Posterior Vitreous Detachment

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Disease

Posterior Vitreous Detachment (PVD) is a separation between the posterior vitreous cortex and the neurosensory retina, with the vitreous collapsing anteriorly towards the vitreous base. Changes occur with advancing age in the enzymatic activities in the vitreous and vitreoretinal interface that promote vitreous separation from the inner retinal surface. [1]

Pathophysiology

The vitreous is strongly attached to the retina at the vitreous base, a ring shaped area encircling the ora serrata (2mm anterior and 4mm posterior to it). The vitreous is also adherent to the optic disc margin, macula, main retinal vessels and some retinal lesions such as lattice degeneration.

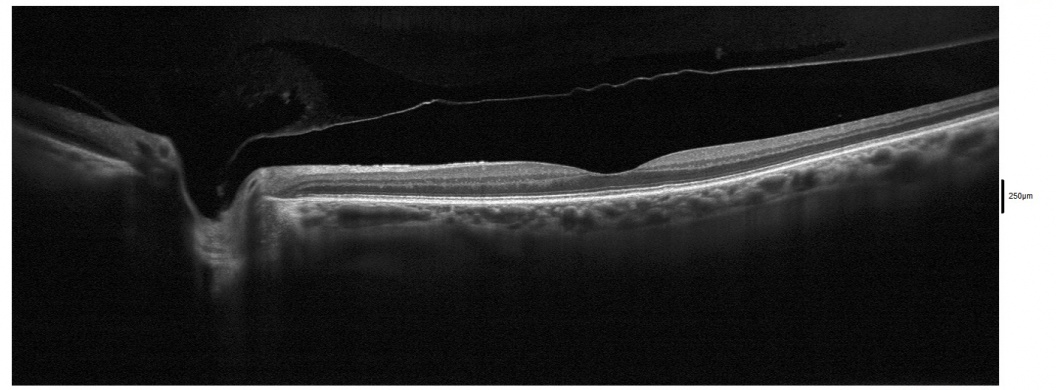

The initial event is liquefaction and syneresis of the central vitreous. A rupture develops in the posterior hyaloid (or vitreous cortex) through which liquefied vitreous flows into the retrovitreous space, separating the posterior hyaloid from the retina. It typically starts as a partial PVD in the perifoveal region and is usually asymptomatic until it progresses to the optic disc, when separation of the peripapillary glial tissue from the optic nerve head occurs, usually with formation of a Weiss ring and accompanying symptoms.

Vitreous traction at sites of firm adhesion may result in a retinal tear with or without subsequent rhegmatogenous retinal detachment.

Epidemiology

Prevalence of PVD increases with age and with axial length of the eye. PVD affects most eyes by the eighth decade of life. Age at onset is generally in sixth to seventh decade and men and women appear to be equally affected.

Risk Factors

PVD occurs earlier in myopic eyes, in eyes with inflammation, following blunt trauma, or cataract surgery (especially when there is surgical vitreous loss).

Diagnosis

Signs and symptoms

Many patients do not present with acute symptoms when PVD occurs.

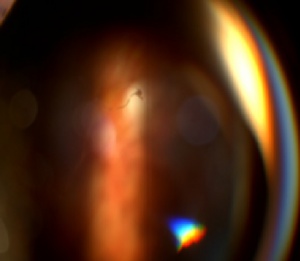

Presenting symptoms include entoptic phenomena such as floaters, change in pattern of floaters and photopsias. Floaters are the most common complaint and result from vitreous opacities such as blood, glial cells or aggregated collagen fibers torn from the margin of the optic disc. They move with vitreous displacement during eye movement and scatter incident light, which casts a shadow on the retina that is perceived as a grey structure resembling "hairs", "flies" or "spiderwebs". Floaters may continue indefinitely although they usually gradually diminish over time. Photopsias are caused by physical stimulation of the retina from vitreoretinal traction. They reportedly occur in 50% of symptomatic PVD and are usually vertical and temporally located. Some patients may describe it as a "haze" that comes and goes.

An alteration in peripheral visual field may indicate a retinal detachment.

Physical Examination

Indirect ophthalmoscopy with scleral indentation and slit lamp exam with a three-mirror lens are the preferred techniques to confirm PVD and to exclude retinal tears or retinal detachment.

The presence of vitreous hemorrhage or pigment may indicate a retinal tear (15% of patients with symptomatic PVD have a retinal tear, as opposed to 50%-70% of patients with PVD+vitreous haemorrhage). If significant hemorrhage interferes with complete examination, bed rest with head at 45º for hours or days with optional bilateral ocular patching may help restore transparency in order to rule out retinal tears. If the source of bleeding cannot be found, the patient should be re-examined regularly and pars plana vitrectomy may be considered to identify a source.

Echography may be useful in detecting retinal tears with flap or retinal detachment, especially if haemorrhage or other opacification of media limits visualization. Ultrasonography cannot rule out retinal tears.

Patients are given strict return precautions and often re-examined within 2-6 weeks after presentation to assess for retinal breaks or detachment with a PVD in evolution.

Differential diagnosis

- Retinal detachment

- Asteroid hyalosis/Synchysis scintillans

- Vitreous syneresis

- Vitreous inflammation (infectious and non infectious)

- Vitreous hemorrhage

- Vitreous amyloidosis

- Ocular large cell lymphoma

Management

General treatment

Observation with strict retinal detachment precautions and follow up exam to rule out retinal breaks. Vitrectomy can be considered for non-clearing vitreous hemorrhage, or vision threatening pathology.

Medical therapy

There are no medical therapies recommended for a PVD.

Medical follow up

After the diagnosis of an acute PVD, a follow up dilated fundus examination should be performed approximately 1 month afterwards. It is possible for a new retinal tear or retinal detachment to occur during this dynamic period. Strict recommendation of urgent follow-up is given to the patient for onset of recurrent photopsias with an increase in floaters.

PVD usually develops in the fellow eye between 6 months to 2 years. [2]

Surgery

There are no surgical indications for routine PVDs. If a partial PVD is present that is causing vision threatening vitreomacular traction syndrome, pars plana vitrectomy with membrane peeling may be indicated. Resolution occurs in half of patients with VMT; others may progress to a lamellar hole or a macular hole. Serial OCT scans can be used to assess for progression every 1-3 months.

Complications

PVDs are occasionally associated with vitreous hemorrhage, retinal tear and retinal detachment. These should be ruled out during dilated fundus examination of patients with a PVD. In a large study of 8305 patients with acute PVD symptoms, Siedel et al [3]reported retinal tears (RTs) in 5.4% and and RRD in 4.0% of patients with symptomatic PVD. A higher risk of RT or RRD was noted in patients with blurred vision, male gender, age < 60 years, previous keratorefractive surgery or cataract surgery, with presence of vitreous pigment or hemorrhage, lattice degeneration. Late RTs or RRDs occurred in 12.4% of patients with all 3 risk factors - vitreous hemorrhage, lattice degeneration, or a history of RT or RRD in the fellow eye.

Follow-up examination every 3-6 weeks for 3 months should be considered for acute symptomatic PVDs. Long term complications may include vitreo-macular traction, lamellar macular holes, full-thickness macular holes and epiretinal membranes.

Prognosis

The visual prognosis is generally good with PVD.

Additional Resources

- Boyd K, Gregori NZ. What Are Floaters and Flashes? American Academy of Ophthalmology. EyeSmart/Eye health. https://www.aao.org/eye-health/diseases/what-are-floaters-flashes. Accessed March 28, 2023.

- Porter D, Vemulakonda GA. What Is a Posterior Vitreous Detachment? American Academy of Ophthalmology. EyeSmart/Eye health. https://www.aao.org/eye-health/diseases/what-is-posterior-vitreous-detachment. Accessed March 28, 2023.

- ↑ Hikichi T. Time course of posterior vitreous detachment in the second eye. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2007 May;18(3):224-7.

- ↑ Hikichi T. Time course of posterior vitreous detachment in the second eye. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2007 May;18(3):224-7.

- ↑ Seider MI, Conell C, Melles RB. Complications of Acute Posterior Vitreous Detachment. Ophthalmology. 2022 Jan;129(1):67-72.