Pseudostrabismus

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Pseudostrabismus refers to the appearance of eye misalignment in the absence of true misalignment of the visual axes. The appearance of eye misalignment may be created by certain morphological features of the face (including the eyelids, interpupillary distance, and nose) or an abnormal angle kappa. Pseudoestropia (the appearance of esotropia) is the most common form of pseudostrabismus, followed by pseudoexotropia and pseudohypotropia/pseudohypertropia.

Prevalence

One retrospective population-based cohort study reported a birth prevalence of pseudostrabismus in 1% of infants during a 10-year study period.[1] Of note, some patients with a diagnosis of pseudostrabismus were later found to have true eye misalignment. The incidence of manifest strabismus following pseudostrabismus diagnosis has been reported to be between 4.9% to 9.6% among infants with pseudostrabismus with and without ophthalmology follow-up. [1][2][3] The pathophysiology behind how children with pseudostrabismus develop strabismus remains unclear, as there is no direct causal association between pseudoestrabismus and true strabismus. One explanation for this association is that selection bias leads parents with persistent concerns for ocular deviation pursue follow-up care leading to higher rates of detecting children who with strabismus in this gropu compared to the general population.[1] Furthermore, it is possible that patients who actually had strabismus were initially misdiagnosed with pseudostrabismus due to these children having intermittent deviation and poor cooperation. [3]

Etiology

Pseudoesotropia

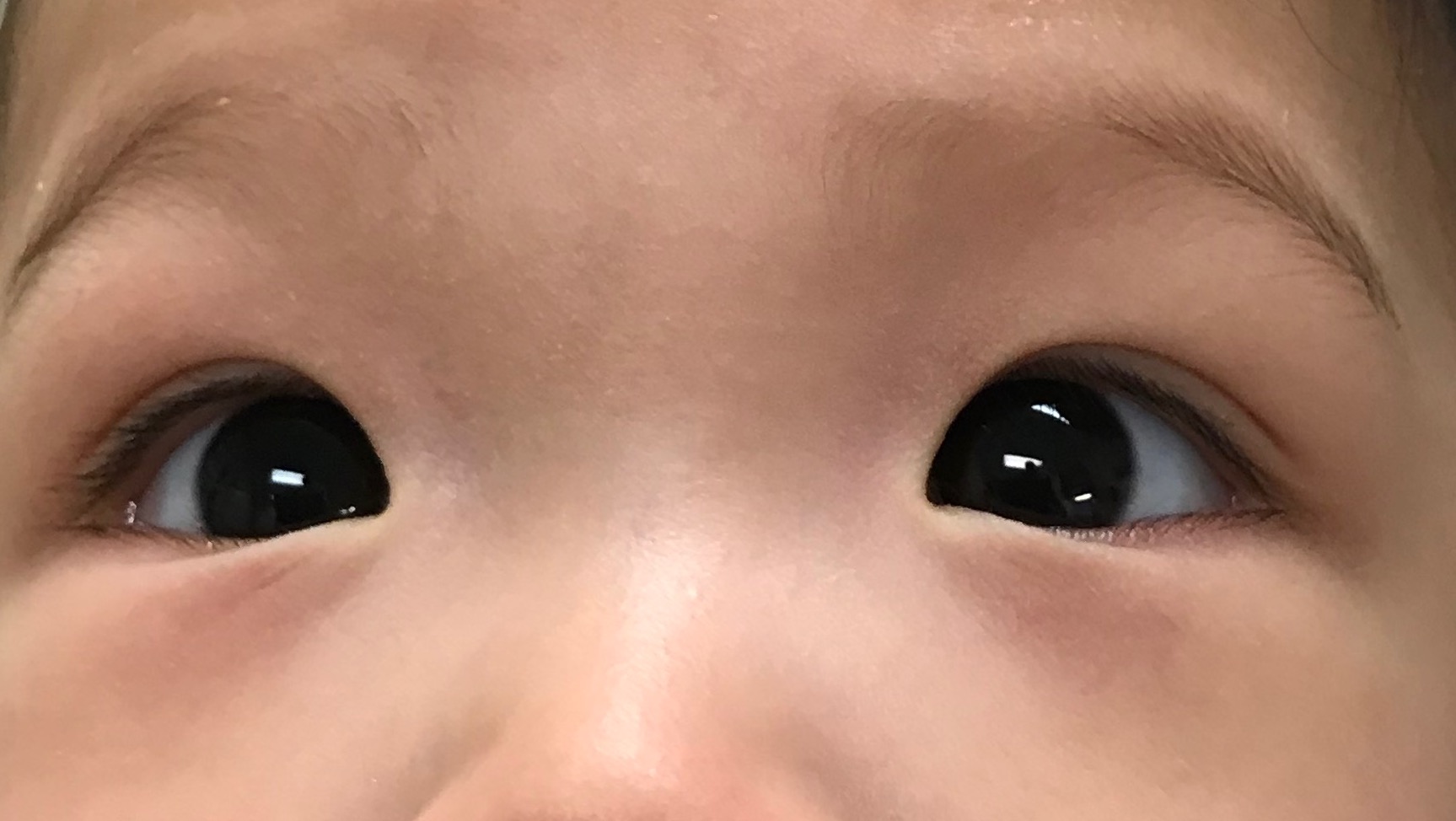

Pseudoesotropia is the most common type of pseudostrabismus. This appearance occurs most commonly in infants who have a wide nasal bridge or prominent epicanthal folds (prominent semilunar folds of skin of the medial upper eyelid). The prominence of the epicanthal folds may decrease as a child’s face grows, thus reducing the appearance pseudoesotropia in some individuals. Patients with a small interpupillary distance may also appear to pseudoesotropic. Finally, a negative angle kappa (wherein the corneal light reflex appears to be on the temporal side of the pupillary center) can also simulate an esodeviation. A negative angle kappa can occur if the fovea has been dragged medially due to a retinal condition.

Pseudoexotropia

Pseudoexotropia occurs most commonly in children with hypertelorism. A positive angle kappa (wherein the corneal light reflex appears to be on the nasal side of the pupillary center) can also simulate an exodeviation. Positive angle kappa can occur in conditions wherein the macula is dragged temporally, such as in advanced cases of retinopathy of prematurity, toxocara, high myopia, or congenital retinal folds.

Pseudohypotropia/Pseudohypertropia

Facial asymmetry may create an appearance of vertically misaligned eyes wherein one eye appears to be higher than the other. Certain orbital tumors or trauma to the orbital floor can also occasions create hypoglobus wherein the entire globe is lower than the other side simulating a vertical misalignment. Additionally eyelid asymmetry, like lid retraction or ptosis, may create the illusion of vertical misalignment of the eyes.

Risk Factors

- Prematurity: Retinopathy of prematurity with temporal dragging of macula can result in positive angle kappa and pseudoexotropia

- Facial Morphology: Asian children have prominent epicanthal folds resulting in pseudoesotropia

- Orbital tumors: can result in pseduohypotropia/pseudohypertropia

- Orbital trauma: can cause hypoglobus resulting in pseudohypotropia in some cases

- Chorioretinal Infections: can cause chorioretinal scarring with temporal dragging of the macula resulting in pseudoexotropia

- Vertical eyelid asymmetry due to various conditions- like Horner's syndrome, thyroid eye disease, trauma may cause pseudohypotropia/pseudohypertropia

Diagnosis

Clinical diagnosis

The diagnosis of pseudostrabismus should only be reached after ruling out the presence of true manifest or intermittent strabismus.

History

Detailed history regarding birth weight, gestational age, the health of the child, history of prior procedures to treat retinopathy of prematurity may give diagnostic clues. History of first presentation aided by photographs of the child in the first few months of life can assist in documenting the onset, detecting the stability of the appearance and confirming the diagnosis.

Physical examination

Physical examination should include visual evaluation, motor evaluation, and inspection of facial morphology (nasal bridge, orbital, and eyelid morphology), cycloplegic refraction, and dilated eye exam.

A detailed ocular motility exam comprising of cover-uncover and alternate cover test should be performed as the gold standard test for true strabismus, but in a uncooperative infant, the Hirschberg's light reflex test may be the only means possible to estimate the relative position of the eyes. A cycloplegic refraction should be performed in every case of pseudoestropia to rule out high hyperopia which may be a sign of intermittent esotropia in patients with accommodative esotropia.

Differential diagnosis

True strabismus should always be ruled out with a thorough exam before diagnosing a patient with pseudostrabismus

Management

Once the diagnosis of pseudostrabismus is confirmed it is important to reassure the family and educate them about the signs of true strabismus in any patient with pseudostrabismus. Family should report back if any evidence of true strabismus is noted as it is important to diagnose a new onset manifest strabismus as early as possible in these patients which can be easily missed in view of a prior diagnosis of pseudostrabismus.

Medical follow up

Most pediatric ophthalmologists follow these patients in 6-12 months to rule out any evidence of true strabismus in future, especially if risk factors are identified for accommodative esotropia, such as high hyperopia.[4]

Prognosis

Most cases of pseudoesotropia due to prominent epicanthal folds resolves by 2 or 3 years of age because the prominence of the epicanthal folds diminish as the bridge of the nose enlarges. Pseudostrabismus secondary to positive or negative angle kappa or other static facial features persist.

Additional Resources

- AAPOS Frequently asked questions about Pseudostrabismus

- Scott Larson, MD. Pseudostrabismus. American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology & Strabismus. https://aapos.org/browse/glossary/entry?GlossaryKey=eafce745-dfbf-48e4-aac4-66b9b05868e8 Accessed July 01, 2019.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Xu TT, Bothun CE, Hendricks TM, Mansukhani SA, Bothun ED, Hodge DO, Mohney BG. Pseudostrabismus in the First Year of Life and the Subsequent Diagnosis of Strabismus. Am J Ophthalmol. 2020 Oct;218:242-246. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2020.06.002. Epub 2020 Jun 10. PMID: 32533950; PMCID: PMC8243359.

- ↑ Silbert AL, Matta NS, Silbert DI. Incidence of strabismus and amblyopia in preverbal children previously diagnosed with pseudoesotropia. J AAPOS. 2012 Apr;16(2):118-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2011.12.146. PMID: 22525164.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Ryu WY, Lambert SR. Incidence of Strabismus and Amblyopia Among Children Initially Diagnosed With Pseudostrabismus Using the Optum Data Set. Am J Ophthalmol. 2020 Mar;211:98-104. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2019.10.036. Epub 2019 Nov 13. PMID: 31730842; PMCID: PMC7073278.

- ↑ Pritchard C, Ellis GS Jr. Manifest strabismus following pseudostrabismus diagnosis. Am Orthopt J. 2007;57:111-7. doi: 10.3368/aoj.57.1.111. PMID: 21149165.