Seborrheic Keratosis

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Seborrheic keratosis (SK) is one of the most common skin tumors that is predominantly seen in adults. SK lesions are papules and/or plaques that have a predilection for the eyelid, forehead, and trunk; however, they can occur anywhere on the body with sparing of the palms and soles. Commonly, these lesions are beige, brown, or black and usually measure 3 to 20 mm in diameter. They often have a velvet or wart-like surface and appear to be "stuck on" the skin. [1] The presence of SK on a mucosal surface other than the conjunctiva has not been reported. [2] In rare cases, SK has been noted in the external ear canal or on the conjunctiva of the eye. [3][4] Eruptive SKs, known as the sign of Leser-Trelat, can represent a paraneoplastic condition that warrants urgent screening for underlying malignancy. Given the high prevalence and variable clinical appearance of SK, it is important for providers to be familiar with its diagnosis and management.

Seborrheic keratosis is recognized by the following codes as per the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) nomenclature:

ICD-9

702.1

ICD-10

L82.1

Epidemiology

Seborrheic keratosis is one of the most common benign epidermal skin tumors and affects over 80 million Americans.[5] There is no known gender predilection for SK. The increased prevalence of SK with increasing age is well known, particularly in those over 50 years of age, in which 80-100% of SK is detected.[6][7] A recent study found an average of 69 SK lesions per person in individuals over the age of 75.[8] SK appears to occur more frequently in individuals with lighter skin tones, especially in patients with a Fitzpatrick skin type 3 or less.[9]

Etiology

Seborrheic keratosis is a benign proliferation of immature keratinocytes between the basal layer and the keratinizing surface of the epidermis.[10] SK are typically slow growing and form well-demarcated, round or oval macules or papules. [11] Genetics, ultraviolet exposure, HPV p16, abnormal lipid and glucose metabolism are found to be associated with SK. These lesions are commonly considered a sign of skin aging due to chronic ultraviolet (UV) exposure. A viral hypothesis implicating HPV has been suggested, however was not proven by recent studies.[12]

Pathophysiology

The pathogenesis of seborrheic keratosis (SK) remains poorly understood. Immature epidermal keratinocytes slowly proliferate leading to macules, papules, and plaques known as seborrheic keratoses. [13] Recent studies have proposed that increased expression of the transmembrane protein – amyloid precursor protein (APP) – may play an important role. APP is mainly expressed in keratinocytes and melanocytes in the epidermal basal layer with only a small amount in the dermal fibroblasts of the epidermal-dermal junction.[14][15][16] The expression of APP is higher in UV-exposed skin and increases with age. APP was found to be present throughout all layers of SK tissue samples, and more extensively expressed when compared to adjacent normal skin tissue. [17][18] In epidermal keratinocytes, APP participates in protecting cells by inducing proliferation and migration while inhibiting apoptosis. [14][15][16][19][20]

APP is also believed to have a critical role in the regulation of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). Different types of mutations and up-regulation of EGFR have been implicated in SK in addition to other tumors. [17] Fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3, a tyrosine kinase) and /or PIK3CA oncogenes may also play a role in the development of SK. Activating mutations in the fibroblast growth factor receptor-3 (FGFR3), a tyrosine kinase receptor, are thought to drive the proliferation of epidermal keratinocytes.[18] [9] [21] There is a genetic disposition for the development of these lesions, however the exact inheritance pattern is not clear.

Pathology shows proliferation of keratinocytes with keratin-filled cysts. Hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, pseudocysts, hyperpigmentation, dyskeratosis, and lymphocytic infiltration (if inflamed) may also be seen. These lesions do not usually self resolve. [9]

Types of Seborrheic Keratosis:

- Acanthotic

- Hyperkeratotic

- Clonal

- Adenoid

- Irritated

- Melanoacanthoma

All of these subtypes of seborrheic keratosis have three features in common: hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and papillomatosis. The most common variant is acanthotic.

Two new rare variants have recently been described: adamantinoid seborrheic keratosis and seborrheic keratosis with pseudorosettes. Adamantinoid seborrheic keratosis is characterized by intercellular deposits of mucin, resembling adamantinoma where as seborrheic keratoses with pseudorosettes exhibit a peculiar distribution of basaloid neoplastic cells arranged radially around small central spaces resembling Flexner-Wintersteiner rosettes.[22]

Diagnosis

History

Seborrheic keratoses have a dull, waxy, verrucous, “stuck on” appearance. The lesions can be light brown, dark brown, yellow, or gray. There may be few or numerous lesions, and they can be anywhere on the body aside from the palms, soles, and most mucus membranes.[11] Patients may note slow growth of these lesions, pain, pruritus, erythema, bleeding, or may have no symptoms at all. If many of these lesions appear at once, it may be a sign of gastrointestinal or pulmonary malignancy; this is known as the sign of Leser-Trelat. [23]

Risk Factors

- Older age

- Genetics [24]

- Ultraviolet (UV) exposure

- Lower Fitzpatrick skin type

- HPV p16

- Abnormal lipid metabolism

- Abnormal glucose metabolism[17]

Physical Examination

Non-Ocular Seborrheic Keratosis

On non-ocular surfaces, SK typically presents as well-demarcated, uniform, brownish, slow-growing plaques with a verrucous surface giving its characteristic dull, waxy, greasy, "stuck on” appearance. [11] Often further workup is not needed. While these lesions are benign, thorough physical examination is recommended to assess for co-existing melanoma or basal cell carcinoma. A multidisciplinary approach involving dermatology can aid in a detailed physical exam. If concerning features are present, such as ulcerated lesions or rapidly changing lesions, a dermatoscope and skin biopsy allow for further classification. Dermoscopy shows milia cysts, comedo-like openings, fissures, and ridges. For example, if found in the genital area, SK can easily be misinterpreted as human papillomavirus (HPV) lesions or extramammary Paget's disease. [18][25]

Ocular and Peri-Ocular Seborrheic Keratosis

Seborrheic keratosis on the eyelid is more commonly seen than conjunctival lesions. These typically present with the same classic “stuck on,” coin-shaped, brown lesions. Due to the thinner skin of the eyelid, these lesions may appear wrinkled as compared to thicker areas of the body including the brow and forehead area.

Conjunctival Seborrheic Keratosis

Seborrheic keratosis is most commonly found on the skin; however, recent studies describe a handful of cases of conjunctival lesions diagnosed as seborrheic keratosis by histopathological analysis. Conjunctival SK lesions typically present as a gelatinous, grey-white nodule with or without pigmentation, on the surface of the eye. This is thought to be due to the moist environment on the conjunctiva compared to the dry environment of skin. [26] Most of the conjunctival growths in the literature were initially diagnosed as malignant melanomas as they were rapidly growing pigmented conjunctival lesions. Clinically, one case was described as a recurrent, slow growing, juxta-limbal, lobulated, pink mass that was elevated and extending onto the cornea. Once the tumor was excised for the second time, pathology reports showed an irregular epithelial proliferation with papillomatous changes and keratin containing pseudo-horn cysts. Areas of epithelial atypia with descending epithelial nests without cellular malformations, nuclear pleomorphisms, or dysplastic changes may also be seen. In cases of conjunctival lesions, histopathology is crucial in differentiating a malignant melanoma from a benign, and exceedingly rare, conjunctival seborrheic keratosis. [27]

Sign of Leser-Trelat

Rapid formation of many SKs can represent a paraneoplastic condition associated with an underlying malignancy, known as the sign of Leser-Trelat. An association with gastrointestinal, pulmonary, and other internal malignancies have been described. [9] Screening for underlying malignancy is crucial in this setting. [23] A Pseudo-Leser-Trelat sign has also been described in association with chemotherapy with drugs such as cytarabine, docetaxal, gemcitabine, or PD1 inhibitors.[18] The Pseudo-Leser-Trelat sign has also been reported in inflammatory dermatitis such as eczema. [28]

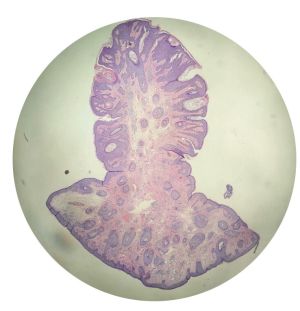

Histology

A diagnosis of seborrheic keratosis is often confirmed with histology in addition to associated findings such as age, skin pigmentation, and quantity and quality of lesions. [2] There is great variability in the clinical and histologic appearance of SK.[21]

Types of Seborrheic Keratosis:

- Acanthotic

- Hyperkeratotic

- Clonal

- Adenoid/Reticular

- Irritated

- Melanoacanthoma

Pathology shows proliferation of keratinocytes with keratin-filled cysts. Horn cysts (foci of abrupt complete keratinization with a thin layer of surrounding granular cell layer) may be seen. Hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, pseudocysts, hyperpigmentation, dyskeratosis, papillomatosis, and lymphocytes (if inflamed) are also common findings. All of the above subtypes of seborrheic keratosis have three features in common: hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and papillomatosis. The most common variant is acanthotic. These lesions do not usually self resolve. [9]

Two new rare variants have recently been described: adamantinoid seborrheic keratosis and seborrheic keratosis with pseudorosettes. Adamantinoid seborrheic keratosis is characterized by intercellular deposits of mucin, resembling adamantinoma where as seborrheic keratoses with pseudorosettes exhibit a peculiar distribution of basaloid neoplastic cells arranged radially around small central spaces resembling Flexner-Wintersteiner rosettes.[22]

Differential Diagnosis

- Malignant melanoma

- Actinic keratosis

- Lentigo maligna

- Melanocytic nevus

- Squamous cell carcinoma

- Pigmented basal cell carcinoma [29]

- Verruca Vulgaris

- Condyloma Acuminata

- Hidroacanthoma Simplex

- Hypertrophic Actinic Keratosis

- Fibroepithelial Polyp

- Epidermal Nevus

Management

Seborrheic keratosis is a benign tumor and does not typically require treatment; however, the majority of patients seek therapeutic interventions electively for cosmetic changes or to improve associated symptoms such as ocular irritation. Photography can also be used to identify interval changes such as growth. If there are any abnormal features including ulceration, irregular or pearly borders, telangiectasias, growth, inflammation or destruction of nearby tissues, a biopsy should be performed to exclude malignancy. Therapeutic interventions utilized for SK are cryotherapy, shave-type excision, electrodessication with or without curettage, topical agents, and laser therapy.[9]

Cryotherapy

Cryotherapy is a common treatment utilized for seborrheic keratosis and is generally well tolerated.[30] In cryotherapy, liquid nitrogen or CO2 is used to freeze/thaw targeted cells leading to cell death. The number of cycles needed to freeze/thaw the targeted cells depends on the thickness of the lesion. This treatment modality does not allow for histological confirmation and should only be performed on lesions with low clinical suspicion for malignancy. The location of the lesion should also be considered as cryotherapy in the periocular area can lead to eyelid notching or contour irregularities or cicatricial ectropion. Other complications reported from cryotherapy include erythema, pain, bulla formation and some reports of post-procedure hypopigmentation or hyperpigmentation.[9]

Shave Excision

One of the most common treatment modalities for removal for seborrheic keratosis is a shave-type excision at the epidermal-dermal junction, leaving the deep layers of the skin intact. Shave excision requires local anesthesia and is performed with a scalpel, special exfoliating blade, or double-edged razor blade. [9]

Electrodessication

Electrodessication with or without curettage can be used for skin conditions that are found in the epidermis without dermis involvement. This procedure is performed in an outpatient setting with local anesthesia and uses a curette to remove epidermal tissue followed by electrodessication with a hyfrecator or cautery unit. While electrodessication has low rates of complications, risks include infection, scarring and hyperpigmentation.[9]

Topical Agents

Studies on the use of topical agents for treatment of seborrheic keratoses are limited. Studies on agents such as tazarotene, imiquimod cream, alpha hydroxy acids, urea ointment, tacalcitol and calcipotriol have shown promising results. [9] Recently, topical hydrogen peroxide solution was FDA approved for the treatment of seborrheic keratosis. [31][32] A higher mean per patient percentage of seborrheic keratoses were found to be clear or nearly clear with topical 40% hydrogen peroxide topical solution when compared with vehicle. [33]The use of hydrogen peroxide is generally well tolerated however side effects include erythema, scaling and hyperpigmentation.

Laser Therapy

Two types of laser techniques exist for the treatment of seborrheic keratosis: ablative and non-ablative laser therapy. Ablative laser therapy consists of Er:YAG (erbium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet) and CO2 lasers, while the non-ablative laser is a 755nm alexandrite laser. Er:YAG has demonstrated less hyperpigmentation than cryotherapy for SK. Although laser therapy has been shown to be efficacious, it is more expensive than the other treatment options and its benefit of use over other therapeutic methods has not been established. [18]Ablative therapies such as Er:YAG (erbium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet) laser show a lower recurrence rate when compared with shaving.[34][35] Additionally, Er:YAG has been shown to have significantly lower rates of hyper-pigmentary changes when compared with cryotherapy.[36]

Ophthalmic Implications in Treatment

Conjunctival Seborrheic Keratosis

The management of SK on the conjunctiva is limited by its rarity. To date there have only been five cases of conjunctival SK. [2][37][38] [39]Since SK can mimic conjunctival melanoma, all five cases were treated with wide local excision and adjuvant topical therapies intra and post-operatively. This is recommended given the aggressive nature of conjunctival melanoma which is common in the differential of this conjunctival lesion.[2]

Seborrheic Keratosis of the Eyelid

Seborrheic keratosis of the eyelid has a classic presentation and is therefore simpler to diagnose and treat. Surgical excision is the treatment of choice for most ophthalmologists. However, cryotherapy, electrodessication, and laser therapy can also be implemented.

Complications

Seborrheic keratoses are common slow growing lesions that can thicken over time. Physical irritation can occur based on their location and can include ocular surface irritation, mechanical ptosis, and catching on clothing. SK can closely resemble precancerous lesions, most commonly actinic keratosis. They can also become inflamed and resemble basal cell carcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma. Basal cell carcinoma arising from SK has also been reported.[40] Biopsy should be performed in any cases of diagnostic uncertainty. When there are numerous SK lesions, detection of other malignant skin lesions can become more challenging and require a high degree of suspicion.[11] Seborrheic keratosis on the conjunctiva is typically benign, however, recurrence of the lesion suggests malignancy until proven otherwise. These patients also require close follow-up. [26]

Prognosis

The prognosis of seborrheic keratosis is excellent. Recurrence rates of previously treated SK of the skin is not well defined. However, if the lesion continues to recur, a biopsy should be performed to assess for malignancy. Outcomes of conjunctival SK are limited but the two confirmed conjunctival SK lesions reported in Tseng et. al. did not have any recurrence. In contrast, Vassiliki et. al,, demonstrated recurrence of SK. [26][2] Sudden eruption of multiple seborrheic keratoses, known as the sign of Leser-Trelat can be a poor prognostic sign due to its association with internal malignancy. [41]

Summary

Seborrheic keratosis is one of the most common benign skin lesions and frequently occurs on the eyelids. While the occurrence of SK on the conjunctiva is rare, it can be considered in the differential diagnosis with patients presenting with conjunctival lesions.[4] Being familiar with the presentation of seborrheic keratosis on different areas of the body is necessary not only for ophthalmologists, but also for all clinicians, as misdiagnosis can lead to delayed diagnosis of the underlying malignant tumors.

References

- ↑ Choi JW, Park YW, Byun SY, Youn SW. Differentiation of Benign Pigmented Skin Lesions with the Aid of Computer Image Analysis: A Novel Approach. Ann Dermatol. 2013;25(3):340. doi:10.5021/AD.2013.25.3.340

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Tseng SH, Chen YT, Huang FC, Jin YT. Seborrheic keratosis of conjunctiva simulating a malignant melanoma: an immunocytochemical study with impression cytology. Ophthalmology. 1999 Aug;106(8):1516-20. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90446-3. PMID: 10442897.

- ↑ de Loof M, van Dorpe J, van der Meulen J, et al. : Two cases of seborrheic keratosis of the external ear canal: Involvement of PIK3CA and FGFR3 genes. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57(6):703–6. 10.1111/ijd.13943

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Kim JH, Bae HW, Lee KK, Kim TI, Kim EK. Seborrheic keratosis of the conjunctiva: a case report. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2009;23(4):306-308. doi:10.3341/kjo.2009.23.4.306

- ↑ Braun RP, Ludwig S, Marghoob AA. Differential Diagnosis of Seborrheic Keratosis: Clinical and Dermoscopic Features. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017 Sep 01;16(9):835-842

- ↑ Kwon OS, Hwang EJ, Bae JH, et al Seborrheic keratosis in the Korean males: causative role of sunlight. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed 2003;19:

- ↑ Yeatman JM, Kilkenny M, Marks R. The prevalence of seborrhoeic keratoses in an Australian population: does exposure to sunlight play a part in their frequency? Br J Dermatol 1997;137:411–414

- ↑ Hafner C, Hartmann A, van Oers JMM, et al. FGFR3 mutations in seborrheic keratoses are already present in flat lesions and associated with age and localization. Modern pathology : an official journal of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology, Inc. 2007;20(8):895-903. doi:10.1038/modpathol.3800837

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 9.8 9.9 Greco MJ, Bhutta BS. Seborrheic Keratosis. [Updated 2021 Aug 11]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545285/

- ↑ Tsambaos D, Monastirli A, Kapranos N, et al. Detection of human papillomavirus DNA in nongenital seborrheic keratoses. Arch Dermatol Res. 1995;287:612–615.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Greco MJ, Bhutta BS. Seborrheic Keratosis. [Updated 2021 Aug 11]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545285/

- ↑ Kambiz KH, Kaveh D, Maede D, Hossein A, Nessa A, Ziba R, Alireza G. Human Papillomavirus Deoxyribonucleic Acid may not be Detected in Non-genital Benign

- ↑ Minagawa A. Dermoscopy–pathology relationship in seborrheic keratosis. J Dermatol. 2017;44(5):518-524. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.13657

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Herzog V, Kirfel G, Siemes C, Schmitz A. Biological roles of APP in the epidermis. Eur J Cell Biol 2004; 83: 613–624.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Botelho MG, Wang X, Arndt-Jovin DJ, Becker D, Jovin TM. Induction of terminal differentiation in melanoma cells on downregulation of beta-amyloid precursor protein. J Invest Dermatol 2010; 130: 1400–1410

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Hoffmann J, Twiesselmann C, Kummer MP, Romagnoli P, Herzog V. A possible role for the Alzheimer amyloid precursor protein in the regulation of epidermal basal cell proliferation. Eur J Cell Biol 2000; 79: 905–914.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Li Y, Wang Y, Zhang W, et al. Overexpression of amyloid precursor protein promotes the onset of seborrhoeic keratosis and is related to skin ageing. Acta Dermato-Venereologica. 98(6):594-600. doi:10.2340/00015555-2911

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 Wollina U, Chokoeva A, Tchernev G, et al. : Anogenital giant seborrheic keratosis. G Ital Dermatol Venereol.2017;152(4):383–6. 10.23736/S0392-0488.16.04945-2

- ↑ Siemes C, Quast T, Kummer C, Wehner S, Kirfel G, Muller U, et al. Keratinocytes from APP/APLP2-deficient mice are impaired in proliferation, adhesion and migration in vitro. Exp Cell Res 2006; 312: 1939–1949.

- ↑ Kirfel G, Borm B, Rigort A, Herzog V. The secretory betaamyloid precursor protein is a motogen for human epidermal keratinocytes. Eur J Cell Biol 2002; 81: 664–676.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Jackson JM, Alexis A, Berman B, Berson D, Taylor S, Weiss J. Current Understanding of Seborrheic Keratosis: Prevalence, Etiology, Clinical Presentation, Diagnosis, and Management. J Drugs Dermatology. 2015;14(10). https://jddonline.com/articles/dermatology/S1545961615P1119X.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Requena L, Kutzner H. Seborrheic keratosis with pseudorosettes and adamantinoid seborrheic keratosis: two new histopathologic variants. J Cutan Pathol. 2006 Sep;33 Suppl 2:42-5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2006.00528.x. PMID: 16972954.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Narala A, Cohen S, Narala S, Cohen PR, Author C. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma-associated Leser-Trélat sign: Report and world literature review. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23(1):4-5. doi:10.5070/D3231033672

- ↑ Rongioletti F, Corbella L, Rebora A. Multiple familial seborrheic keratoses. Dermatologica 1988;176:43–45.

- ↑ Sudhakar N, Venkatesan S, Mohanasundari PS, et al. : Seborrheic keratosis over genitalia masquerading as Buschke Lowenstein tumor. Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS. 2015;36(1):77–9. 10.4103/0253-

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Vassiliki Tsakalaki, Aikaterini Halkia, Viktor Haniotis, Maria Kafousi, Efstathios T. Detorakis Conjunctival Seborrheic Keratosis Manifesting as Squamous Carcinoma, Ophthalmology, Volume 120, Issue 2, 2013, Pages 428-428.e1, ISSN 0161-6420, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.09.026.

- ↑ Kim JH, Bae HW, Lee KK, Kim TI, Kim EK. Seborrheic keratosis of the conjunctiva: a case report. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2009;23(4):306-308. doi:10.3341/kjo.2009.23.4.306.

- ↑ Greco M, Bhutta B. Seborrheic Keratosis. Dermatological Cryosurgery and Cryotherapy. August 2021:589-593. doi:10.1007/978-1-4471-6765-5_113

- ↑ Brandão ML, Lima CMO, Moura HH, et al. Dermatoscopic findings of seborrheic keratosis in melanoma. Acta Dermatovenerologica Croat. 2016;24(2):144-147. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27477176/.

- ↑ Ranasinghe GC, Friedman AJ. Managing Seborrheic Keratoses: Evolving Strategies for Optimizing Patient Outcomes. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017 Nov 01;16(11):1064-1068.

- ↑ DuBois JC, Jarratt M, Beger BB, Bradshaw M, Powala CV, Shanler SD. A-101, a Proprietary Topical Formulation of High-Concentration Hydrogen Peroxide Solution: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Vehicle-Controlled, Parallel Group Study of the Dose-Response Profile in Subjects With Seborrheic Keratosis of the Face. Dermatol Surg. 2018 Mar;44(3):330-340.

- ↑ Kao S, Kiss A, Efimova T, Friedman AJ. Managing Seborrheic Keratosis: Evolving Strategies and Optimal Therapeutic Outcomes. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018 Sep 01;17(9):933-940.

- ↑ Baumann LS, Blauvelt A, Draelos ZD, Kempers SE, Lupo MP, Schlessinger J, Smith SR, Wilson DC, Bradshaw M, Estes E, Shanler SD. Safety and efficacy of hydrogen peroxide topical solution, 40% (w/w), in patients with seborrheic keratoses: Results from 2 identical, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 studies (A-101-SEBK-301/302). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 Nov;79(5):869-877. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.05.044. Epub 2018 Jun 1. Erratum in: J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021 Aug;85(2):531. PMID: 29864467.

- ↑ Wollina U: Erbium-YAG laser therapy – analysis of more than 1,200 treatments. Glob Dermatol. 2016; 3(2): 268–72.

- ↑ Sayan A, Sindel A, Ethunandan M, et al.: Management of seborrhoeic keratosis and actinic keratosis with an erbium:YAG laser-experience with 547 patients. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2019; 48(7): 902–7.

- ↑ Gurel MS, Aral BB: Effectiveness of erbium:YAG laser and cryosurgery in seborrheic keratoses: Randomized, prospective intraindividual comparison study. J Dermatolog Treat. 2015; 26(5): 477–80.

- ↑ Jain AK, Sukhija J, Radotra B, Malhotra V. Seborrheic keratosis of the conjunctiva. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2004 Jun;52(2):154-5. PMID: 15283223.

- ↑ Kim JH, Bae HW, Lee KK, Kim TI, Kim EK. Seborrheic keratosis of the conjunctiva: a case report. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2009;23(4):306-308. doi:10.3341/kjo.2009.23.4.306

- ↑ Gulias-Cañizo R, Aranda-Rábago J, Rodríguez-Reyes AA. Queratosis seborreica de la conjuntiva: informe de un caso [Seborrheic keratosis of conjunctiva: a case report]. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol. 2006 Apr;81(4):217-9. Spanish. doi: 10.4321/s0365-66912006000400008. PMID: 16688646.

- ↑ Bedir R, Yurdakul C, Güçer H, Sehitoglu I. Basal Cell Carcinoma Arising within Seborrheic Keratosis. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8(7):YD06-YD7. doi:10.7860/JCDR/2014/8665.460

- ↑ Bernett CN, Schmieder GJ. Leser Trelat Sign. [Updated 2020 Sep 3]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470554/