Wagner Syndrome

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Disease

Wagner syndrome is an autosomal dominant vitreoretinopathy that results in a variety of ocular findings. The characteristic feature of the syndrome is an “optically empty” vitreous. Myopia, vitreous veils, presenile cataract, and night blindness are also commonly associated findings.[1]

Etiology

Wagner syndrome is caused by a mutation in the VCAN gene encoding the proteoglycan versican.[1]

Risk Factors

There are no known risk factors other than genetic predisposition. Wagner syndrome is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern though de novo mutations have been reported. [1]

Pathophysiology

Wagner syndrome is very rare. The estimated prevalence is less than 1:1,000,000. There are an estimated 100 cases both familial and simplex (single occurrence in a family) reported in the literature.[2] It does not appear to have a specific ethnicity that it favors as it has been reported in families of European, Asian, African-American, and Caucasian-American ethnicity.[1][3][4][5][6][7]

Molecular genetics

As mentioned, Wagner syndrome is caused by a mutation in the VCAN gene. VCAN is located at chromosome 5q13-15 and encodes an extracellular matrix proteoglycan named versican.[1][8] Mutations to VCAN have complete penetrance, and all patients with a VCAN mutation develop Wagner syndrome in varying degrees. All the VCAN mutations found that result in Wagner syndrome have been mutations at the splice acceptor or splice donor site of introns 7 and 8.[1][3][9][10]

Keller et al. showed that the alternative splicing events resulting from VCAN mutations can lead to changes in glycosaminoglycan attachment sites and other extracellular matrix-binding regions of versican.[7] It is thought that under normal circumstances these glycosaminoglycan regions of versican may prevent collagen fibrils from adhering, giving the vitreous its gel-like qualities.[1][5] Mutations at the splice donor or acceptor site result in aberrant forms of versican and may result in a greatly reduced amount of glycosaminoglycans in proteins, leading to premature liquefaction of the vitreous.[1]

Primary prevention

Since Wagner syndrome is a genetic disorder, there is nothing currently that can prevent its manifestations. Though prenatal genetic counseling could be beneficial for family planning.

Diagnosis

In general, patients presenting for evaluation for Wagner syndrome have a confirmed family history of the syndrome. In a patient with a positive family history and the corresponding clinical findings covered below, one can establish the diagnosis of Wagner syndrome. If a patient does not have a family history of the syndrome but is suspected to have Wagner syndrome due to history and exam findings, genetic testing for mutations of the VCAN gene can aid in diagnosis.[1]

History

Patients will often present for evaluation of Wagner syndrome due to a family history of the syndrome. Otherwise, patients may present with vision concerns. The first signs of vitreous degeneration seen in Wagner syndrome usually develop during early adolescence but may be seen as early as age two years.[3]

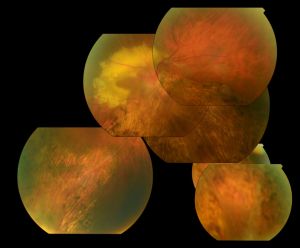

Physical examination

Optically empty vitreous on slit-lamp exam with avascular vitreous strands and veils is the defining characteristic of Wagner syndrome. Other associated findings include mild to severe myopia, presenile cataract of varying type, and varying degrees of night blindness secondary to associated progressive chorioretinal atrophy. Retinal traction and detachment can occur in advanced disease.[1] Uveitis has also been described in some cases.[1][4][5][11]

Nonspecific changes of the retinal pigment epithelium and overlying retina may also occur. These changes include but are not limited to pigment condensation, vascular sheathing, pigmented lattice degeneration, and peripheral chorioretinal atrophy.[1]

Some other occasional ocular features include spherophakia, ectopic fovea, synchysis scintillans, optic atrophy, and exudative vitreoretinopathy. No systemic abnormalities are associated with Wagner syndrome.[1][3][4][5][6]

Symptoms

Patients can experience poor vision secondary to myopia, cataract, retinal traction, or epiretinal membranes. Loss of vision may occur secondary to retinal detachment. Night blindness is also common, but it is not as severe as that seen with retinitis pigmentosa.[1]

Diagnostic procedures

Electroretinogram (ERG)

Full-field ERG is attenuated in patients with Wagner syndrome. Both a-wave and b-wave amplitude are reduced. The rod and cone systems are affected as well, but abnormalities vary from patient to patient.[1][3][4][5][6]

Visual Field

Visual field testing may be abnormal and may show constricted visual fields.[11]

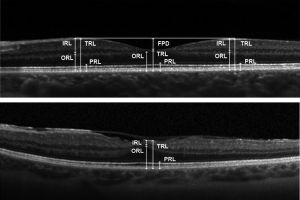

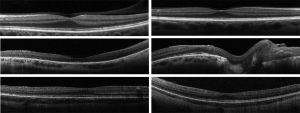

Optical coherence tomography (OCT)

OCT may show outer retinal disruption.[11] Nearly all layers of the retina ca have significantly reduced thickness consistent with chorioretinal atrophy.[13] OCT may also show multilayered membranes of high reflectivity at the vitreoretinal surface. These membranes are detached from the vitreofoveal interface but tend to stay attached to the perifoveal region, creating a bridge over the fovea. This differs from the typical posterior vitreous detachment related to age, as that tends to start in the perifovea region and stay attached to the fovea itself.[13] These attachments can generate signs of a mid-peripheral tractional ridge on OCT, which with underlying myopia can be suspicious for Wagner syndrome[14].

OCT angiography (OCTA) may show perivascular loss of the superficial retinal capillary plexus in cases of Wagner syndrome[14].

Laboratory testing

Single-gene testing can be used to determine the exact mutation in the VCAN gene. Sequence analysis of the splice acceptor and splice donor site of introns 7 and 8 is the best first step, as all pathogenic mutations associated with Wagner disease have been found at this site. Sequence analysis of the entire gene should be done if targeted testing is not available.[1]

Multigene panels that include VCAN and genes related to other syndromes on the differential diagnosis for Wagner syndrome are available and may be considered.[1]

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnsosis for Wagner’s Syndrome includes:[1][3][5][6]

- Erosive Vitreoretinopathy (ERVR)

- Stickler Syndrome

- Jansen Syndrome

- Autosomal Dominant Exudative Vitreoretinopathy (FEVR)

- Snowflake Vitreoretinal Degeneration (SVD)

- Autosomal Dominant Vitreoretinochoroidopathy (ADVIRC)

- Autosomal Dominant Neovascular Inflammatory Vitreoretinopathy (ADNIV)

- Goldmann-Favre Syndrome

- Enhanced S-Cone Syndrome

- Knobloch Syndrome

Management

A complete ophthalmological exam is necessary in patients diagnosed with Wagner syndrome to assess the extent of disease. This should include best-corrected visual acuity, slit-lamp examination, measurement of intraocular pressure, and indirect ophthalmoscopy. Ancillary testing should include visual field examination, fundus photography, optical coherence tomography, electroretinogram and orthoptic assessment. Patients should also be referred to a clinical geneticist and/or a genetic counselor.[1]

Children should also be monitored for amblyopia due to the high incidence of myopia in Wagner syndrome.

In Wagner syndrome, the prevalence of retinal detachment (RD) is much higher than the general population but also significantly variable from family to family.[3][5][6] Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment (RRD) is the most common type of RD and its prevalence ranges from 6.3 to 17.9 per 100,000 subjects per year.[16] In a follow-up of the original Swiss family, peripheral tractional RD was actually more commonly seen than RRD. RRD was only reported in four eyes of four patients and occurred at an average age of 20 years, which was 14% of patients studied. Peripheral tractional RD was seen in 25% of all eyes and in 55% of eyes of patients older than 45 years.[6] In the Japanese family studied by Miyamoto et al., RDs were observed in three eyes of three patients out of a total of eleven family members studied and one of these was a tractional RD. Age at which these RDs occurred was not specified.[3] However, in the French family studied by Brézin et al., nine out of twelve family members studied had RDs. These occurred primarily in childhood and adolescence, with the median age of occurrence being age 8. The earliest RD was observed at age 3 and the latest RD recorded was at age 33.[5]

Medical therapy

Patients with Wagner syndrome should have ophthalmologic examination at least annually by a vitreoretinal specialist. Glasses or contact lenses can be used to correct refractive error.[1]

Evaluation of family

Due to the variable expressivity of Wagner syndrome, the immediate family of any patient newly diagnosed with Wagner syndrome should be thoroughly evaluated because they could have a less clinically severe form of the syndrome that has not been noticed previously.

Most patients with Wagner syndrome have an affected parent but de novo mutations can occur. In the case of a patient with a supposed de novo mutation resulting in Wagner syndrome, the patient’s parents should both be evaluated with an ophthalmologic examination and molecular genetic testing. Risk of the patient’s siblings having or developing Wagner syndrome is directly related to the genetic status of parents as Wagner syndrome is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern. If a VCAN mutation is found in one the parents, the risk of siblings inheriting is 50%. If a VCAN mutation is not found in either parent, then risk of the siblings having or developing Wagner syndrome is low but higher than in the general population due to the possibility of germline mosaicism in the parents.

Risk of a patient’s offspring having Wagner syndrome is 50% since it is caused by an autosomal dominant mutation. Genetic counseling is appropriate to offer to patients planning to have children, preferably before pregnancy.[1]

Surgery

Surgical intervention in a patient with Wagner syndrome is much the same as in a patient without Wagner syndrome. Cataracts that cause significant impairment are removed and replaced with an intraocular lens implant. Graemiger et al. suggest that cataract extraction be performed in with extracapsular techniques to prevent the development of iris neovascularization and neovascular glaucoma. They reported 20% of patients who had intracapsular cataract extraction developed iris neovascularization as compared to none who had extracapsular cataract extraction.[6]

Laser retinopexy or cryotherapy can be used to treat retinal breaks without detachment. Retinal detachment, retinal traction involving the macula, or epiretinal membranes are indications for retinal surgery.[1]

Most retinal detachments in Wagner syndrome are rhegmatogenous and repair is mainly focused on closing the retinal breaks via pars plana vitrectomy or retinal pneumopexy. Tractional retinal detachment is secondary to shortening of the membranes connected to the retina. Surgical repair of a tractional retinal detachment includes removal of the membranes and vitreoretinal adhesions. Often, retinotomies are needed to relieve the traction.[1]

Complications

If a posterior capsule opacification occurs post-cataract surgery, it is removed with YAG laser capsulotomy.[1]

It is uncertain if patients with Wagner syndrome are at higher risk for retinal detachment after cataract surgery because the majority of studies on Wagner syndrome focus on the clinical findings or genetics of the syndrome. Cataract extraction and intraocular lens implantation were performed on patients in several studies and no complication of retinal detachment was recorded.[4][5][6]

Some common complications of pars plana vitrectomy for repair of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment include new retinal breaks, proliferative vitreoretinopathy (PVR), and new macular holes. In patients with recurrent breaks, silicon oil or gas injection is often necessary.[16]

Prognosis

Prognosis of Wagner syndrome is variable depending on disease severity but is thought to be moderate. Some patients experience severe vision loss but others can retain useful vision throughout their life.[17]

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 1.23 Kloeckener-Gruissem B, Amstutz C. VCAN-Related Vitreoretinopathy. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, et al., editors. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK3821/.

- ↑ https://www.orpha.net/consor/cgi-bin/OC_Exp.php?Lng=GB&Expert=898

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 Miyamoto T, Inoue H, Sakamoto Y, et al. Identification of a novel splice site mutation of the CSPG2 gene in a Japanese family with Wagner syndrome. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46(8):2726-2735. doi:10.1167/iovs.05-0057.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Meredith SP, Richards AJ, Flanagan DW, Scott JD, Poulson AV, Snead MP. Clinical characterisation and molecular analysis of Wagner syndrome. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91(5):655-659. doi:10.1136/bjo.2006.104406.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 5.8 Brézin AP, Nedelec B, Barjol A, Rothschild PR, Delpech M, Valleix S. A new VCAN/versican splice acceptor site mutation in a French Wagner family associated with vascular and inflammatory ocular features. Mol Vis. 2011;17:1669-1678.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 Graemiger RA, Niemeyer G, Schneeberger SA, Messmer EP. Wagner vitreoretinal degeneration. Follow-up of the original pedigree. Ophthalmology. 1995;102(12):1830-1839. doi:10.1016/s0161-6420(95)30787-7.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Keller KE, Kelley MJ, Acott TS. Extracellular matrix gene alternative splicing by trabecular meshwork cells in response to mechanical stretching. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48(3):1164-1172. doi:10.1167/iovs.06-0875.

- ↑ Brown DM, Graemiger RA, Hergersberg M, et al. Genetic linkage of Wagner disease and erosive vitreoretinopathy to chromosome 5q13-14. Arch Ophthalmol. 1995;113(5):671-675. doi:10.1001/archopht.1995.01100050139045.

- ↑ Kloeckener-Gruissem B, Bartholdi D, Abdou MT, Zimmermann DR, Berger W. Identification of the genetic defect in the original Wagner syndrome family. Mol Vis. 2006;12:350-355. Published 2006 Apr 17..

- ↑ Mukhopadhyay A, Nikopoulos K, Maugeri A, et al. Erosive vitreoretinopathy and wagner disease are caused by intronic mutations in CSPG2/Versican that result in an imbalance of splice variants. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47(8):3565-3572. doi:10.1167/iovs.06-0141.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Thomas AS, Branham K, Van Gelder RN, et al. Multimodal Imaging in Wagner Syndrome. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2016;47(6):574-579. doi:10.3928/23258160-20160601-10.

- ↑ Rothschild PR, Burin-des-Roziers C, Audo I, Nedelec B, Valleix S, Brézin AP. Spectral-Domain Optical Coherence Tomography in Wagner Syndrome: Characterization of Vitreoretinal Interface and Foveal Changes. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015 Nov;160(5):1065-1072.e1

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Rothschild PR, Burin-des-Roziers C, Audo I, Nedelec B, Valleix S, Brézin AP. Spectral-Domain Optical Coherence Tomography in Wagner Syndrome: Characterization of Vitreoretinal Interface and Foveal Changes. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;160(5):1065-1072.e1. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2015.08.012.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Bleicher ID, Garg I, Hoyek S, Place E, Miller JB, Patel NA. Widefield Swept-Source Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography Findings in Wagner Syndrome. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2022 Aug 11.

- ↑ Rothschild PR, Burin-des-Roziers C, Audo I, Nedelec B, Valleix S, Brézin AP. Spectral-Domain Optical Coherence Tomography in Wagner Syndrome: Characterization of Vitreoretinal Interface and Foveal Changes. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015 Nov;160(5):1065-1072.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2015.08.012. Epub 2015 Aug 15. PMID: 26284746.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Sung JY, Lee MW, Won YK, Lim HB, Kim JY. Clinical characteristics and prognosis of Total Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment: a matched case-control study. BMC Ophthalmol. 2020;20(1):286. Published 2020 Jul 13. doi:10.1186/s12886-020-01560-4.

- ↑ https://www.orpha.net/consor/cgi-bin/OC_Exp.php?Lng=GB&Expert=898