present clinically very similarly to raised ICP.[5] If a patient has a lesion causing the abducens nerve palsy that affects other structures in the brain, other neurologic signs may be observed.[17] In the event of subarachnoid hemorrhage, the patients can present with leptomeningeal irritation and with cranial nerve palsies.[18]

If the etiology of the abducens nerve palsy is a brainstem lesion affecting the sixth cranial nerve fasciculus, there may be associated ipsilateral facial weakness, contralateral hemiparesis, or sensory abnormalities (Millard-Gubler syndrome). If the abducens nerve palsy presents together with other ipsilateral cranial nerve palsies, etiology could be a lesion involving the meninges, superior orbital fissure, orbital apex, or cavernous sinus.

Clinical diagnosis

The diagnosis of abducens nerve palsy is usually made on clinical examination. On examination, there is inability to abduct the affected eye. Abducens nerve palsy causes an incomitant esotropia due to the unopposed action of the antagonistic medial rectus muscle. The affected eye turns in toward the nose and is unable to abduct properly. The deviation is usually greater at distance fixation than at near, and also greater on attempted abduction of the affected eye.

Diagnostic procedures

After clinical examination, the most common diagnostic procedure is brain and orbital magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with gadolinium and fat suppression. MRI can be especially useful in localizing abducens nerve lesions and ruling out serious underlying etiologies, especially neoplasm. Additionally, MRI of the brain and orbits can sometimes help distinguish between high and low ICP.

MRI is recommended in all patients under the age of 50, and those who present with nonisolated abducens nerve palsy, have a history of cancer, or have an absence of microvascular risk factors. However, controversy remains regarding the importance of MRI in elderly patients with isolated abducens nerve palsy and vasculopathic risk factors. A prospective study found an etiology other than ischemia in 16.5% of such patients.[19] These included giant cell arteritis, brainstem infarction, petroclival meningioma, and cavernous sinus B cell lymphoma. Due to the possibility of dangerous diseases presenting with an isolated cranial motor neuropathy, the authors recommended MR imaging even if a microvascular cause is suspected.[19] However, a cost-effectiveness study found a relatively low diagnostic yield for MRI imaging in these patients and concluded that it may not be medically necessary to perform an MRI on every patient with an isolated cranial nerve palsy.[20]

Laboratory test

- Complete blood cell (CBC) count

- Glucose levels

- Glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1C)

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- C-reactive protein

- Fluorescent treponemal antibody-absorption test, VDRL or RPR

- Lyme titer

- Glucose tolerance test

- Antinuclear antibody test

- Rheumatoid factor test

- Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE)

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) could be performed for the following:

- Patients younger than 50 years

- Associated pain or other neurologic abnormality

- History of cancer

- Bilateral sixth nerve palsy

- Optic nerve edema

- If no marked improvement is seen after 3 months or other nerves become involved

- Lumbar puncture can be considered if MRI results are negative.

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnosis for abducens nerve palsy includes:

- Vasculopathy: Hypertension, diabetes mellitus, aneurysm

- Congenital: Duane retraction syndrome (Types 1 and 3), essential infantile esotropia

- Infectious/Inflammatory: Sphenoiditis, lateral rectus myositis.

- Autoimmune/Inflammatory: Myasthenia gravis, Miller-Fisher syndrome, thyroid eye disease

- Neoplastic[21]

- Traumatic: Blowout fracture with entrapment of the medial rectus

- Other: Spasm of the near reflex, longstanding esotropia with medial rectus contracture, ocular neuromyotonia

Duane syndrome may be differentiated from an abducens nerve palsy by the presence of narrowing of the lid fissure in adduction, which may be seen in Duane syndrome but not in an abducens nerve palsy.

Thyroid eye disease, although more commonly bilateral, may present with unilateral symptoms including proptosis and symptoms of inflammation upon awakening.[11]

Diplopia in myasthenia gravis fluctuates and is fatigable and with or without generalized fatigability, shortness of breath and hoarseness.[11]

Clinical assessment for orbital, neuromuscular, and brainstem disease is the first step in evaluation for this condition, and after this, an abducens nerve palsy can be diagnosed by exclusion.

Management

General treatment

Treatment of abducens nerve palsy depends on the underlying etiology. In general, underlying or systemic conditions are treated primarily. Most patients with a microvascular abducens nerve palsy are simply observed and usually recover within 3-6 months. Treatment for the diplopia associated with abducens nerve palsy can be managed with prisms, occlusion, botulinum toxin, or surgery.[17] Occlusion using a Bangerter filter or patch can eliminate diplopia and confusion, prevent amblyopia or suppression in children, and decrease the possibility of ipsilateral medial rectus contracture. Base-out Fresnel or ground-in prisms can be used to help the patient maintain binocular single vision in the primary position, but they are not usually useful due to the incomitance of the deviation. Botulinum toxin injections into the medial rectus of the affected eye are sometimes used to prevent secondary contracture of the medial rectus, or during transposition procedures to weaken the nonoperative muscle. In general, surgical intervention is reserved for patients who have had stable orthoptic measurements for at least 6 months.

Surgery

Strabismus surgery can be performed for persistent abducens nerve palsies that demonstrate stable measurements over a 6-month period.[15] A forced duction test is performed in the office or in the operating room in order to assist with surgical planning.

- If there is residual lateral rectus muscle function: often, a resection of the affected lateral rectus and recession of the ipsilateral medial rectus (recess/resect or “R and R” procedure) is performed. Alternatively, a resection of the affected lateral rectus with a recession of the contralateral medial rectus may be performed.

- If there is no lateral rectus muscle function: various forms of transposition surgeries can be considered (eg, full tendon transposition, Jensen, Hummelsheim, Augmented Hummelsheim with resections +/- Foster modifications, Modified Nishida). Superior rectus transposition combined with medial rectus recession has been shown to improve esotropia, head position, and abduction in patients with abducens palsy.[22]

- Botulinum toxin injections to the medial rectus of the affected eye can also be used as a temporizing treatment.

Surgical follow up

Patients may be managed closely postoperatively, and any residual diplopia can be managed with prisms.

Complications

The most likely complication following surgical correction of abducens nerve palsy is the risk of over- or under-correction, which may be managed postoperatively with prisms.

Prognosis

The prognosis for abducens nerve palsy depends on the underlying etiology. One study reported a recovery rate of 49.6% in 419 nonselected sixth nerve palsy cases, and a higher rate of 71% in 419 patients with diabetes mellitus, hypertension, or atherosclerosis.[23]

Additional Resources

- Patient Information Brochure. North American Neuro-Ophthalmology Society (NANOS) https://www.nanosweb.org/cranial_nerve_information_brochure. Accessed March 3, 2025.

References

- ↑ McKay VH, Touil LL, Jenkins D, et al. Managing the child with a diagnosis of Moebius syndrome: more than meets the eye. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2016;101:843-846.

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Teksam O, Keser AG, Konuskan B, Haliloglu G, Oguz KK, Yalnizoglu D. Acute Abducens Nerve Paralysis in the Pediatric Emergency Department: Analysis of 14 Patients. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2016;32(5):307‐311. doi:10.1097/PEC.0000000000000366

- ↑ Emiroglu M, Alkan G, Kartal A, Cimen D. Abducens nerve palsy in a girl with incomplete Kawasaki disease. Rheumatol Int. 2016;36(8):1181‐1183. doi:10.1007/s00296-016-3515-2

- ↑ O'Connor KP, Pelargos PE, Palejwala AH, Shi H, Villeneuve L, Glenn CA. Resection of Pediatric Trigeminal Schwannoma Using Minimally Invasive Approach: Case Report, Literature Review, and Operative Video. World Neurosurg. 2019;127:518‐524. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2019.04.113

- ↑ Jump up to: 5.0 5.1 Hofer JE, Scavone BM. Cranial Nerve VI Palsy After Dural-Arachnoid Puncture. Anesth Analg [Internet]. 2015 Mar [cited 2019 Aug 22];120(3):644–6. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25695579

- ↑ Hanna LS, Girgis NI, El Ella A, Farid Z. Ocular complications in meningitis: fifteen years study. Metab Pediatr Syst Ophthalmol. 1988;11:160-162.

- ↑ Khade N, Carrivick S, Orr C, Prentice D. Recurrent abducens nerve palsy and hypophosphatasia syndrome. BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12(4):e226895. Published 2019 Apr 11. doi:10.1136/bcr-2018-226895

- ↑ Nieto-Calvache AJ, Loaiza-Osorio S, Casallas-Carrillo J, Escobar-Vidarte MF. Abducens Nerve Palsy In Gestational Hypertension: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2017;39(10):890‐893. doi:10.1016/j.jogc.2017.04.031

- ↑ Prasad S, Volpe NJ. Paralytic strabismus: third, fourth, and sixth nerve palsy. Neurol Clin. 2010;28(3):803‐833. doi:10.1016/j.ncl.2010.04.001

- ↑ Anthony CM, Giles GB, Justin GA, Wedel ML, Grant AD. Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease Presenting with Abducens Nerve Palsy. Cureus. 2019;11(9):e5564. Published 2019 Sep 4. doi:10.7759/cureus.5564

- ↑ Jump up to: 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 11.7 Kung NH, Van Stavern GP. Isolated Ocular Motor Nerve Palsies. Semin Neurol. 2015;35(5):539‐548. doi:10.1055/s-0035-1563568

- ↑ Greer CE, Bhatt JM, Oliveira CA, Dinkin MJ. Isolated Cranial Nerve 6 Palsy in 6 Patients With COVID-19 Infection. J Neuroophthalmol. 2020 Dec;40(4):520-522. doi: 10.1097/WNO.0000000000001146. Erratum in: J Neuroophthalmol. 2021 Jun 1;41(2):e276. PMID: 32941331.

- ↑ Nakamizo A, Matsuo S, Amano T. Abducens Nerve Schwannoma: A Case Report and Literature Review. World Neurosurg. 2019;125:49‐54. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2019.01.123

- ↑ Kung NH, Van Stavern GP. Isolated Ocular Motor Nerve Palsies. Semin Neurol. 2015;35(5):539‐548. doi:10.1055/s-0035-1563568

- ↑ Jump up to: 15.0 15.1 Von Noorden GK. Binocular Vision and Ocular Motility: Theory and Management of Strabismus, Third ed.

- ↑ Virgo JD, Plant GT. Internuclear ophthalmoplegia. Pract Neurol. [Internet]. 2017; 17(2):149–53. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27927777

- ↑ Jump up to: 17.0 17.1 Thurtell MJ, Tomsak RJ, Daroff RB. What do I do now? Neuro-ophthalmology. Oxford, New York; 2011.

- ↑ Parr M, Carminucci A, Al-Mufti F, Roychowdhury S, Gupta G. Isolated Abducens Nerve Palsy Associated with Ruptured Posterior Inferior Cerebellar Artery Aneurysm: Rare Neurologic Finding. World Neurosurg. 2019;121:97‐99. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2018.09.096

- ↑ Jump up to: 19.0 19.1 Tamhankar MA. Isolated third, fourth, and sixth cranial nerve palsies from presumed microvascular versus other causes: a prospective study. Ophthalmology. 2013;120:2264–9.

- ↑ Murchison AP, Gilbert ME, Savino PJ. Neuroimaging and acute ocular motor mononeuropathies: a prospective study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011 Mar;129(3):301-5. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2011.25. PMID: 21402985.

- ↑ Khade N, Carrivick S, Orr C, Prentice D. Recurrent abducens nerve palsy and hypophosphatasia syndrome. BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12(4):e226895. Published 2019 Apr 11. doi:10.1136/bcr-2018-226895

- ↑ Mehendale RA, Dagi LR, Wu C, Ledoux D, Johnston S, Hunter DG. Superior Rectus Transposition and Medial Rectus Recession for Duane Syndrome and Sixth Nerve Palsy. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130(2):195–201. doi:10.1001/archophthalmol.2011.384

- ↑ Rush JA, Younge BR. Paralysis of cranial nerves III, IV, and VI. Arch Ophthalmol. 1981;99:76–79