Punctal Atresia

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Punctal Atresia or Punctal Agenesis (PA) is the absence of the lacrimal punctum[1]. PA most commonly occurs due to failed development during embryogenesis. Unlike mere veils, significant punctal agenesis is often accompanied by extensive atresia of both the horizontal and vertical canaliculi[2].

Embryology

Canalization of the lacrimal system ectoderm begins at 12 weeks and progresses laterally until the seventh month[3], when the puncta open up at the top of the lid margin[4]. Canalization begins at the lacrimal sac and progresses proximally toward the canaliculi and distally toward the nose[5]. The development of the puncta and canalicular wall is closely linked with the development of first and second branchial arches in the nasomaxillary region. Thus, any disruption in craniofacial development, particularly in the nasomaxillary region, is associated with the dysgenesis of lacrimal tissues and other ocular deficits[6][7][8]. This anomaly is exceedingly rare, with few reports described in the literature.

Etiology

- Sporadic: The most common etiology of this condition; can occur as both isolated or as an association with ocular and/or systemic syndromes[6][8][9].

- Inherited: Autosomal dominant inheritance with variable expressivity and penetrance has been reported[10].

Clinical Presentation

- Symptoms: The most common clinical presentation is epiphora, other symptoms including ocular discharge (more common in proximal punctal involvement rather than both upper and lower punctum and canaliculi agenesis), redness, and pain (especially in context of dacryocystitis or dacryocele). In eyes with no puncta, there may be occasional watering or no watering.

- Diagnosis:

- PA is a clinical diagnosis that requires thorough history and careful examination.

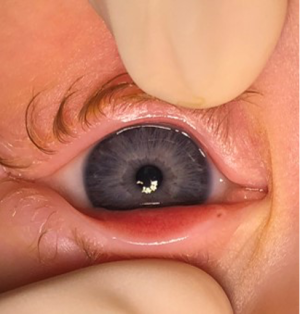

- Slit lamp exam will show absence of the punctal papilla and dimple expected in the area of the punctum. Occasionally, eyelashes may be found medially to expected punctal location[11].

- PA must be distinguished from punctal stenosis and its secondary causes, including infection, trauma, inflammation, neoplasms, and medication effects. This can be done with a thorough history and review of medications.

- Difficult diagnoses can utilize dacryocystography to visualize anatomic details of lacrimal drainage system[12].

- PA Complications: dacryocystitis, dacryocele, lacrimal fistula, lacrimal mucocele

- Associated Ocular Findings: Absence of the caruncle, nasolacrimal duct obstruction, canliculops, eyelid skin tags, distichiasis, divergent strabismus, refractive disorders, ptosis, entropion, blepharitis, epicanthus, amblyopia, nystagmus [1][10][13][14].

Differential Diagnosis

Punctal stenosis, nasolacrimal duct obstruction, epiphora due to dry eye, secondary canicular obstruction to inflammation, infection, trauma, drugs, or systemic disease

Management

Medical:

Patients with PA complications (including dacryocystitis, dacryocele, and mucocele) may need treatment with oral empiric antibiotics with gram positive coverage. Warm compresses and massages may help decompress dacryocystoceles. Worsening complications with oral antibiotics or signs of progression to orbital cellulitis may need culture-tailored antibiotics or even IV antibiotics. Asymptomatic patients, with no epiphora or infection, can be observed

Surgical:

Definitive treatment of PA often requires surgery. Surgery type depends on extent of PA and concurrent obstruction. The strategy for surgical treatment of symptomatic PA is often tailored to each case and is strongly tied to the underlying anatomy[2].

- PA with normal underlying canicular system: Membrane lysis with a punctal dilator can create a direct passage to the underlying intact canicular system [12][15]. However, PA with a normal underlying canicular system is uncommon.

- PA with concurrent proximal obstruction: Canalicular marsupialization and Jones (Pyrex glass) tube placement can be performed to create a neo-punctum and relieve obstruction. The conjunctiva is opened in the punctal region and blunt dissection is used to identify the blind end of the canaliculus. This blind end is then opened with a punctal dilater to create an open canaliculus. The surrounding tissue of the open canaliculus is trimmed to create a new punctum [16].

- PA with significant canalicular obstruction/stenosis: Canalicular trephination may be considered to recanalize the canaliculus with a lacrimal stent. Stent placement often occurs for 6-12 months to prevent contracture and also serve as scaffolding for epithelialization. Mini-Monoka stents have been reported to have higher success rates than standard silicone tubing due to their mono-canalicular design that is self-retaining with a nonirritant collarette[17][18].

- PA with insufficient canalicular tissue: Conjunctivodacryocystorhinostomy (CDCR) with Jones tube placement is often the standard of treatment for patients with insufficient canalicular tissue. The Jones tube is placed in an opening created at the inferior half of the caruncle and threaded through into the middle nasal meatus[19].

Association with Systemic Disease

PA can occur in isolation or as part of an underlying genetic syndrome, most commonly ectodermal dysplasias[9][10][20]. As PA has been associated with a variety of genetic syndromes, this ocular finding has been proposed to be an ophthalmologic marker of potential underlying syndromes[6].

Syndromes associated with PA in the literature include:

| CollapseEctodermal dysplasias: |

| Aplasia of Lacrimal and Major Salivary Glands Syndrome[27][28] |

| Down’s syndrome [6][29][30] |

| Lacrimo-Auriculo-Dento-Digital Syndrome[31][32] |

| Cornelia de Lange syndrome[6][8][33] |

| Treacher-Collins[6][34] |

| Möbius syndrome[6][35] |

| Branchio-oto-renal syndrome[6] |

| 22q11.2 deletion syndrome[6] |

| 1q21.1 microdeletion syndrome[6] |

| Neurofibromatosis I[6][36] |

| CHARGE syndrome[37] |

| Apert Syndrome[38] |

| Congenital Arhinia-Microphthalmia Syndrome[39][40] |

| Johanson-Blizzard Syndrome[41][42] |

| Pashayan Syndrome[43][44][45] |

References

Add text here

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 Lyons, C.J., P.M. Rosser, and R.A. Welham, The management of punctal agenesis. Ophthalmology, 1993. 100(12): p. 1851-5.

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 Dohlman, J.C., L.A. Habib, and S.K. Freitag, Punctal agenesis: Embryology, presentation, management modalities and outcomes. Ann Anat, 2019. 224: p. 113-116.

- ↑ de la Cuadra-Blanco, C., et al., Morphogenesis of the human excretory lacrimal system. J Anat, 2006. 209(2): p. 127-35.

- ↑ Low, J.E., M.A. Johnson, and J.A. Katowitz, Management of Pediatric Upper System Problems: Punctal and Canalicular Surgery, in Pediatric Oculoplastic Surgery, J.A. Katowitz, Editor. 2002, Springer New York: New York, NY. p. 337-346.

- ↑ Moscato, E.E., J.P. Kelly, and A. Weiss, Developmental anatomy of the nasolacrimal duct: implications for congenital obstruction. Ophthalmology, 2010. 117(12): p. 2430-4.

- ↑ Jump up to: 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 6.12 Landau-Prat, D., et al., Punctal Atresia As a Clinical Indicator of Systemic Genetic Anomalies. Semin Ophthalmol, 2024: p. 1-4.

- ↑ Ali, M.J. and M.N. Naik, Canalicular wall dysgenesis: the clinical profile of canalicular hypoplasia and aplasia, associated systemic and lacrimal anomalies, and clinical implications. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg, 2013. 29(6): p. 464-8.

- ↑ Jump up to: 8.0 8.1 8.2 Ali, M.J. and F. Paulsen, Syndromic and Nonsyndromic Systemic Associations of Congenital Lacrimal Drainage Anomalies: A Major Review. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg, 2017. 33(6): p. 399-407.

- ↑ Jump up to: 9.0 9.1 Kaercher, T., Ocular symptoms and signs in patients with ectodermal dysplasia syndromes. Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology, 2004. 242(6): p. 495-500.

- ↑ Jump up to: 10.0 10.1 10.2 Ali, M.J., Punctal Agenesis, in Atlas of Lacrimal Drainage Disorders, M.J. Ali, Editor. 2018, Springer Singapore: Singapore. p. 197-200.

- ↑ Ali MJ, K.H.E.o.t.l.d.s.I.A.M., editor. In: Principles and Practice of Lacrimal Surgery. New Delhi, India: Springer; 2015. pp. 9–15.

- ↑ Jump up to: 12.0 12.1 Yuen, S.J., C. Oley, and T.J. Sullivan, Lacrimal outflow dysgenesis. Ophthalmology, 2004. 111(9): p. 1782-90.

- ↑ Javed Ali, M., et al., Canaliculops Associated With Punctal Agenesis: A Clinicopathological Correlation and Review of Literature. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg, 2015. 31(4): p. e108-11.

- ↑ Han, B.L. and H.S. Shin, Dacryocystocele with congenital unilateral lacrimal puncta agenesis in an adults. J Craniofac Surg, 2013. 24(4): p. 1242-3.

- ↑ Ong, C.A., et al., Bilateral lacrimal sac mucocele with punctal and canalicular atresia. Med J Malaysia, 2005. 60(5): p. 660-2.

- ↑ Katowitz, J.A., Silicone Tubing in Canalicular Obstructions: A Preliminary Report. Archives of Ophthalmology, 1974. 91(6): p. 459-462.

- ↑ Hussain, R.N., H. Kanani, and T. McMullan, Use of mini-monoka stents for punctal/canalicular stenosis. Br J Ophthalmol, 2012. 96(5): p. 671-3.

- ↑ Zadeng, Z., M. Singh, and U. Singh, Role of Lacrimal Canalicular Trephination and Mini-Monoka Stent in the Management of Idiopathic Distal Canalicular Obstructions: Our Experience of 23 Cases. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila), 2014. 3(1): p. 27-31.

- ↑ Sekhar, G.C., et al., Problems associated with conjunctivodacryocystorhinostomy. Am J Ophthalmol, 1991. 112(5): p. 502-6.

- ↑ Jump up to: 20.0 20.1 Landau Prat, D., et al., Ocular manifestations of ectodermal dysplasia. Orphanet J Rare Dis, 2021. 16(1): p. 197.

- ↑ Elmann, S., et al., Ectrodactyly ectodermal dysplasia clefting (EEC) syndrome: a rare cause of congenital lacrimal anomalies. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg, 2015. 31(2): p. e35-7.

- ↑ Käsmann, B. and K.W. Ruprecht, Ocular manifestations in a father and son with EEC syndrome. Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology, 1997. 235(8): p. 512-516.

- ↑ Sutton, V.R., et al., Craniofacial and anthropometric phenotype in ankyloblepharon-ectodermal defects-cleft lip/palate syndrome (Hay-Wells syndrome) in a cohort of 17 patients. Am J Med Genet A, 2009. 149a(9): p. 1916-21.

- ↑ Kantaputra, P.N., C. Pruksachatkunakorn, and P. Vanittanakom, Rapp-Hodgkin syndrome with palmoplantar keratoderma, glossy tongue, congenital absence of lingual frenum and of sublingual caruncles: newly recognized findings. Am J Med Genet, 1998. 79(5): p. 343-6.

- ↑ Allen, R.C., Hereditary disorders affecting the lacrimal system. Curr Opin Ophthalmol, 2014. 25(5): p. 424-31.

- ↑ Zhou, J., et al., Case report: ADULT syndrome: a rare case of congenital lacrimal duct abnormality. Front Genet, 2023. 14: p. 1150613.

- ↑ Neagu, D., et al., Aplasia of the lacrimal and major salivary glands (ALSG). First case report in spanish population and review of the literature. J Clin Exp Dent, 2018. 10(12): p. e1238-e1241.

- ↑ Chapman, D.B., V. Shashi, and D.J. Kirse, Case report: Aplasia of the lacrimal and major salivary glands (ALSG). International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, 2009. 73(6): p. 899-901.

- ↑ Haseeb, A., et al., Down syndrome: a review of ocular manifestations. Ther Adv Ophthalmol, 2022. 14: p. 25158414221101718.

- ↑ Coats, D.K., et al., Nasolacrimal outflow drainage anomalies in Down's syndrome. Ophthalmology, 2003. 110(7): p. 1437-41.

- ↑ Shiang, E.L. and L.B. Holmes, The lacrimo-auriculo-dento-digital syndrome. Pediatrics, 1977. 59(6): p. 927-30.

- ↑ Alhamadi, R., et al., Lacrimo-auriculo-dento-digital syndrome: A case report and literature review. Saudi J Ophthalmol, 2021. 35(2): p. 152-158.

- ↑ Levin, A.V., et al., Ophthalmologic findings in the Cornelia de Lange syndrome. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus, 1990. 27(2): p. 94-102.

- ↑ Wang, F.M., et al., Ocular findings in Treacher Collins syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol, 1990. 110(3): p. 280-6.

- ↑ Aydin, A., et al., [Poland-Möbius syndrome associated with lacrimal punctal and canalicular agenesis]. J Fr Ophtalmol, 2010. 33(2): p. 119.e1-5.

- ↑ Fenton, S. and M.P. Mourits, Isolated conjunctival neurofibromas at the puncta, an unusual cause of epiphora. Eye, 2003. 17(5): p. 665-666.

- ↑ Reeves, M.R., A.M. Nguyen, and B.P. Erickson, Punctal agenesis and delayed-onset dacryocystocele in CHARGE syndrome. J aapos, 2020. 24(6): p. 382-384.

- ↑ Zein, W.M., et al., 174Ocular Manifestations of Syndromes with Craniofacial Abnormalities, in Genetic Diseases of the Eye. 2012, Oxford University Press. p. 0.

- ↑ Thiele, H., et al., Familial arhinia, choanal atresia, and microphthalmia. Am J Med Genet, 1996. 63(1): p. 310-3.

- ↑ Ali, M.J., Bilateral lacrimal mucoceles in a setting of congenital arhinia. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg, 2014. 30(6): p. e167.

- ↑ Almashraki, N., et al., Johanson-Blizzard syndrome. World J Gastroenterol, 2011. 17(37): p. 4247-50.

- ↑ Demir, D., et al., Johanson-Blizzard's Syndrome with a Novel UBR1 Mutation. J Pediatr Genet, 2022. 11(2): p. 147-150.

- ↑ Allanson, J.E., A second family with blepharo-naso-facial syndrome. Clin Dysmorphol, 2002. 11(3): p. 191-4.

- ↑ Putterman, A.M., H. Pashayan, and S. Pruzansky, Eye findings in the blepharo-naso-facial malformation syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol, 1973. 76(5): p. 825-31.

- ↑ Pashayan, H., S. Pruzansky, and A. Putterman, A family with blepharo-naso-facial malformations. Am J Dis Child, 1973. 125(3): p. 389-93.