Madarosis

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

In ophthalmology, the term madarosis generally refers to the loss of eyelashes.

Disease

Madarosis is a clinical sign that refers to eyelash or eyebrow loss from any cause.[1] The word originates from the Greek word “madao” which means to fall off. Similarly, milphosis refers to eyelash loss or the falling out of eyelashes. The two terms are often used synonymously.[1][2] Other terms related to eyelash loss include alopecia adnata (underdevelopment of the eyelashes), trichotillomania (hair/eyelash loss due to compulsive pulling/avulsion of hairs), and alopecia (broad term that describes the absence or loss of hair from any skin region where it is normally present).[3] [4]

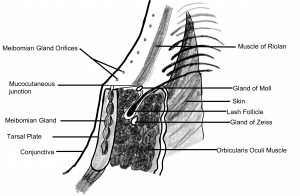

Anatomy

Eyelash hairs are short, thick, and curved in appearance. The lower eyelashes curve downwards while the upper eyelashes curve upwards.[5] Functionally, this prevents interlacing and protects the eyeball from foreign bodies and irritants.[6] Eyelash hairs typically develop in rows of 2-3 hairs, growing approximately 0.15 mm per day. Eyelash hairs can take up to 8-10 weeks to grow, and last for 5-6 months before falling out.[7]

Classification

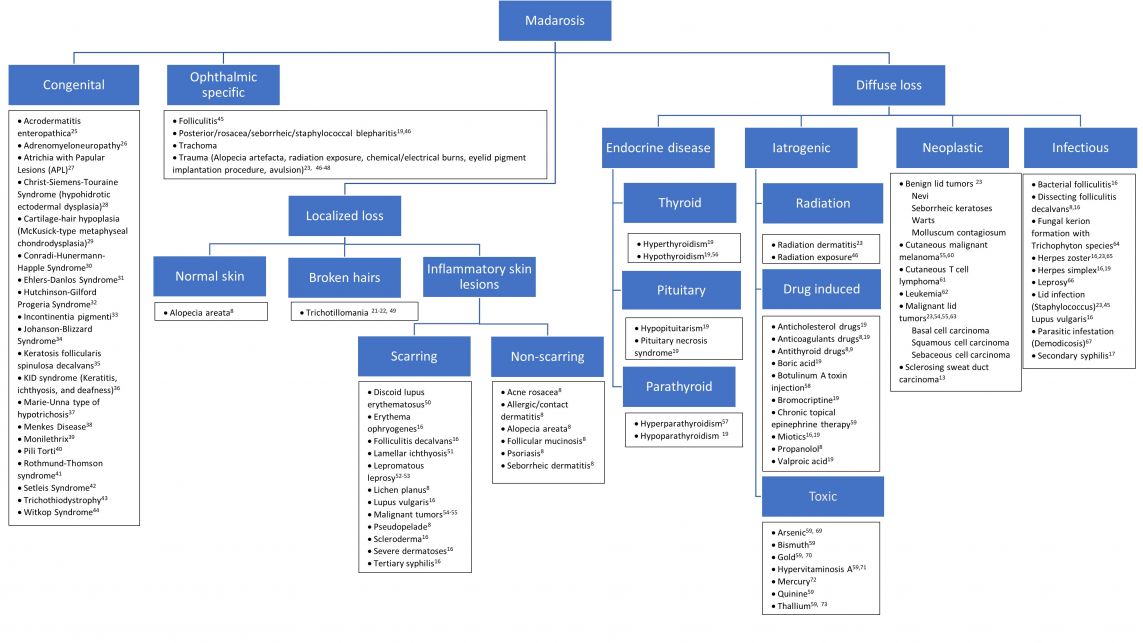

Madarosis is classified based on two pathogenic pathways: scarring and non-scarring processes of the hair follicle. This classification system is based on the potential for eyelash regrowth and is dependent on the severity of the pre-existing condition.[3] [4] [8]

Scarring madarosis: Refers to irreversible loss of eyelash hair due to destructive processes of the hair follicle.[3] [4] [8] Common causes include discoid lupus erythematosus, lichen planopilaris, and malignant tumors (squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma).[9] [10] [11] [12] [13] Deep inflammatory processes such as folliculitis decalvans, tertiary syphilis, and lupus vulgaris can also cause scarring madarosis.[14] [15] [16]

Non-scarring madarosis: Refers to reversible loss of eyelash hair due to non-destructive processes of the hair follicle.[3] [4] [8] Common causes include superficial inflammatory processes such as psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, secondary syphilis, and seborrheic dermatitis, as well as entities that alter cell cycle kinetics such as thyroid hormonal disturbances.[8][17] [18] [19]

Diagnosis

History

The majority of madarosis will be due to localized eyelid conditions like blepharitis, dermatologic disease or localized neoplasia.

When the diagnosis is not immediately clear on exam, it will be important to keep a broad differential. Obtain a complete medical history. Specifically ask about dermatologic, endocrine, neoplastic, autoimmune and infectious disease. Trauma, nutritional deficiency, medications and allergens can also be causative. A family history is important in congenital cases.[3] [4][20] In the right clinical context, a psychosocial history may be supportive of a diagnosis of trichotillomania.[21] [22]

Ask about hair loss in other body regions. Concurrent hair loss can suggest dermatological, endocrine, autoimmune, congenital, or drug-induced causes.[3] [4] [20]

Physical Examination

Madarosis is a clinical diagnosis.

On a local inspection, identify:

- The extent of lash loss (localized, or diffuse)

- The presence of eye lash or eyebrow hair regrowing at different rates, or having broken ends (suggestive of a diagnosis of trichotillomania)[21] [22]

- Blepharitis[23]

- Lesions along the eyelash margin[24]

- Localized skin rash[20]

- Associated loss of eyebrow hairs

On a systemic exam, identify:

- Stigmata of skin disease[20]

- Associated hair loss

Diagnostic procedures

Ophthalmic causes should be referred to an ophthalmologist. Non-ophthalmic causes should be referred to a dermatologist or family physician.

Differential diagnosis

Refer to figure 2 for approach to the differential diagnosis.

Management

Treatment of madarosis is dependent upon treatment of the predisposing disorder. Identification of the underlying disorder is critical for the management of madarosis.

General treatment

Non-scarring madarosis:

- Correction of underlying primary disorder often results in regrowth of eyelash/eyebrow hair

- Exception: Lepromatous leprosy, although a non-scarring process, generally does not result in hair regrowth after treatment of disorder[25][26]

Scarring madarosis:

- Correction of underlying primary disorder does not result in regrowth of eyelash/eyebrow hair

- Hair transplant, eyelash/eyebrow reconstruction, and cosmesis are viable options for disorders causing hair follicle destruction such as inflammatory dermatoses, infection, trauma, malignancy, and congenital causes[3] [4]

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 Sachdeva S, Prasher P. Madarosis: A dermatological marker. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74(1):74–6.

- ↑ Barlow-Pugh M. Stedmans Medical Dictionary, 27th Edition. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000.

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 Khong JJ, Casson RJ, Huilgol SC, Selva D. Madarosis. Surv Ophthalmol. 2006;51(6):550-60.

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 Kumar A, Karthikeyan K. Madarosis: A marker of many maladies. Int J Trichology. 2012;4(1):3-18.

- ↑ Dawber RP, Messenger AG. Hair follicle structure, keratinization and the physical properties of hair. In: Dawber R, editor. Diseases of the hair and scalp. 3rd ed. London: Blackwell Scientific; 1997. p. 44.

- ↑ Robbins CR, editor. Chemical and physical behavior of human hair. 4th ed. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2002. p. 8.

- ↑ Vickery SA, Wyatt P, Gilley J. Eye cosmetics. In: Draelos ZD, editor. In: Cosmetic Dermatology:Products and Procedures. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley Blackwell; 2010. p. 191.

- ↑ Jump up to: 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Maguire HC, Hanno R: Diseases of the hair, in Moschella SL, Hurley HJ (eds): Dermatology. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, ed 2 1985, p. 1369—86.

- ↑ Ricotti C, Tozman E, Fernandez A, Nousari CH. Unilateral eyelid discoid lupus erythematosus. AmJ Dermatopathol. 2008;30:512–3.

- ↑ Kossard S, Lee MS, Wilkinson B. Postmenopausal frontal fibrosing alopecia: A frontal variant oflichen planopilaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:59–66.

- ↑ Hinds G, Thomas VD. Malignancy and Cancer Treatment-Related Hair and Nail Changes.Dermatol Clin. 2008;26:59–68.

- ↑ Jakobiec FA, Zakka FR, Hatton MP. Eyelid basal cell carcinoma developing in an epidermoidcyst: A previously unreported event. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;26:491–4.

- ↑ Kodama T, Tane N, Ohira A, Maruyama R, Fukuyama J. Sclerosing sweat duct carcinoma of the eyelid. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2004;48:7–11.

- ↑ Emmerson RW. Follicular mucinosis. A study of 47 patients. Br J Dermatol. 1969;81:395–413.

- ↑ Oztaş P, Catal F, Dilmen U. Familial eyebrow diffuse alopecia. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol.2005;19:118–9.

- ↑ Orentreich DS, Orentreich N: Dermatology of the eyelids, in Smith BC, Della Rocca RC, Nesi F (eds): Ophthalmic Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. St. Louis, CV Mosby, 1987, p. 855-906.

- ↑ Ploeg De, Stagnone JJ. Eyebrow alopecia in secondary syphilis. Arch Dermatol. 1964;90:172–3.

- ↑ Rook A. Endocrine influences on hair growth. Br Med J. 1965;1:609-14.

- ↑ Jordan DR, Ahuja N, Khouri L. Eyelash loss associated with hyperthyroidism. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;18(3):219-22.

- ↑ Jump up to: 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 Vij A, Bergfeld WF. Madarosis, milphosis, eyelash trichomegaly, and dermatochalasis. Clins in Derm. 2015;33:217-26.

- ↑ Jump up to: 21.0 21.1 Mawn LA, Jordan DR: Trichotillomania. Ophthalmology. 1997;104:2175-80

- ↑ Jump up to: 22.0 22.1 Smith JR: Trichotillomania: ophthalmic presentation. Aust NZ J Ophthalmol. 1995;23:59-61

- ↑ Giovinazzo VJ, Rodrı´guez-Sains RS: Ophthalmologic oncology: alopecia of the eyelashes. J Dermatol Surg Oncol 1984;10:182-85

- ↑ Cruz AA, Zenha F, Silva JT, et al: Eyelid involvement in paracoccidioidomycosis. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;20:212-16

- ↑ Kingery FA: Eyebrows, plus or minus. JAMA. 1966;195:571

- ↑ Mvogo CE, Bella-Hiag AL, Ellong A, Achu JH, Nkeng PF. Ocular complications of leprosy in Cameroon. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2001;79:31–3.

- Neldner KH, Hambidge KM, Walravens PA. Acrodermatitis enteropathica. Int J Dermatol.1978;17:380–87.

- König A, Happle R, Tchitcherina E, Schaefer JR, Sokolowski P, Köhler W, et al. An X- linkedgene involved in androgenetic alopecia: a lesson to be learned from adrenoleukodystrophy. Dermatology. 2000;200:213–18.

- Zlotogorski A, Panteleyev AA, Aite VM, Christiano AM. Clinical and molecular diagnostic criteria congenital atrichia papular lesions. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;118:887–90.

- Rajagopalan K, Tay CH. Hidrotic ectodermal dysplasia: study of a large Chinese pedigree. ArchDermatol. 1977;113:481–85.

- Mäkitie O, Sulisalo T, de la Chapelle A, Kaitila I. Cartilage-hair hypoplasia. J Med Genet.1995;32:39-43

- Hartman RD, Molho-Pessach V, Schaffer JV. Conradi-Hünermann-Happle syndrome. DermatolOnline J. 2010;16:4.

- Faiyaz-Ul-Haque M, Zaidi SH, Al-Ali M, Al-Mureikhi MS, Kennedy S, Al-Thani G, et al. A novel missense mutation in the galactosyltransferase-I (B4GALT7) gene in a family exhibiting facioskeletal anomalies and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome resembling the progeroid type. Am J Med Genet. 2004;128A:39–45.

- Agarwal US, Sitaraman S, Mehta S, Panse G. Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76(5):591-593

- Arenas-Sordo ML, Vallejo-Vega B, Hernandez-Zamora E, Galvez-Rosas A, Montoya-Perez LA. Incontinentia pigmenti (IP2): familiar case report with affected men. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2005;10:122-129.

- Alpay F, Gül D, Lenk MK, Oğur G. Severe intrauterine growth retardation, aged facial appearance, and congenital heart disease in a newborn with Johanson-Blizzard syndrome. Pediatr Cardiol. 2000;21:389–90.

- Verma R, Bhatnagar A, Vasudevan B, Kumar S. Keratosis follicularis spinulosa decalvans. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016;82(2):1-2.

- Skinner BA, Greist MC, Norins AL. The keratitis, ichthyosis, and deafness (KID) syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1981;117:285–9.

- Celik HH, Surucu SH, Aldur MM, Ozdemir BM, Karaduman AA, Cumhur MM. Light and scanning electron microscopic examination of late changes in hair with hereditary trichodysplasia (Marie Unna hypotrichosis). Saudi Med J. 2004;25:1648–51.

- Bankier A. Menkes disease. J Med Genet. 1995;32:213–5.

- Tamayo L. Monilethrix treated with the oral retinoid Ro 10-9359 (Tigason) Clin Exp Dermatol. 1983;8:393–6.

- Gelles LN. Picture of the month. Pili torti. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153(6):647–48.

- Larizza L, Roversi R, Volpi L. Rothmund-Thomson syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2010;5:2.

- McGaughran J, Aftimos S. Setleis syndrome: Three new cases and a review of the literature. Am JMed Genet. 2002;111:376–80.

- Itin PH, Fistarol SK. Hair Shaft Abnormalities –Clues to Diagnosis and Treatment. Dermatology. 2005;211:63–71

- Chitty LS, Dennis N, Baraitser M. Hidrotic ectodermal dysplasia of hair, teeth, and nails: Case reports and review. J Med Genet. 1996;33:707–10.

- Wright P. The eye and skin. In: Verbov J, editor. Relationships in dermatology. London: Kluwers Academic Publishers; 1988. pp. 35–6.

- Zehetmayer M, Kitz K, Menapace R, et al: Local tumor control and morbidity after one to three fractions of stereotactic external beam irradiation for uveal melanoma. Radiother Oncol. 2000;55:135-44

- Tse DT, Folberg R, Moore K. Clinicopathologic correlate of a fresh eyelid pigment implantation. Arch Ophthalmol. 1985;103:1515-7

- Goldberg SH, Bullock JD, Connelly PJ. Eyelid avulsion: a clinical and experimental study. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;8:256-61

- Mehregan AH. Trichotillomania. A clinicopathologic study. Arch Dermatol. 1970;102:129-33

- Acharya N, Pineda R, Uy HS, Foster S. Discoid lupus erythematosus masquerading as chronic blepharoconjunctivitis. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:e19-23.

- Cruz AA, Menezes FA, Chaves R, Coelho RP, Velasco EF, Kikuta H. Eyelid abnormalities in lamellar ichthyoses. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:1895-98

- Dana MR, Hochman MA, Viana MA, Hill CH, Sugar J. Ocular manifestations of leprosy in a noninstitutionalized community in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 1994;112:626-29

- Doxanas MT, Green WR. Sebaceous gland carcinoma. Review of 40 cases. Arch Ophthalmol. 1984;102:245-49

- Piest KL. Malignant lesions of the eyelids. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1992;18:1056-59

- Saito R, Nishiyama S. Alopecia in hypothyroidism. Hair Research. 1981:355-356

- Alonso LC, Rosenfield RL. Molecular genetic and endocrine mechanisms of hair growth. HormRes. 2003;60:1–13

- Kowing D. Madarosis and facial alopecia presumed secondary to botulinum a toxin injections. Optom Vis Sci. 2005;82:579-82

- Kass MA, Stamper RL, Becker B. Madarosis in chronic epinephrine therapy. Arch Ophthalmol 1972;88:429-31

- Martel A, Oberic A, Moulin A, Zografos L, Hamedani M. Eyelids metastases from uveal melanoma: clinical and histopathologic features of two cases and literature review. Eye. 2019;33(5):767-771

- Leib ML, Lester H, Braunstein RE, Edelson RL. Ocular findings in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Ann Ophthalmol. 1991;23(5):182-86

- Wyatt AJ, Sachs DL, Shia J, Delgado R, Busam KJ. Virus-associated trichodysplasia spinulosa. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:241–6.

- Carter SR. Eyelid disorders: diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician. 1998;57(11):2695-702

- Basak SA, Berk DR, Lueder GT, Bayliss SJ. Common features of periocular tinea. ArchOphthalmol. 2011;129:306–9.

- Holz HA, Espandar L, Moshirfar M. Herpes Zoster Ophthalmicus (HZO) In: Yanoff M, Duker JS,editors. Ophthalmology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Mosby Elsevier; 2009. pp. 222–5.

- Cakiner T, Karacorlu MA. Ophthalmic findings of newly diagnosed leprosy patients in Istanbul Leprosy Hospital, Turkey. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 1998;76:100-102

- Gao YY, Di Pascuale MA, Li W, Liu DT, Baradaran-Rafii A, Elizondo A. High prevalence of Demodex in eye lashes with cylindrical dandruff. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:3094–8.

- Amster E, Tiwary A, Schenker MB. Case report: Potential arsenic toxicosis secondary to herbal kelp supplement. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115:606-608.

- Bandilla K, Gross D, Gross W. Oral gold therapy with auranofin (SK&F 39162). A multicenter open study in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol Suppl. 1982;8:154-159.

- Oliver TK, Havener WH. Eye manifestations of chronic vitamin A intoxication. AMA Arch Ophthalmol. 1958;60:19–22.

- Dawber RP, Simpson NB, Barth JH. Diffuse alopecia: Endocrine, metabolic and chemical influences in the follicular cycle. In: Dawber R, editor. Diseases of the hair and scalp. 3rd ed. London:Blackwell Scientific; 1997. p. 147

- Tromme I, Van Neste D, Dobbelaere F, Bouffioux B, Courtin C, Dugernier T, et al. Skin signs in the diagnosis of thallium poisoning. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:321–5.