Dacryocystitis

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Disease

Dacryocystitis is inflammation of the lacrimal sac which typically occurs secondarily to obstruction within the nasolacrimal duct and the resultant backup and stagnation of tears within the lacrimal sac.

Tears are produced by the lacrimal glands, which are paired almond-shaped exocrine glands that sit in the upper lateral portion of each orbit in the lacrimal fossa, an area found within the frontal bone. The tears lubricate the eye and are collected into the superior and inferior puncta, and then drain into the inferior and superior canaliculi. From the canaliculi, the tears pass through the valve of Rosenmüller into the lacrimal sac, where they then flow down the nasolacrimal duct through the valve of Hasner, finally draining into the nasal cavity.[1]

Etiology

Dacryocystitis typically occurs due to a nasolacrimal duct obstruction (NLDO). The condition's etiology can be further categorized by duration of current symptoms (acute versus chronic) and onset (congenital and acquired causes); acute is usually defined as symptoms lasting for <3 months.

Acute dacryocystitis usually requires systemic antibiotic therapy prior to intervention for the NLDO. In the United States, likely bacterial culprits are Staphylococcus aureus, B hemolytic Streptococcus, and Haemophilus influenzae in children, and S epidermidis, S aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa in adults.[2] Chronic dacryocystitis typically presents with fewer inflammatory signs and requires surgical therapy for the underlying cause. It may result from repeated infections and from accumulation of inflammatory debris and or dacryoliths. Wegener granulomatosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and sarcoidosis are several common systemic causes of chronic dacryocystitis.[3]

Congenital and acquired refer to the onset and cause of the NLDO, which guides the treatment algorithm. Congenital forms of dacryocystitis are typically due to obstruction of the valve of Hasner, located in the distal portion of the nasolacrimal duct. If amniotic fluid is not expelled from the nasolacrimal system within a few days following delivery, it can become purulent, leading to neonatal dacryocystitis.[4] Acquired causes of dacryocystitis include involutional changes (aging), systemic disorders (e.g., sarcoidosis), trauma, surgeries (endonasal procedures, maxillectomy), neoplasms, and certain medications.

Epidemiology

Dacryocystitis has a bimodal distribution; most cases occur after birth (congenital dacryocystitis) or in adults aged >40 years (acute dacryocystitis). Congenital NLDO occurs in approximately 6% of newborns and dacryocystitis occurs in 1/3884 live births. In adults, women are more commonly affected than men, and White individuals are more commonly affected than Black individuals.[5] [6]

Risk Factors

The risk factors for dacryocystitis are varied but are almost always related to NLDO.

- Females are at greater risk than males, due to their narrower duct diameter

- Older age leads to narrowing of the punctal openings, slowing tear drainage

- Dacryoliths: a collection of shed epithelial cells, lipids, and amorphous debris within the nasolacrimal system

- Nasal septum deviation, rhinitis, and turbinate hypertrophy

- Damage to the nasolacrimal system due to trauma of the nasoethmoid or maxillary (midfacial) bones

- Endonasal or maxillary procedures (e.g., maxillectomy)

- Neoplasm intrinsic or extrinsic to the nasolacrimal system, causing secondary NLDO

- Systemic diseases such as granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA; formerly Wegener’s granulomatosis), sarcoidosis, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), or lacrimal sac tumors

- Medications such as timolol, dorzolamide, pilocarpine, fluorouracil, docetaxel, idoxuridine, and trifluridine or radioactive iodine

Pathophysiology

Dacryocystitis typically occurs secondary to obstruction of the nasolacrimal duct. Obstruction of the nasolacrimal duct leads to stagnation of tears in a pathologically closed lacrimal drainage system, with the stagnated tears providing a favorable environment for infectious organisms. The lacrimal sac will then become inflamed, leading to the characteristic erythema and edema at the inferomedial portion of the orbit.

Symptoms and Signs

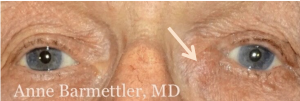

Presentation differs for acute and chronic dacryocystitis. In acute dacryocystitis, the symptoms may occur over several hours to several days and include pain, erythema, and edema over the medial canthus and the area overlying the lacrimal sac at the inferomedial portion of the orbit. The redness can extend to involve the bridge of the nose. Purulent material can sometimes be expressed from the puncta and tearing may be present. In cases of chronic dacryocystitis, excessive tearing and mucus reflux (mucocele) are the most common symptoms. Changes in visual acuity may be present due to altered tear film dynamics.[7]

Erythema involving the entire orbit and pain with extraocular movement are not typically associated with dacryocystitis and should prompt the health care provider to search for alternative diagnoses. Extension of the mass superior to the medial canthus should also prompt imaging and further workup.

Diagnosis

Diagnostic Procedures

The diagnosis of dacryocystitis is generally made based on the patient’s history and physical exam, as described above. In acute cases, the Crigler maneuver, or tear duct massage, can be performed to express material for culture and gram stain. In patients who appear to be acutely toxic or those who present with visual changes, imaging and bloodwork should be considered. In chronic cases, serologic testing can be performed if systemic conditions are suspected. For example, antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody testing may be useful to test for GPA, while antinuclear antibody testing and double-stranded DNA tests can be performed if SLE is suspected.[8] Imaging is not typically needed to make a diagnosis unless suspicion arises based on the history and physical exam (e.g., the patient complains of hemolacria). Computed tomography scans may be performed in cases of trauma. Dacryocystography, or plain film dacrosystogram (DCG), can be performed when anatomic abnormalities are suspected. A subtraction DCG technique can improve the quality of radioimages. Nasal endoscopy is useful to rule out hypertrophy of the inferior turbinate, septal deviation, and inferior meatal narrowing.

The fluorescein dye disappearance test (DDT) is another option available for evaluating adequate lacrimal outflow, especially in patients unable to undergo lacrimal irrigation. In a DDT assay, sterile fluorescein dye is instilled into the conjunctival fornices of each eye, and the tear firms are then examined under a slit lamp. The persistence of dye, coupled with asymmetric clearance of the dye from the tear meniscus after 5 minutes, indicates an underlying lacrimal outflow obstruction.[9] However, this does not distinguish between upper (punctal, canalicular, or sac) and lower (nasolacrimal duct) obstruction.

Differential Diagnosis

- Canaliculitis (syringing patent)

- Acute ethmoid sinusitis

- Infected sebaceous cysts

- Cellulitis

- Eyelid ectropion

- Punctal ectropion

- Allergic rhinitis

- Lacrimal sac or sinonasal tumor

Management

Definitive treatment requires addressing the underlying cause of the dacryocystitis. In most adults, this is a dacryocystorhinostomy (DCR) for the underlying involutional acquired NLDO. In children, a more conservative route is typically followed, as congenital NLDO has up to a 90% chance of resolution by 1 year of age.

First, acute dacryocystitis should be treated with oral empirical antibiotics with gram-positive coverage. Warm compresses and Crigler massages can also be employed in children. In both adults and children, lacrimal probing is discouraged in acute cases to prevent creation of false passages in the friable tissue. If the dacryocystitis is progressing despite oral antibiotic therapy, the patient shows evidence of orbital cellulitis, or the case is otherwise complicated, this may require culture-directed use of intravenous antibiotics.

Once the acute inflammation/infection is controlled, the underlying cause can then be addressed. In children, this is often a blockage at the valve of Hasner, so treatment begins conservatively with Crigler massages (parents are taught how to perform the massage at home), and antibiotics are prescribed for the treatment of acute flares. Patients who fail conservative treatment often undergo lacrimal probing, which is successful in 70% of cases. If the dacryocystitis still persists, additional surgical interventions may be needed, such as stenting, balloon dacryoplasty, and DCR.[10] [11] DCR can be done percutaneously as an external DCR or endoscopically as an endonasal DCR.[7] [12]

Prognosis and Complications

Fortunately, the prognosis of dacryocystitis is generally positive, but devastating complications are possible, so prompt referral to an ophthalmologist is encouraged. Possible complications include the formation of lacrimal fistulas, lacrimal sac abscesses, meningitis, cavernous sinus thrombosis, vision loss, and even death.

References

- ↑ The lacrimal apparatus. In: Newell FW, ed. Ophthalmology: Principles and Concepts. 6th ed. CV Mosby;1986:254-262.

- ↑ Mills DM, Bodman MG, Meyer DR, et al. The microbiologic spectrum of dacryocystitis: a national study of acute versus chronic infection. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;23(4):302-306.

- ↑ Sáenz González AF, Busquet I, Duran N, et al. Chronic dacryocystitis caused by sarcoidosis. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol (Engl Ed). 2019;94(4):188-191.

- ↑ Taylor RS, Ashurst JV. Dacryocystitis. StatPearls Publishing. Published September 11, 2023. Accessed March 25, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470565/

- ↑ Chen L, Fu T, Gu H, et al. Trends in dacryocystitis in China: a STROBE-compliant article. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(26):e11318.

- ↑ Bartley GB. Acquired lacrimal drainage obstruction: an etiologic classification system, case reports, and a review of the literature. Part 1. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;8:237-242.

- ↑ Jump up to: 7.0 7.1 Pinar-Sueiro S, Sota M, Lerchundi T-X, et al. Dacryocystitis: systematic approach to diagnosis and therapy. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2012;14:137-146.

- ↑ Heichel J, Struck HG, Glien A. Diagnostik und Therapie von Tränenwegserkrankungen: Ein strukturiertes patientenzentriertes Versorgungskonzeptconcept. HNO. 2018;66(10):751-759.

- ↑ Guzek JP, Ching AS, Hoang TA, et al. Clinical and radiologic lacrimal testing in patients with epiphora. Ophthalmology.1997;104(11):1875-1881.

- ↑ Cassady JV. Dacryocystitis of infancy: a review of one hundred cases. Arch Ophthalmol.1948;39(4):491-507.

- ↑ Congenital anomalies of the lacrimal system. In:Jones LT, Wobig JL, eds. Surgery of the Eyelids and the Lacrimal System. Aesculapius Publishing Company;1976:157-173.

- ↑ Kumar S, Mishra AK, Sethi A, et al. Comparing outcomes of the standard technique of endoscopic DCR with its modifications: a retrospective analysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;160(2):347-354.