All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Disease

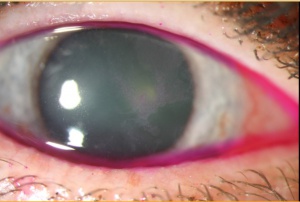

Ocular surface squamous neoplasia (OSSN) encompasses a wide and varied spectrum of disease involving abnormal growth of dysplastic squamous epithelial cells on the surface of the eye (Figure 1).

- Conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) is non- invasive by definition; the basement membrane remains intact and the underlying substantia propria is spared.[1] [2] It is a slow- growing tumor that arises from a single mutated cell on the ocular surface.[1]CIN is known by other names including Bowen’s disease, conjunctival squamous dysplasia, intraepithelial epithelioma, and epithelial dyskeratosis.[1]

- Corneal epithelial dysmaturation, corneal epithelial dysplasia, and corneal intraepithelial neoplasia refer to neoplastic lesions of the cornea in which the conjunctival presence is minimal. The corneal epithelial islands or geographic epithelial granularity are the predominant clinical findings.[2]

- Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) describes a malignant lesion in which the dysplastic epithelial cells have penetrated the corneal basement membrane, gaining metastatic potential.

- Mucoepidermoid carcinoma represents a rare yet aggressive variant of SCC. It is, however, clinically indistinguishable from SCC and must be differentiated by histopathologic sampling.

Epidemiology

According to epidemiology studies, the prevalence of OSSN is estimated to range from <0.2 cases/million/year (UK, 1996) to 35 cases/million/year (Uganda, 1992).[3] [4] In several series, CIN has been reported to be the most common conjunctival neoplasia, whereas SCC has been found to be the most common conjunctival malignancy.[5] In the western hemisphere, OSSN afflicts mainly Caucasian men in their 60s to 70s who live close to the equator.[6] However in Africa and certain parts of Asia, OSSN afflicts younger patients and tends to be more clinically aggressive.[5][7] A similar pattern has been observed in patients with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and xeroderma pigmentosum.

Etiology and Risk factors

The etiology of OSSN appears to be multifactorial, and likely involves a variety of environmental factors in a susceptible host. In addition to the proposed etiologies discussed below, smoking, light hair and skin, xerophthalmia (Vitamin A deficiency) and exposure to petroleum products have been implicated in the pathogenesis of OSSN.[1]

Ultraviolet light

It is well recognized that the prevalence of OSSN is increased in populations that live within 30- degrees latitude from the equator.[5] [6] In addition, OSSN is more common in Caucasians with light complexions and patients with xeroderma pigmentosum, a genetic condition that increases susceptibility to DNA alterations secondary to UV light.[8] Furthermore, ocular lesions are most commonly located within the sun- exposed interpalpebral fissure, specifically in the nasal or temporal zones.[1] Despite the evidence, it is unclear why UV light, a common environmental exposure, results in OSSN in some patients but not others. It is likely that it acts as a cellular insult in an already susceptible host.

Immunosuppression/ HIV

In Africa, studies have shown an HIV infection rate as high as 79% in patients with OSSN compared to 14% in the general population.[9] In the United States, a study done at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute found that OSSN may be a possible marker for undiagnosed HIV. [5] The study found that half of patients diagnosed with OSSN under the age of 50 were seropositive for the virus.[5]. Both HIV 1 and 2 have been implicated.

Human papillomavirus (HPV)

The association of HPV with OSSN remains unclear. Although some studies have shown a clear association of OSSN with HPV, other studies have not. [10] [11]Whereas HPV 6,8, and 11 have been linked with benign conjunctival epithelial lesions, HPV 16 and 18 have been associated with malignant neoplastic lesions.[1] However, HPV status does not appear to correlate to treatment response.

Mutation or deletions of tumor suppressor gene p53.

Mutations of p53, a tumor suppressor gene, are thought to be the most common genetic anomalies in human malignancies. [1] Some have hypothesized that HPV or UV-B may alter p53, resulting in the development of OSSN in susceptible individuals.[7]

General Pathology

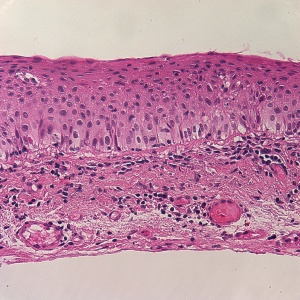

- CIN refers to varying degrees of conjunctival epithelial dysplasia. For instance, CIN I represents mild disease, CIN II refers to moderate disease, and CIN III (Figure 2) suggests near full- thickness epithelial involvement.[2] CIN that involves the entire epithelium is referred to as carcinoma-in-situ. Histologically, CIN lesions contain a mixture of spindle cells and epidermoid cells.[1] There is disorganization of the cells, abnormal polarity, and a mild to marked increase in the nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio.[1] Mitotic figures are sometimes seen.[1] On pathology, there is a characteristic sharp demarcation line between normal and abnormal epithelium. These features are absent in squamous papillomas.

- In corneal epithelial dysmaturation there may be slightly abnormal nuclear to cytoplasmic ratios and dyskeratosis. In contrast, there is cellular disorganization, dysmaturation, and atypia with increased nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio in corneal epithelial dysplasia.[1]

- CIN is often the precursor to conjunctival SCC. Due to a barrier provided by Bowman’s membrane, subepithelial cellular invasion is almost exclusively limited to the conjunctiva.[1] Histologically, there is replacement of normal epithelium with disorganized, dyskeratotic, and acanthotic cells with penetration of the basement membrane.

- Mucoepidermoid carcinoma represents a particularly aggressive variant of SCC. On pathology, dysplastic squamous cells and malignant goblet cells are seen with mucin stains.[2] Lesions with predominant mucin elements are thought to be less clinically aggressive.[1]

Diagnosis

History

- Patients are often unaware of the presence of an OSSN lesion, and diagnosis is made only on careful, routine ophthalmic examination. However, patients may complain of redness and variable degrees of ocular irritation secondary to inflammation.

Clinical examination

The clinical presentation of OSSN is variable, making diagnosis sometimes difficult. Typically, patients present with a gelatinous or plaque like interpalpebral conjunctival gray or white lesion.[7] Approximately 95% of CIN lesions occur at the limbus, where the most actively mitotic cells reside.[1] The lesion may be flat or elevated and may be associated with feeder vessels. Fluorescein, lissamine green, or Rose Bengal are often used to highlight the lesion (Figure 3).[2] Abnormal or dysplastic epithelium have a diffuse, granular appearance, differentiating it from normal epithelium.[1]

- There are three major clinical variants of CIN: papilliform, gelatinous, or leukoplakic.[1] These categories are not mutually exclusive and may overlap. Leukoplakia refers to whitening and thickening of the tumor’s surface as a result of surface hyperkeratinization. However, most CINs present as gelatinous with hairpin configuration of the associated conjunctival vessels. This configuration is in contrast to the “red- dot” or “strawberry” pattern seen in squamous papillomas.[1] There may also be associated pigment within the lesion, resulting in an erroneous diagnosis of melanoma especially in individuals with darker complexions.[1]

- Corneal involvement is the result of the spread of abnormal epithelium from the adjacent limbus. The abnormal squamous cells often have a translucent, grayish, frosted appearance. In addition, the corneal lesions often take on a characteristic fimbriated or pseudopodia configuration.[2] There is often an adjacent neoplastic pannus present to metabolically support these abnormal cells. Primary corneal dysplasia and primary corneal epithelial dysmaturation are used to describe lesions that have disproportionately little conjunctival involvement. Typically in these benign lesions, there is an absence of a corneal pannus.[1] These lesions may be stationary or slowly progressive.[1]

- SCC presents similarly to CIN; however, the conjunctival lesion tends to be immobile and more raised in appearance. The presence of a large feeder vessel is suggestive of epithelial basement membrane violation. Rarely, SCC may present as bilateral lesions, which are typically keratinized and papillary in appearance.[1]

- Mucoepidermoid carcinoma appears clinical identical to SCC; however, it may arise anywhere on the ocular surface rather than in the typical limbal zone seen in CIN and SCC. Due to the difficulty of diagnosis, most cases are made after multiple recurrences of presumed SCC.[1] Mucoepidermoid carcinoma tends to more invasive than SCC, with reports of ocular and orbital penetration; however, metastases to the lymph nodes have been documented.[1]

Imaging modalities

- Optical coherence tomography (OCT) has been employed as an in vivo diagnostic modality in the detection of OSSN. There are distinctive features of OSSN, such as hyper reflectivity, thickened epithelium, and abrupt transition from normal to abnormal tissue seen on ultra high resolution OCT that differentiates it from other conjunctival lesions such as pterygia (Figure 4).[12]

- Impression cytology have been reported in the literature as a noninvasive method to diagnose and clinically monitor patients with OSSN. However, it can only assess superficial tissue and is unable to discern the depth of involvement.[12]

- Confocal microscopy has also been reported to be helpful in guiding treatment since it is able to reveal cellular details. Its disadvantages include difficulty of use and limited field of view.[12]

- High frequency ultrasound may be helpful in determining the extent of invasion into the eye in cases of SCC.[1]

Management

General treatment

The onset of the lesion, whether the lesions represents a recurrence, and prior treatments dictate tumor management. Major breakthroughs in the diagnosis and clinical approach of this disease has occurred within the past 2 to 3 decades.[6] There has been an increasing trend towards employing medial therapy over surgery.

Medical therapy

The use of topical chemotherapeutic agents, including Interferon-α2b, mitomycin C, and 5- fluorouracil, has the advantage of treating the entire ocular surface and avoiding surgical complications such as positive margins, scarring, and limbal stem cell deficiency.

- Interferon-α2b (IFNα2b) is a cytokine produced by immune cells to combat microbes and viruses. It’s mechanism of action is thought to be related to its antiproliferative, cytotoxic, antiviral, and antigenic properties.[13] It may be injected subconjunctivally or used topically as an eye drop. Subconjunctival injections, concentrated at 3 million IU/0.5 mL, are administered weekly until resolution of the lesion. The concentration for the topical eye drop is typically 1 million IU/mL. Topical treatment is administered 4 times daily until 1-2 months after resolution of the lesion, which takes 4 months on average.[14] The efficacy rate after topical IFNα2b ranges from 80% to 100%.[15] Unfortunately, although well tolerated, topical IFNα2b is only available through specialized compounding pharmacies, requires refrigeration, and is costly.

- 5- fluorouracil (5-FU) blocks DNA synthesis by acting as a pyrimidine analog after incorporation into RNA.[13] Its efficacy rate has been reported to be 100% after one to five cycles (1 month on and 3 months off), with a recurrence rate of up to 20%.[16] Another regimen that causes less inflammation to the ocular surface involves cycling the medication 4 times daily for 4 to 7 days followed by a 3-week holiday. [17] [18] Treatment with 5-FU is less costly than MMC and IFNa2b and also has a favorable side effect profile compared with MMC. Disadvantages include mild ocular irritation and occasional conjunctivitis. Topical corticosteroids and preservative free artificial tears may be co-administered to reduce these side effects.[14]

- Topical mitomycin C (MMC) has proven to be an efficacious treatment of OSSN. Mitomycin C is an antimetabolite that alkylates DNA and disrupts the production of RNA.[13] Studies have reported its efficacy rate to range from 80% to 100%.[13] MMC comes in either 0.02% or 0.04%. The lower concentration is usually prescribed continuously for a month; whereas, the higher concentration may be used for a week followed by 2 to 3 weeks off treatment. It must be refrigerated. While clinical resolution and recurrence rates are similar to IFN, the time to resolution is typically shorter with MMC.[14] The disadvantages of MMC includes ocular pain, possible limbal stem cell loss, and other ocular surface toxicity. Punctal plug occlusion is advised to decrease the risk of punctual stenosis.

- Reports have shown that both topical and subconjunctival injections of anti- vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) to be efficacious in treating OSSN. One case series reported improvement in the size and vascularity of conjunctival OSSN after 3 months of treatment with subconjunctival injections of bevacizumab with little effect on cornea involvement.[19] Another small case series reported significant reduction in the size of the lesion with the use of topical bevacizumab in 10 eyes after 5 to 14 weeks.[20]

Surgery

A no touch technique is used during excision of OSSN lesions. CIN and SCC lesions involving the limbus should be excised with at least a 3-4mm uninvolved conjunctival margin. A large conjunctival margin is important since seemingly uninvolved tissue clinically may still contain dysplastic cells. Absolute alcohol is then applied to the cornea to loosen the epithelium from the basement membrane, and then rinsed off with copious irrigation after 30 to 40 seconds. All involved corneal epithelium and any associated corneal pannus is then scraped off with a Beaver blade or surgical sponge after instillation of absolute alcohol to loosen the cells.[2] It is very important that the underlying Bowman’s layer is not violated during this process. Using a double or triple rapid freeze- thaw technique, cryotherapy is applied to the conjunctival edges, involved limbal zone, and the bare scleral bed to kill any remaining dysplastic cells.[1] Cryotherapy is very important since it effectively extends the surgical margins. If the margins return positive or there are any concerns for residual disease, topical chemotherapy may be used after excision. Both epithelial dysmaturation and corneal epithelial dysplasia are considered benign lesions, and are treated with corneal scraping and wide conjunctival limbal margins if involved. In cases of SCC, a thin lamellar scleral flap after the removal of the conjunctival lesion is advised followed by application of absolute alcohol to the scleral bed.[2] The area of surgical resection may be left open or closed with amniotic membrane graft.[2] In cases of local invasion into the eye or orbit, enucleation and exteneration may be done in collaboration with an oculoplastics surgeon.[1] Sentinel node biopsy may also be appropriate to stage the disease.[1] Radiation may be considered as adjunctive therapy in certain cases that have been recalcitrant to other modalities of treatment.

Differential Diagnosis

- Pterygium

- Pinguecula

- Pannus

- Actinic keratosis

- Bitot spots (xerophthalmia)

- Benign intraepithelial dyskeratosis

- Pyogenic granuloma

- Conjucntival/ limbal cyst

- Conjunctival Hemagioma

- Keratoacanthoma

- Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia

- Malignant melanoma

- Naevus

Prognosis

The recurrence rate of OSSN after surgical excision can occur in over half of cases and may occur years later.[21] The rate of recurrence is substantially higher in the setting of positive surgical margins. Even if the surgical margins are negative, up to one- third of eyes may experience a recurrence within 10 years.[21] The conjunctival lesions that tend to fare the worst involve over half of the limbal stem cells.[1]

A recurrent OSSN can grow rapidly and be more invasive, and thus needs to be treated with aggressive medical, surgical, or combination therapy.[1] The conjunctival lesions that tend to fare the poorest involve over half of the limbal stem cells.[1] Overall, SCC is generally associated with local invasion rather than wide- spread systemic metastases.

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 1.23 1.24 1.25 1.26 1.27 1.28 1.29 Krachmer JH, Mannis MJ, Holland EJ. Cornea: Fundamentals, diagnosis and management. 2005.

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 Reidy JJ, Bouchard CS, Florakis GJ, et al. Basic and Clinical Science Course, 2011-2012. 2011:226–233.

- ↑ Ateenyi-Agaba C. Conjunctival squamous-cell carcinoma associated with HIV infection in Kampala, Uganda. The Lancet 1995;345:695–696.

- ↑ Newton R, Reeves G, Beral V, et al. Effect of ambient solar ultraviolet radiation on incidence of squamous-cell carcinoma of the eye. The Lancet 1996;347:1450–1451.

- ↑ Jump up to: 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Karp CL, Scott IU, Chang TS, Pflugfelder SC. Conjunctival Intraepithelial Neoplasia: A Possible Marker for Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection? Arch Ophthalmol 1996;114:257–261.

- ↑ Jump up to: 6.0 6.1 6.2 Basti S, Macsai MS. Ocular surface squamous neoplasia: a review. Cornea 2003;22:687–704.

- ↑ Jump up to: 7.0 7.1 7.2 Kiire CA, Srinivasan S, Karp CL. Ocular Surface Squamous Neoplasia. International ophthalmology clinics 2010;50:35–46.

- ↑ Lee GA, Williams G, Hirst LW, Green AC. Risk factors in the development of ocular surface epithelial dysplasia. Ophthalmology 1994;101:360–364.

- ↑ Spitzer MS, Batumba NH, Chirambo T, et al. Ocular surface squamous neoplasia as the first apparent manifestation of HIV infection in Malawi. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol 2008;36:422–425.

- ↑ Carrilho C, Gouveia P, Yokohama H, et al. Human papillomaviruses in intraepithelial neoplasia and squamous cell carcinoma of the conjunctiva. European Journal of Cancer Prevention 2013;22:566–568.

- ↑ Galor A, Garg N, Nanji A, et al. Human Papilloma Virus Infection Does Not Predict Response to Interferon Therapy in Ocular Surface Squamous Neoplasia. Ophthalmology 2015;122:2210–2215.

- ↑ Jump up to: 12.0 12.1 12.2 Thomas BJ, Galor A, Nanji AA, et al. Ultra high-resolution anterior segment optical coherence tomography in the diagnosis and management of ocular surface squamous neoplasia. The Ocular Surface 2014;12:46–58.

- ↑ Jump up to: 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Nanji AA, Sayyad FE, Karp CL. Topical chemotherapy for ocular surface squamous neoplasia. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2013;24:336–342.

- ↑ Jump up to: 14.0 14.1 14.2 Al Bayyat, G., Arreaza-Kaufman, D., Venkateswaran, N. et al. Update on pharmacotherapy for ocular surface squamous neoplasia. Eye and Vis 6, 24 (2019).

- ↑ Galor A, Karp CL, Chhabra S, et al. Topical interferon alpha 2b eye-drops for treatment of ocular surface squamous neoplasia: a dose comparison study. British Journal of Ophthalmology 2010;94:551–554.

- ↑ Midena E, Angeli CD, Valenti M. Treatment of conjunctival squamous cell carcinoma with topical 5-fluorouracil. British journal of Ophthalmology 2000;84:268–272.

- ↑ Yeatts RP, Engelbrecht NE, Curry CD, et al. 5-Fluorouracil for the treatment of intraepithelial neoplasia of the conjunctiva and cornea. Ophthalmology 2000;107:2190–2195.

- ↑ Joag MG, Sise A, Murillo JC, Sayed-Ahmed IO, Wong JR, Mercado C, et al. Topical 5-fluorouracil 1% as primary treatment for ocular surface squamous neoplasia. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(7):1442–8.

- ↑ Faramarzi A, Feizi S. Subconjunctival bevacizumab injection for ocular surface squamous neoplasia. Cornea 2013;32:998–1001.

- ↑ Özcan AA, Çiloğlu E, Esen E, Şimdivar GH. Use of topical bevacizumab for conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia. Cornea 2014;33:1205–1209.

- ↑ Jump up to: 21.0 21.1 Tabin G, Levin S, Snibson G, et al. Late Recurrences and the Necessity for Long-term Follow-up in Corneal and Conjunctival Intraepithelial Neoplasia. Ophthalmology 1997;104:485–492.