Hypertelorism

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Orbital hypertelorism is an abnormally increased lateral distance between the orbits, and it can also be associated with dystopia. It may be unilateral or bilateral, symmetric or asymmetric, and associated with conditions including craniofacial dysplasia, encephaloceles, and craniosynostosis. [1] When indicated for functional or aesthetic reasons, treatment involves surgery. Hypertelorism should not be confused with telecanthus, in which the distance between the pupils is normal but the medial canthi are widely spaced.

Disease Entity

- ICD 10: Q75.2 - Hypertelorism

Disease

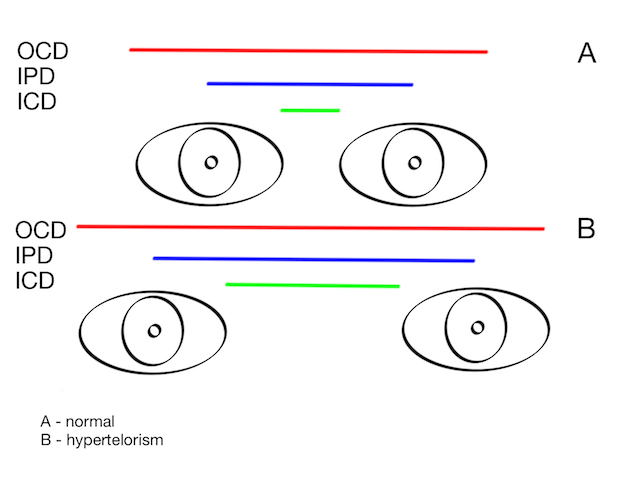

Orbital hypertelorism is a true lateralization of the orbit where the inner canthal distance (ICD), the outer canthal distance (OCD) and interpupillary distance (IPD) are all increased (figure 1). It is typically a manifestation of a craniofacial deformity and not a disease in itself. [1]

Figure 1 – Increased ODC, IPD and ICD in ORH.

Etiology

Orbital hypertelorism can be seen in a variety of conditions such as craniofacial clefts, craniofacial dysplasias and craniosynostosis syndromes,[1] like

- Edwards Syndrome,

- 1q21.1 Duplication Syndrome,

- Basal Cell Nevus Syndrome,

- DiGeorge Syndrome,

- Loeys-Dietz Syndrome

- Hypertelorism is a distinctive craniofacial feature commonly associated with Loeys-Dietz Syndrome (LDS). This condition is one of the hallmark characteristics of LDS, often aiding in the clinical differentiation of LDS from other connective tissue disorders such as Marfan Syndrome and Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome.[2] The presence of hypertelorism in LDS is usually evident from an early age and can be accompanied by other craniofacial abnormalities, including a bifid uvula, cleft palate, and craniosynostosis. [3]The pathogenesis of hypertelorism in LDS is linked to the underlying mutations in genes involved in the transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) signaling pathway. These genetic mutations lead to aberrant craniofacial development during embryogenesis, resulting in the characteristic facial features seen in LDS patients. The craniofacial anomalies, including hypertelorism, are more than just cosmetic concerns; they reflect the widespread impact of the connective tissue disorder and may have implications for surgical management and other interventions.[4]

- In the context of ophthalmology, hypertelorism can influence ocular alignment and the visual axis, potentially contributing to strabismus or other refractive issues. Ophthalmologists, therefore, play a crucial role in the early recognition and management of the ocular and craniofacial manifestations of LDS. Given the association of hypertelorism with LDS, clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for this syndrome when encountering patients with hypertelorism, especially when accompanied by other systemic features suggestive of a connective tissue disorder.

- Crouzon Syndrome,

- Apert Syndrome,

- Noonan syndrome,

- Neurofibromatosis,

- Leopard Syndrome,

- Wolf-Hirschhorn Syndrome,

- Andersen–Tawil Syndrome,

- Waardenburg Syndrome, and

- Cri-du-Chat Syndrome.

Embryology

In orbital hypertelorism, there is a defect in movement of the orbits towards midline, causing the orbits to remain abnormally spaced. Purposed mechanisms include a defective development of the nasal capsule, deficient latero-medial movement of the orbit, early ossification of the lesser wings of sphenoids and a frontonasal prominence that remains in its embryonic position.[1]

Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis

Telecanthus, also known as Pseudo-hypertelorism, is an entity in which the inner canthal distance is increased but the outer canthal distance and interpupillary distance are unchanged. Some Congenital disorders such as Down Syndrome, Fetal Alcohol Syndrome, Cri-du-Chat Syndrome, Klinefelter Syndrome, Turner Syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome and Waardenburg Syndrome can be associated with Telecanthus.

Management

General treatment

Treatment involves corrective surgery and is indicated primarily for aesthetic reasons. The aim is to bring the orbits medially and correct any orbital dystopia or any soft tissue abnormalities.[1]

Surgery

When indicated, surgery is performed between 5 - 7 years old to avoid any injury in the un-erupted tooth roots and maxillary growth disturbances. There are two operative techniques:

- box osteotomy and

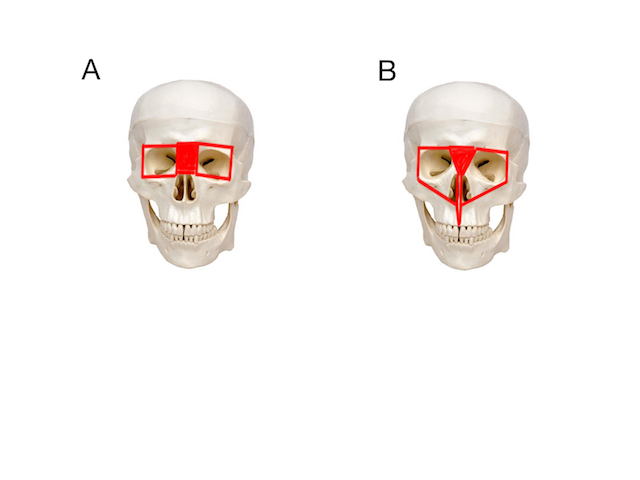

- facial bipartition (figure 2).

Box osteotomy involves an en-bloc movement of the orbits medially into the space created by resection of abnormally wide nasal and ethmoidal bones. A midline excision of skin is frequently necessary due to the excessive skin created. This technique is performed when dental occlusion is normal.

Facial bipartition involves a medial resection of the nasal dorsum in a “V” shaped form, a split in the midline of the palatal bone and a medialization of the two hemifaces. This technique is performed when there are associate dental arch deformities. For a better a result, it is also important to take soft-tissue reconstruction in consideration. It is also important to consider a medial canthopexy for better results.

Figure 2 – A: Box osteotomy; B: Facial bipartition.

Complications

The main complications of both surgeries for orbital hypertelorism correction include excessive bleeding, risk of infection and cerebrospinal fluid leaks. Rare events also include blindness, visual disturbances, ptosis and diplopia.

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Sharma, R. K.; Hypertelorism; Indian Journal of Plastic Surgery, September-December 2014, Vol 47, Issue 3.

- ↑ Baldo F, Morra L, Feresin A, et al. Neonatal presentation of Loeys-Dietz syndrome: two case reports and review of the literature. Ital J Pediatr. 2022;48(1):85. doi:10.1186/s13052-022-01281-y

- ↑ Loomba K, Lin D, Lin W, Riley B. Ocular Manifestations of Loeys–Dietz Syndrome. Published online March 28, 2022. Accessed August 7, 2024.

- ↑ Velchev JD, Van Laer L, Luyckx I, Dietz H, Loeys B. Loeys-Dietz Syndrome. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2021;1348:251-264. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-80614-9_11

- Jackson, T. L.; Moorfields: Manual of Ophthalmology; London, U.K.; Mosby Elsevier, 2008.