Juvenile Xanthogranuloma

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Juvenile xanthogranuloma (JXG) is a rare benign histiocytic proliferation that develops in infants and young children. JXG is the most common form of non-Langerhans’ cell histiocytoses. It is characterized by the presence of Touton giant cells.[1]

Clinical Presentation

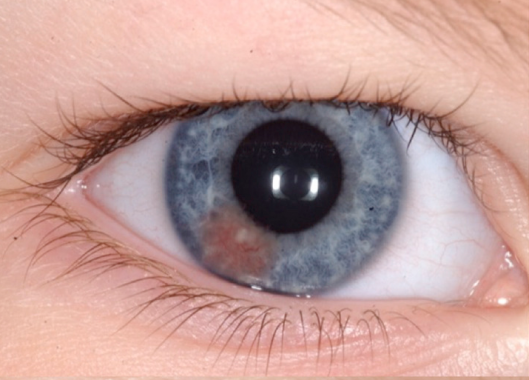

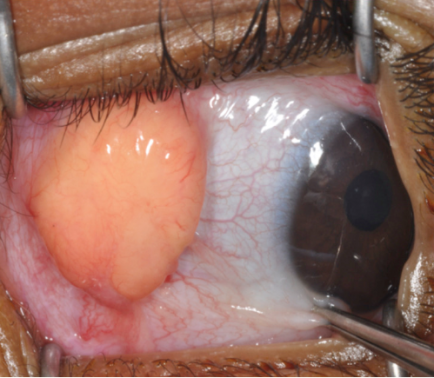

While the majority of cases present as a solitary cutaneous nodular lesion, the eye is the most frequent extracutaneous site of JXG. Among ocular tissues, the iris is most commonly affected, although eyelid, orbital, conjunctival, retinal, choroid and optic disc involvement has been reported.[2][3][4][5][6][7] Skin lesions are present in 75% of patients as the sole manifestation of disease and can be found throughout the body including eyelids, other parts of the head and neck, trunk, and extremities.[8][9][10][11] These lesions usually appear as discrete, round and firm papules that may be brown, red or yellow (see Figure 1). The size of a single papule has been reported to vary from 1 to 20mm, with a wide range in the number of lesions.[10][12][13] They typically stabilize or regress spontaneously in one to five years.[8][9][10] Regressed skin lesions often are flat and wrinkled in appearance and may leave atrophic hypopigmented scars.[11] Iris lesions are the most common intraocular manifestation of the disease (68%)[2] and virtually always unilateral.[1] Iris lesions may be localized, yellowish, vascularized elevated masses or appear as a diffuse thin layer on the iris surface, causing heterochromia (Figure 2).[2] Spontaneous hyphema can occur from these lesions and may lead to secondary glaucoma. 0.3-10% of patients with cutaneous JXG were found to have ocular involvement.[10][13] In patients with ocular JXG, the conjunctiva (19%) was the second most common site.[2] Conjunctival lesions present as a localized yellow nodule on the bulbar conjunctiva (Figure 3).[2]

Other less frequently involved extracutaneous sites include the pericardium, lungs, viscera, bones, kidneys, central nervous system, ovaries, testes and salivary glands.[14][15]

Pathophysiology

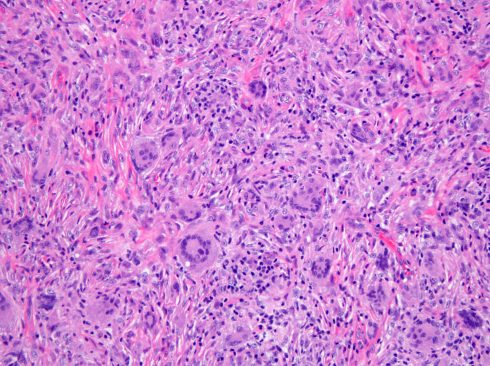

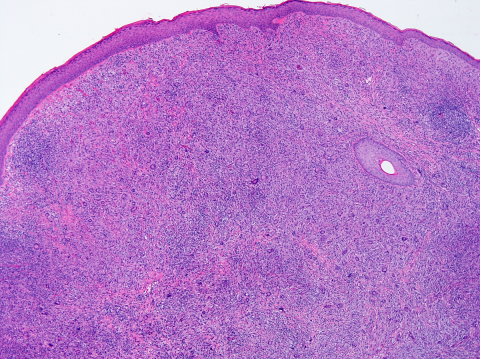

The pathogenesis of JXG is thought to be of reactive origin, namely local tissue injury that evoked a histioxanthomatous reaction.[13] Histologically, the cutaneous infiltrate includes a mixture of foamy histiocytes, lymphocytes, fibroblasts and multinucleated giant cells, including Touton-type giant cells, with a moderate amount of collagen deposition (Figures 4-5). A Touton giant cell is a multinucleated cell that contains a wreath of nuclei surrounding homogeneous cytoplasm, with a rim of foamy cytoplasm peripheral to the nuclei. Other inflammatory cells may be present to varying degrees.[16] JXG cells stain positive for CD68, have variable reactivity for factor XIIIa and stain negative for CD1a, S100, CD20716. JXG does not carry BRAF V600E mutation, except in patients with both Langerhans’ cells histiocytosis (LCH) and JXG (non-Langerhans' cells histiocytosis) diseases and in the aggressive forms of JXG.[8] Development of JXG after chemotherapy for LCH has been reported in 11 patients.[16] One theory proposed the coexistence of LCH and JXG could be the result of chemotherapy-induced maturation of Langerhans’ cells into macrophages, in particular foamy cells.[17] Another theory hypothesized that JXG may be triggered by LCH lesions through the production of a cytokine storm.[9][16]

Disease Association

JXG has been associated with neurofibromatosis 1, Niemann- pick disease and urticaria pigmentosa.[18][19] Patents with neurofibromatosis 1 and JXG have a 20- to 32- fold higher risk of juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia (JMML) than patients with NF1 without JXG.[19] Due to this association, it has been suggested that patients with JXG and NF1 should be screened for the development of JMML. Common signs of JMML include anemia, thrombocytopenia, leukocytosis, lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly.

Incidence

JXG most commonly develops in infants younger than 2 years of age but has been found in older children.[1] In a cohort of 174 JXG patients with cutaneous lesions, the mean age was 3.3 years (median 1 year).[20] In a cohort of 30 patients with ocular JXG, the mean age at diagnosis was 4.3 years (median 1.3 years)2. 0.3%-10% of patients with cutaneous JXG were reported to have ocular involvement[10][21] with children under 2 years being at increased risk.[8] JXG has been reported to be more common in boys than in girls, with a male/female ratio ranging from 1.1:1 to 1.4:1.[22][23][24] However, in a cohort of 30 patients with ocular JXG, no gender predilection was shown.[2] A large literature review found a 0.75% rate of systemic manifestations in patients with cutaneous JXG.[25]

Diagnosis

A diagnosis of JXG is suspected in patients with characteristic yellowish cutaneous lesions. Excisional biopsy can be performed to confirm the diagnosis in cutaneous eyelid or conjunctival lesions. All patients with cutaneous JXG are advised to have a complete ophthalmic examination.[20] In cases of iris JXG, anterior segment optical coherence tomography can help confirm the diagnosis by demonstrating a thin, epi-iridic, flat mass.[26] Fine needle aspiration biopsy may be considered in cases that do not respond to corticosteroids or show an atypical presentation concerning for malignancy.[2][21]

The classic histopathologic findings include multinucleated Touton giant cells in addition to epitheloid histiocytes, lymphocytes and eosinophils (Figures 4-5). However, Touton giant cells are not mandatory for the diagnosis of JXG. In early JXG, small- to intermediate-sized mononuclear histiocytes display a compact sheet-like infiltrate; the lipidization of histiocytes is not detectable and Touton giant cells are rarely found. The pale eosinophilic cytoplasm is sparse to moderate and does often not contain any lipid vacuoles or only fine vacuoles.[24]

History

Adamson[27] first described JXG in 1905 in an infant with multiple cutaneous nodules, which he defined as congenital xanthoma multiplex. JXG and its distinct histopathological appearance became more widely recognized in 1954. In 1948, Fry first presented a case of JXG with iris involvement at the Ophthalmic Pathology Club meeting in Washington DC and the case was subsequently published by Blank et al. one year later.[28]

Differential Diagnosis

Eyelid JXG typically presents as a cutaneous yellowish nodule. The differential diagnosis for non-pigmented elevated eyelid lesions in children and young adults is wide and includes amelanotic nevus, syringoma, eccrine hidrocystoma, apocrine hidrocystoma, squamous papilloma, lipoma, molluscum and sarcoidosis. Conjunctival JXG must be differentiated from epibulbar dermoid or lipodermoid. Spontaneous hyphema is a common presenting sign of iris JXG. The differential diagnosis of hyphema in childhood includes neoplasm (retinoblastoma, medulloepithelioma, and leukemia), trauma, retinopathy of prematurity, and blood dyscrasias.[2]

Management

For eyelid JXG, excisional biopsy is commonly performed and is both diagnostic and therapeutic.[2] Alternatively, topical and intralesional corticosteroids have been used to treat eyelid lesions.[29] Topical corticosteroids have also shown success in the treatment of limbal JXG.[28] Observation alone is a reasonable option for characteristic lesions, as most cutaneous lesions stabilize or regress in one to five years.[8][9][10] In a case report of a newborn with extensive JXG involving the orbit, sinuses, brain and subtemporal fossa, management was limited to conservative observation.[6] For iris JXG, prompt treatment is recommended to prevent vision loss from recurrent hyphema, secondary glaucoma, and complications related to neovascularization. Corticosteroids are the mainstay for treatment of iris JXG. Samara et al. reported the use of topical high-dose corticosteroids with a slow taper lasting 3 to 4 months.[2] Periocular corticosteroid injection was considered when response to topical administration was poor or in case of concerns with compliance.[21] Systemic corticosteroid or low-dose ocular radiotherapy can be considered in recalcitrant cases.[21][30][31] Multimodal chemotherapy has been used in rare cases of extensive, systemic JXG.[24]

Prognosis

The prognosis for patients with JXG is generally good. The skin lesions usually regress (or at least stabilize) with time, and even large, deeply located tumors pursue a favorable course. Eyelid and conjunctiva JXG have a more benign course compared with JXG of the iris. Iris JXG can lead to vision loss due to recurrent hyphema, secondary glaucoma and neovascularization-related complications. Analysis of the clinical course of 129 patients who had undergone excisional biopsy showed that 83% of JXG patients did not have any recurrence, 10% experienced recurrence of the excised lesion, and 7% developed additional lesion(s) in the vicinity of the original tumor following excision.[24] Death has been reported in rare systemic JXG cases. Dehner documented two deaths among eight patients with systemic disease.[20] Unlike in LCH, parenchymal and systemic manifestations are rare in JXG, which explains the favorable overall prognosis.[24]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Juvenile Xanthogranuloma. In: Basic and clinical science course (BCSC) Section 6: Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. San Francisco, CA: American Academy of Ophthalmology; 2017

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 2.9 Samara WA, Khoo CT, Say EA, et al. Juvenile Xanthogranuloma Involving the Eye and Ocular Adnexa: Tumor Control, Visual Outcomes, and Globe Salvage in 30 Patients. Ophthalmology 2015;122(10):2130-8.

- ↑ DeBarge LR, Chan CC, Greenberg SC, et al. Chorioretinal, iris, and ciliary body infiltration by juvenile xanthogranuloma masquerading as uveitis. Surv Ophthalmol 1994;39(1):65-71.

- ↑ Wertz FD, Zimmerman LE, McKeown CA, et al. Juvenile xanthogranuloma of the optic nerve, disc, retina, and choroid. Ophthalmology 1982;89(12):1331-5.

- ↑ Hildebrand GD, Timms C, Thompson DA, et al. Juvenile xanthogranuloma with presumed involvement of the optic disc and retina. Arch Ophthalmol 2004;122(10):1551-5.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Johnson TE, Alabiad C, Wei L, Davis JA. Extensive juvenile xanthogranuloma involving the orbit, sinuses, brain, and subtemporal fossa in a newborn. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg 2010;26(2):133-4.

- ↑ Zimmerman LE. Ocular lesions of juvenile xanthogranuloma. Nevoxanthoedothelioma. Am J Ophthalmol 1965;60(6):1011-35

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 Cypel TK, Zuker RM. Juvenile xanthogranuloma: case report and review of the literature. Can J Plast Surg 2008;16(3):175-7.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Chaudhry IA, Al-Jishi Z, Shamsi FA, Riley F. Juvenile xanthogranuloma of the corneoscleral limbus: case report and review of the literature. Surv Ophthalmol 2004;49(6):608-14.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 Chang MW, Frieden IJ, Good W. The risk intraocular juvenile xanthogranuloma: survey of current practices and assessment of risk. J Am Acad Dermatol 1996;34(3):445-9.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Hernandez-Martin A, Baselga E, Drolet BA, Esterly NB. Juvenile xanthogranuloma. J Am Acad Dermatol 1997;36(3 Pt 1):355-67; quiz 68-9.

- ↑ Stover DG, Alapati S, Regueira O, et al. Treatment of juvenile xanthogranuloma. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2008;51(1):130-3.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Mori H, Nakamichi Y, Takahashi K. Multiple Juvenile Xanthogranuloma of the Eyelids. Ocul Oncol Pathol 2018;4(2):73-8

- ↑ Freyer DR, Kennedy R, Bostrom BC, et al. Juvenile xanthogranuloma: forms of systemic disease and their clinical implications. J Pediatr 1996;129(2):227-37.

- ↑ Orsey A, Paessler M, Lange BJ, Nichols KE. Central nervous system juvenile xanthogranuloma with malignant transformation. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2008;50(4):927-30.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Bellinato F, Maurelli M, Colato C, et al. BRAF V600E expression in juvenile xanthogranuloma occurring after Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Br J Dermatol 2019;180(4):933-4.

- ↑ Patrizi A, Neri I, Bianchi F, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis and juvenile xanthogranuloma. Two case reports. Dermatology 2004;209(1):57-61.

- ↑ Cambiaghi S, Restano L, Caputo R. Juvenile xanthogranuloma associated with neurofibromatosis 1: 14 patients without evidence of hematologic malignancies. Pediatr Dermatol 2004;21(2):97-101.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Zvulunov A, Barak Y, Metzker A. Juvenile xanthogranuloma, neurofibromatosis, and juvenile chronic myelogenous leukemia. World statistical analysis. Arch Dermatol 1995;131(8):904-8.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Dehner LP. Juvenile xanthogranulomas in the first two decades of life: a clinicopathologic study of 174 cases with cutaneous and extracutaneous manifestations. Am J Surg Pathol 2003;27(5):579-93.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 Karcioglu ZA, Mullaney PB. Diagnosis and management of iris juvenile xanthogranuloma. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus 1997;34(1):44-51.

- ↑ Nascimento AG. A clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical comparative study of cutaneous and intramuscular forms of juvenile xanthogranuloma. Am J Surg Pathol 1997;21(6):645-52.

- ↑ Sonoda T, Hashimoto H, Enjoji M. Juvenile xanthogranuloma. Clinicopathologic analysis and immunohistochemical study of 57 patients. Cancer 1985;56(9):2280-6.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 24.4 Janssen D, Harms D. Juvenile xanthogranuloma in childhood and adolescence: a clinicopathologic study of 129 patients from the kiel pediatric tumor registry. Am J Surg Pathol 2005;29(1):21-8.

- ↑ Samuelov L, Kinori M, Chamlin SL, et al. Risk of intraocular and other extracutaneous involvement in patients with cutaneous juvenile xanthogranuloma. Pediatr Dermatol 2018;35(3):329-35.

- ↑ Samara WA, Khoo CT, Magrath G, Shields CL. Multimodal imaging for detection of clinically inapparent diffuse iris juvenile xanthogranuloma. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus 2015;52 Online:e30-3.

- ↑ Adamson HG. A case of congenital xanthoma multiplex. Society intelligence. The Dermatological Society of London. Br J Dermatol 1905;17:222.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Blank H, Eglick PG, Beerman H. Nevoxantho-endothelioma with ocular involvement. Pediatrics 1949;4(3):349-54.

- ↑ Kuruvilla R, Escaravage GK, Jr., Finn AJ, Dutton JJ. Infiltrative subcutaneous juvenile xanthogranuloma of the eyelid in a neonate. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg 2009;25(4):330-2.

- ↑ Casteels I, Olver J, Malone M, Taylor D. Early treatment of juvenile xanthogranuloma of the iris with subconjunctival steroids. Br J Ophthalmol 1993;77(1):57-60.

- ↑ Cleasby GW. Nevoxanthoendothelioma (juvenile xanthogranuloma) of the iris. Diagnosis by biopsy and treatment with x-rays. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol 1961;65:609-13.