Orbital Aspergillosis

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Disease

Orbital aspergillosis

- ICD-10-CM B44.9 Aspergillosis, unspecified

- ICD-9-CM 117.3 Aspergillosis

Etiology

Aspergillosis and mucormycosis are the most common orbital fungal infections, while aspergillosis is the most common cause of paranasal mycoses. [1] Orbital mycoses typically occurs via extension from the paranasal sinuses, however, organisms can also gain access to the orbit from direct trauma or hematogenous spread from distant sites.[2]

Risk Factors

Orbital aspergillosis occurs primarily in immunocompromised hosts, but infections in immunocompetent patients are well-documented.[3][4] One major risk factor for orbital involvement is paranasal mycosis, but other risk factors include diabetic ketoacidosis, neutropenia, neutrophil dysfunction, prosthetic devices, trauma, severe burns, alcoholism, intravenous drug use, HIV infection, hematologic malignancy, bone marrow transplantation, liver cirrhosis, corticosteroid use, antibiotics, and chemotherapy. Smoking contaminated marijuana has also been reported to increase the risk for development of sino-orbital aspergillosis in immunocompromised patients.[5]

Another important consideration is environmental exposure, such as to construction or demolition sites, from compost, and in endemic areas, such as Sudan and Saudi Arabia. For example, aspergilloma (ie “fungus ball”) is the leading cause of proptosis in Sudan.[6][7]

General Pathology

Aspergillosis is caused by the genus Aspergillus, which is a spore-forming, septate filamentous mold (See Figure 3). The two species, Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus fumigatus, most commonly affect the orbit. Aspergillus thrives in warm, moist environments and often colonizes the respiratory tract without causing disease in immunocompetent individuals.

Orbital aspergillosis is divided into invasive and noninvasive forms with the former more common in immunocompromised patients. [6]

- INVASIVE:

- Invasive aspergillosis is characterized by bone invasion or fungal tissue behaving similar to an inflammatory or malignant process.[8] This can present in a variety of ways, from a localization process to a fulminant one. As a localized process, it can invade nearby structures and/or blood vessels, causing thrombosis and tissue necrosis. As a fulminant process, there is embolization and multiorgan involvement, sometimes leading to death.[4]

- NONINVASIVE:

- In contrast, noninvasive aspergillosis typically does not have fungal infiltration of tissue, though there can be tissue destruction secondary to a chronic inflammatory reaction. For example, allergic aspergillus sinusitis occurs in young, atopic individuals, who often have a history of recurrent sinusitis, nasal congestion, or allergic rhinitis. It is a chronic sinus disease that often leads to accumulation of a thick material known as allergic mucin. This mucin consists of degenerated eosinophils, cellular debris, and Charcot-Leyden crystals (slender, birefringent needles of uniform shape but of variable length and width, consisting of two hexagonal pyramids joined base to base) and can necessitate debridement.[7][9]

- Another example of noninvasive aspergillosis is the sinonasal aspergilloma, also known as “fungus ball” seen primarily in immunocompetent patients. Of note, in immunocompromised patients, this can become invasive.[6][9] Sinonasal fungus balls are extramucosal, mycotic proliferations that fill at least one paranasal sinus, usually the sphenoid or ethmoid. Patients typically present with nasal symptoms, such as rhinorrhea or obstruction, and retro- or peri-orbital headaches. Occasionally, vision loss is reported if the fungus ball is compressing the optic nerve.[10] If the fungus ball is located in the posterior sphenoid or ethmoid sinus, a rare neuro-ophthalmic emergency called orbital apex syndrome (OAS) may present. Orbital apex syndrome presents with visual loss, ophthalmoplegia, and ptosis. Early recognition and management with antifungals and/or sinus surgery are imperative to prevent permanent vision loss.[11]

Pathophysiology

Primary orbital aspergillosis is a rare entity, but it has been reported in the literature.[3] Orbital aspergillosis most commonly occurs as a result of contiguous spread from the paranasal sinuses with sinus disease being present in the majority of those affected. Inhalation of fungal spores in the nasopharynx and paranasal sinuses in an immunocompromised host can then initiate a granulomatous reaction that can extend to the orbit.[12] Secondary involvement can also result from trauma or hematogenous spread.

Primary Prevention

Prevention is targeted to those who are at higher risk of infection, including patients with a history of HIV/AIDS, organ transplantation, chronic chemotherapy, or hematologic malignancies. Certain populations may benefit from prophylactic antifungal therapy, but this is not standardized. Some suggest prevention in endemic areas or hospital construction zones by using masks and air supply treatment.[13] Increased awareness among healthcare providers is also integral in prevention and recognition.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of orbital aspergillosis is based on a combination of clinical presentation, imaging, and biopsy.

History

The clinical history of orbital aspergillosis is nonspecific and can closely resemble several orbital inflammatory and neoplastic conditions (see differential diagnosis).[3] Because it depends on the immune status of the patient and the form of aspergillosis, the presentation is typically chronic and indolent in immunocompetent patients and more acute and progressive in immunocompromised patients. The most common chief complaints at presentation are pain, headache, and/or proptosis.[4][14][15] The description of the pain is often vague, usually in the retrobulbar area. Pain usually precedes ophthalmic findings and can become progressively severe. Patients with allergic fungal sinusitis commonly have a history of allergic rhinitis, nasal congestion, nasal polyps, or recurrent sinusitis and may not initially present with orbital signs or symptoms.

Physical Examination

A full orbital and ophthalmology examination should be performed, including best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA), color vision, formal visual field evaluation, pupillary function, extraocular motility range and presence of pain, facial sensation, intraocular pressure, slit lamp biomicroscopy, dilated fundus exam, orbital auscultation, and exophthalmometry. This should be supplemented with nasal and sinus examination and may include otorhinolaryngology consultation.[6]

Signs

Clinical signs of orbital aspergillosis are highly variable and dependent on the disease entity. Involvement of the orbit can be primarily orbital, sino-orbital, or with central nervous system involvement.[4]

Acute invasive sino-orbital aspergillosis may present with signs characteristic of a bacterial cellulitis with periorbital inflammation that progresses to an orbital apex syndrome, presenting with ptosis, proptosis, painful ophthalmoplegia, and an optic neuropathy. Proptosis can also be seen in noninvasive aspergillosis secondary to expansion of the sinus cavities. Fulminant aspergillosis can resemble mucormycosis with invasion into the blood vessels with subsequent thrombosis and tissue necrosis with a black eschar in late stages. Alteration in mental status may suggest central nervous system invasion or indicate the presence of a contributing risk factor, like diabetic ketoacidosis.[13]

Symptoms

The most common presenting symptom of orbital aspergillosis is orbital and facial pain. Concomitant sinus involvement with congestion, rhinorrhea, epistaxis, and epiphora is often, but not always, present and contributes to the diagnostic challenges of this disease. Allergic fungal sinusitis patients do not usually present with orbital symptoms, but rather with symptoms of allergic rhinitis, chronic sinusitis and nasal obstruction.[8] Patients with aspergillomas may present with facial pain or symptoms secondary to chronic sinusitis. Invasive aspergillosis patients may present acutely or over a period of weeks to months and may report a wide range of symptoms including naso-orbital pain, headache, proptosis, epistaxis, and worsening vision.[7]

Diagnostic procedures

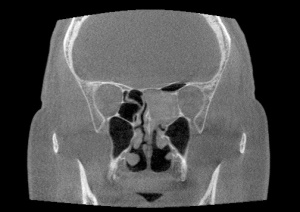

Computed tomography (CT) of the orbit is the initial imaging modality of choice for diagnosing and characterizing the extent of orbital aspergillosis, as it is quick and effective. Aspergillus appears as isodense, heterogenous lesions affecting the paranasal sinuses with calcification and bony erosion. The sphenoid sinus is the most commonly affected paranasal sinus, which is postulated to be related to its low oxygen content and acidic environment (Figures 1 and 2). The presence of patchy hyperattenuation is also considered an indirect indicator of fungal disease.[16] MRI reveals hypointense lesions on T1 and T2-weight images in contrast to neoplastic and bacterial lesions which are hypertense on T-2 weighted images.[8] MRI is generally preferred to CT in evaluating the orbital apex, cavernous sinus, and optic nerve changes.

Incisional biopsy of both the center and periphery of the lesion for histopathology and microbiology is considered the gold standard for diagnosis. Aspergillus has a characteristic microscopic appearance as thin 2-3 𝜇m, septate hyphae with 45 degree branching, best seen on Gomori Methanamine silver and periodic acid Schiff stains (Figure 3).[15] Part of the biopsy should be sent for culture. If initial biopsy does not yield a diagnosis and suspicion remains high, then a second biopsy should be obtained, especially if considering corticosteroids. High rates of negative biopsies have been reported due to a tendency of the fungus to only appear in late-stage samples.[17]

Interest has been growing for non-invasive laboratory based tests for diagnosing aspergillosis. The use of serum assays for galactomannan, an Aspergillus antigen present during fungal growth, may become a useful, noninvasive option to aid in earlier diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis, and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing is a quick and reliable modality which may offer the most sensitive and specific method for identifying Aspergillus infection.[18][19]

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis can be broadly divided into orbital infectious, orbital neoplastic, and orbital non-infectious granulomatous processes.[6]

- Orbital fungal infections: aspergillus, mucor, bipolaris, alternaria, curvularia, coccidioides, blastomyces, histoplasma

- Orbital bacterial infections: preseptal cellulitis, orbital cellulitis, subperiosteal abscess, syphilis, mycobacteria

- Orbital inflammatory disorders: nonspecific orbital inflammation, Graves’ ophthalmopathy, sarcoidosis, polyarteritis nodosa, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, collagen-vascular disorders

- Neoplasia: metastasis, primary tumor, lacrimal gland tumor, lymphoma, leukemia

- Vascular disease: carotid-cavernous fistula, cavernous sinus thrombosis, varix

- Neuro-ophthalmic disorders: optic neuritis, optic neuropathy, cranial neuropathy

Management

General treatment

Management of aspergillosis consists of reversal of any immunosuppression, aeration and drainage of the paranasal sinuses involved, and treatment with systemic antifungals. Retrobulbar injection of amphotericin B can be considered.[20] [21] Surgical debridement of the orbit, sinuses and skull base with intravenous and local irrigation of antifungals may indicated for widespread invasive disease.[22] Unfortunately, orbital exenteration is occasionally necessary at the time of orbital debridement if severe retrobulbar or apical involvement is encountered, but this is growing increasingly unnecessary.[23]

Treatment of allergic aspergillosis involves surgical debridement of the involved sinuses concurrent with administration of systemic and topical corticosteroids. Systemic antifungals are not indicated unless the patient is immunocompromised.[24] In addition, patients with allergic aspergillosis may have nasolacrimal duct obstruction requiring surgical intervention in the future.

Similarly, management of Aspergilloma involves surgical debridement and aeration of the sinus involved without the need for antifungal therapy.[25]

Medical therapy

Intravenous amphotericin B is considered the gold standard for medical treatment of sino-orbital aspergillosis. A lipid formulation of amphotericin B is available for patients with impaired renal function. Oral itraconazole is also commonly used as an alternative to or in combination with amphotericin B.[26] Oral voriconazole has also been shown to be equally effective as primary therapy with fewer side effects.[27] The maximum daily dosage of the chosen antifungal agent(s) is used until the disease is controlled, which is then followed by maintenance therapy with oral itraconazole.[28] Newer classes of antifungals such as lipid complex nystatin and echinocandins are starting to be used more widespread.

Medical follow up

A multi-disciplinary approach is often necessary, involving oculoplastic surgery, otolaryngology, ophthalmology , infectious disease, and neurosurgery.

Complications

Complications include optic neuropathy, brain abscess, cavernous sinus thrombosis, mycotic aneurysms with subsequent subarachnoid hemorrhage, meningitis, and death.[29][30]

Prognosis

The prognosis of invasive aspergillosis is significantly worse than the prognosis of other forms of sinus aspergillosis and mortality rate remains high, especially in the setting of cerebral involvement. A recent study reported a mortality rate of 40% associated with invasive orbital aspergillosis and 50% with CNS involvement.[22] This is thought to be due to invasion of bone and blood vessel walls which make surgical access and drug penetration challenging. Delayed diagnosis, initial treatment with corticosteroids, fever, intracranial extension, and demonstration of hyphal invasion on histopathology have been associated with a poorer prognosis.[15][22] With advancements in medical management there has been an overall improvement in disease control and survival.

References

- ↑ Chakrabarti A, Sharma SC, Chander J. Epidemiology and pathogenesis of paranasal sinus mycoses. Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 1992;107(6_part_1):745-750.

- ↑ Klotz SA, Penn CC, Negvesky GJ, Butrus SI. Fungal and Parasitic Infections of the Eye. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2000;13(4):662-685.

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.0 3.1 3.2 Aggarwal E, Mulay K, Menon V, Sundar G, Honavar SG, Sharma M. Isolated Orbital Aspergillosis in Immunocompetent Patients: A Multicenter Study. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 2016;165:125-132.

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Mody KH, Ali MJ, Vemuganti GK, Nalamada S, Naik MN, Honavar SG. Orbital aspergillosis in immunocompetent patients. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 2014;98(10):1379-1384.

- ↑ Johnson TE. Sino-orbital Aspergillosis in Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome. Archives of Ophthalmology. 1999;117(1):57.

- ↑ Jump up to: 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Levin LA, Avery R, Shore JW, Woog JJ, Baker AS. The spectrum of orbital aspergillosis: a clinicopathological review. Survey of Ophthalmology. 1996;41(2):142-154.

- ↑ Jump up to: 7.0 7.1 7.2 Kirszrot J, Rubin PAD. Invasive Fungal Infections of the Orbit. International Ophthalmology Clinics. 2007;47(2):117-132.

- ↑ Jump up to: 8.0 8.1 8.2 Mukherjee B, Raichura N, Alam M. Fungal infections of the orbit. Indian Journal of Ophthalmology. 2016;64(5):337.

- ↑ Jump up to: 9.0 9.1 Slavin ML. Primary Aspergillosis of the Orbital Apex. Archives of Ophthalmology. 1991;109(11):1502.

- ↑ Chen B-N, Chang K-M. Sphenoid sinus fungus ball presenting with bilateral visual disturbance. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2018;11(11):12763-12767.

- ↑ Cho SH, Jin BJ, Lee YS, Paik SS, Ko MK, Yi H-J. Orbital Apex Syndrome in a Patient with Sphenoid Fungal Balls. Clinical and Experimental Otorhinolaryngology. 2009;2(1):52.

- ↑ Stevens DA, Kan VL, Judson MA, et al. Practice Guidelines for Diseases Caused by Aspergillus. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2000;30(4):696-709.

- ↑ Jump up to: 13.0 13.1 Ribes JA, Vanover-Sams CL, Baker DJ. Zygomycetes in Human Disease. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2000;13(2):236-301.

- ↑ Khan AR, Dutta U. Orbital Aspergillosis A Rare Case of Proptosis. Asian Pacific Journal of Health Sciences. 2018;5(4):39-42.

- ↑ Jump up to: 15.0 15.1 15.2 Sivak-Callcott JA. Localised invasive sino-orbital aspergillosis: characteristic features. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 2004;88(5):681-687.

- ↑ Zinreich SJ, Kennedy DW, Malat J, et al. Fungal sinusitis: diagnosis with CT and MR imaging. Radiology. 1988;169(2):439-444.

- ↑ Mauriello JA, Yepez N, Mostafavi R, et al. Invasive Rhinosino-orbital Aspergillosis with Precipitous Visual Loss. Ophthalmic Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery. 1997;13(4):293.

- ↑ Pinel C, Fricker-Hidalgo H, Lebeau B, et al. Detection of Circulating Aspergillus fumigatus Galactomannan: Value and Limits of the Platelia Test for Diagnosing Invasive Aspergillosis. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2003;41(5):2184-2186.

- ↑ Singh R, Singh G, Urhekar A. Detection of Aspergillus Species by Polymerase Chain Reaction. International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences. 2016;5(10):254-260.

- ↑ Mainville N1, Jordan DR. Orbital apergillosis treated with retrobulbar amphotericin B. Orbit. 2012 Feb;31(1):15-7. doi: 10.3109/01676830.2011.603596. Epub 2011 Oct 26.

- ↑ Hirabayashi KE1, Kalin-Hajdu E, Brodie FL, Kersten RC, Russell MS, Vagefi MR. Retrobulbar Injection of Amphotericin B for Orbital Mucormycosis. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017 Jul/Aug;33(4):e94-e97. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000000806.

- ↑ Jump up to: 22.0 22.1 22.2 Choi HS, Choi JY, Yoon JS, Kim SJ, Lee SY. Clinical Characteristics and Prognosis of Orbital Invasive Aspergillosis. Ophthalmic Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery. 2008;24(6):454-459.

- ↑ Swoboda H, Ullrich R. Aspergilloma in the frontal sinus expanding into the orbit. J Clin Pathol. 1992;45:629–30. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/jcp.45.7.629.

- ↑ Carter KD, Graham SM, Carpenter KM. Ophthalmic manifestations of allergic fungal sinusitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1999;127:189–95.

- ↑ Klapper SR, Lee AG, Patrinely JR, Stewart M, Alford EL. Orbital involvement in allergic fungal sinusitis. Ophthalmology. 1997;104:2094–100.

- ↑ Massry GG, Hornblass A, Harrison W. Itraconazole in the Treatment of Orbital Aspergillosis. Ophthalmology. 1996;103(9):1467-1470.

- ↑ Herbrecht R, Denning DW, Patterson TF, Bennett JE, Greene RE, Oestmann JW, et al. Voriconazole versus amphotericin B for primary therapy of invasive aspergillosis. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:408–15

- ↑ Stevens DA, Kan VL, Judson MA, et al. Practice Guidelines for Diseases Caused by Aspergillus. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2000;30(4):696-709.

- ↑ Hedges TR, Leung L-SE. Parasellar and orbital apex syndrome caused by aspergillosis. Neurology. 1976;26(2):117-117.

- ↑ Baeesa SS, Bakhaidar M, Ahamed NA, Madani TA. Invasive Orbital Apex Aspergillosis with Mycotic Aneurysm Formation and Subarachnoid Hemorrhage in Immunocompetent Patients. World Neurosurgery. 2017;102:42-48.