Frontalis Suspension Procedure

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Surgical Therapy

Frontalis suspension is a frequently used surgical technique to correct moderate to severe drooping of the upper eyelid (blepharoptosis) in the presence of poor or absent levator muscle function. In this procedure, the connection between the eyelid margin and eyebrow is enhanced using a sling-type material as a suspender allowing the frontalis muscle to more effectively elevate the eyelid.

Background

Synthetic sutures were first used for frontalis suspension surgery in 1880.[1] In 1909, Payr was the first to introduce the use of autogenous fascia lata (FL) in congenital ptosis repair.[2] This technique was reintroduced by Wright in 1922.[3] Crawford modified Wright’s technique of frontalis suspension using FL in 1956 for use in children >3 years.[4] This led to the use of autogenous FL as the gold standard treatment in congenital ptosis associated with poor levator function, as it had good outcomes, low risk of recurrent ptosis and few complications. Increasingly, silicone thread has been a material of choice as it is low cost, does not require a second surgical site incision and can be used in all age groups. Patient Selection: The timing of surgical intervention in congenital ptosis is dependent on the patient’s age, unilaterally or bilaterally of ptosis, the severity of ptosis, and risk of amblyopia. In mild to moderate congenital ptosis without amblyopia, surgery can be deferred until the patient is at least 3 to 5 years old, to allow facial growth and maturation, as well as to ensure the patients’ cooperation during preoperative evaluation and measurements.[5] [6][7][8] In addition, in some older patients, the surgery may be performed under local anesthesia with sedation, which may allow improved intraoperative quantification of eyelid height and contour and therefore a better surgical outcome.

However, because 20–70% of patients with simple congenital ptosis will develop amblyopia[10][11][12] early surgical repair of congenital ptosis (Figure 1) is recommended to reduce this risk.[13] This is especially important in cases of unilateral congenital ptosis where maintenance of the unilateral brow elevation is an important component of eyelid elevation. In addition to the cosmetic aspects, the sleepy appearance in children with ptosis may have psychosocial effects which warrant more urgent surgical repair.[8][14] In patients with acquired moderate to severe ptosis secondary to a recent neurogenic or traumatic event, it is advised to wait at least 6 to 12 months before the surgical intervention to allow spontaneous recovery or improvement of function.[4]

Patient Selection

Indications

Frontalis suspension surgery is indicated for blepharoptosis with levator muscle function of 2 mm or less and no more than 6 mm by various authors.[15][16][17][18] [19][20] Frontalis suspension is commonly used for severe congenital ptosis. Treatment is critical when an eyelid blocks the visual axis causing amblyopia, or when an anomalous head posture is apparent. Frontalis suspension may also be used to treat blepharoptosis secondary to chronic progressive external ophthalmoplegia (CPEO), cranial nerve III palsy, blepharophimosis syndrome, Marcus Gunn jaw-wink phenomenon, congenital fibrosis syndrome, muscular dystrophy, myasthenia gravis, double levator palsy, and aponeurotic ptosis in elderly patients.[5][21]

Relative Contraindications

Poor Bell’s phenomenon (limited elevation of the eye with eyelid closure), reduced corneal sensitivity, or poor tear production can produce exposure keratopathy after a frontalis suspension procedure especially if the lid height is high. These patients may require an intentional under correction of eyelid position and close postoperative follow-up care to avoid corneal exposure, infection, corneal ulcer and amblyopia.

Surgical Planning

The decision to perform unilateral or bilateral surgery in cases of severe unilateral ptosis should be discussed with the patient and patient’s family if underage. A bilateral suspension procedure for severe unilateral congenital ptosis may optimize symmetry (especially if there is a poor elevation of the brow on the ptotic side). However, if there is enough unilateral brow elevation, a unilateral sling may be considered.

The use of autogenous FL (can be obtained from the leg of patients older than 3-5 years) is considered the gold standard treatment in congenital ptosis associated with poor levator function. However, FL harvesting can be technically difficult and leaves a scar. In some cases, an insufficient amount of FL may be harvested necessitating the use of alternative autogenous or alloplastic synthetic materials such as:

- Preserved (tissue bank) fascia lata

- Nonabsorbable suture material (e.g., 2-0 Prolene, Nylon (Supramid) or Mersilene)

- Silicone bands

- Silicone rods

- Silastic (silicone elastomer)

- ePTFE (expanded Poly Tetra Fluoro Ethylene)

- Gore-Tex

- Autogenous materials used less frequently include palmaris longus tendon and temporalis fascia.

Synthetic materials may be preferred in children younger than 3 years or for patients who do not want an additional harvesting operation.

Surgical Technique

The frontalis sling operation includes:

- Patient preparation

- Decision regarding open or closed approach

- Skin incision markings

- Decision to suture the sling to tarsus or not

- Passing the suture to the brow

- Skin crease closure

- Adjustment of height and contour

- Closure of forehead incisions

The operation is usually performed under general anesthesia in children but can be performed under local anesthesia with sedation in adults.

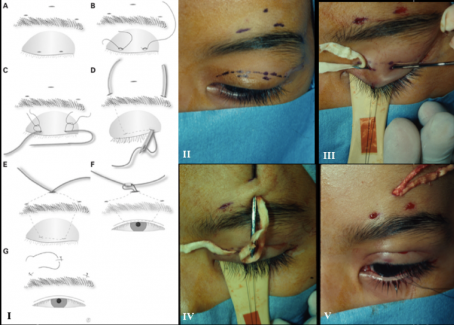

A 50:50 mixture of 2% xylocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine, 0.5% Marcaine with 1:200,000 epinephrine and hyaluronidase is injected in the area of the upper eyelid and suprabrow area. A marking pen is used to mark the intended skin incisions (Figure 2). These incisions maybe 3 to 5 small stab incisions or incorporate a blepharoplasty incision. Once the incisions have been marked, a

5-0 or 6-0 silk traction suture is placed, and the lid placed on downward tension. If a blepharoplasty is to be performed, a #15 Bard Parker blade is used to incise the skin and the cutting mode of cautery used to excise skin. The orbital septum may be incised and some preaponeurotic fat trimmed according to the plan outlined prior to surgery.

In this open technique, an orbicularis muscle flap at the anterior inferior one-third of tarsus is raised and the anterior surface of the tarsus revealed. The sling material is then sutured to the tarsus using a 6-0 vicryl suture. The sling material is then passed under the orbital septum near the arcus marginalis and out the of the brow incisions using either the needles attached to the silicone sling or a Wright needle. The skin crease is created by suturing skin to orbicularis to sling and then orbicularis and skin using skin crease-forming sutures. The sling is externalized at the central subrabrow incision, tightened, cut and buried ensuring appropriate height and contour of the eyelid margin. The brow incisions are closed.

If a blepharoplasty is not performed the sling is placed sequentially through each of the three or five stab incisions in the fashion of a trapezoid. The ends are externalized at the superior most aspect, tied and cut. The ends are buried, and the incisions closed.[22][23]

In an attempt to enhance the aesthetic outcome of the surgery by removing visible forehead stab incisions, Dr. Soosan Jacob and Dr. Amar Agarwal described a modification to the conventional Fox pentagon. In this supra-brow single stab incision technique, the internal pentagon shape is delineated by using two curved non-toothed forceps placed at the intended lid margin points to lift the lid along the tentative vertical arms of the pentagon. Height and contour are assessed, and if contour is flat or peaked or undesirable with respect to the location of greatest height of arch, the separation between margin points as well as angle of the arms connecting the margin points to the medial and lateral suprabrow points is adjusted until a desirable contour is achieved. This technique provides for a consistent lid crease and contour with a single small supra/adjacent brow incision and is an elegant refinement of a classic procedure. It allows the single suprabrow incision to be almost invisible. This provides an aesthetic advantage over the conventional three stab supra-brow or forehead incision.[24] In our experience, this technique is ideal for pediatric congenital ptosis and less easily used in adult ptosis where the larger lid lengths makes passing of the sling in a subcutaneous trapezoidal configuration more challenging (Figures 3-8).

Outcomes

To date, FL and SRs have been used with much success in the treatment of congenital ptosis. A recent study by Lee et al found better cosmetic results and lower recurrence rate with SRs compared to preserved FL in a Korean population.[10] Patients may not be able to close their eyelids during sleep from a few weeks to several months following surgery. Families should be informed of this outcome before the operation. The concern of open lids during sleep improves with time and is generally not an issue in the pediatric population; lubrication may be needed to avoid exposure keratopathy especially in the adult population with CPEO or a poor Bell’s phenomenon. Recurrent ptosis rates have been reported to be as low as 5% with the use of autogenous fascia lata, and 8% with the use of banked fascia lata.[18][25] Reports have indicated that autogenous fascia and alloplastic materials resulted in similar functional and cosmetic results in frontalis suspension surgery.[5][21] In addition, a recent review study suggested that PTFE is the material with the lowest recurrence rates as well as good cosmetic and functional results[26] though this material has not gained wide acceptance.

Complications

Thigh wound hematomas or muscle herniation can occur during harvesting the fascia lata. The use of nonautogenous SR can lead to potential foreign body tissue reaction (such as granuloma formation), extrusion, and wound infection. Frontalis suspension procedures produce lagophthalmos in most cases and recurrence of ptosis is not uncommon.[16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27] It is anticipated that children with severe congenital ptosis will require multiple procedures over their lifetime as they “grow out” of their surgery. The slings may loosen or cheese wire necessitating additional procedures as the child grows. However in general, frontalis suspension procedures are an effective technique for severe congenital and acquired ptosis.

References

- ↑ Dransart HN. Un cas de blépharoptose opéré par un procédé spécial à l’auteur. Guerison. Analectes Ophtalmologiques. 1880; 84:88. (German)

- ↑ Payr E. Plastik mittels freier Faszientransplantation bei Ptosis. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1909; 35:822. (German)

- ↑ Wright WW. The use of living sutures in the treatment of ptosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1922; 51:99–102.

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 Crawford JS. Repair of ptosis using frontalis muscle and fascia lata. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1956; 60:672–8.

- ↑ Jump up to: 5.0 5.1 5.2 Finsterer J. Ptosis causes presentation and management. Aesth Plast Surg. 2003; 27:193–204.

- ↑ Putterman AM, Dresner SC, Meyer DR, Wobig JL, Dailey RA. Surgery for the upper eyelid and the brow. In: Wobig JL, Dailey RA, editors. Oculofacial Plastic Surgery. New York: Thieme; 2004. pp. 54–82.

- ↑ Custer PL. Ptosis levator muscle surgery and frontalis suspension. In: Chen WP, editor. Oculoplastic Surgery The Essentials. New York: Thieme; 2001. pp. 89–100.

- ↑ Jump up to: 8.0 8.1 Ahmadi AJ, Sires BS. Ptosis in infants and children. Into Ophthalmol Clin. 2002; 42:15–29.

- ↑ Ahn J, Kim NJ, Choung HK, Hwang SW, Sung M, Lee MJ, Khwarg SI. Frontalis sling operation using silicone rod for the correction of ptosis in chronic progressive external

- ↑ Jump up to: 10.0 10.1 Gusek-Schneider GC, Martus P. Stimulus deprivation amblyopia in human congenital ptosis a study of 100 patients. Strabismus. 2000; 8:261–70.

- ↑ Merriam WW, Ellis FD, Helveston EM. Congenital blepharoptosis, anisometropia, and amblyopia. Am J Ophthalmol. 1980; 89:401–7.

- ↑ Anderson RL, Baumgartner SA. Amblyopia in ptosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1980; 98:1068–9.

- ↑ Saunders RA, Grice CM. Early correction of severe congenital ptosis. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1991; 28:271–3.

- ↑ Hersh D, Martin FJ, Rowe N. Comparison of silastic and banked fascia lata in pediatric frontalis suspension. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2006; 43:212–8.

- ↑ Anderson RL, Dixon RL. Aponeurotic ptosis surgery. Arch Ophthalmol. 1979; 97:1123–8.

- ↑ Jump up to: 16.0 16.1 Katowitz JA Frontalis suspension in congenital ptosis using a polyfilament, cable-type suture. Arch Ophthalmol. 1979; 971659- 1663.

- ↑ Jump up to: 17.0 17.1 Steinkogler FJ, Kuchar A, Huber E, Arocker-Mettinger E Gore-Tex soft tissue patch frontalis suspension technique in congenital ptosis and in blepharophimosis-ptosis syndrome. Plast Reconstr Surg.1993; 921057- 1060.

- ↑ Jump up to: 18.0 18.1 18.2 Wagner RS, Mauriello JA, Nelson LB, Calhoun JH, Flanagan JC, Harley RD. Treatment of congenital ptosis with frontalis suspension: a comparison of suspensory materials. Ophthalmology.1984; 91245- 248.

- ↑ Jump up to: 19.0 19.1 Crawford JS Repair of ptosis using frontalis muscle and fascia lata: a 20-year review. Ophthalmic Surg. 1977; 8 (4) 31- 40.

- ↑ Jump up to: 20.0 20.1 Beyer CK, Albert DM The use and fate of fascia lata and sclera in ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. Ophthalmology.1981; 88869- 886.

- ↑ Jump up to: 21.0 21.1 21.2 Wong VA, Beckingsale PS, Oley CA, Sullivan TJ. Management of myogenic ptosis. Ophthalmology. 2002; 109:1023–31.

- ↑ Jump up to: 22.0 22.1 Nerad, JA. Techniques in Ophthalmic Plastic Surgery pp. 221-224, Elsevier 2010

- ↑ Jump up to: 23.0 23.1 Orbit, Eyelids, and Lacrimal System. Basic and Clinical Science Course (BCSC). American Academy of Ophthalmology, 2018-2019; pp 220-221.

- ↑ Jump up to: 24.0 24.1 Jacob S, Agarwal A, Nair V, Karnati S, Kumar DA, Prakash G. Comparison of outcomes of suprabrow single-stab and 3-stab incision frontalis sling surgery. Asia-Pacific Journal of Ophthalmology. 2012; 1(2):91-96.

- ↑ Jump up to: 25.0 25.1 Crawford JS Frontalis sling operation. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1982; 19253- 255.

- ↑ Jump up to: 26.0 26.1 Pacella E, Mipatrini D, Pacella F, Amorelli G, Bottone A, Smaldone G, et al. Suspensory materials for surgery of blepharoptosis: a systematic review of observational studies. PLoS One. 2016; 11(9): e0160827.

- ↑ Takahashi Y, Leibovitch I, and Kakizaki H. Frontalis Suspension Surgery in Upper Eyelid Blepharoptosis. Open Ophthalmol J. 2010; 4: 91–97.