Terson Syndrome

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Terson syndrome is recognized by the following codes as per the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) 10 nomenclature, as classified by its location of hemorrhage:

- H43.10 Vitreous hemorrhage, unspecified eye

- H43.11 Vitreous hemorrhage, right eye

- H43.12 Vitreous hemorrhage, left eye

- H43.13 Vitreous hemorrhage, bilateral

Disease

Terson syndrome is characterized by intraocular hemorrhage associated with subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH), intracerebral hemorrhage, or traumatic brain injury. Intraocular hemorrhage may be present in the vitreous, retina, subretinal space, sub-hyaloid space, or beneath the internal limiting membrane.

History

In 1881, German ophthalmologist Moritz Litten first characterized vitreous hemorrhage (VH) associated with SAH [2][3]. In 1990, the French ophthalmologist Albert Terson reported VH associated with intracranial hemorrhage, resulting in the term Terson syndrome [2][3].

Epidemiology

Terson syndrome has been reported in 8-19.3% of SAH [4][5][6][7][2], 9.1% of intracerebral hemorrhages, and 3.1% of traumatic brain injury [2]. Of vitreous hemorrhages not caused by diabetes or direct trauma, 5.5% are attributed to Terson syndrome [8].

Terson syndrome usually occurs in adults, but has been reported in children as young as 7 months [9][10]. It can be unilateral or bilateral [11].

Relationship to neurologic outcomes

Low Glasgow coma scale, high Hunt and Hesse grade, and high Fisher grade are associated with a higher incidence of Terson syndrome [2].

Neurological outcomes and mortality rate are worse in patients with SAH and Terson syndrome than patients with SAH alone [2] [12] [13][14][15][16]. In a study by Pfausler in patients with SAH, mortality was 90% when Terson syndrome was present, and 10% when absent [13]. In a study by Gutierrez Diaz, mortality was 50% when Terson syndrome was present, and 20% when absent [17].

Pathogenesis

The mechanism for Terson syndrome is not fully known. The most widely held theory is that the rise in intracranial pressure increases both arterial and venous pressure while causing CSF to efflux into the optic nerve sheath [19]. The increased pressure wave in the retrobulbar optic nerve sheath mechanically compresses the central retinal vein and increases venous hypertension, resulting in rupture of thin optic nerve and retinal capillaries [20][21].

Other theories included hemorrhagic CSF directly being transmitted through the optic nerve sheath [22] or around perivascular spaces [23]. However, this are not supported anatomically by the absence of a known channel between these spaces [24] and by patients with confirmed Terson syndrome without intracerebral hemorrhage. In addition, fluorescein angiography demonstrates leakage at the disc margin in patients with Terson syndrome with vitreous hemorrhage [25]. This suggests rupture of blood vessels as opposed to transfer of hemorrhage through the optic nerve.

More recently, some researchers have proposed a glymphatic conduit as a possible way for blood to efflux from the cerebral space to the retina [26].

Etiology

Terson syndrome has been associated with multiple conditions that sustain a spike in intracranial pressure. Most common causes include trauma causing subarachnoid hemorrhage, intracerebral hemorrhage, traumatic brain injury, subdural hematoma. Less common causes include carotid artery occlusion, cortical venous sinus thrombosis [27], lumbosacral myelomeningocele, moyamoya disease [28][29], epidural injection [30], intra-arterial angiography, or iatrogenic bleeding during endoscopic third ventriculostomy [31].

Relationship to aneurysm site

Although some studies have shown a higher rate of Terson syndrome with anterior circulation or anterior communicating artery aneurysms [12] [32][33], many other studies have found no correlation between aneurysm location and Terson syndrome [2][34][35][36][12][37] . There is no apparent relationship between the location of the intracranial bleeding and the laterality of Terson syndrome [38][36][11][13].

Diagnosis

Clinical Presentation

Intraocular hemorrhage most often occurs within the first 1-24 hours of intracranial bleeding[15][14], but delayed intraocular hemorrhage has been noted up to 2 weeks [2] or even 47 days [25]. In addition, intraocular hemorrhage can be seen prior to presentation with subarachnoid hemorrhage [33].

Diagnosis is often delayed due to the inability to dilate the pupils due to the need for neurologic monitoring. Patients may also have cognitive impairment that prevents them from verbalizing visual complaints or complying with visual testing . Median time from visual symptoms to referral to an ophthalmologist was 5.2 months for unilateral cases and 4.9 months for bilateral cases (in a series of 17 patients with Terson syndrome) [40].

Physical Examination

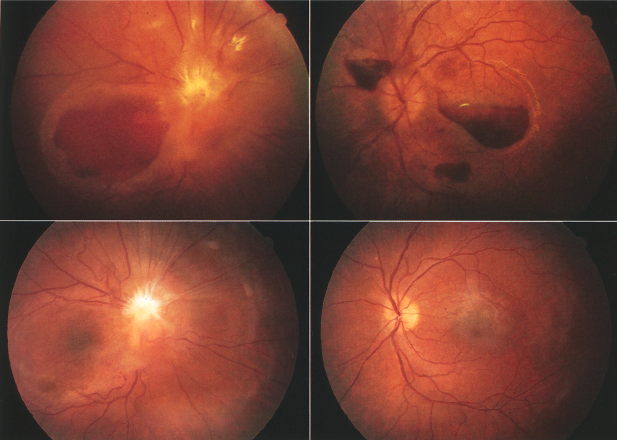

Funduscopic exam is the gold standard for diagnosis of Terson syndrome. Terson syndrome often presents with dome-shaped hemorrhages in the macula [41]. A macular “double ring” sign may be seen with the inner ring caused sub-ILM hemorrhage and the outer ring caused by sub-hyaloid hemorrhage [42].

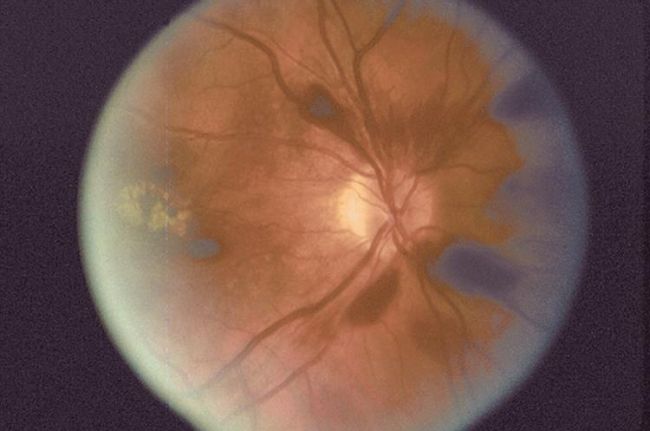

Loss of red reflex is seen in 20% of eyes with Terson syndrome[2]. B-scan may be used to confirm vitreous hemorrhage when no view to the fundus is present (Fig. 4). Orbital CT scan may detect Terson syndrome in two-thirds of cases, showing retinal crescentic hyperdensities and retinal nodularity [43][28].

Complications

Multiple complications have been reported after Terson syndrome. Epiretinal membrane is the most common sequelae of Terson syndrome, with an incidence of 15-78% [45][46][47][48][11]. This is thought to be caused by blood inducing glial proliferation and disruption of the ILM [45][49][46].

Retinal/perimacular folds occur in 20% of patients with Terson syndrome, retinal detachment occurs in 9%, and ghost cell glaucoma occurs in ~4% [45][50][40]. Proliferative vitreoretinopathy and preretinal fibrosis have also been reported after Terson syndrome [51][52][28][53]. There have been two reported patients with macular holes found intraoperatively during pars plana vitrectomy for vitreous hemorrhage [46]. Dissociated optic nerve fiber layer appearance (DONFL) may be noted after removal of ILM in Terson syndrome with sub-ILM hemorrhage [54].

Management

Treatment and prognosis

Intraocular hemorrhage frequently resolves spontaneously [10], but persists past 19 months in approximately 50% of patients. Vision loss is usually reversible but can be permanent [10][56].

Observation is appropriate for patients with improving or small hemorrhage, poor visual potential, only 1 eye affected, no risk of amblyopia, or if there are comorbid conditions that make anesthesia high risk [2][53][47]. Recommendations include elevation of the head, avoiding strenuous activity, and avoiding blood thinners or NSAID’s as able. Complications of observation include epiretinal membrane formation, retinal detachment, macular holes, retinal folds, or proliferative vitreoretinopathy [13][48][46][52][50]

Vitreous hemorrhage should not be observed for more than 3 months without considering pars plana vitrectomy [2][32][49]. This is supported by a study of 36 eyes with Terson syndrome in which eyes that were operated on within 90 days of occurrence of VH had better final VA than eyes that were operated on after 90 days [53]. However, there is no consensus on optimal timing for vitrectomy in Terson syndrome.

Multiple studies have shown good outcomes after pars plana vitectomy. In a study of 7 eyes of 6 patients that underwent pars plana vitrectomy for Terson syndrome, median VA went from HM to 20/25 and no complications were observed [2]. In another study on PPV for Terson syndrome, 96% of patients had rapid visual improvement and 81% had better than 20/30 vision [57]. In a series of 15 eyes that underwent PPV for VH, 93% had final VA of 20/40 or better. [45]. ILM peeling has also been described in the surgical management of Terson syndrome [58].

Younger patients (<45 years old) who undergo PPV for Terson syndrome have better final visual acuity than older patients (>45 years old)[53]. Studies have shown no difference in final visual acuity between patients who were conservatively managed and those who underwent PPV. However, visual recovery was more rapid in the vitrectomy group despite these patients having denser vitreous hemorrhage [47]. Intravitreal TPA and gas have been used for recalcitrant Terson syndrome[59] [10]. Premacular subhyaloid hemorrhage may also treated with Nd-YAG to puncture the posterior hyaloid face to allow drainage of blood into the vitreous [60].

References

- ↑ AAO One Network Images. one.aao.org/images/terson-syndrome

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 Czorlich P, Skevas C, Knospe V, et al. Terson syndrome in subarachnoid hemorrhage, intracerebral hemorrhage, and traumatic brain injury. Neurosurg Rev. Epub 2014 Aug 31.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Skevas C, Czorlich P,Knospe V, et al. Terson's syndrome--rate and surgical approach in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage: a prospective interdisciplinary study. Ophthalmology. 2014 Aug;121(8):1628-33.

- ↑ Iuliano L, Fogliato G, Codenotti M. Intrasurgical imaging of subinternal limiting membrane blood diffusion in terson syndrome. Case Rep Ophthalmol Med. 2014;2014:689793.

- ↑ Michalewska Z, Michalewski J, Nawrocki J. Possible methods of blood entrance in Terson syndrome. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. 2010 Nov-Dec;41 Suppl:S42-9.

- ↑ Morris R., Kuhn F., and Witherspoon C.D.: Hemorrhagic macular cysts. Ophthalmology 1994; 101: 1.

- ↑ Morris R., Kuhn F., Witherspoon C.D., et al: Hemorrhagic macular cysts in Terson's syndrome and its implications for macular surgery. Dev Ophthalmol 1997; 29: pp. 44-54.

- ↑ Verbraeken H, Van Egmond J. Non-diabetic and non-oculotraumatic vitreous haemorrhage treated by pars plana vitrectomy. Bull Soc Belge Ophtalmol. 1999;272:83-9.

- ↑ Bhardwaj G., Jacobs M.B., Moran K.T., and Tan K.: Terson syndrome with ipsilateral severe hemorrhagic retinopathy in a 7-month-old child. J AAPOS 2010; 14: pp. 441-443.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Kapoor S. Terson syndrome: an often overlooked complication of subarachnoid hemorrhage. World Neurosurg. 2014 Jan;81(1):e4.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Ritland JS, Syrdalen P, Eide N, Vatne HO, Øvergaard R. Outcome of vitrectomy in patients with Terson syndrome. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2002 Apr;80(2):172-5.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Fountas KN, Kapsalaki EZ, Lee GP, et al. Terson hemorrhage in patients suffering aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: predisposing factors and prognostic significance. J Neurosurg. 2008 Sep;109(3):439-44.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Pfausler B, Belcl R, Metzler R, Mohsenipour I, Schmutzhard E. Terson's syndrome in spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage: a prospective study in 60 consecutive patients. J Neurosurg. 1996 Sep;85(3):392-4.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Stienen MN, Lücke S, Gautschi OP, Harders A. Terson haemorrhage in patients suffering aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage: a prospective analysis of 60 consecutive patients. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2012 Jul;114(6):535-8.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Manschot WA. Subarachnoid hemorrhage. Intraocular symptoms and their pathogenesis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1954;38:501-505.

- ↑ Shaw HE Jr & Landers MB III (1975): Vitreous hemorrhage after intracranial hemorrhage. Am J Ophthalmol 80: 207–213.

- ↑ Gutierrez Diaz A, Jimenez Carmena J, Ruano Martin F, Diaz Lopez P, Muñoz Casado MJ. Intraocular hemorrhage in sudden increased intracranial pressure (Terson syndrome). Ophthalmologica. 1979;179(3):173-6.

- ↑ Ogawa T, Kitaoka T, Dake Y, Amemiya T. Terson syndrome: a case report suggesting the mechanism of vitreous hemorrhage. Ophthalmology. 2001 Sep;108(9):1654-6.

- ↑ Manschot, W. A. "Subarachnoid hemorrhage: intraocular symptoms and their pathogenesis." American Journal of Ophthalmology 38.4 (1954): 501-505.

- ↑ Hayreh, Sohan S. "Pathogenesis of Terson syndrome." Indian Journal of Ophthalmology 70.12 (2022): 4130-4137.

- ↑ Gress DR, Wintermark M, Gean AD. A case of Terson syndrome and its mechanism of bleeding. J Neuroradiol. 2013 Oct;40(4):312-4.

- ↑ FH, DOUBLER. "A case of hemorrhage into the optic nerve sheath as a direct extension from a diffuse intra-meningeal hemorrhage caused by rupture of an aneurysm of a cerebral artery." Arch Ophthalmol 46 (1917): 533-536.

- ↑ Sakamoto, Masashi, et al. "Magnetic resonance imaging findings of Terson’s syndrome suggesting a possible vitreous hemorrhage mechanism." Japanese journal of ophthalmology 54 (2010): 135-139.

- ↑ Anderson, Douglas R. "Ultrastructure of the optic nerve head." Archives of Ophthalmology 83.1 (1970): 63-73.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Ogawa T, Kitaoka T, Dake Y, Amemiya T. Terson syndrome: a case report suggesting the mechanism of vitreous hemorrhage. Ophthalmology. 2001 Sep;108(9):1654-6.

- ↑ Kumaria, Ashwin, et al. "An explanation for Terson syndrome at last: the glymphatic reflux theory." Journal of Neurology 269.3 (2022): 1264-1271.

- ↑ Takkar A, Kesav P, Lal V, Gupta A. Teaching NeuroImages: Terson syndrome in cortical venous sinus thrombosis. Neurology. 2013 Aug 6;81(6):e40-1.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Kim HS, Lee SW, Sung SK, Seo EK. Terson syndrome caused by intraventricular hemorrhage associated with moyamoya disease. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2012 Jun;51(6):367-9.

- ↑ Arakawa Y, Goto Y, Ishii A, Ueno Y, Kikuta K, Yoshizumi H, Katsuta H, Kenmochi S, Yamagata S. Terson syndrome caused by ventricular hemorrhage associated with moyamoya disease--case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2000 Sep;40(9):480-3.

- ↑ Naseri A, Blumenkranz MS, Horton JC. Terson's syndrome following epidural saline injection. Neurology. 2001 Jul 24;57(2):364.

- ↑ Hoving EW, Rahmani M, Los LI, Renardel de Lavalette VW. Bilateral retinal hemorrhage after endoscopic third ventriculostomy: iatrogenic Terson syndrome. J Neurosurg. 2009 May;110(5):858-60.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Fahmy JA. Vitreous haemorrhage in subarachnoid haemorrhage--Terson's syndrome. Report of a case with macular degeneration as a complication. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh). 1972;50(2):137-43.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Garfinkle AM, Danys IR, Nicolle DA, Colohan AR, Brem S. Terson's syndrome: a reversible cause of blindness following subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 1992 May;76(5):766-71.

- ↑ Stienen, Martin N., et al. "Terson haemorrhage in patients suffering aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage: a prospective analysis of 60 consecutive patients." Clinical neurology and neurosurgery 114.6 (2012): 535-538.

- ↑ Kang, Hae Min, et al. "Clinical characteristics of asymptomatic Terson syndrome in the patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage." International Journal of Ophthalmology 13.2 (2020): 292.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Czorlich, Patrick, et al. "Terson’s syndrome–Pathophysiologic considerations of an underestimated concomitant disease in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage." Journal of Clinical Neuroscience 33 (2016): 182-186.

- ↑ Wu, Li Na, et al. "Incidence of Terson’s syndrome in patients with SAH in a Chinese hospital." Current Eye Research 38.1 (2013): 97-101.

- ↑ Stienen, Martin N., et al. "Terson haemorrhage in patients suffering aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage: a prospective analysis of 60 consecutive patients." Clinical neurology and neurosurgery 114.6 (2012): 535-538.

- ↑ AAO One Network Images. one.aao.org/images/preretinal-hemorrhage-2

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Gnanaraj L, Tyagi AK, Cottrell DG, Fetherston TJ, Richardson J, Stannard KP, Inglesby DV. Referral delay and ocular surgical outcome in Terson syndrome. Retina. 2000;20(4):374-7.

- ↑ Friedman S.M., and Margo C.E. Bilateral subinternal limiting membrane hemorrhage with Terson syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 1997; 124: pp. 850-851.

- ↑ Srinivasan S, Kyle G. Subinternal limiting membrane and subhyaloid haemorrhage in Terson syndrome: the macular 'double ring' sign. Eye (Lond). 2006 Sep;20(9):1099-101.

- ↑ Swallow CE, Tsuruda JS, Digre KB, Glaser MJ, Davidson HC, Harnsberger HR. Terson syndrome: CT evaluation in 12 patients. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1998 Apr;19(4):743-7.

- ↑ https://www.aao.org/education/annual-meeting-video/sub-ilm-fibrosis-excision-in-pediatric-terson-synd

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 45.3 Sharma T, Gopal L, Biswas J, Shanmugam MP, Bhende PS, Agrawal R, Shetty NS, Sanduja N. Results of vitrectomy in Terson syndrome. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers. 2002 May-Jun;33(3):195-9.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 46.2 46.3 Rubowitz A, Desai U. Nontraumatic macular holes associated with Terson syndrome. Retina. 2006 Feb;26(2):230-2.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 Schultz PN, Sobol WM, Weingeist TA. Long-term visual outcome in Terson syndrome. Ophthalmology. 1991 Dec;98(12):1814-9.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Yokoi M, Kase M, Hyodo T, Horimoto M, Kitagawa F, Nagata R. Epiretinal membrane formation in Terson syndrome. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 1997 May-Jun;41(3):168-73.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Augsten R, Königsdörffer E, Strobel J. Surgical approach in terson syndrome: vitreous and retinal findings. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2000 Oct-Dec;10(4):293-6.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Keithahn M.A., Bennett S.R., Cameron D., and Mieler W.F.: Retinal folds in Terson syndrome. Ophthalmology 1993; 100: pp. 1187-1190.

- ↑ Mena O.J., Paul I., and Reichard R.R.: Ocular findings in raised intracranial pressure: a case of Terson syndrome in a 7-month-old infant. Am J Forensic Med Pathol 2011; 32: pp. 55-57.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Velikay M., Datlinger P., Stolba U., Wedrich A., Binder S., and Hausmann N.: Retinal detachment with severe proliferative vitreoretinopathy in Terson syndrome. Ophthalmology 1994; 101: pp. 35-37.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 53.2 53.3 Garweg JG, Koerner F. Outcome indicators for vitrectomy in Terson syndrome. Acta Ophthalmol. 2009 Mar;87(2):222-6.

- ↑ Tripathy K. Dissociated optic nerve fiber layer in a case of Terson syndrome [published online ahead of print, 2019 Jun 3]. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2019;1120672119853465. doi:10.1177/1120672119853465

- ↑ Schultz PN, Sobol WM, Weingeist TA. Long-term visual outcome in Terson syndrome. Ophthalmology. 1991 Dec;98(12):1814-9.

- ↑ Roux F.X., Panthier J.N., Tanghe Y.M., Gallina P., Oswald A.M., Mérienne L., and Cioloca C.: Terson's syndrome and intraocular complications in meningeal hemorrhages (26 cases) [in French]. Neurochirurgie 1991; 37: pp. 6-11.

- ↑ Kuhn F, Morris R, Witherspoon CD, Mester V. Terson syndrome. Results of vitrectomy and the significance of vitreous hemorrhage in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage. Ophthalmology. 1998 Mar;105(3):472-7.

- ↑ Abdelkader E, Lois N. Internal limiting membrane peeling in vitreo-retinal surgery. Surv Ophthalmol. 2008 Jul-Aug;53(4):368-96.

- ↑ Serracarbassa P.D., Rodrigues L.D., and Rodrigues J.R.: Tissue plasminogen activator and intravitreal gas for the treatment of Terson's syndrome: case report. Arq Bras Oftalmol 2009; 72: pp. 403-405.

- ↑ Ulbig MW, Mangouritsas G, Rothbacher HH, Hamilton AM, McHugh JD. Long-term results after drainage of premacular subhyaloid hemorrhage into the vitreous with a pulsed Nd:YAG laser. Arch Ophthalmol. 1998 Nov;116(11):1465-9.