Squamous Carcinoma of the Eyelid

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma (SCC) of the eyelid is malignant epidermal carcinoma. SCC is the second most common eyelid malignancy, accounting for less than 5% of malignant eyelid neoplasms. Basal cell carcinoma is up to 40 times more common than SCC.

Disease Entity

International Classification of Disease (ICD)

Diagnosis Code from ICD-10 Version 2017 : C44.329

Short Description: Squamous cell carcinoma of the eyelid and periocular region

Definition

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), is a type of invasive malignancy arising from the squamous cell layer of the skin epithelium [2]. It can be found in various locations on the body including the skin, anus, cervix, head/neck, vagina, esophagus, urinary bladder, prostate, and lungs. In the ocular and periocular region, it can affect the conjunctiva, cornea, and eyelid skin. It is the second most common malignant eyelid tumor and represents around 5% of malignancies in the palpebral area.[3] It may develop de novo but often may arise from preexisting lesions such as actinic keratosis, squamous cell carcinoma in situ (Bowen's disease), xeroderma pigmentosum, or following radiotherapy.

Etiology

SCC has various risk factors and etiologies [4] including aging [5], longstanding ultraviolet radiation exposure[6], oil derivates and arsenic exposure , cigarette smoke exposure, Human Papilloma Virus infection (HPV), Human Immunodeficiency Virus infection (HIV), xeroderma pigmentosum, actinic keratosis (AK), squamous intraepithelial neoplasia (Bowen's disease), albinism, old burns, chronic ulcers, and immunosuppression.

Epidemiology

Approximately 5% to 10% of all skin cancers occur in the eyelid, and SCC represents 5 -10% of all types of skin cancer in the eyelids. [7]The incidence for eyelid SCC has been reported to be between 0.09 and 2.42 cases per 100 000 population with higher prevalence in males, in the lower lid (especially the medial canthal region), in fair skin, and in countries with high UV light exposure .[8]

Longitudinal studies in the USA and Canada showed that the age-adjusted incidence of SCC has grown by 50% to 200% over the last decades [9]. One study reported the mean age of eyelid SCC diagnosis to be around the 7th and 8th decade of life,[10] although cases can present in much younger individuals.

Orbital invasion has been reported to occur in up to 5.9% of all non-melanoma malignant eyelid carcinomas. Reported rates of metastasis for eyelid SCC vary from 1–21%.[11] Rates of metastasis for cutaneous SCC are better defined and reported at 0.3–3.7%.[12]

It is important to note that cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) is the most common malignancy to develop following solid organ transplantation, with a five-year incidence of 30% in lung transplant recipients and up to 26% in heart transplant recipients [13][14]. The risk of developing SCC varies according to the type of transplant and its associated immunosuppression regimen and requirements. Heart and lungs transplants are associated with a higher risk of SCC compared to renal transplants, [15] because the drugs used to avoid cardiac and pulmonary rejection lead to more profound immunosuppression[16][17]. The amount of time following transplantation is also significant, since longer time intervals following transplantation are associated with a greater cumulative incidence of SCC.[18]

General Pathology

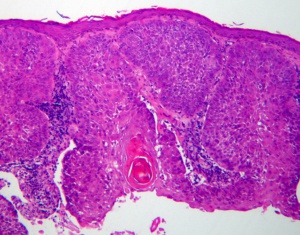

Squamous cell carcinoma is characterized by full thickness atypia with increased mitotic activity of the squamous cells (Figure 1). The tumor may be graded on the amount of dedifferentiation. More differentiated tumors produce keratin. The formation of keratin decreases in less well differentiated tumors and is not seen in poorly differentiated SCC. Nests and strands are also characteristic of well differentiated SCC. However, characteristic intercellular bridges are generally maintained in all SCC (Figure 2).

Diagnosis

History

Suspicious skin lesion in sun exposed skin with actinic keratosis, especially in high risk patients

Previous skin lesions, histopathology, procedures, etc.

Physical examination

Complete ophthalmic examination, including ocular motility and assessment of proptosis

Assessment of entire face and sun exposed areas, facial sensation

Palpation of regional lymph nodes: preauricular, sublingual, submandibular and cervical

Examination of the lesion includes assessment for:

- General appearance of the lesion and periocular skin

- Distortion of eyelid architecture or eyelid malposition

- Presence of skin ulceration

- Madarosis(loss of eyelashes)

- Telangiectasias

Symptoms

- Bleeding

- Pruritus, irritation

- Ulceration

- Pain

- Anesthesia

- Enlarging lesion

- Crusting lesion

Diagnostic procedures

Incisional Biopsy

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis includes any benign or malignant condition of the eyelid skin, including:

Benign

- Seborrheic keratosis

- Actinic keratosis

- Keratoacanthoma

- Chalazion

- Cyst

- Squamous papilloma

- Blepharitis

- Xanthelasma

- Nevus

- Verruca

Malignant

- Basal cell carcinoma

- Sebaceous gland carcinoma

- Malignant melanoma

- Lymphoma

- Merkel cell tumor

- Metastasis

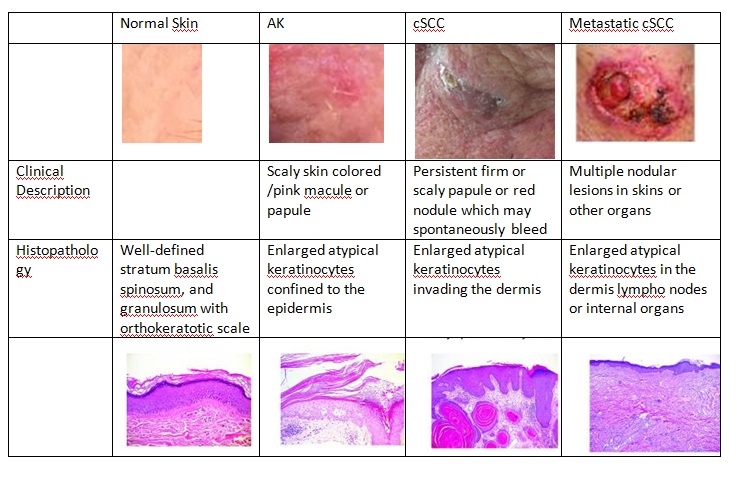

Clinical and pathophysiological features

SCC typically manifests as a spectrum of progressively advancing malignancies, ranging from a precursor actinic keratosis (AK) to squamous cell carcinoma in situ (SCCIS), invasive SCC, and finally metastatic SCC. It is classified as in situ when it is superficial to the basal membrane, and it is considered invasive when it extends deep to the basal membrane layer of the skin. It is also possible to find in the literature others types of skin lesions classified as SCC variants, such as keratoacanthoma and cutaneous horn.

A full thickness biopsy is the gold standard to diagnose SCC as it can determine the depth of invasion and extent of invasion of the cancer. Patients with regional lymph node alterations should undergo Fine Needle Aspiration (FNA) biopsy to determine if cancer cells have spread to these nodes. Invasive SCC is commonly associated with perineural spread.

In situ carcinoma

In situ carcinoma is the term for epithelial lesions in which cells have cytological abnormalities characteristic of malignancy (hyperchromatism, pleomorphism, mitoses) and have lost their typical architecture but lack evidence of local invasion or distant metastases. In the skin, the squamous cell carcinoma in situ (SCCIS) is known as Bowen's disease. It appears as a persistent brown/red spot which may be confused with psoriasis or eczema. There is a strong association of Bowen's disease with HPV (human papilloma virus) infection, mainly type 16[19].

Cutaneous horn

A cutaneous horn (CH) is a lesion with a papular or nodular base and a keratotic cap of various shapes and lengths resembling an animal horn. Usually , it represents hypertrophic solar keratoses. Clinically, CHs vary in size from a few millimeters to several centimeters. The horn may be white, black, or yellowish and can be straight, curved, or spiral in shape. Histologically, there is usually hypertrophic actinic keratosis, SCC in situ, or invasive SCC at the base. Because of the possibility of invasive SCC, a CH should always be excised.

Actinic keratosis

Actinic keratosis is the most common precancerous skin lesion, affecting about 60% of fair-skinned people over the 4th decade of life. Actinic keratosis (AK) appears as a hyperkeratotic lesion. In general, they are round or oval, commonly present in sunlight exposed skin areas, and may or may not have an erythematous base. AK is a direct precursor to squamous cell carcinoma and a risk factor for other skin cancers. Although progression to invasive malignancy is rare, actinic keratoses are squamous cell carcinomas in situ. The main histological feature of actinic keratosis is dysplasia of keratinocytes, or disordered maturation of these cells.

Keratoacanthoma

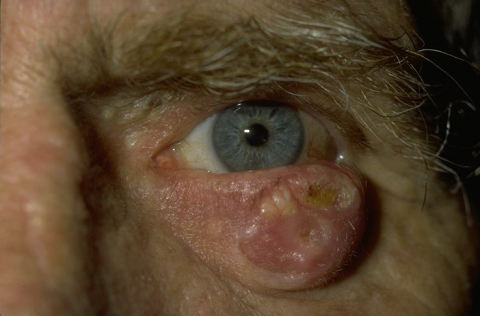

This type of lesion, shown in the figure 3, has recently been classified as a variant of SCC, but there is still a long-standing debate as to whether those lesions are benign reactive lesions or a variant of SCC. Keratoacanthoma typically presents as a cup-shaped nodule with a central keratin crater and elevated, rolled margins. It usually develops over a short period of weeks to a few months and may regress spontaneously[20]. Histopathologically, these dome shaped lesions have thickened epidermis containing islands of well-differentiated squamous epithelium that may be infiltrated by neutrophils surrounding a central mass of keratin. The lesion base is often well-demarcated from the adjacent dermis by inflammatory reaction.

Squamous cell carcinoma

The clinical types of carcinoma are variable and there are no pathognomonic characteristics. The tumor may be clinically indistinguishable from a basal cell carcinoma (BCC), but usually it does not have superficial vascularization, it grows more rapidly, and hyperkeratosis is more frequent. The nodular SCC is characterized by a hyperkeratotic nodule that may develop with the presence of crusts and fissures. The ulcerating SCC (Figure 4) has a red base with well defined, hardened and everted edges. The histopathologic features of SCC depend on the degree of differentiation of the tumor. In well-differentiated tumors, the cells are polygonal with abundant acidophilic cytoplasm and hyperchromatic nuclei with various sizes and staining properties, dyskeratotic cells, and intercellular bridges. Poorly differentiated SCC shows pleomorphism with anaplastic cells, abnormal mitotic figures, little or no evidence of keratinization, and loss of intercellular bridges. Variants of SCC are spindle and adenoid SCC[21].

Pathophysiology

Mutations induced by UVA exposure can perturb multiple cellular pathways which contribute to the formation of cSCC. This type of cancer exhibits impaired genomic maintenance leading to the acquisition of new mutations[22] . The mechanism of genomic instability in keratinocytes likely results from inactivation of p53[23]. Chronic non healings wounds and long standing burn scars may also develop malignant transformation (Marjolin's ulcer). The chronological order of histological changes includes: hyperplasia/hyperkeratosis --> mild to moderate dysplasia, up to severe dysplasia or in situ carcinoma --> invasive SCC.

A clinical, histologic, and molecular comparison of AKs, cSCC, and metastatic cSCC is shown in the figure 5 below.

Adapted from Ratushny, V., Gober, M.D., Hick, R., Ridky, T. W., & Seykora, J. T. (2012). From keratinocyte to cancer: the pathogenesis and modeling of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 122(2), 464–47, Courtesy by: Patricia Lyra M.D. , MSc - Federal University of Espirito Santo, Brazil.

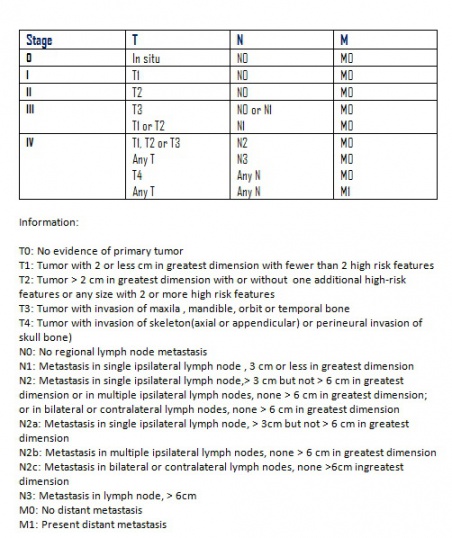

Staging

According to the American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM Staging 7th edition, SCC can be staged as shown below in figure 6 : [24]

T stands for the primary tumor size, location, and invasion level

N stands for nearby lymph node invasion

M is for metastasis

Grade

The cancer’s grade is a predictor of cancer dissemination. The lower the tumor’s grade, the better the prognosis.

| GX | the tumor grade cannot be identified. |

| G1 | well differentiated cells |

| G2 | moderately differentiated cells |

| G3 | poorly differentiated cells. |

| G4 | undifferentiated cells. |

Cancer stage grouping

The stage of an eyelid SCC is given by combining the T, N, M, and G classifications, as shown below:

| Stage 0 | Carcinoma in situ (Tis, N0, M0). |

| Stage IA | The tumor is 5 mm or smaller in diameter or has not invaded the tarsal plate , there is no metastasis to regional lymph nodes or to other areas in the body (T1, N0, M0). |

| Stage IB | The tumor is larger than 5 mm but not more than 10 mm in greatest diameter, or it has invaded the tarsal plate. There is no metastasis to regional lymph nodes or to other areas in the body (T2a, N0, M0). |

| Stage IC | The tumor is between 10 mm and 20 mm in greatest diameter or has spread into the full thickness of the eyelid, but there is no metastasis to regional lymph nodes or to other areas in the body (T2b, N0, M0). |

| Stage II | The tumor is larger than 20 mm in greatest diameter or has spread to nearby parts of the eye, but it has not spread to the regional lymph nodes or to other areas of the body. (T3a, N0, M0). |

| Stage IIIA | The tumor is large enough or has spread enough so that the surgeon will need to remove the eye and nearby structures to get rid of the tumor, but it has not spread to the regional lymph nodes or to other areas of the body (T3b, N0, M0). |

| Stage IIIB | The tumor is of any size and has metastasized to the regional lymph nodes, but not to other areas of the body (any T, N1, M0). |

| Stage IIIC | The tumor has spread outside of the eye, with or without spread to the regional lymph nodes, and cannot be surgically removed due to extensive invasion in structures near the eye. The tumor has not metastasized to distant parts of the body (T4, any N, M0). |

| Stage IV | A tumor of any size has metastasized outside of the eye to distant areas of the body (any T, any N, M1). |

| Recurrent | Recurrent cancer after treatment. It may reoccur in the eye or another part of the body. |

Management

Treatment

Surgical excision is the treatment of choice for SCC and in some cases may require grafts, flaps, or radical surgery. [25] Published reports regarding the treatment of non-melanocytic malignant eyelid tumors show the strongest evidence for complete surgical excision using histology to verify tumor-free margins. Options include Mohs’ micrographic surgery or excision with frozen-section control. [26] However, determining tumor margins clinically may be challenging compared to Basal Cell Carcinoma, as the edges may be less well defined. Patients with large and extensive lesions especially with perineurial invasion and recurrent lesions may benefit from Sentinel Lymph node biopsy with radical dissection as indicated, after ruling out distant metastasis. A high degree of suspicion for orbital invasion along sensory nerves should be maintained. Exenteration may be considered in some patients with orbital involvement and with poor visual potential provided the cavernous sinus is not involved.

Supplemental cryotherapy, topical chemotherapy and irradiation should be applied if the tumor margin is unclear or if there is residual involvement of bulbar conjunctiva .[27]

Cryotherapy

Cryotherapy uses liquid nitrogen at low temperatures to destroy the SCC tissue structure. It is only suitable for AKs and SCCIS and is not suitable for invasive cancers.

It is a safe and low-cost procedure and is very useful in patients with bleeding disorders, those who refuse surgery/ poor surgical candidates, or in patients for whom surgery is contraindicated. The 5 year survival rate for superficial early stage SCCIS can be as high as 95%. The side effects include transient localized pain, swelling, pigmentation changes, loss of hair over hair-bearing areas and blistering.[28]

Photodynamic therapy

In photodynamic therapy, a photosensitizing drug, light, and oxygen are used to induce targeted cell death though apoptosis of cancerous or abnormal tissue. It is suitable for AK and SCCIS. There may be a higher rate of recurrence with this method as compared with surgical excision.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy as the only modality of therapy is only reserved for patients for whom surgery is too risky. Radiation therapy is usually used as an adjunct therapy for patients post-operatively who have disease that has spread to nerves/lymph nodes or cancer with poorly defined margins. Treatment is usually given 3-5 times a week for about 1-2 months.

The side effects include localized hyperemia, erosions, alopecia , localized pain, skin atrophy, pigmentation changes and telangiectasia in the radiation site.

Topical treatment

Topical imiquimod is an immune modulator that is approved to treat genital warts, actinic keratosis, Bowen's disease and superficial SCC. It should be applied 3 times per week for 4-6 weeks. Localized side effects include increased redness, swelling, and erosions or ulcerations. If applied over large areas, it may cause flu-like symptoms. Topical chemotherapy agents like 5-fluorouracil have been used for the treatment of actinic keratosis and SCCIS. It should be applied daily for about a month. It can cause skin irritation and hyperemia over the application area.

Chemotherapy

Systemic chemotherapy is used for advanced SCC that has metastasized to other sites of the body. Recent advances have been made with the advent of Checkpoint inhibitors for extensive and inoperative squamous cell carcinoma and metastatic carcinoma. PD-1 inhibitors (Cemiplimab) has been recently FDA approved for this indication. EGFR inhibitors such as Cetuximab may also be helpful in some patients.[29]

Complications

Misdiagnosis, lack of histologic control, incomplete excision, local tumor recurrence, regional spread metastasis are not uncommon with medical and medicolegal implications.

Follow up and prognosis

SCC can spread to the orbit, lymph nodes or other organs and is more aggressive than BCC. But if SCC of the eyelid is detected early and is completely removed, the prognosis is good. [30]

If malignant orbital invasion is diagnosed, it is appropriate to collaborate with a multidisciplinary team in planning management. Specialists from oncology, radiation oncology, and other disciplines should be involved based on the extent and location of tumor invasion. In general, sunscreens should be used and sun exposure should be reduced. Alcohol and tobacco use should be discouraged. Follow up appointments vary based on the individual case. Any recurrence should be treated aggressively.

Poor prognostic factors include:

- Poorly differentiated tumors

- Perineural spread

- Orbital invasion

- Immunosuppression

Additional Resources

- http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/squamous-cell-carcinoma/DS00924

- http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1212601-overview

References

- ↑ American Academy of Ophthalmology. Squamous Cell Carcinoma. https://www.aao.org/image/squamous-cell-carcinoma-3 Accessed July 17, 2019.

- ↑ Asproudis I, Sotiropoulos G, Gartzios C, Raggos V, Papoudou-Bai A, Ntountas I, Katsanos A, Tatsioni A. Eyelid tumors at the University Eye Clinic of Ioannina, Greece: A 30-year retrospective study. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol 2015;22:230

- ↑ Font RL. Ophthalmic Pathology. An Atlas and Textbook. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1996. Eyelids and lacrimal drainage system; pp. 2229–32.

- ↑ Basti S, Macsai MS. Ocular surface squamous neoplasia: a review. Cornea. 2003;22(7): 687-704.

- ↑ Bessa HJ, Potting MH, Bomfim MG. Neoplasias conjuntivais. Rev Bras Oftalmol. 1997; 56(10):765-7.

- ↑ Palazzi MA, Erwenne CM, Villa LL. Detection of human papillomavirus in epithelial lesions of the conjunctiva. São Paulo Med J. 2000;118(5):125-30

- ↑ Treatment options and future prospects for the management of eyelid malignancies. Cook, Briggs E et al. Ophthalmology , Volume 108 , Issue 11 , 2088 - 2098

- ↑ CookBE, Bartley GB. Epidemiologic characteristics and clinical course of patients with malignant eyelid tumors in an incidence cohort in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Ophthalmology 1999;106:746–50.

- ↑ Gallagher RP, Ma B, McLean DI, et al. Trends in basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and melanoma of the skin from 1973 through 1987. J Am Acad Dermatol 1990;23:413–21.

- ↑ http://www.meajo.org/article.asp?issn=0974-9233;year=2015;volume=22;issue=2;spage=230;epage=232;aulast=Asproudis

- ↑ Loeffler M, Hornblass A. Characteristics and behavior of eyelid carcinoma. Ophthalmic Surg 1990;21:513–18.

- ↑ Kwa RE, Campana K, Moy RL. Biology of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Derm 1992;26:1–26.

- ↑ Boker A, Singer JP, Metchnikoff C, et al. High Dose Exposure to Voriconazole is Associated with Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma in Lung Transplant Recipients. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2011 In submission.

- ↑ Alam M, Brown RN, Silber DH, et al. Increased incidence and mortality associated with skin cancers after cardiac transplant. Am J Transplant. 2011;11(7):1488–1497.

- ↑ Brewer JD, Colegio OR, Phillips PK, et al. Incidence of and risk factors for skin cancer after heart transplant. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145(12):1391–1396

- ↑ Penn I. Post-transplant malignancy: the role of immunosuppression. Drug Saf. 2000;23(2):101–113.

- ↑ Stewart WB, Nicholson D, Hamilton G, et al. Eyelid tumors and renal transplantation. Arch Ophthalmol 1980;98:1771–2.

- ↑ Rowe DE, Carroll RJ, Day CL., Jr Prognostic factors for local recurrence, metastasis, and survival rates in squamous cell

- ↑ Rubben, A., Baron, J., & GrussendorfConen, E. (1996). Prevalence of human papillomavirus type 16-related DNA in cutaneous Bowen's disease and squamous cell cancer. International Journal of Oncology, 9, 609-611. https://doi.org/10.3892/ijo.9.4.609

- ↑ Leibovitch I, Huilgol SC, James CL, Hsuan JD, Davis G, Selva D. Periocular keratoacanthoma: Can we always rely on the clinical diagnosis? Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89:1201–4.

- ↑ Pe’er J. Pathology of eyelid tumors. Indian Journal of Ophthalmology. 2016;64(3):177-190. doi:10.4103/0301-4738.181752.

- ↑ Hoeijmakers JH. Genome maintenance mechanisms for preventing cancer. Nature. 2001;411(6835):366–374.

- ↑ Ratushny, V., Gober, M. D., Hick, R., Ridky, T. W., & Seykora, J. T. (2012). From keratinocyte to cancer: the pathogenesis and modeling of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 122(2), 464–472. http://doi.org/10.1172/JCI57415

- ↑ American Joint Committee on Cancer. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and other cutaneous carcinomas. In: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th ed. New York, NY: Springer; 2010:301-314.

- ↑ Calista, D., Riccioni, L., & Coccia, L. (2002). Successful treatment of squamous cell carcinoma of the lower eyelid with intralesional cidofovir. The British Journal of Ophthalmology, 86(8), 932–933.

- ↑ Mehta, Viraj J. MD, MBA; Ling, Jeanie MD; Sobel, Rachel K. MD. Review of Targeted Therapies for Periocular Tumors. International Ophthalmology Clinics: Winter 2017 - Volume 57 - Issue 1 - p 153–168 doi: 10.1097/IIO.0000000000000149

- ↑ Shields CL, Naseripour M, Shields JA,Eagle RC Jr. Topical mitomycin-C for pagetoid invasion of the conjunctiva by eyelid sebaceous gland carcinoma. Ophthalmology. 2002;109(11):2129–33.

- ↑ Lisman RD, Jakobiec FA, Small P. Sebaceous carcinoma of the eyelids. The role of adjunctive cryotherapy in the management of conjunctival pagetoid spread. Ophthalmology. 1989;96(7):1021–26.

- ↑ Rischin D, Khushalani NI, Schmults CD, Guminski A, Chang ALS, Lewis KD, Lim AM, Hernandez-Aya L, Hughes BGM, Schadendorf D, Hauschild A, Thai AA, Stankevich E, Booth J, Yoo SY, Li S, Chen Z, Okoye E, Chen CI, Mastey V, Sasane M, Lowy I, Fury MG, Migden MR. Integrated analysis of a phase 2 study of cemiplimab in advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: extended follow-up of outcomes and quality of life analysis. J Immunother Cancer. 2021 Aug;9(8):e002757. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2021-002757. PMID: 34413166.

- ↑ Balasubramanian A, Kannan NS. Eyelid Malignancies- Always Quite Challenging. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research : JCDR. 2017;11(3):XR01-XR04. doi:10.7860/JCDR/2017/23695.9582.