Lattice Degeneration

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Introduction

Lattice degeneration is a common peripheral retinal degeneration that is characterized by localized retinal thinning, overlying vitreous liquefaction, and marginal vitreoretinal adhesion. The condition is associated with atrophic retinal holes, retinal tears, and retinal detachments. Lattice degeneration is a common condition that can be found in 6-8% of the general population[1] though past histologic studies on autopsy suggest a prevalence as high as 10.7% [2]

Risk Factors

Lattice degeneration is most commonly found incidentally on routine ophthalmic examination. However, several classic associations exist:

- Myopia: The prevalence of lattice degeneration is greater in myopic eyes (33% in one study) compared to the general population (around 6-10%), which might at least partially explain the increased risk of retinal detachment in myopes.[3]

- Retinal Detachment: Approximately 20 to 30% of patients with a rhegmatogenous retinal detachment (RRD) have lattice degeneration. However, and importantly, the reverse is quite different: few eyes with lattice degeneration actually develop retinal detachments. In one study, three out of 423 eyes (0.7%) with lattice degeneration developed clinical retinal detachments and sixteen (3.7%) developed subclinical retinal detachments. Nonetheless, lattice degeneration is frequently cited as a risk factor for development of RRD given its strong association with this entity.[1][2][4]

- Hereditary Vitreopathies: Stickler Syndrome may present with unique radial perivascular lattice-like degeneration. [5] This feature is not believed to be congenital, but rather, develops during childhood and progresses throughout life. Wagner Syndrome may also present with lattice degeneration.[6]

Etiology

The etiology of lattice degeneration is unknown, though theories include developmental anomalies of the internal limiting membrane, embryologic vascular anastomosis, localized retinal ischemia, or the contention that it is a primary vitreopathy leading to the formation of abnormal vitreous traction.[2][7]

Postmortem histologic studies of lattice lesions have exhibited three invariable findings[2][8]:

- Retinal thinning

- Vitreous liquefaction overlying the thinned retina

- Tight vitreoretinal adhesion at the margins of the lesion

Electron microscopic studies of lattice lesions demonstrated presence of the following features[2][8][9]:

- Retinal thinning

- Vascular fibrosis

- Neuronal atrophy

- Accumulation of glial material

- Pigmentary changes

- Internal limiting membrane changes

- Lack of basement membrane over the surface of lattice lesions and replacement with glial cells.

Pathophysiology

It is well documented that lattice degeneration increases the risk of retinal tears or subsequent retinal detachments. This occurs via two mechanisms: (1) atrophic retinal hole or (2) retinal tear.

Atrophic Retinal Hole

Atrophic round holes occur within the substance of the lattice lesion and likely represent the end-stage of retinal thinning and subsequent dissolution of tissue. [2] These holes rarely progress to a clinical retinal detachment though may develop a small cuff of subretinal fluid stemming from the overlying liquefied vitreous. As this cuff typically remains stable over time, it is believed that the overlying liquid vitreous does not communicate with the greater vitreous body.[2] Overall, a small percentage of retinal detachments are caused by lattice degeneration with atrophic holes (2.8% from one study).[10] And conversely, the risk of a retinal detachment developing in a patient with lattice degeneration associated with atrophic hole has been estimated to be less than 0.3%.[2] Interestingly, these retinal detachments occur more frequently in young, myopic patients, an observation possibly explained by the progressive strengthening of the bond between the retina and retinal pigment epithelium at the border of the hole with time.[2]

Retinal Tear

Retinal tears are believed to stem from traction at the margins of lattice lesions, an area typified by tight vitreoretinal adhesion. This traction may originate from a posterior vitreous detachment, and as such, the retinal tear is often on the posterior margin of the lattice lesion. However, not all retinal tears occurring in eyes with lattice degeneration occur adjacent to a lattice lesion, suggesting that these eyes may be at a generalized increased risk of retinal tears. Estimates for the percentage of tears that do occur adjacent to lattice lesions range widely, from to 28% to 82.5% [2] Overall, the risk of retinal tear occurring adjacent to a lattice lesion is very low, with one study suggesting a 1% incidence after 10 years.[11]

Retinal Detachment

As mentioned previously, approximately 20 to 30% of patients with retinal detachment have evidence of lattice degeneration. Detachments associated with lattice degeneration more commonly occur due to retinal tears (16 to 18%) compared to atrophic round holes (range of 2.8 to 13.9%).[2][12][10] Studies measuring the converse (i.e., the risk of a retinal detachment developing in a patient with lattice degeneration though not necessarily from a lattice lesion-associated retinal break) have shown a fairly low overall risk ranging from 0.3 to 0.5%.[13]

Clinical Information

History

Patients with lattice degeneration are generally asymptomatic, and it is typically incidentally discovered. However, some patients may present with symptoms of sequelae, such as retinal tear or detachment. These symptoms may include photopsias, floaters, peripheral visual field loss, and/or loss of vision.

The long term chance of retinal detachment in patients with lattice is around 0.5%to 0.7%.[2][14] On the other hand, one-third to 40% of patients with retinal detachments, without compounding factors such as surgery or other conditions, have been reported to have lattice.[2][15]

Examination

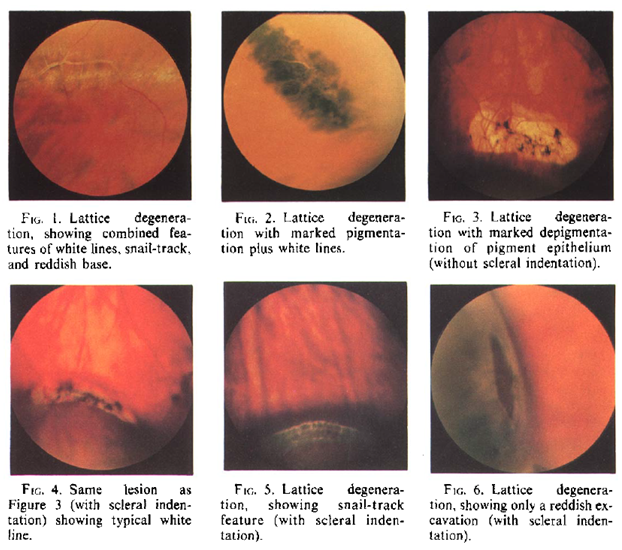

A comprehensive ophthalmic exam is necessary for the purposes of identifying lattice lesions and differentiating them from retinal breaks or other pathologic findings. One important misconception about the clinical diagnosis of lattice degeneration is the prerequisite of lattice lines, a topic addressed by Dr. Norman Byer. Simply put: lattice lines are NOT required for the diagnosis of lattice degeneration. Dr. Byer resolves the matter succinctly, suggesting that any lesion whose borders demonstrate an "abrupt, discrete irregularity of the otherwise smooth surface of the retina" should be regarded as lattice degeneration, despite the great variety in morphologic features.[2]

Nonetheless, typical findings of lattice degeneration include one or more of the following features organized in accordance to their presumed frequency of occurrence:

- Localized round, oval or linear shaped retinal thinning

- Pigmentation

- Whitish-yellow surface flecks

- Round, oval or linear white patches

- Round, oval or linear red craters

- Small atrophic round holes

- Branching white lines

- Yellow atrophic spots (depigmentation of pigment epithelium)

- Rarely, tractional tears at the ends or posterior margins of lesions.

Usually one, but sometimes two or more of these features predominate in each individual lesion. Again, presence of white lines is not necessary for the diagnosis of lattice degeneration.[2] The so-called snailtrack degeneration, which has a snowflake-like appearance on its surface, was considered to be a variant of lattice degeneration by Dr. Normal Byer.[2]

The observation of lesions in the peripheral retina suggestive of lattice must be carefully examined with scleral indentation and indirect ophthalmoscopy. The borders of lattice lesions will have an abrupt, discrete edge adjacent to otherwise normal retina.

Examples of various lattice lesions are shown below.[2]

Diagnosis

Lattice degeneration is a clinical diagnosis, identified on dilated fundus examination typically using a binocular indirect ophthalmoscope, with or without the use of scleral depression. Ancillary imaging may assist in identifying and documenting lattice degeneration. Conventional fundus cameras or wide-field imaging may be used for this purpose.

The clinical appearance of lattice is classically variable and may present as multiple morphologies in the same patient. Other conditions to consider that may appear similar in appearance include cobblestone (paving stone) degeneration, retinoschisis, atrophic holes, chorioretinal scarring, congenital hypertrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium, or other Peripheral Retinal Degenerations, most notably white without pressure or cystoid degeneration.

Management

Prevention

There are no measures to prevent the development of lattice degeneration.

Treatment

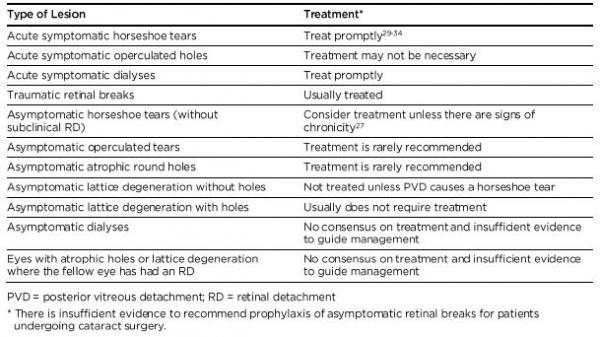

There is no mandatory treatment for lattice degeneration alone. While it is associated with retinal holes, tears and detachments, it is not generally advocated to treat lattice lesions on a solely prophylactic basis.

Medical

There is currently no medical treatment for this condition.

Surgical

A simplified recommendation for treatment of peripheral retinal lesions according to the preferred practice pattern is shown below and is available at https://www.aao.org/preferred-practice-pattern/posterior-vitreous-detachment-retinal-breaks-latti[1]

Laser photocoagulation is the preferred treatment for lattice lesions at risk for retinal tears/detachment. Based on the risk for future tears or detachments, practitioners may decide to treat with other modalities such as cryotherapy or scleral buckling depending on their assessment of retinal detachment risk.

Prognosis

The prognosis for lattice degeneration in itself is good. The vast majority of patients will have lesions that are completely stable or slowly progressive. Patients who develop retinal tears, detachments, and subsequent vitreoretinal traction should be treated as those conditions arise. Eyes with lattice (with or without holes) are at very low risk for retinal detachment overall. Eyes which develop retinal tears, especially following a posterior vitreous detachment, are at risk for retinal detachment and require laser photocoagulation or cryotherapy to treat the horseshoe tear(s). [16][17]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 American Academy of Ophthalmology. AAO PPP Retina/Vitreous Committee, Hoskins Center for Quality Eye Care. Preferred Practice Pattern: Posterior Vitreous Detachment, Retinal Breaks, and Lattice Degeneration PPP 2019. October 2019 revision. Available at: https://www.aao.org/preferred-practice-pattern/posterior-vitreous-detachment-retinal-breaks-latti. Accessed 21st April 2020.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 Byer NE. Lattice degeneration of the retina. Surv Ophthalmol. Jan-Feb 1979;23(4):213-48.

- ↑ Celorio JM, Pruett RC. Prevalence of lattice degeneration and its relation to axial length in severe myopia. Am J Ophthalmol. 1991;111(1):20–23. doi:10.1016/s0002-9394(14)76891-6

- ↑ Byer NE. Subclinical retinal detachment resulting from asymptomatic retinal breaks: prognosis for progression and regression. Ophthalmology. 2001 Aug;108(8):1499-503; discussion 1503-4. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(01)00652-2. PubMed PMID: 11470709.

- ↑ Parma ES, Körkkö J, Hagler WS, Ala-Kokko L. Radial perivascular retinal degeneration: a key to the clinical diagnosis of an ocular variant of Stickler syndrome with minimal or no systemic manifestations. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002 Nov;134(5):728-34.

- ↑ Zech JC, Morlé L, Vincent P, Alloisio N, Bozon M, Gonnet C, Milazzo S, Grange JD, Trepsat C, Godet J, Plauchu H. Wagner vitreoretinal degeneration with genetic linkage refinement on chromosome 5q13-q14. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1999 May;237(5):387-93.

- ↑ Lewis H. Peripheral retinal degenerations and the risk of retinal detachment. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003 Jul;136(1):155-60. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(03)00144-2. Review.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Straatsma BR, Zeegen PD, Foos RY, et al: Lattice degeneration of the retina. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol 78:87-113, 1974.

- ↑ Streeten BW, Bert M: The retinal surface in lattice degeneration of the retina. Am J Ophthalmol 74:1201-1209, 1972.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Tillery WV, Lucier AC. Round atrophic holes in lattice degeneration--an important cause of phakic retinal detachment. Trans Sect Ophthalmol Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1976 May-Jun;81(3 Pt 1):509-18.

- ↑ Byer NE. Changes in and prognosis of lattice degeneration of the retina. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1974 Mar-Apr;78(2):OP114-25.

- ↑ Morse PH, Scheie HG. Prophylactic cryoretinopexy of retinal breaks. Arch Ophthalmol. 1974 Sep;92(3):204-7.

- ↑ OKUN E. Gross and microscopic pathology in autopsy eyes. III. Retinal breaks without detachment. Am J Ophthalmol. 1961 Mar;51:369-91.

- ↑ Byer NE. Long-term natural history of lattice degeneration of the retina. Ophthalmology. 1989;96(9):1396–1402. doi:10.1016/s0161-6420(89)32713-8

- ↑ Burton TC: The influence of refractive erro and lattice degeneration on the incidence of retinal detachment. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 87: 143-157, 1989.

- ↑ Byer NE. Rethinking prophylactic therapy of retinal detachment. In: Stirpe M, ed. Advances in Vitreoretinal Surgery. New York, NY: Ophthalmic Communications Society; 1992:399-411.

- ↑ Byer NE. Long-term natural history of lattice degeneration of the retina. Ophthalmology. 1989;96(9):1396-1401; discussion 1401-1392.