Congenital Hypertrophy of the Retinal Pigment Epithelium

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Congenital hypertrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium (CHRPE) is a generally asymptomatic congenital hamartoma of the retina with typical (solitary, grouped) and atypical variants. Though CHRPE is typically benign, the atypical variant is associated with familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), an autosomal dominant cancer syndrome.

Disease Entity

ICD-10: Q14.1 - congenital malformation of the retina.

Disease

Congenital hypertrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium is a typically benign, asymptomatic, pigmented fundus lesion. A congenital hamartoma of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), CHRPE occurs in 3 variant forms: solitary (unifocal), grouped (multifocal), and atypical. While other forms are benign, atypical CHRPE is associated with familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), an autosomal dominant cancer syndrome, and is characterized by numerous adenomatous polyps of the colon and rectum. Left untreated, virtually all FAP patients develop colorectal carcinoma by middle age. Familial adenomatous polyposis subtypes associated with atypical CHRPE include Gardner syndrome (FAP with skeletal hamartomas and various soft tissue tumors) and Turcot syndrome (FAP with various brain tumors).

Epidemiology

The prevalence of CHRPE in the general optometric population has been estimated to be 1.2%.[1] Atypical CHRPE is the earliest and most common extra-colonic manifestation of FAP, present in up to 90% of patients.[2][3]

General pathology

Mutations in the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene are responsible for FAP. The gene encodes a tumor suppressor protein and is located on the long arm of chromosome 5 (5q21–q22). The severity of disease and presence of extracolonic features are associated with the location of the APC mutation,[5] with the phenotypic expression of CHRPE in FAP regularly present with mutations between codons 446–1338 but absent with mutations between codons 1445–1578.[6]

Histopathology

Most solitary and grouped CHRPE lesions are characterized by a monocellular layer of hypertrophied RPE cells densely packed with large, round macromelanosomes.[7][8] Glial cells replace the RPE and photoreceptor layer in areas of depigmented lacunae, and the underlying Bruch’s membrane may be thickened; the overlying photoreceptor layer degenerates with increasing age.[7][9] The choroid, choriocapillaris, and inner retinal layers are unaffected.[10]

In comparison, atypical CHRPE lesions associated with FAP show RPE hypertrophy and hyperplasia, retinal invasion, and retinal vascular changes.[10] These lesions may be multilayered or involve the full thickness of the retina.[11][12]

Diagnosis

Congenital hypertrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium is usually an incidental finding made on routine ophthalmological examination. The identification of multiple or bilateral lesions should alert the clinician to the possibility of underlying FAP.

History

This condition is almost exclusively asymptomatic. A subset of patients may be known with FAP.

Physical Examination

Lesions are usually detected on dilated examination of the peripheral retina.

Signs

Solitary (Unifocal)

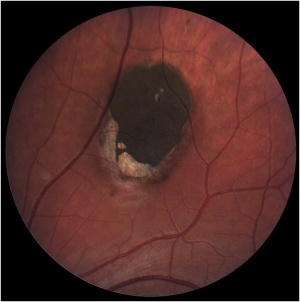

Solitary CHRPE is typically a single, flat, round, hyperpigmented retinal lesion (Image 1). Color may vary from light gray to brown or black, with smooth or scalloped margins. There is typically a sharp demarcation between CHRPE and adjacent normal RPE, with a normal appearance of the overlying retina and vasculature. Lesions are generally located equatorially, with a predominance in the superotemporal quadrant, but may be located throughout the fundus.[10] Macular involvement is rare. Size varies from 100 μm to several disc diameters.[10] The lesion may be surrounded by a marginal depigmented halo or contain multiple hypopigmented lacunae. These hypopigmented areas show a tendency to enlarge slowly over time.[7][14]

Grouped (Multifocal)

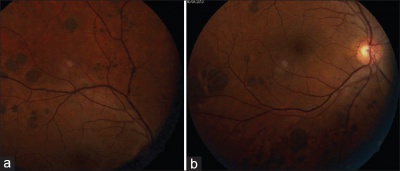

Multiple lesions arranged in a cluster constitute grouped CHRPE (Image 2). Each cluster might include up to 30 lesions, which may vary from 100–300 μm in size, and is usually confined to one sector or quadrant of the fundus.[10] Lesions tend to increase in size towards the fundus periphery, lack haloes and lacunae, and are often termed “bear tracks” due to their resemblance to animal footprints.[10]

Atypical

Congenital hypertrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium lesions associated with FAP are typically smaller in diameter (50–100 μm) than solitary lesions.[10] Clinically, they appear as multiple oval-, spindle-, comma-, or fishtail-shaped lesions haphazardly distributed across the fundus (Image 3). Retinal invasion and proliferation of RPE, capillaries, and glial cells are typical.[10] Larger lesions may contain depigmented lacunae and can be surrounded by depigmented haloes, mottled RPE, and small, pigmented satellite lesions.[10][15] Bilateral lesions occur in 78% of patients.[15] If these lesions are seen in a family member with FAP pedigree, it is almost certainly associated with malignant adenomatous polyposis.[16]

Diagnostic procedures

The diagnosis of CHRPE is usually made clinically, and no additional diagnostic procedures are generally necessary. Color fundus photography is useful for documentation and follow-up of lesions, and widefield scanning-laser ophthalmoscopy has been recommended as a screening tool.[17] Ancillary testing may be beneficial in uncertain cases.

Typical diagnostic findings include:

- Fundus autofluorescence: Lesions typically demonstrate hypoautofluorescence due to their high melanin content. Non-pigmented halos or lacunae may show autofluorescence.[18]

- Fluorescein angiography (FA) or indocyanine green angiography (ICGA): No leakage is demonstrated. Lesions typically block underlying choroidal fluorescence, except in areas of depigmented lacunae or haloes.[10]

- Optical coherence tomography: Findings include retinal thinning and photoreceptor loss over lesions, with absence of RPE and increased transmission of light in areas of lacunae.[19]

- Optical coherence tomography angiography (OCT-A): Limitations exist for the evaluation of CHRPE with OCT-A due to thickened RPE and increased cumulative melanin granules. However, this modality is better than FA or ICGA in visualizing choroidal vasculature.[20]

- Electroretinogram, electrooculogram, and A-scan and B-scan ultrasonography are non-contributory.[10]

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnoses include choroidal melanoma, choroidal nevus, melanocytoma, focal pigmentation (caused by injury, inflammation, or drug toxicity), true hyperplasia of the RPE, and black sunburst lesions in sickle cell retinopathy. Congenital grouped albinotic retinal pigment epithelial spots (CGARPES) or "polar bear tracks" may resemble grouped CHRPE but are characterized by multiple grouped, white, variably sized, albinotic spots of the RPE.[21] The nature of these lesions has not been investigated histologically.

Management

Screening

Congenital hypertrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium is a non-invasive, rapid, early phenotypical screening marker of FAP. Clinical recognition further allows increased gene analysis efficiency, even though the absence of CHRPE alone cannot exclude FAP.[22]

Medical therapy

No active intervention is generally indicated or required. Proton beam therapy has been described for rare complicated cases.[23]

Complications

Lesions associated with CHRPE have been documented to enlarge in 46–83% of cases over at least 3 years of follow-up.[10] There have been reports on foveal extension of CHRPE lesions, which may result in impaired visual acuity.[24] Rarely, nodular pigmented adenocarcinomas may arise from within areas of CHRPE, with untreated nodular lesions having been documented to progress to pedunculated tumors with associated serous retinal detachment.[25][26] Premacular gliosis and cystoid macular edema are frequently seen when peripheral pigmented or non-pigmented RPE tumors arise within CHRPE.[27] Congenital hypertrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium may occasionally be complicated by choroidal neovascularization.[28]

Additional Resources

References

- ↑ Coleman P, Barnard N. Congenital hypertrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium: prevalence and ocular features in the optometric population. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2007;27:547–555.

- ↑ Wallis YL et al: Genotype-phenotype correlation between position of constitutional APC gene mutation and CHRPE expressed in FAP. Hum Gene. 1994;94:543-548.

- ↑ Traboulsi ET et al. Pigmented ocular fundus lesions and APC mutations in familial adenomatous polyposis. Ophth Genet. 1996;17:167-174.

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 Deibert B, Ferris L, Sanchez N, Weishaar P. The link between colon cancer and congenital hypertrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium (CHRPE). Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep. 2019 Sep;15:100524.

- ↑ Nieuwenhuis MH, Vasen HF. Correlations between mutation site in APC and phenotype of familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP): a review of the literature. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2007;61:153-161.

- ↑ Caspari R et al. Familial adenomatous polyposis: desmoid tumours and lack of ophthalmic lesions (CHRPE) associated with APC mutations beyond codon 1444. Hum Mol Genet. 1995;4:337-340.

- ↑ Jump up to: 7.0 7.1 7.2 Buettner H. Congenital hypertrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium. Am J Ophthalmol. 1975;79:177–189.

- ↑ Lloyd WC III et al. Congenital hypertrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium: electron microscopic and morphometric observations. Ophthalmology. 1990;97:1052–1060.

- ↑ Kasner L et al. A histopathologic study of the pigmented fundus lesions in familial adenomatous polyposis. Retina. 1992;12:35-42.

- ↑ Jump up to: 10.00 10.01 10.02 10.03 10.04 10.05 10.06 10.07 10.08 10.09 10.10 10.11 Meyer CH, Gerding H. Congenital Hypertrophy of the Retinal Pigment Epithelium. In: Ryan SJ (ed.). Retina. 5th edition. Elsevier; 2013. 2209-2213.

- ↑ Buettner H. Congenital hypertrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium in familial polyposis coli. Int Ophthalmol. 1987;10:109–110.

- ↑ Traboulsi EI et al. A clinicopathologic study of the eyes in familial adenomatous polyposis with extracolonic manifestations (Gardner's syndrome). Am J Ophthalmol. 1990;110:550–561.

- ↑ Mishra A, Aggarwal S, Shah S, Negi P. An interesting case of "bear track dystrophy". Egypt Retina J. 2014;2:114-117.

- ↑ Shields CL et al. Solitary congenital hypertrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium. Clinical features and frequency of enlargement in 330 patients. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:1968–1976.

- ↑ Jump up to: 15.0 15.1 Traboulsi EI et al. Prevalence and importance of pigmented ocular fundus lesions in Gardner’s syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:661–667.

- ↑ Rushwurm I et al. Ophthalmic and genetic screening in pedigrees with familial adenomatous polyposis. Am J Ophthalmol.1998;125:680-686.

- ↑ Meyer CH, Holz FG. Documentation of congenital hypertrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium with wide-field funduscopy. Semin Ophthalmol. 2009;24:251-3.

- ↑ Shields CL et al. Autofluorescence of congenital hypertrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium. Retina. 2007;27:1097-1111.

- ↑ Shields CL et al. Photoreceptor loss overlying congenital hypertrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium by optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:661-665.

- ↑ Shanmugam PM et al. Ocular coherence tomography angiography features of congenital hypertrophy of retinal pigment epithelium. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2019;67(4):563-566.

- ↑ Arana LA et al. Familial Congenital Grouped Albinotic Retinal Pigment Epithelial Spots. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128(10):1362–1364.

- ↑ Bonnet LA et al. Congenital Hypertrophy of the Retinal Pigment Epithelium (CHRPE) as a Screening Marker for Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (FAP): Systematic Literature Review and Screening Recommendations. Clin Ophthalmol. 2022 Mar 15;16:765-774. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S354761. PMID: 35321042; PMCID: PMC8934868.

- ↑ Moulin AP et al. RPE adenocarcinoma arising from a congenital hypertrophy of the RPE (CHRPE) treated with proton therapy. Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd. 2014;231:411-413.

- ↑ Van der Toren K, Luyten GP. Progression of papillomacular congenital hypertrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium associated with impaired visual function. Arch Ophthalmol. 1998;116:256–257.

- ↑ Shields JA et al. Malignant transformation of congenital hypertrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:2213–2216.

- ↑ Trichopoulos N et al. Adenocarcinoma arising from congenital hypertrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2006;244:125–128.

- ↑ Shields JA et al. Adenocarcinoma Arising From Congenital Hypertrophy of Retinal Pigment Epithelium. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119(4):597–602. doi:10.1001/archopht.119.4.597

- ↑ Bellamy JP, Cohen SY. Congenital Hypertrophy of the Retinal Pigment Epithelium Complicated by Choroidal Neovascularization. Ophthalmol Retina; 2022 Jun;6(6):511. doi: 10.1016/j.oret.2022.02.005.