Orbital Xanthomas

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Xanthomas are lipid-laden lesions that can develop in tissues throughout the body. In ophthalmic practice they most commonly present as xanthelasma palpebrarum.[1] Xanthomatous lesions are strongly associated with hyperlipidemia, warranting further metabolic work-up. Rarely, xanthomas may signal an underlying systemic condition such as a xanthogranulomatous disease. Xanthelasma palpebrarum can be diagnosed by clinical examination. Orbital xanthomas require biopsy for definitive histopathological diagnosis given their non-specific appearance on imaging. Xanthomas associated with metabolic disorders including hyperlipidemia may recur following excision.

Disease Entity

Xanthoma is derived from the Greek Xanthos, meaning “yellow.” Xanthomas are lipid-laden tumors characterized by foamy macrophages, also called xanthoma cells or foam cells, which can form in connective tissues throughout the body.[2] Xanthomas may be observed as primary tumors, or in conjunction with systemic conditions ranging from common (hyperlipidemia) to uncommon (cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis). This article will focus on xanthomatous lesions and associated conditions that involve the orbit.

Disease Classification

Primary Xanthomas

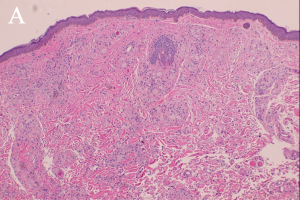

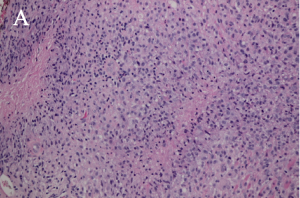

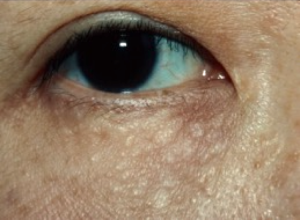

"Xanthoma” is a broad term referring to a tumor that is characterized by the presence of xanthoma cells, also called foam cells (Images 1A, 1B). These lipid-laden macrophages contain elevated levels of carotene, which give the lesions their yellow color. The most common type of xanthoma encountered in ophthalmic practice is xanthelasma palpebrarum,[1] which are superficial xanthomas found on the eyelids (Images 2A, 2B). Xanthomas of bone involving the orbit have been reported[3][4] and xanthomas in orbital soft tissue have been rarely reported (Images 6 and 7).[5] Xanthoma verrucum (oral), xanthoma tuberosum (articular), and xanthoma planum (dermal) are other examples of xanthomas found in specific regions.

Systemic Xanthomatous Disorders

Several uncommon systemic conditions are associated with xanthomas involving the eyes. Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis (CTX) is an autosomal recessive metabolic storage disorder that may present with xanthelasma palpebarum. Other ocular manifestations include bilateral cataracts (due to accumulation of cholestenol), optic nerve atrophy, and proptosis.

Xanthoma disseminatum is a rare, non-familial, non-Langerhans cell, normolipidemic disorder associated with diabetes insipidus that involves mucocutaneous xanthomas and histiocytic deposits. These deposits are most often found on flexural surfaces and intertriginous areas, but they can involve the cornea, the conjunctiva, and mucous membranes.[6] There is one report of a young child with neurologic involvement including optic atrophy. [7]

Alagille syndrome is an autosomal dominant disease characterized by cutaneous xanthomas. The ocular manifestations include iris abnormalities, posterior embryotoxon, optic disc changes (hypoplasia, tilting, or elevation), and hypopigmentation of the choroid and retina.

Sitosterolemia is an autosomal recessive disorder of lipid metabolism. Most manifestations involve sequelae of severe premature atherosclerosis, and many patients develop superficial xanthomas over tendons and joints. There is one report of a xanthomatous orbital soft tissue mass identified in a patient with sitosterolemia.[8] Interestingly, despite the high serum lipid levels that define this condition, xanthelasma palpebarum are not characteristic of this disease.

Xanthogranulomatous disorders

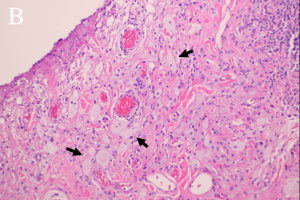

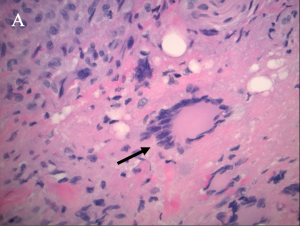

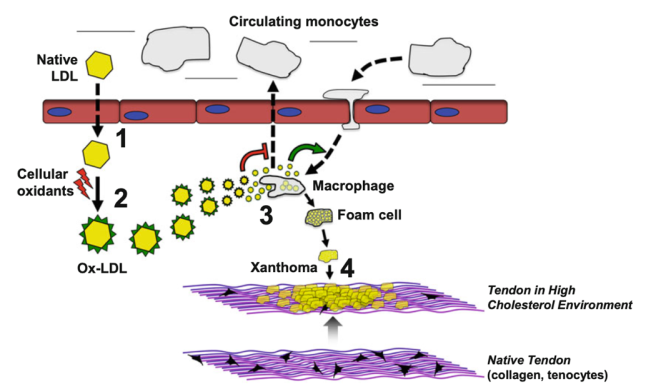

There are four subtypes of adult xanthogranulomatous disorders and one juvenile xanthogranuloma. Xanthogranulomatous disorders are non-Langerhans histiocytoses. Like xanthomas, the lesions in these disorders contain foam cells; they differ from xanthomas in the presence of Touton giant cells, a type of multinucleated giant cell with a high lipid content, and varying degrees of fibrosis and necrosis (Images 3A, 3B).

Juvenile xanthogranuloma (JXG) is the most common form of non-Langerhans histiocytosis and affects children. The eye is the most frequent extracutaneous site of involvement, and xanthomatous lesions are most often found on the iris. This condition tends to be self-limited and response to steroid treatment.[9]

Adult onset xanthogranuloma (AOX) is the presence of a xanthogranulomatous lesion – which may involve the orbit – without systemic involvement.[9]

Adult onset asthma and periocular xanthogranuloma (AAPOX) is a syndrome that involves asthma, xanthogranulomatous lesions, and often lymphadenopathy and elevated IgG levels.[9] AAPOX was first described in 1993 by Jakobiec et al as a periocular xanthogranulomatous syndrome in patients with severe adult-onset asthma.[10] These lesions tend to appear as orbital masses or fullness, though patients can also have xanthelasma-like eyelid lesions.[10] More recently it has been shown to share many clinical, histopathological and immunohistochemical features with IgG4-related disease.[11]

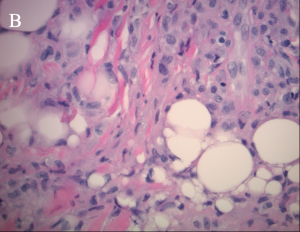

Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma (NXG) is a rare autosomal recessive metabolic storage disorder affecting bile acid synthesis. Ocular manifestations include xanthelasma palpebarum, which may have a necrotic aspect, as well as orbital masses and ocular inflammatory conditions (Images 4A, 4B, and 5).

Erdheim-Chester disease (ECD) is the most life-threatening of the xanthogranulomatous conditions and is characterized by fibrosclerosis of internal organs (including the pericardium, mediastinum, and pleural spaces) and the orbit. Unlike in AOX, AAPOX and NXG, where orbital involvement tends to be more anterior, patients with ECD have diffuse orbital involvement with vision loss.[9]

Risk Factors

The presence of xanthomas can point to serious underlying metabolic, cardiovascular and lymphoproliferative disorders. Xanthomas are associated with hyperlipidemia, specifically elevated LDL, triglycerides and/or cholesterol.[12][13][14] Traditionally, xanthelasma in particular may be associated with smoking, central obesity, hypertension and diabetes in addition to hyperlipidemia.[13]However, a recent study demonstrated that there is no increased cardiovascular or metabolic risk in patients that present with xanthelasma alone. [15]

Familial conditions confer an increased risk of xanthomas. Autosomal dominant hypercholesterolemia including familial hypercholesterolemia, is secondary to mutations in the genes encoding the LDL receptor (LDL-R); familial defective apolipoprotein B-100, due to mutations in the gene APOB; and hypercholesterolemia associated with mutations in the gene PCSK9.[2]

Monoclonal gammopathies can be associated with specific xanthomas or xanthogranulomatous conditions. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma and diffuse plane (cutaneous) xanthomas have been reported in normolipidemic patients with multiple myeloma or other monoclonal gammopathies.[16][17][18]

General Pathology

Xanthomatous lesions consist of mononuclear macrophage-like cells, foam cells, and multinucleated giant cells within layers of histiocytes (Images 1A, 1B). The xanthoma cells are positive for CD68 and vimentin.[19] There is often a surrounding lymphocytic infiltrate.

Xanthogranulomas differ from xanthomas by the presence of Touton giant cells, a type of multinucleated giant cells with high lipid content, and areas of necrosis (Images 3A, 3B, 4A, 4B).

Pathophysiology

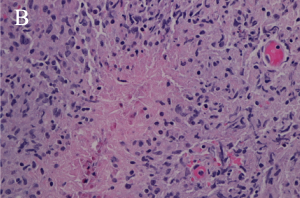

The development of xanthomas begins with the movement of lipoproteins out of the vascular system and into the interstitium, with subsequent metabolism by macrophages and ultimately the development of foam cells (Figure 1).[20] This mechanism is true in both hyperlipidemic and normolipidemic states; in hyperlipidemia, elevated levels of circulating lipoproteins in the blood cause some of the excess lipids to permeate into surrounding tissues, while in normolipidemia it is postulated that inflammation with increased vascular permeability plays a more primary role.[21] Chronic inflammation in hyperlipidemia likely contributes to vascular permeability as well.[2]

Macrophages and monocytes in the interstitial space intake lipids via phagocytosis of LDL and lipid complexes. The movement of these white blood cells into the interstitial space containing extruded lipoproteins supports the theory that inflammation is an important underlying mechanism in xanthoma formation.[2] LDL undergoes oxidative modification, and macrophages take up oxidized LDL with greater affinity than other cells via their expression of scavenger receptors (which preferentially bind oxidized LDL). Oxidative modification is accelerated by ferritin and inhibited by some antioxidants,[22] further supporting the role of inflammation. This has been demonstrated in a group of patients with familial hypercholesterolemia, in whom those with xanthomas had higher plasma levels of TNF, IL-6, and IL-8 inflammatory markers.[23]

Reverse cholesterol transport, a process with allows excess cholesterol to leave tissue, is also a component of xanthoma formation. Normally, elevated cholesterol in interstitium/tissues stimulates a feedback mechanism that inhibits de novo lipid synthesis in that tissue; when macrophage scavenger receptors bind cholesterol, that cholesterol cannot trigger the feedback loop and the regulatory feedback mechanism of de novo lipid synthesis is impaired .[2] Additionally, HDL normally serves as a cholesterol acceptor, aiding in the movement of cholesterol out of tissues; low levels of HDL have been reported in “normolipidemic” patients with xanthomas[24] (Figure 1).

The lipids found within xanthomas are a combination of unesterified cholesterol, cholesteryl esters, and phospholipids.[2]

Diagnosis

Physical examination

Xanthelasma is a clinical diagnosis that only requires biopsy if the appearance is atypical. Xanthomas of the orbit will present as an orbital mass that may be palpable and may cause globe displacement if large (Image 6).

Diagnostic procedures

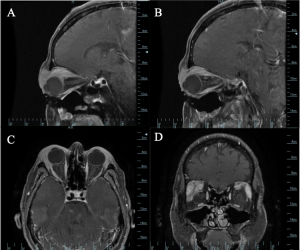

Imaging may be warranted for deeper xanthomas that present as an orbital mass, especially because the findings on CT and MRI are non-specific. Xanthomas may appear as well-circumscribed masses or as diffuse heterogenous enhancement surrounding orbital structures (Image 7).[4]

Bone xanthomas can have a varied appearance on imaging. On CT, the lesions may be well-defined, or they may have poorly defined borders. They often appear radiolucent with sclerotic margins and those in the craniofacial area tend to appear lytic.[3]

Histopathological analysis is essential for diagnosis of deep xanthomas as the imaging findings are non-specific.

Laboratory testing

Work up for dyslipidemia and other metabolic disorders is warranted in any patient with a xanthomatous lesion, including a comprehensive metabolic panel and lipid levels.

Although traditionally, patients presenting with xanthelasma have been advised that 90% of patients may have a lipid abnormality, a recent study demonstrated that there is no increased cardiovascular or metabolic risk in patients that present with xanthelasma alone.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of patients presenting with xanthelasma or xanthomas, include the xanthogranulomatous disorders (necrobiotic xanthogranuloma, juvenile xanthogranuloma, adult-onset asthma with periocular xanthogranuloma). Erdheim-Chester disease is a life-threatening non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis that can include xanthelasma and is characterized by internal organ fibrosis. Syringomas (Image 9) are benign eccrine tumors that can resemble xanthelasma (Images 2A, 2B).

Xanthomas may present as orbital masses (Images 6 and 7) and the differential diagnosis can be extensive even after imaging, including inflammatory lesions, benign tumors and histiocytic disorders.

Bone xanthoma is rare and can appear similar to more common bone lesions on imaging, including benign fibrous histiocytoma, non-ossifying fibroma, simple bone cyst, fibrous dysplasia, giant cell tumor, or brown tumor of hyperparathyroidism.

Management

Surgical excision may be definitive, if the lesion is well defined. Surgical biopsy confirms the diagnosis. However, xanthomas associated with hyperlipidemia or other metabolic disorders may not be well defined anatomically and may not be amenable to complete excision. They also do tend to recur.[21] Work-up should include a comprehensive metabolic panel and lipid levels, and if abnormal, should be managed through diet, lifestyle modification and lipid-lowering medications. Any other metabolic or systemic disease should be identified and addressed.

For management of xanthelasma and xanthogranulomatous conditions, see the corresponding EyeWiki pages.

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 Govorkova MS, Milman T, Ying GS, Pan W, Silkiss RZ. Inflammatory Mediators in Xanthelasma Palpebrarum: Histopathologic and Immunohistochemical Study. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2018;34(3):225-230

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Zak A, Zeman M, Slaby A, Vecka M. Xanthomas: clinical and pathophysiological relations. Biomedical papers of the Medical Faculty of the University Palacky, Olomouc, Czechoslovakia. 2014;158(2):181-188. doi:10.5507/bp.2014.016

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.0 3.1 Matoba M, Tonami H, Kuginuki M, Yamamoto I, Akai T, Iizuka H. CT and MRI findings of xanthoma in the orbitofrontal region. Radiation medicine. 2004;22(2):116-119.

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 Matoba M, Tonami H, Kuginuki M, Yamamoto I, Akai T, Iizuka H. CT and MRI findings of xanthoma in the orbitofrontal region. Radiation medicine. 2004;22(2):116-119.

- ↑ Kodsi S, Valderrama E. Orbital xanthoma in a 9-month-old infant. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 2001;131(1):150-151. doi:10.1016/S0002-9394(00)00725-X

- ↑ Altman J, Winkelmann R. Xanthoma Disseminatum. Archives of Dermatology. 1962;86(5):582. doi:10.1001/archderm.1962.01590110018003

- ↑ Patra S, Bhatia S, Khaitan BK, Bhari N. Xanthoma disseminatum with neurological involvement and optic atrophy: improvement with cladribine. BMJ Case Reports. 2019;12(5): e228464. doi:10.1136/bcr-2018-228464

- ↑ Okafor LO, Bowyer J, Thaung C, Murphy E, Verity DH. Orbital involvement of Sitosterolemia. Orbit (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2020;9(17):1-5. doi:10.1080/01676830.2020.1820534

- ↑ Jump up to: 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Sivak-Callcott JA, Rootman J, Rasmussen SL, et al. Adult xanthogranulomatous disease of the orbit and ocular adnexa: new immunohistochemical findings and clinical review. The British Journal of Ophthalmology. 2006;90(5):602-608. doi:10.1136/bjo.2005.085894

- ↑ Jump up to: 10.0 10.1 Jakobiec FA, Mills MD, Hidayat AA, et al. Periocular xanthogranulomas associated with severe adult-onset asthma. Transactions of the American Ophthalmological Society. 1993; 91:99-129.

- ↑ London J, Martin A, Soussan M, et al. Adult-Onset Asthma and Periocular Xanthogranuloma (AAPOX), a Rare Entity with a Strong Link to IgG4-Related Disease: An Observational Case Report Study. Medicine. 2015;94(43): e1916. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000001916

- ↑ Zhimin W, Hui W, Fengtao J, Wenjuan S, Yongrong L. Clinical and serum lipid profiles and LDLR genetic analysis of xanthelasma palpebrarum with nonfamilial hypercholesterolemia. Journal of cosmetic dermatology. 2020;19(11):3096-3099. doi:10.1111/jocd.13366.

- ↑ Jump up to: 13.0 13.1 Dey A, Aggarwal R, Dwivedi S. Cardiovascular profile of xanthelasma palpebrarum. BioMed research international. 2013; 2013:932863. doi:10.1155/2013/932863.

- ↑ Kavoussi H, Ebrahimi A, Rezaei M, Ramezani M, Najafi B, Kavoussi R. Serum lipid profile and clinical characteristics of patients with xanthelasma palpebrarum. Anais Brasileiros de Dermatologia. 2016;91(4):468-471. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20164607.

- ↑ Lustig-Barzelay Y, Kapelushnik N, Goldshtein I, Leshno A, Segev S, Ben-Simon GJ, Landau-Prat D. Association Between Xanthelasma Palpebrarum with Cardiovascular Risk and Dyslipidemia: A Case Control Study. Ophthalmology. 2024 Aug 5:S0161-6420(24)00458-5. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2024.07.033. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 39111668.

- ↑ Cohen YK, Elpern DJ. Diffuse normolipemic plane xanthoma associated with monoclonal gammopathy. Dermatology practical & conceptual. 2015;5(4):65-67. doi:10.5826/dpc.0504a16

- ↑ Adam Z, Zahradová L, Krejcí M, et al. Diffuse plane normolipemic xanthomatosis and necrobiotic xanthogranuloma associated with monoclonal gammopathy--determining the disease stage with PET-CT and treatment experience. Two case studies and literature review. Vnitrni lekarstvi. 2010;56(11):1158-1168.

- ↑ Kim JG, Kim HR, You MH, Shin DH, Choi JS, Bae YK. Necrobiotic Xanthogranuloma Coexists with Diffuse Normolipidemic Plane Xanthoma and Multiple Myeloma. Annals of dermatology. 2020;32(1):53-56. doi:10.5021/ad.2020.32.1.53.

- ↑ Alden KJ, McCarthy EF, Weber KL. Xanthoma of bone: a report of three cases and review of the literature. The Iowa orthopaedic journal. 2008; 28:58-64.

- ↑ Soslowsky LJ, Fryhofer GW. Tendon Homeostasis in Hypercholesterolemia. In: Metabolic Influences on Risk for Tendon Disorders.; 2016:151-165. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-33943-6_14

- ↑ Jump up to: 21.0 21.1 Bell A, Shreenath AP. Xanthoma. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing LLC; 2021:1-12.

- ↑ Wen Y, Leake DS. Low density lipoprotein undergoes oxidation within lysosomes in cells. Circulation research. 2007;100(9):1337-1343. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.151704

- ↑ Artieda M, Cenarro A, Junquera C, et al. Tendon xanthomas in familial hypercholesterolemia are associated with a differential inflammatory response of macrophages to oxidized LDL. FEBS letters. 2005;579(20):4503-4512. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.06.087

- ↑ Matsuura F, Hirano K ichi, Koseki M, et al. Familial massive tendon xanthomatosis with decreased high-density lipoprotein-mediated cholesterol efflux. Metabolism: clinical and experimental. 2005;54(8):1095-1101. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2005.03.014.