Duane Retraction Syndrome

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Duane Retraction Syndrome is a congenital strabismus syndrome occurring in isolated or syndromic forms. It presents with a variety of clinical features including diplopia, anisometropia, and amblyopia.

Disease Entity

378.71 Duane's syndrome[1]

Disease

Duane retraction syndrome (also known as Stilling-Turk-Duane syndrome) is a congenital, nonprogressive strabismus syndrome originally described by Alexander Duane in 1905.[2][3] Its characteristics include:

- Complete or partial (less common) absence of abduction[2]

- Widening of palpebral aperture with abduction[2]

- Retraction of globe on adduction[2]

- Narrowing of palpebral fissure during adduction (induced ptosis)[2]

- Partial deficiency of adduction[4]

- Oblique movement with attempts at adduction[4]

- Upshoot or downshoot of globe with adduction (Leash Phenomenon)[2]

- Deficiency of convergence[4]

Etiology

Duane retraction syndrome is present in about 1 out of every 1000 persons in the general population, with females making up 60% of affected individuals[3][5][6]. Accounting for up to 4% of all strabismus cases, it is the most common type of congenital aberrant ocular innervation.[5]

There are three major types of Duane retraction syndrome:

- Type 1 (75–80% of patients) presents with an esotropia in primary gaze with a compensatory head turn to the involved side.

- Type 2 (5–10% of patients) presents with an exotropia in primary gaze with a compensatory head turn to the uninvolved side.

- Type 3 (10-20% of patients) can present with either an esotropia or exotropia in primary gaze and involves a compensatory head turn to the involved side. Adduction ability is restricted or absent (vs normal to mildly restricted adduction seen in types 1 and 2).[7]

Most instances of Duane retraction syndrome are isolated with no known association with other diseases. Isolated forms most often occur sporadically and typically are unilateral, with a left eye predominance.[5][6] Ten percent of isolated instances are inherited, and these usually present bilaterally with associated vertical movement abnormalities.[5] The inherited forms can be associated with either dominant or recessive autosomal mutations:

- Type 1: autosomal dominant (locus 8q13)[3]

- Type 2: autosomal dominant (mutation of CHN1 at DURS2 locus 2q31-q32.1)[3][8]and autosomal recessive[8]

About 30% of the time, Duane retraction syndrome is associated with other congenital anomalies (syndromic forms).[5][6] Commonly associated diseases and characteristic features include Okihiro syndrome (radial ray), Wildervanck syndrome (Klippel-Feil anomaly, deafness), Moebius syndrome (congenital paresis of facial and abducens cranial nerves), Holt–Oram syndrome (abnormalities of the upper limbs and heart), Morning Glory syndrome (abnormalities of the optic disc), and Goldenhar syndrome (malformation of the jaw, cheek and ear, usually on one side of the face).[5][6][7] Syndromic forms of Duane restriction syndrome can result from various mutations, depending on the associated syndrome. For example, Okihiro syndrome–related forms are autosomal dominant (SALL4 mutations), Goldenhar syndrome–related instances are mostly sporadic with both autosomal dominant and recessive forms, and Wildervanck syndrome–related instances are irregularly dominant with incomplete penetrance and variable expressivity.[2][7]

General Pathology

Duane retraction syndrome results from absent or dysplastic abducens motor neurons with aberrant innervations of the lateral rectus muscle by the oculomotor nerve.[7]

Pathophysiology

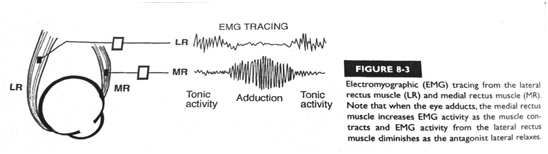

The myogenic theory, suggested by early studies, describes fibrosis or inelasticity of the lateral rectus muscles and abnormally posterior insertion of the medial rectus muscle.[7] The neurogenic theory, which is more commonly accepted, was suggested by postmortem studies conducted by researchers at the John Hopkins University in 1980.[9] This theory proposes that a disturbance in embryologic development between weeks 4–8 results in an absent abducens nerve with anomalous innervations of the lateral rectus muscle by a branch of the oculomotor nerve.[9] Simultaneous activation of the medial and lateral rectus muscles may be the cause of global retraction (Figure 1).[10]

Risk Factors

The only known risk factor for the isolated type of Duane retraction syndrome is an affected parent, which results in a 50% chance of passing the affected gene onto offspring. However, this risk is only associated with 10% of isolated cases, as 90% of these cases have been shown to occur sporadically.[5] An affected parent is also a risk factor for the syndromic forms; however, the chance of passing an affected gene onto offspring varies according to the associated syndrome.

Primary Prevention

No means of primary prevention have been identified.

Diagnosis

Clinical Exam

Frank strabismus in the primary gaze is present in 76% of individuals in Duane retraction syndrome.[3] Other clinical features include compensatory head turn to avoid diplopia (Image 1),[11] limitation of abduction, induced ptosis on adduction (Image 2),[5] poor binocular vision, and anisometropia. Patients generally have good visual acuity, except for those with amblyopia, which is seen in about 10% of individuals but which will respond to standard therapy if detected early.[3]

Laboratory Tests

Molecular genetic testing of CHN1 is available, and is recommended only in familial cases.[7]

Imaging Techniques

Imaging is not recommended for diagnostic purposes. However, brain and orbital MRI can be completed prior to surgical correction for better visualization of orbital anatomy.[7]

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for Duane retraction syndrome includes any condition that demonstrates strabismus or limitations of extraocular movements. This includes, but is not limited to, Okihiro syndrome, Goldenhar syndrome, Wildervanck syndrome, Moebius syndrome, Holt–Oram syndrome, Morning Glory syndrome, abducens nerve palsy, Brown syndrome, Marcus–Gunn jaw winking syndrome, and congenital esotropia.

Management

Evaluation Following Diagnosis

Evaluation should include a family history, with evaluation of family members who may be at risk within the first year of life and consideration for genetic counseling if a familial pattern is identified. Ophthalmic examination should focus on primary gaze, head position, extraocular movements, and aberrant movements, with optional forced duction testing and/or force generation testing. A general physical exam, including hearing evaluation, should also be conducted to assess for the presence of other associated syndromes. Photographic documentation is helpful for future review. [7]

Non-Surgical Management

Spectacles or contact lenses can be prescribed to address refractive error, with prism glasses used to improve compensatory head position.[7] A small study (4 patients) conducted in 2008 found that injections of botulinum toxin may help to decrease the amount of deviation and lessen the upshoot or downshoot of the globe with adduction ("leash phenomenon").[12] Amblyopia can be managed with standard therapy. [7]

Surgical Management

Surgery cannot cure Duane retraction syndrome, but it can correct for the deviation in the primary position, thereby improving a compensatory head position that can occur in some individuals.[7] [13] It can also improve the leash phenomenon.[7]

Indications for Surgery

A patient should be considered for surgical correction if they have at least one of the following characteristics:

- an abnormal head position greater than or equal to 15 degrees[13]

- a significant deviation in the primary position[13]

- severe induced ptosis: a reduction of greater than or equal to 50% of the width of the palpebral fissure on adduction[14]

Pre-Surgical Evaluation

Brain and orbital MRI should be considered before surgery for better visualization of orbital anatomy. Additionally, forced duction testing can be used to confirm tightness of the horizontal rectus muscles.[7]

Contraindications to Surgery

Surgical contraindications include the presence of orthophoria in the primary position, insignificant face turn, and young age.[14]

Principles of Surgical Approach

For types 1 and 3 disease with a head turn, surgery should involve recession of the medial rectus muscle or horizontal transposition of vertical rectus muscles. Types 1 and 3 disease displaying the "leash phenomenon" and/or severe globe retraction should undergo recession of both medial and lateral rectus muscles, with possible Y-splitting of the lateral rectus muscle. For type 2 disease with head turn and fixation with the uninvolved eye, surgery should involve recession of the ipsilateral lateral rectus muscle, whereas fixation with the involved eye should address recession of the contralateral lateral rectus muscle instead. Finally, type 2 disease with "leash phenomenon" should undergo recession of the lateral rectus muscle with possible Y-splitting[7]

Complications of Surgery

Complications can include under-correction of primary position esotropia and the compensatory head turn or over-correction leading to secondary exotropia. New vertical deviations can also occur after vertical rectus transposition procedures.[14]

Surveillance

After diagnosis, ophthalmologic exams are required every 3–6 months to evaluate for amblyopia. Patients aged 7–12 years who are no longer at risk for amblyopia and have good binocular vision can be evaluated annually or biannually.[7]

Additional Resources

For more information on Duane retraction syndrome and for a video of the surgery to correct associated strabismus, visit the Children’s Hospital Boston’s webcast.[15]

References

- ↑ ICD9. 378.71 Duane's syndrome. ICD9. http://icd9.chrisendres.com/index.php?action=child&recordid=3996. [September 24, 2013].

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Kirkham, T.H. Inheritance of Duane's syndrome. Brit. J. Ophthal. 1970; 54 : 323-329.

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 University of Arizona Department of Ophthalmology and Vision Science. Duane Retraction Syndrome 1. Hereditary Ocular Disease. http://disorders.eyes.arizona.edu/disorders/duane-retraction-syndrome-1. [July 14, 2012].

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 4.2 Elliot, A.J. Duane's Retraction Syndrome. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine. 1945; XXXVIII: 463-465.

- ↑ Jump up to: 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 Murillo-Correa CE et al. Clinical features associated with an I126M α2-chimaerin mutation in a family with autosomal dominant Duane retraction syndrome. JAAPOS. 2009;13(3):245-248.

- ↑ Jump up to: 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 National Human Genome Research Institute. Learning About Duane Syndrome. Genome.gov. http://www.genome.gov/11508984. [September 24, 2013].

- ↑ Jump up to: 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 7.11 7.12 7.13 7.14 Andrews CV et al. Duane Syndrome. GeneReviews. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1190/. [July 14, 2012].

- ↑ Jump up to: 8.0 8.1 Miyake N et.al. CHN1 Mutations are not a Common Cause of Sporadic Duane’s Retraction Syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2010;152:215-217.

- ↑ Jump up to: 9.0 9.1 Hotchkiss MG et al. Bilateral Duane's Retraction Syndrome A Clinical-Pathologic Case Report. Arch Ophthalmol.1980;98:870-874.

- ↑ Duane TD. Clinical Ophthalmology. Pediatric Ophthalmic Surgery. Vol. 6. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1994.

- ↑ Gobin MH. Surgical Management of Duane’s Syndrome. Brit. J. Ophthal.1974;58(301):301-306.

- ↑ Talebnejad M et al. Management of Duane’s Syndrome with Botulinum Toxin Injection. Iranian J of Ophthal. 2008;20(3):10-14.

- ↑ Jump up to: 13.0 13.1 13.2 Barbe ME et al. A simplified approach to the treatment of Duane’s syndrome. Br J Ophthalmol. 2004;88:131-138.

- ↑ Jump up to: 14.0 14.1 14.2 Duane TD. Clinical Ophthalmology. Strabismus, Refraction, The Lens. Vol. 1. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1993.

- ↑ Children’s Hospital Boston. Aligning the Eyes. OR Live. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x95WpZtvio0. [September 24, 2013].