Necrobiotic Xanthogranuloma

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Necrobiotic Xanthogranuloma (NXG) is a non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis with multisystem involvement that commonly affects the skin and periorbital structures. There has recently been development of diagnostic criteria for this disease which include physical exam findings, pathologic analysis, and laboratory test abnormalities. There is a strong association with plasma cell dyscrasias and lymphoproliferative disorders. There are no consensus guidelines on specific treatment for NXG which can include topical as well as systemic therapies often in parallel with management of the hematologic disorders.

Disease Entity

Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma (NXG) is classified as a type of non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis. It is a chronic, granulomatous, multisystem disorder that was first described in 1980 by Kossard and Winkelmann.[1] The condition typically presents with firm, yellow-to-orange, xanthomatous plaques and nodules that have a propensity for ulceration and scarring and a predilection for the periorbital region.[2] The disease may involve other sites including the heart, lung, gastrointestinal tract, and liver, and is strongly linked with plasma cell dyscrasias and lymphoproliferative disorders.[1][2] [3][4][5][6]

Etiology

There are no known causes but there is a strong association with paraproteinemias. The link between these conditions is unknown.

Risk Factors

The average age of onset is the sixth decade of life and the disease generally affects men and women equally.[2][3][4][7][8][9][10] Many patients with NXG have previously been diagnosed with or ultimately will be diagnosed with a paraproteinemia such as monoclonal gammopathy of unknown significance (MGUS) or multiple myeloma.

General Pathology

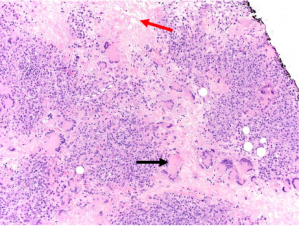

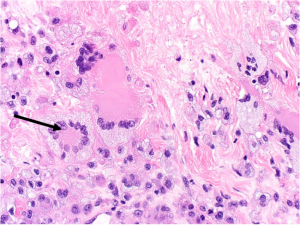

Histopathologically, non-ulcerated NXG lesions are characterized by normal epidermis and superficial dermis. Palisading xanthogranulomas with lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate and zones of necrobiotic collagen are seen in the mid-dermis and subcutaneous tissue (Figure 1A). Cholesterol clefts and both Touton giant cells and large, bizarre foreign body giant cells are other classic features (Figure 1B).[3]

Pathophysiology

While the pathogenesis of NXG has not been elucidated, its association with monoclonal gammopathies highlights paraproteins as a possible inciting or contributory stimulus in generating a giant cell granulomatous reaction.[10] One hypothesis is that monoclonal immunoglobulins bind to lipoproteins and lead to increased uptake by macrophages. This hypothesis also takes into account that NXG patients tend to have lower HDL levels which theoretically leads to decreased reverse transport of cholesterol from target organs, such as the skin.[7][11]

Primary Prevention

None.

Diagnosis

In 2020, Nelson et al.[3] proposed the following diagnostic schematic for NXG, whereby both major criteria and at least one minor criterion are required for diagnosis. This schema is only applicable in the absence of foreign body, infection, or other identifiable causes.

Major Criteria

- Cutaneous papules, plaques, and/or nodules, most often yellow or orange in color.

- Histopathological features demonstrating palisading granulomas with lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate and zones of necrobiosis. Characteristic features that are variably present include cholesterol clefts and/or giant cells (Touton or foreign body).

Minor Criteria

- Paraproteinemia, most often IgG-κ, plasma-cell dyscrasia, and/or other associated lymphoproliferative disorder.

- Periorbital distribution of cutaneous lesions.

History

Patients may describe changes in periorbital skin with or without pruritus or pain. Roughly half of patients (54%) develop a hematologic disorder prior to onset of NXG and 77-84% of patients with NXG will ultimately develop a hematologic disorder, most commonly a paraproteinemia, at some point during their lifetimes. Roughly 50-60% of individuals with NXG and associated paraproteinemia have elevated levels of IgG-Kappa. Progression to multiple myeloma has been seen up to six years after onset of NXG.[3]

Physical Examination

The characteristic skin lesion is an asymptomatic, indurated, papule, nodule, or plaque with a yellow-to-orange hue; these lesions are typically numerous and most often involve the periorbital region (Figure 2A&B). Associated features may include telangiectasias, ulceration, and scarring and new lesions frequently develop at sites of prior scarring.[1][3][4][7][8][9][10]

Cutaneous lesions may also be found on the remainder of the face, the trunk, and the proximal extremities.[3] Approximately 50% of NXG patients have ophthalmic manifestations which may include orbital masses, conjunctival lesions, and inflammatory conditions including episcleritis, scleritis, and keratitis. Mass effect and/or inflammation may result in proptosis and restrictive strabismus in the orbit and ptosis, ectropion and lagophthalmos of the periorbita.[1][10][12][13]

Laboratory test

Serum protein electrophoresis is strongly recommended if the patient has no previous confirmed diagnosis of monoclonal gammopathy, paraproteinemia, or other lymphoproliferative disorder.[3][7] Other lab tests that may be supportive of a diagnosis, but are not required include:

- Complement levels: Low levels of C4 are present in 64% of patients with NXG.[3]

- Vitamin D panel: NXG patients may have low 25-hydroxyvitamin D with normal or high 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D.[14][15]

- Cryoglobulin level: Cryoglobulinemia may be present in 23% of patients with NXG.[7][11][14][15]

- Lipid panel: NXG has been associated with low high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol levels, especially HDL-3C.[3][11]

Differential diagnosis

Other conditions which may mimic NXG include: necrobiosis lipoidica,[16] normolipemic plane xanthomas, xanthelasma,[17] xanthoma disseminatum, multicentric reticulohistiocytosis, juvenile xanthogranuloma, Erdheim-Chester disease,[13] foreign body granulomas, sarcoidosis, nodules of rheumatoid arthritis, subcutaneous granuloma annulare,[18] and amyloidosis.

Management

Optimal treatment of NXG has yet to be detailed, as there have not yet been any prospective, randomized controlled trials to determine the preferred approach given its rarity. In 2016, Miguel et al.[19] performed a systematic review and developed a treatment algorithm for management of the condition. The crucial factor in determining the appropriate treatment course is presence of an associated malignancy. Therapies that have been reported in the literature include:

Topical Therapies:

- Topical or intralesional corticosteroids[20]

- Sub-tenon’s periocular triamcinolone for NXG-associated scleritis

- Interferon alpha

Systemic Therapies:

- Corticosteroids

- Cyclosporine[21]

- Antimetabolites

- Infliximab

- Intravenous immunoglobulin[22][23]

- Plasmapheresis

- Alkylating agents

- Cladribine

Long-term remission of ocular and systemic symptoms was achieved in one patient with monthly IVIG and daily thalidomide, cyclophosphamide, and low-dose oral prednisone.[24]

PhotoTherapies:

- Laser directed at periorbital lesions.

- Reports have shown success with Q-switched 650 nm wavelength laser and carbon dioxide laser but not Nd-YAG laser.

- Radiotherapy

- Psoralen and ultraviolet A radiation (PUVA) with 8-methoxypsoralen

Surgery

Surgical excision of skin lesions is generally not indicated as there is a high subsequent recurrence rate up to 40% in one series of patients.[3][4][19] Surgery may be recommended in specific circumstances, when lesions are affecting vision or negatively impacting ocular health, such as in cases of severe cicatricial ectropion and lagophthalmos.[19]

Complications

End-stage complications of NXG may include organ dysfunction or death, primarily as a result of the underlying hematologic malignancy rather than the NXG specifically. Blindness, while rare, may also occur secondary to exposure keratopathy[25] or from severe, NXG-associated scleritis.[26][27]

Prognosis

Cutaneous lesions may progress without treatment. Patients may develop comorbid hematologic conditions, such as a plasma cell dyscrasia or lymphoproliferative disorder, over time.

Monitoring

Hematologic surveillance is always recommended, given the significant risk of developing lymphoproliferative disorders such as multiple myeloma, even years after NXG presentation. Regular Ophthalmology examinations are recommended given ocular surface and orbital manifestations noted above.

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Kossard S, Winkelmann RK. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma. Australas J Dermatol. 1980;21(2):85-88.

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 2.2 Alikhan A, Hocker T. General Dermatology. In: Review of Dermatology; 2017:132.

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 Nelson CA, Zhong CS, Hashemi DA, et al. A multicenter cross-sectional study and systematic review of necrobiotic xanthogranuloma with proposed diagnostic criteria. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(3):270-279.

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Ugurlu S, Bartley GB, Gibson LE. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma: Long-term outcome of ocular and systemic involvement. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;129(5):651-657.

- ↑ Hunter L, Burry AF. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma: A systemic disease with paraproteinemia. Pathology. 1985;17(3):533-536.

- ↑ Hilal T, DiCaudo DJ, Connolly SM, Reeder CB. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma: A 30-year single-center experience. Ann Hematol. 2018;97(8):1471-1479.

- ↑ Jump up to: 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Szalat R, Arnulf B, Karlin L, et al. Pathogenesis and treatment of xanthomatosis associated with monoclonal gammopathy. Blood. 2011;118(14):3777-3784.

- ↑ Jump up to: 8.0 8.1 Higgins LS, Go RS, Dingli D, et al. Clinical features and treatment outcomes of patients with necrobiotic xanthogranuloma associated with monoclonal gammopathies. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2016;16(8):447-452.

- ↑ Jump up to: 9.0 9.1 Winkelmann RK, Litzow MR, Umbert IJ, Lie JT. Giant cell granulomatous pulmonary and myocardial lesions in necrobiotic xanthogranuloma with paraproteinemia. Mayo Clin Proc. 1997;72(11):1028-1033.

- ↑ Jump up to: 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Goodman WT, Barrett TL. Histiocytoses. In: Dermatopathology; 2018:1625-1626.

- ↑ Jump up to: 11.0 11.1 11.2 Szalat R, Pirault J, Fermand JP, et al. . Physiopathology of necrobiotic xanthogranuloma with monoclonal gammopathy. J Intern Med. 2014;276(3):269-284.

- ↑ Robertson D, Winkelmann R. Ophthalmic features of necrobiotic xanthogranuloma with paraproteinemia. AJO. 1984;97(2):173-183.

- ↑ Jump up to: 13.0 13.1 Wood AJ, Wagner MVU, Abbott JJ, Gibson LE. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma: A review of 17 cases with emphasis on clinical and pathologic correlation. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145(3):279–284.

- ↑ Jump up to: 14.0 14.1 Sfeir JG, Zogala RJ, Popii VB. Hypercalcemia in necrobiotic xanthogranuloma: First reported case and insight into treatment. J Bone Miner Res. 2017;32(4):784-787.

- ↑ Jump up to: 15.0 15.1 Sodhi A, Aldrich T. Vitamin D supplementation: Not so simple in sarcoidosis. Am J Med Sci. 2016;352(3):252-257.

- ↑ Lavy TE, Fink AM. Periorbital necrobiosis lipoidica. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 1992;76:52-53.

- ↑ Patadia A, Rana H, Yen M, et al. Xanthelasma. AAO EyeWiki. May, 2021. https://eyewiki.aao.org/Xanthelasma. Accessed October 9th, 2021.

- ↑ Sandwich JT, Davis LS. Granuloma annulare of the eyelid: A case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 1999 Sep-Oct;16(5):373-6.

- ↑ Jump up to: 19.0 19.1 19.2 Miguel D, Lukacs J, Illing T, Elsner P. Treatment of necrobiotic xanthogranuloma—A systematic review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(2):221-235.

- ↑ Henning C, Meyers S, Swift R, Eades B, Bussell L, Spektor TM, Berenson JR. Efficacy of topical use crisaborole 2% ointment for treatment of necrobiotic xanthogranuloma associated with multiple myeloma. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020 Aug;20(8):e492-e495.

- ↑ Lee, H.-J., Kim, J.-M., Kim, G.-W., Kim, H.-S., Kim, B.-S., Kim, M.-B. and Ko, H.-C. (2017), Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma treated with a combination of oral methylprednisolone and cyclosporin. J Dermatol, 44: 1190-1191.

- ↑ Goyal A, O'Leary D, Vercellotti G, Miller D, McGlave P. Intravenous immunoglobulin for treatment of necrobiotic xanthogranuloma. Dermatol Ther. 2019 Jan;32(1):e12744.

- ↑ Olson RM, Harrison AR, Maltry A, Mokhtarzadeh A. Periorbital necrobiotic xanthogranuloma successfully treated with intravenous immunoglobulin. Case Rep Ophthalmol. 2018 Jan 17;9(1):70-75.

- ↑ Gonzales JA, Haemel A, Gross AJ, Acharya NR. Management of uveitis and scleritis in necrobiotic xanthogranuloma. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2017 May;33(4):325-333.

- ↑ Reddy VC, Salomão DR, Garrity JA, Baratz KH, Patel SV. Periorbital and ocular necrobiotic xanthogranuloma leading to perforation. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128(11):1493–1494.

- ↑ Alkatan H, Al-Abdullah AEA. Orbital necrobiotic xanthogranuloma: A Case Report. Int J Pathol Clin Res. 2015;1:016

- ↑ Keorochana N, Klanarongran K, Satayasoontorn K, Chaiamnuay S. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma scleritis in a case of granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener's granulomatosis). Int Med Case Rep J. 2017;10:323-328.