Millard-Gubler Syndrome

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Disease Introduction

Millard-Gubler syndrome is clinical constellation of findings, related to a unilateral lesion at the basal portion of the ventrocaudal pons.[1] It is also known as "facial abducens hemiplegia" syndrome or "ventral pontine" syndrome.[2] This article will focus on the neuro-ophthalmic aspects of Millard-Gubler syndrome.

History

Millard-Gubler syndrome was first described by two French physicians in 1858, Auguste Louis Jules Millard and Adolphe-Marie Gubler.[2] It is one of the classical crossed brainstem syndromes first described in the 19th century involving an ipsilateral cranial nerve deficit with contralateral long tract involvement.[1][2][3]

Presentation

Affected Structures

The most common structures involved in Millard-Gubler syndrome include:

- Abducens nerve fibers (cranial nerve VI)

- Facial nerve fibers (cranial nerve VII)

- Pyramidal tract fibers

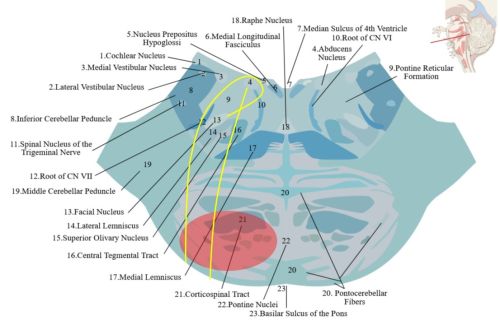

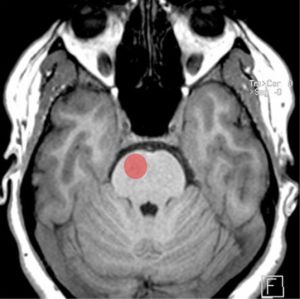

Since Millard-Gubler syndrome affects the ventrocaudal (anteromedial) pons, it does not damage the cranial nerve nuclei but rather the fascicles. The spinothalamic tract and the medial meniscus are not affected as they are dorsal to the lesion; thus somatosensory symptoms would be unexpected.[2] Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the location of Millard-Gubler syndrome.

Figure 1: Damaged area (in red) in Millard-Gubler syndrome affecting the cranial nerve VI (yellow line), cranial nerve VII (yellow line; with a "genu" which wraps around the abducens nucleus), and pyramidal tract fibers (labeled "Corticospinal Tract").[4]Adapted from “Lower Pons horizontal” (https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/d/dc/Lower_pons_horizontal_KB.svg) by Marshall Strother and “Brain stem sagittal section” (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Brain_stem_sagittal_section.svg) by Patrick J. Lynch, medical illustrator. Used under CC BY 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Figure 2: Location of damaged area (red circle) on a normal T1 weighted MRI in Millard-Gubler syndrome.[5] Adapted from case courtesy of Frank Gaillard. https://radiopaedia.org/?lang=us. Radiopaedia.org. From the case https://radiopaedia.org/cases/14278?lang=us. rID: 14278. Used under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/, via Radiopaedia

Vascular Supply to the Pons

There are three vascular territories in the pons:[6]

(1) Anteromedial: supplied by pontine perforating arteries from the basilar artery

(2) Anterolateral: supplied by the anterior inferior cerebellar artery

(3) Lateral: supplied by lateral pontine perforators from the basilar artery, anterior inferior cerebellar artery, or superior cerebellar artery

Miller-Gruber syndrome therefore arises from ischemic related to the basilar artery distribution.

Clinical Manifestations

- Ipsilateral sixth nerve palsy and weakness on abduction of the eye.[2][7][8] Patients can present with esotropia and diplopia worse when the patient looks towards the side of the lesion.[9]

- Ipsilateral facial palsy, leading to flaccid paralysis of the facial muscles.[2][7][8] Patients can also present with loss of the corneal reflex (i.e. reduced reflexive tearing due to impairment of the efferent arm, mediated by the zygomatic branch of cranial nerve VII), but corneal sensation (afferent arm, mediated by the second branch of cranial nerve V) remains.[2]

- Contralateral hemiplegia or hemiparesis of the upper and/or lower extremities.[2][7][8]

- Cerebellar ataxia may be present if damage extends to the middle cerebellar peduncles due to their proximity to cranial nerve VII.[2][7]

Summary Table

| Affected Structures | Clinical Manifestations | Affected Side |

|---|---|---|

| Cranial nerve VI |

|

Ipsilateral |

| Cranial nerve VII |

|

Ipsilateral |

| Pyramidal tract fibers |

|

Contralateral |

Etiology

Several causes of Millard-Gubler syndrome are listed below.

- Hemorrhage[2][8]

- Ischemia[2][8]

- Mass effect (e.g. tumor, prepontine subarachnoid hematoma)[2][7]

- Infectious disease (e.g. tuberculosis, neurocysticercosis, rhombencephalitis)[2][7]

- Demyelinating (e.g. multiple sclerosis)[2]

Mass effect, infectious disease, and demyelinating disease are more likely to be seen in the younger population, whereas cerebrovascular events such as hemorrhage and ischemia to the basilar artery are more common in the elderly population.[2][8]

Diagnostics

Initial Workup

Imaging modalities helpful with the diagnosis of Millard-Gubler syndrome are listed below.

- Imaging

- Non-contrast computed tomography (CT)

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

- Computed tomography angiography (CTA)

If a cerebrovascular cause is suspected, neuroimaging is critical and a non-contrasted CT is usually the initial step due to speed, and an MRI can be used later for a more detailed evaluation. If the cause of Millard-Gubler syndrome is believed to be due to ischemia, CTA is helpful in identifying the area that is occluded.[2][10] Routine bloodwork (e.g. CBC, CMP) along with an ECG and cardiac evaluation can be helpful for evaluating ischemic causes.[11][12] If other causes of Millard-Gubler syndrome are suspected, specific testing should be pursued (e.g. infection, demyelination).

Crossed Brainstem Syndromes

Other crossed brainstem syndromes at the level of the pons to consider include Foville, Raymond, Ramond-Cestan, Gellé, and Brissaud-Sicard, and Gasperini syndrome.[1][2][3] A table summarizing the various syndromes is listed below. A focused history and physical exam along with diagnostic testing is essential in localizing the lesion and distinguishing Millard-Gubler syndrome from other syndromes.[2] Attention should be drawn to the cranial nerves, and assessing other neurological symptoms (e.g. somatosensory deficits, cerebellar symptoms, motor strength).

Summary Table

| Syndrome | Cranial Nerve V | Cranial Nerve VI | Cranial Nerve VII | Cranial Nerve VIII | Pyramidal Tract Fibers | Paramedian Pontine Reticular Formation | Medial Longitudinal Fasciculus | Medial Lemniscus | Spinothalamic Tract | Superior and/or Middle Cerebellar Peduncles |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foville[1][3] | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Raymond[1][2] | X | X | ||||||||

| Raymond-Cestan[1][2] | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Gellé[1] | X | X | X | |||||||

| Brissaud-Sicard[1][2] | X | X | ||||||||

| Gaspirini[2][13] | X | X | X | X | X |

Management

General Management

For suspected acute ischemic stroke, the patient should be hospitalized for emergent neurological workup and management. Tissue plasminogen activator can be used if administered within the 3-4.5 hour window of symptom onset. Patients are frequently given antiplatelet therapy along with a lipid lowering agent (e.g. statin) in such situations.[11]

Secondary prevention in cerebrovascular disease is vital, including blood pressure control, diabetes management, hyperlipidemia, and smoking cessation. Collaboration with other specialties such as neurology, internal medicine, physical medicine and rehabilitation, and other medical subspecialties is common.[11]

Management of Ophthalmic Symptoms

Diplopia

For patients with persistent diplopia due to cranial nerve VI involvement, several treatment options are possible:

- Base-out prism to treat esotropia[9]

- Botulinum toxin to the medial rectus of the affected eye[9]

- Strabismus surgery[9]

Prisms can be used alone or after strabismus surgery to correct residual deviation. Botulinum toxin offers temporary reduction in esodeviation and may reduce secondary constriction. Strabismus surgery is typically reserved for patients who have had stable measurements for at least six months.[9]

Loss of Corneal Reflex

Treatment options are also available for patients who have a loss of the corneal reflex due to cranial nerve VII involvement. These are listed below.

- Ocular surface lubrication (e.g. artificial tears, ophthalmic ointments)[14][15]

- Botulinum toxin to the levator palpebrae superioris muscle[14][15]

- Surgical therapy (e.g. tarsorrhaphy, upper eyelid weight)[14][15]

Ocular surface lubrication is used in the acute setting while botulinum toxin and surgical therapy are typically reserved for patients where recovery is deemed unlikely or if conservative management fails.[14][15]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 Silverman IE, Liu GT, Volpe NJ, Galetta SL. The Crossed Paralyses. Arch Neurol. 1995;52(6):635. doi:10.1001/archneur.1995.00540300117021

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 2.18 2.19 2.20 2.21 Sakuru R, Elnahry AG, Bollu PC. Millard-Gubler Syndrome. In:StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532907/

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Beucler N, Boissonneau S, Ruf A, Fuentes S, Carron R, Dufour H. Crossed brainstem syndrome revealing bleeding brainstem cavernous malformation: an illustrative case. BMC Neurol. 2021;21(1):204. doi:10.1186/s12883-021-02223-7

- ↑ Adapted from “Lower Pons horizontal” (https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/d/dc/Lower_pons_horizontal_KB.svg) by Marshall Strother and “Brain stem sagittal section” (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Brain_stem_sagittal_section.svg) by Patrick J. Lynch, medical illustrator. Used under CC BY 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- ↑ Adapted from case courtesy of Frank Gaillard. https://radiopaedia.org/?lang=us. Radiopaedia.org. From the case https://radiopaedia.org/cases/14278?lang=us. rID: 14278. Used under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/, via Radiopaedia

- ↑ Biniyam A. Ayele, Yonas Tadesse, Betesaida Guta, Guta Zenebe; Millard-Gubler Syndrome Associated with Cerebellar Ataxia in a Patient with Isolated Paramedian Pontine Infarction – A Rarely Observed Combination with a Benign Prognosis: A Case Report. Case Rep Neurol3 May 2021; 13 (1): 239–245.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 Ayele BA, Tadesse Y, Guta B, Zenebe G. Millard-Gubler Syndrome Associated with Cerebellar Ataxia in a Patient with Isolated Paramedian Pontine Infarction – A Rarely Observed Combination with a Benign Prognosis: A Case Report. Case Rep Neurol. 2021;13(1):239-245. doi:10.1159/000515330

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 Patel S, Bhakta A, Wortsman J, Aryal BB, Shrestha DB, Joshi T. Pontine Infarct Resulting in Millard-Gubler Syndrome: A Case Report. Cureus. 2023;15(2):e34869. doi:10.7759/cureus.34869

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 Graham C, Mohseni M. Abducens Nerve Palsy. In:StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482177/

- ↑ Shafaat O, Sotoudeh H. Stroke Imaging. In:StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK546635/

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Tadi P, Lui F. Acute Stroke. In:StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK535369/

- ↑ Yasuda Y, Matsuda I, Sakagami T, Kobayashi H, Kameyama M. Pontine Infarction with Pure Millard-Gubler Syndrome: Precise Localization with Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Eur Neurol. 1993;33(4):333-334. doi:10.1159/000116965

- ↑ Krasnianski M, Müller T, Zierz S, Winterholler M. Gasperini syndrome as clinical manifestation of pontine demyelination. Eur J Med Res. 2009;14(9):413. doi:10.1186/2047-783X-14-9-413

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Rahman I, Sadiq SA. Ophthalmic Management of Facial Nerve Palsy: A Review. Surv Ophthalmol. 2007;52(2):121-144. doi:10.1016/j.survophthal.2006.12.009

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Lee S, Lew H. Ophthalmologic Clinical Features of Facial Nerve Palsy Patients. Korean Journal of Ophthalmology. 2019;33(1):1. doi:10.3341/kjo.2018.0010