Orbital Teratoma

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Orbital Teratoma

Disease Entity

Diagnosis Code from ICD-10 Version 2017 : D31.6 Short Description: Benign neoplasm of unspecified site of orbit applicable to

- Benign neoplasm of connective tissue of orbit.

- Benign neoplasm of extraocular muscle.

- Benign neoplasm of peripheral nerves of orbit.

- Benign neoplasm of retrobulbar tissue.

- Benign neoplasm of retro-ocular tissue.

Disease

Introduction

A teratoma is a unilateral, congenital neoplasm containing structures originating from all three germinal cell layers, and it exhibits a pattern of growth foreign to its anatomic site. The orbit is a rare, but typical, location in which primary extragonadal germ cell tumors arise.[1]

The origin of teratoma has been derived from Greek word “Teratos” and “Oma”. The literal meaning of which accounts to teratos meaning unusual occurrence or phenomenon, monster and oma meaning complete set of, or a condition.

Historical Reporting

Holmes first reported an orbital tumor compatible with a teratoma in 1863,[2] but due to the primitive histopathological methods available at that time, Broer and Weigert are credited with describing the first unquestionable orbital teratoma in 1876.[3] Seven years later, Lawson reported an orbital teratoma that extended into the intracranial cavity,[4] and in 1924 Prym briefly described an intracranial teratoma extending into the orbit.[5]

Etiopathogenesis

Teratomas, the most common of orbital germ cell tumors, probably arise from pluripotential embryonic stem cells that are carried to the orbit by blood circulation and escape regulatory influences, or from primordial germ cells that aim toward the pineal gland, even though other theories have also been proposed.[6] Orbital teratomas reported so far have been unilateral, and tumors cited as bilateral seem to have been limbal dermoids.[7]

Epidemiology

Teratomas account for 6.6% of childhood tumors, most commonly occurring in the testes, ovaries, and retroperitoneum; the orbit is a very rare site. A review of the literature showed that females are affected more than males in an approximately 2:1 ratio, with a propensity of the tumor to occur more frequently in the left than in the right orbit.[8] Most cases reported in the literature are cytologically benign, however in some cases, tumors may grow rapidly, and severe complications may ensue.[9]

Classification

Classification of Orbital Teratomas by Mizuo[10] and Duke-Elder[1];

- A complete fetus implanted in the orbit (orbitopagus parasiticus).

- A portion of a second fetus in the orbit.

- A tumor consisting of all three germinal layers.

- Tumors containing representatives of two germinal cell layers only.

- Tumors containing representatives of one layer only (dermoid cysts, osteomata, chondromata, etc.).

This classical system of classification has been modified by Damato[11] where the last sub-category was removed and it includes only four categories.

Diagnosis

Clinical presentation

Extreme unilateral proptosis in an otherwise healthy newborn with marked stretching of the eyelids over a tense, fluctuating mass, elongation of the palpebral fissure, normally developed eye that may exhibit degenerative changes secondary to the displacement by the teratoma, and transillumination of all or part of the orbital mass.[12] Most tumors are intraconal and stretch the four recti, which results in a quadrangular shape and axial proptosis. The eye might be buried within the tumor itself, and only the cornea or a narrow rim of the sclera visible. Exposure keratopathy, ulceration, keratoiritis, and even spontaneous perforation occur secondarily. The proptosis may be axial or vertical.[13]

The eye is usually normally formed, but displaced superiorly and forward. In rare cases there is no organized eye, with only remnants of ocular tissues being present.[14] The persistent enlargement of this neoplasm is attributed to mucus secretion from the embryonic intestinal tissue.[15] The optic nerve may be encased or adherent to the tumor, leading to secondary atrophy and poor pupil reaction.[16]Commonly the eye is normally developed but often vision is not preserved either due to optic atrophy or corneal exposure, probably to the amniotic fluid.

Other features include; no family history of congenital deformities with non-consanguineous parents and normal siblings, normal pregnancy and delivery, no history of teratogenic influences to the mother.[17]

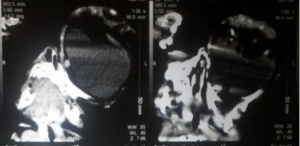

Radiological Finding

Upon imaging, benign orbital teratomas usually reveals multiloculated, cystic masses with an admixture of tissues including calcification, fat and ossification.[18] In some instances, CT would show a well-defined mass with focal areas of calcifications without bony erosion. Orbital MRI demonstrates variable signal intensities, but is valuable to ascertain intracranial involvement. Radiologic examinations are essential for a prompt diagnosis: MRI is the criterion standard and is usually correlated with a CT scan.[19]

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of orbital teratoma includes microphthalmos with cyst, dermoid cyst, epidermoid inclusion cysts, hemangioma, lymphangioma, cephalocele, neuroblastoma, rhabdomyosarcoma and retinoblastoma.[18][20] Microphthalmos with cyst is distinguished on the basis of a small globe in conjunction with a communicating channel between it and an attached cyst.[19]Dermoid cysts are unilocular and have a single fat-fluid level. Epidermoid inclusion cysts, probably because of their proteinaceous contents, are usually similar in appearance to water or cerebral spinal fluid on CT. Lymphangiomas are multilocular, but do not contain fat or calcification. Cephaloceles contain cerebral spinal fluid and generally have adjacent osseous abnormalities, but unlike teratomas and dermoids, cephaloceles do not contain lipid.[18]Rhabdomyosarcoma, neuroblastoma and retinoblastoma should be considered in children presenting after the newborn period. The first two show evidence of bone destruction and the latter intraocular mass lesion or calcification.[20]

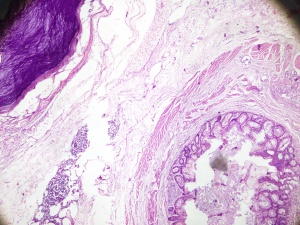

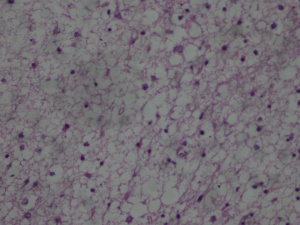

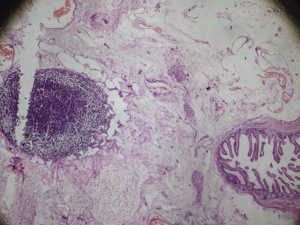

Histopathological Findings

Histopathological analysis of representative tissues makes the definite diagnosis of teratoma. Histologically, teratomas are composed of tissues derived from the three germinal layers.[6],[21] The predominant germ cell types observed in orbital teratoma are surface ectoderm producing squamous epithelium-lined cyst, hair follicles, and sweat glands. Neuroectodermal tissues include primitive neural tubes, choroidal plexus, and ganglia. Mesoderm is the next most common cell layer represented by the muscle, bone, cartilage, and fat. Endoderm is the least common and may produce gastrointestinal tissue cysts lined by respiratory-type pseudostratified columnar epithelium. Cystic spaces lined by glandular epithelium are responsible for the rapid enlargement of the lesions.[17]

Management

The clinical management of these lesions is unclear, due in part to their low incidence and to an incomplete understanding of their natural history.[22] Complete surgical excision of the tumor is the only acceptable treatment.

Surgery

Early surgery is mandatory to avoid permanent sequelae. The treatment is complete tumor excision with sparing of the eye, if possible. In the past, many surgeons preferred orbital exenteration because of malignant potential.[23][24] It is hard to recommend a fixed management plan; however, a common agreement in the management objectives should be to save the eye, retain some vision, encourage normal orbitofacial development, and to maintain good cosmetic result.[17]

Malignant teratomas and intracranial extension

Most of the orbital teratomas are benign. Only few cases of orbital teratomas with malignant changes have been reported.[24][25] [26][27]Histopathological examination revealed malignant sarcomatous changes in these variants.[24] Teratoma is considered malignant when the tissue is embryonal or immature in nature.[20] There is controversy on the diagnostic value of serum alpha-fetoprotein for mature teratomas,[28] especially in the newborn period, being normally high as a result of fetal production.[29] However, elevated serum alpha-fetoprotein levels may signal the presence of regional recurrence or metastatic disease in the setting of malignant teratoma.[30] Usually orbital teratoma is limited within the orbital cavity but there were also reported instances with intracranial involvement termed as orbito-cranial teratomas.[31]

Follow up and prognosis

Orbital teratomas have been known to recur and may undergo malignant degeneration. Therefore, close follow-up is necessary.[15] Follow up is necessary not only to ascertain recurrence but also to encourage normal orbito facial development and maintain cosmesis.

The prognosis of the orbital teratoma is related to several factors including the age, site, and grade of immaturity, and is usually good if complete excision is performed early in neonatal life.

Additional Resources

© Simanta Khadka.

Khadka S, Shrestha GB, Gautam P, Shrestha JB. Orbital Teratoma: A rare congenital tumour. Nepalese Journal of Ophthalmology. 2017 Jun 20;9(1):79-82.

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 Duke-Elder S: System of Ophthalmology, Vol. 3, Normal and Abnormal Development, Part 2. London, Henry Kimpton, 1964, pp 966-975.

- ↑ Holmes T. Congenital tumor removed from the orbit. Trans. Pathol. Soc. London. 1863;14:248.

- ↑ Broer WC, Weigert C. Teratoma orbitae congenitum. Virchows Arch Pathol Anat. 1876;67:518-22.

- ↑ Lawson G, London TP. Congenital Tumour of the Orbit; Complete Exophthalmos in a Child 2 Days Old: Removal of Eye. Trans. Path. Soc. London. 1884;35(379):1883-4.

- ↑ Prym P: Teratom der Schadel-und Augenhole beim Neugeborenen. Med Klin.1924;31:1093.

- ↑ Jump up to: 6.0 6.1 Gonzalez-Crussi F: Extragonadal Teratomas, in Hartmann WH, Cowan WR (ed): Atlas of Tumor Pathology. Washington, Armed Forces Institute of Pathologv, 1982, 2nd Seryes, 18th Fast, pp l-49, 100-108.

- ↑ Gemolotto G, Gaipa M: Quadro bilaterale di teratoma epibulbare associate a malformazioni palpebrali. Arch Ottalmol,1956, 60:161-170.

- ↑ Sesenna E, Ferri A, Thai E, Magri AS. Huge orbital teratoma with intracranial extension: a case report. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2010 May 1;45(5):e27-31.

- ↑ Bilgic S, Dayanir V, Kiratli H, Güngen Y. Congenital orbital teratoma: a clinicopathologic case report. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1997 Jun;13(2):142-6.

- ↑ Mizuo G. Eine seltene Form von Teratoma orbitae (Foetus in Orbita: Orbitopagus parasiticus). Arch Augenheilkd. 1910;65:365-83.

- ↑ Damato PJ, Damato FJ. Neonatal orbital teratoma. The British journal of ophthalmology. 1962 Nov;46(11):685.

- ↑ Hoyt WF, Joe S. Congenital teratoid cyst of the orbit. Arch Ophthalmol. 1962;68(19620):1.

- ↑ Kivelä T, Tarkkanen A. Orbital germ cell tumors revisited: a clinicopathological approach to classification. Survey of ophthalmology. 1994 May 1;38(6):541-54.

- ↑ Sreenan C, Johnson R, Russell L, Bhargava R, Osiovich H. Congenital orbital teratoma. American journal of perinatology. 1999;16(05):251-5.

- ↑ Jump up to: 15.0 15.1 Patel B: Benign orbital tumors: teratoma; in Perry J, Singh A (eds): Clinical Ophthalmic Oncology: Orbital Tumors, vol 1. Berlin/Heidelberg/New York/Dordrecht/London,Springer, 2014, pp 83–84.

- ↑ Pellerano F, Guillermo E, Garrido G, Berges P. Congenital Orbital Teratoma. Ocular oncology and pathology. 2017;3(1):11-6.

- ↑ Jump up to: 17.0 17.1 17.2 Gnanaraj L, Skibell BC, Coret-Simon J, Halliday W, Forrest C, DeAngelis DD. Massive congenital orbital teratoma. Ophthalmic Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery. 2005 Nov 1;21(6):445-7.

- ↑ Jump up to: 18.0 18.1 18.2 Herman TE, Vachharajani A, Siegel MJ. Massive congenital orbital teratoma. Journal of Perinatology. 2009 May;29(5):396.

- ↑ Jump up to: 19.0 19.1 Singh U, Subramanian A, Bal A. Congenital orbital teratoma presenting as microphthalmos with cyst. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2009 Nov;57(6):474.

- ↑ Jump up to: 20.0 20.1 20.2 Hann LE, Borden S, Weber AL. Orbital teratoma in the newborn A case report. Pediatric radiology. 1977 Sep 1;5(3):172-4.

- ↑ Mamalis N, Garland PE, Argyle JC, Apple DJ. Congenital orbital teratoma: a review and report of two cases. Survey of ophthalmology. 1985 Jul 1;30(1):41-6.

- ↑ Lee GA, Sullivan TJ, Tsikleas GP, Davis NG. Congenital orbital teratoma. Aust NZJ Ophthalmol 1997; 25: 63-6.

- ↑ Rose GE, Wright JE. Exenteration for benign orbital disease. British journal of ophthalmology. 1994 Jan 1;78(1):14-8.

- ↑ Jump up to: 24.0 24.1 24.2 Mahesh L, Krishnakumar S, Subramanian N, et al. Malignant teratoma of the orbit: a clinicopathological study of a case. Orbit 2003;22: 305-9.

- ↑ Garden JW, McMANIS JC. Congenital orbital-intracranial teratoma with subsequent malignancy: case report. British journal of ophthalmology. 1986 Feb 1;70(2):111-3.

- ↑ Saradarian AV. Malignant teratoma of the orbit; six and one half years' observation. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill.: 1929). 1947 Feb;37(2):253.

- ↑ Soares EJ, Silva Lopes KD, Andrade JD, Faleiro LC, Alves JC. Orbital malignant teratoma: a case report. Orbit. 1983 Jan 1;2(4):235-42.

- ↑ Tsuchida Y, Hasegawa H. The diagnostic value of alpha-fetoprotein in infants and children with teratomas: a questionnaire survey in Japan. Journal of pediatric surgery. 1983 Apr 1;18(2):152-5.

- ↑ Heerema-McKenney A, Bowen J, Hill DA, Suster S, Qualman SJ. Protocol for the examination of specimens from pediatric and adult patients with extragonadal germ cell tumors. Archives of pathology & laboratory medicine. 2011 May;135(5):630-9.

- ↑ Frazier AL, Brodsky JR, Kanwar VS, Stafford LM, Rahbar R. Germ cell tumors/teratoma. InPediatric Head and Neck Tumors 2014 (pp. 153-163). Springer, New York, NY.

- ↑ Sesenna E, Ferri A, Thai E, Magri AS. Huge orbital teratoma with intracranial extension: a case report. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2010 May 1;45(5):e27-31.