Stickler Syndrome

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Stickler syndrome was originally described by pediatrician Gunnar B. Stickler in 1965, as hereditary progressive arthro-ophthalmopathy.[1]

Stickler syndrome is a systemic connective tissue disorder characterized by defective collagen production.[2] The condition is commonly associated with ophthalmologic manifestations including cataract, glaucoma, vitreous abnormalities, congenital megalophthalmos causing myopia, radial perivascular retinal lattice degeneration, and retinal detachment, in addition to systemic findings which may include orofacial, auditory and musculoskeletal abnormalities. Upto sixty percent of Stickler patients can develop rhegmatogenous retinal detachment and severe visual morbidity as a result.

Disease Entity

Stickler syndrome ICD-9 759.89

Disease

Stickler syndrome a genetically inherited abnormality in collagen production that produces a number of pathologic maxillofacial, ocular, auditory and joint manifestations.

Etiology

Types 1-4 Stickler syndrome are classically inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion[3], though a significant number of cases may be sporadic.[2]. Type 5 has only ocular involvement (COL2A1). The majority of cases that present to an ophthalmology outpatient department will be either Type 1 or Type 2 Stickler syndrome.[4] There are many cases with recessive inheritance as well. [5]

Risk Factors

The only known risk factor for Stickler syndrome is a family history of the condition. The child of an affected parent with dominant inheritance has at least a 50% chance of inheriting the pathologic variant. If both parents are heterozygous for an autosomal recessive Stickler syndrome, there is a 25% chance of having the disease, a 50% chance of being heterozygous and an asymptomatic carrier, and a 25% chance of being unaffected with no pathologic variant. [5]

Pathophysiology

Stickler syndrome is believed to be a direct result of abnormalities in the production of collagen types II, IX and XI, all of which are recognized as components of the human vitreous.[2] Normal collagen fibrils are composed of three identical (homotrimer) or differing (heterotrimer) polypeptide chains; genetic mutations affecting the ability of constituent polypeptide chains to successfully form stable trimers therefore prevent the production of mature collagen and subsequently produce the clinical manifestations of Stickler syndrome. The condition has been divided into subgroups based on ocular and systemic clinical findings, with each subgroup also corresponding to a specific genetic defect.[2]

| Type | Clinical features | Gene |

|---|---|---|

| Type 1 (STL1) | Membranous vitreous, congenital megalophthalmos, arthropathy, deafness, Pierre Robin sequence | COL2A1 |

| Type 2 (STL2) | Fibrillar or Beaded vitreous, otherwise similar to type 1 | COL11A1 |

| Type 3 (STL3) | No ocular involvement, otherwise similar to type 1 | COL11A2 |

| Type 4 (STL4) | Membranous vitreous, congenital megalophthalmos; no systemic findings | COL9A1, COL9A2 |

Primary prevention

Because Stickler syndrome is related to a genetic abnormality, there is no known primary prevention. Genetic counseling may be beneficial for affected patients of childbearing age. The most severe visual morbidity in these patients is due to retinal detachment seen in 60% of patients.

Recent studies have suggested that prophylactic peripheral retinal cryotherapy or laser may be effective in reducing the risk of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment, the most common cause of acute visual loss in affected patients (see Surgery section below).

Diagnosis

History

Stickler syndrome classically presents in the pediatric population due to the characteristic facies associated with Pierre-Robin sequence. Ophthalmic manifestations, if not detected early, may not present until a retinal detachment develops; classically, this occurs in young adulthood, but may occur at any age. Pertinent history may be elicited by inquiring specifically about associated symptoms of hearing loss and joint pain.

Signs

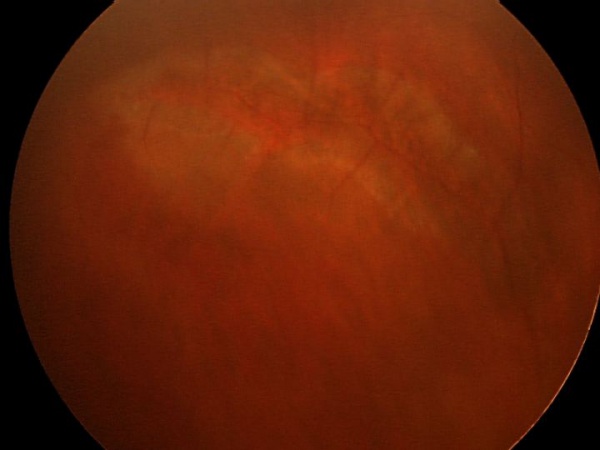

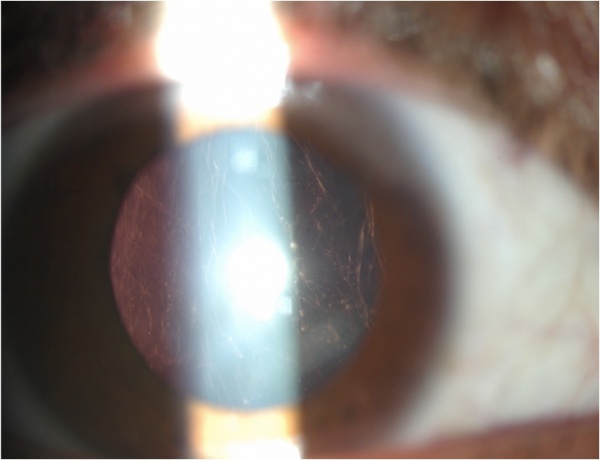

The most common ocular findings in Stickler syndrome are vitreous syneresis in a membranous or beaded configuration and radial perivascular retinal lattice degeneration, both of which are present in up to 100% of affected patients[6]. These vitreoretinal abnormalities may lead to a giant retinal tear and rhegmatogenous retinal detachment in up to 50% of patients. Other findings include axial myopia (present in 80%) resulting from megalophthalmos, open-angle glaucoma resulting from anterior segment dysgenesis,[7][8] and cataract. The cataract is typically a congenital quadrantic lamellar opacity, which may not involve the visual axis.

Systemic findings may include micrognathia and macroglossia resulting in cleft palate (Pierre-Robin sequence: an unusually small mandible (micrognathia), posterior displacement or retraction of the tongue (glossoptosis), upper airway obstruction, and cleft palate), evidence of osteoarthritis on hip, spine and knee radiography, and hearing loss, which may be conductive, sensorineural, or both. The presence of a cleft palate or a typical Pierre-Robin sequence facies may be readily apparent and provide helpful diagnostic information.

Symptoms

Ocular symptoms may include visual field loss related to rhegmatogenous retinal detachment, as well as decreased acuity secondary to myopia or cataract. Systemic symptoms may include hearing loss and joint pain.

Clinical diagnosis

The diagnosis of Stickler syndrome has historically been based on the presence of characteristic clinical features; in Types 1-3, the systemic findings may prompt ophthalmic referral prior to development of any visual complaints. Type 4, the ocular-only variant, may remain asymptomatic prior to routine eye examination or development of retinal detachment; the ophthalmologist therefore plays a key diagnostic role in these cases[2]. Reflecting its large collagen content, the vitreous is the primary ocular site affected in Stickler syndrome. Classically, the Stickler vitreous is described as “optically empty”[3], though differing phenotypes have been described based on slit lamp findings: The so-called membranous vitreous appears as a collection of gel in the immediate retrolental space, posteriorly bounded by a membranous condensation. The beaded vitreous contains diffuse, sparse lamellae with a beaded appearance. A third variant has been described as a generally hypoplastic vitreous with the “optically empty” appearance but lacking the membranous or beaded features. As noted above, the membranous and beaded phenotypes are associated with the COL2A1 and COL11A1 genes, respectively; this relationship has proven useful in performing targeted molecular genetic analysis.

Due to the difficulty in slit-lamp examination of infants and young children, the earliest ophthalmic findings noted may be the characteristic radial perivascular retinal degeneration visible on indirect ophthalmoscopy. This finding is not present at birth, but may be seen within the first 4 years of life, and typically manifests as patches of retinal pigment epithelium atrophy around the major vessels which subsequently become darkly hyperpigmented. In ocular-only variants, this may be the only obvious clue to early pediatric diagnosis.[6] Retinal tears, when present, typically occur at the edge of an atrophied area.

Diagnostic procedures

Diagnosis of Stickler syndrome is clinical. Targeted molecular genetic analysis based on the vitreous phenotype has been successful, though the benefit of genetic screening is unclear at this time. Detection of the typical ophthalmic findings generally warrants evaluation for associated systemic abnormalities; this would include audiometric and radiographic evaluation.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis includes other type II/XI collagenopathies:

- Multiple epiphyseal dysplasia

- Kniest dysplasia (Metatropic dwarfism, type II)

Management

General treatment

Treatment of Stickler syndrome involves both prophylaxis and treatment of its complications, most commonly retinal detachment.

Medical therapy

With the possible exception of topical ocular antihypertensives for associated glaucoma, there is no effective medical treatment for prophylaxis or amelioration of the ocular signs and symptoms of Stickler syndrome. Medical treatment by the pediatrician or primary care physician may be beneficial for the associated precocious osteoarthritis.

Surgery and Prophylaxis

Retinal detachment is a common cause of visual loss in patients with Stickler syndrome, occurring in up to 65% of affected patients. Stickler syndrome is the most common inherited cause of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment.[9] Detachment causing visual loss most typically occurs in young adulthood, but may occur within the first five years of life. Patients are particularly at risk of developing a giant retinal tear (GRT), which typically occurs during posterior vitreous detachment. Associated retinal detachments are notoriously difficult to manage and patients are prone to development of proliferative vitreoretinopathy (PVR).[10] Treatment with primary vitrectomy is generally more successful than scleral buckling procedures and has been suggested to the procedure of choice in Stickler syndrome-related retinal detachment. However, a recent study comparing pars plana vitrectomy (PPV), scleral buckle (SB), and combination pars plana vitrectomy and scleral buckle found initial scleral buckle had better visual acuity and anatomic outcomes in treating retinal detachments in syndromes with optically empty vitreous.[11]

Prophylactic treatment of peripheral retina using 360° cryotherapy or circumferential laser is effective in reducing rates of retinal detachment (RD). Both treatment modalities have been retrospectively compared to observation and both are apparently effective in significantly decreasing risk of RD. However, there has not been a study directly comparing the two modalities, and meta-analyses have not shown one to be superior to the other.[12][13] The Cambridge Prophylactic Cryotherapy Protocol study in patients with type 1 Stickler syndrome found that untreated control patients had a 7.4-fold increased risk of RD compared to patients who had bilateral 360° transconjunctival prophylactic cryotherapy. The rate of RD was 53.6% in the bilateral control group and 8.3% in the bilateral prophylaxis group.[14] A study of 360° extended vitreous base laser prophylaxis in Stickler syndrome found a significant reduction in the rate of RD with laser treatment (3% incidence of RD) as compared to no treatment (73% incidence of RD). Additionally, this study found that eyes that received extended vitreous base laser had approximately 8 lines better vision on average compared to untreated eyes. In this study, laser was applied from the ora serrata to the equator for 360° with laser burn spacing between one half to 1 spot size.[15] Morris et al. reported successful prophylaxis of retinal detachment in 5 treated eyes of patients with Stickler Syndrome Type 2 using encircling grid laser from 2mm onto the pars plana to the ora and 4mm posteriorly, followed by extension of the laser posteriorly to and between the vortex vein ampullae 3 months later, to protect against more posterior retinal defects.[16] It has been recommended that the option for prophylactic treatment be discussed with patients and their families in early life.[10]

Patients with associated open-angle glaucoma may require surgical intervention. The availability of published data to guide management in such cases is limited; however, glaucoma in Stickler syndrome is presumed to be related to anterior segment dysgenesis and therefore angle surgery (goniotomy or trabeculotomy) may be beneficial. Filtering procedures remain viable options for refractory cases.

As noted above, the typical cataract found in Stickler syndrome is of a congenital quadratic lamellar type.[2] Such cataracts may or may not negatively impact vision; if decreased vision is present, removal may be performed with standard lensectomy or phacoemulsification. Patients are at an increased risk of both vitreous loss and post-operative retinal detachment; retinal breaks should be addressed prior to cataract surgery.[3]

Follow up

Untreated patients and patients who have undergone prophylactic cryotherapy or laser remain at increased lifetime risk of retinal detachment. Patients who have undergone operative repair of retinal detachment similarly remain at risk for re-detachment and all patients should be monitored regularly on a long-term basis.

Patients undergoing glaucoma angle or filtering procedures and patients undergoing cataract extraction require routine follow up.

Prognosis

There is currently no available data on long-term visual prognosis of Stickler syndrome; however, prophylactic treatment to prevent retinal detachment is expected to improve long term visual prognosis. Ocular and systemic abnormalities are progressive and the rate of significant disability from blindness, hearing loss and crippling arthritis would be expected to increase with increasing age.

Additional Resources

- Retinal Detachment

- Scleral buckling for rhegmatogenous retinal detachment

- Stickler Syndrome. American Academy of Ophthalmology. EyeSmart/Eye health. https://www.aao.org/eye-health/diseases/stickler-syndrome-list. Accessed March 25, 2019.

References

- ↑ STICKLER G. HEREDITARY PROGRESSIVE ARTHRO-OPHTHALMOPATHY. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 1965-06;40:433-55.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Snead M. Stickler syndrome, ocular-only variants and a key diagnostic role for the ophthalmologist. Eye (London). 2011-11;25:1389-400.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, Section 6. Basic and Clinical Science Course, AAO, 2011-2012.

- ↑ Gurnani B, Kaur K. A rare case of stickler marshall syndrome. TNOA J Ophthalmic Sci Res 2020;58:203-5

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Mortier G. Stickler Syndrome. 2000 Jun 9 [updated 2023 Sep 7]. In: Adam MP, Feldman J, Mirzaa GM, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJH, Gripp KW, Amemiya A, editors. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993–2023. PMID: 20301479.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 E.S. Parma, J. Korkko, W.S. Hagler, L. Ala-Kokko. Radial perivascular retinal degeneration: a key to the clinical diagnosis of an ocular variant of Stickler syndrome with minimal or no systemic manifestations. Am J Ophthalmol, 134 (2002), pp. 728–734

- ↑ Ziakas NG, Ramsay AS, Lynch SA, Clarke MP. Stickler's syndrome associated with congenital glaucoma. Ophthalmic Genet. 1998 Mar;19(1):55-8. doi: 10.1076/opge.19.1.55.2177. PMID: 9587930.

- ↑ Shenoy BH, Mandal AK. Stickler syndrome associated with congenital glaucoma. Lancet. 2013 Feb 2;381(9864):422. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61813-3. PMID: 23374481.

- ↑ Ang A. Retinal detachment and prophylaxis in type 1 Stickler syndrome. Ophthalmology (Rochester, Minn.). 2008-01;115:164-8.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Retina and Vitreous, Section 12. Basic and Clinical Science Course, AAO, 2011-2012.

- ↑ Taylor K, Su M, Richards Z, Mamawalla M, Rao P, Chang E. Outcomes in Retinal Detachment Repair and Laser Prophylaxis for Syndromes with Optically Empty Vitreous. Ophthalmol Retina. 2023 Jun 23:S2468-6530(23)00280-4. doi: 10.1016/j.oret.2023.06.012. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 37356493.

- ↑ Carroll C. The clinical effectiveness and safety of prophylactic retinal interventions to reduce the risk of retinal detachment and subsequent vision loss in adults and children with Stickler syndrome: a systematic review. Health technology assessment (Winchester, England). 2011-04;15:iii-xiv, 1-62.

- ↑ K.B. Boysen, M. La Cour, L. Kessel. Ocular complications and prophylactic strategies in Stickler syndrome: a systematic literature review. Ophthamic Genet, 41 (2020), pp. 223-234, 10.1080/13816810.2020.1747092

- ↑ Fincham GS, Pasea L, Carroll C, McNinch AM, Poulson AV, Richards AJ, Scott JD, Snead MP. Prevention of retinal detachment in Stickler syndrome: the Cambridge prophylactic cryotherapy protocol. Ophthalmology. 2014 Aug;121(8):1588-97. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.02.022. Epub 2014 May 1. PMID: 24793526.

- ↑ Khanna S, Rodriguez SH, Blair MA, Wroblewski K, Shapiro MJ, Blair MP. Laser Prophylaxis in Patients with Stickler Syndrome. Ophthalmol Retina. 2022 Apr;6(4):263-267. doi: 10.1016/j.oret.2021.11.001. Epub 2021 Nov 11. PMID: 34774838.

- ↑ Morris RE, Parma ES, Robin NH, Sapp MR, Oltmanns MH, West MR, Fletcher DC, Schuchard RA, Kuhn F. Stickler Syndrome (SS): Laser Prophylaxis for Retinal Detachment (Modified Ora Secunda Cerclage, OSC/SS). Clin Ophthalmol. 2021 Jan 6;15:19-29. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S284441. PMID: 33447008; PMCID: PMC7802593.