Cerebrotendinous Xanthomatosis (CTX)

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Introduction

Cerebrotendinous Xanthomatosis (CTX) is a rare and presumably underdiagnosed, autosomal recessive, metabolic storage disorder. CTX is caused by caused by mutations in the CYP27A1 gene, which encodes for a sterol 27-hydroxylase enzyme important in bile acid synthesis. At least 50 pathogenic mutations have been found in the CYP27A1 gene.[1][2] Sterol 27-hydroxylase deficiency leads to decreased synthesis of bile acid and excess 5-alpha-cholestanol accumulation in the blood and tissues of affected patients; this includes the brain, connective tissue, and the crystalline lens. The hallmark manifestations of CTX have a variable onset and severity, which may lead to delayed-diagnosis and under-diagnosis. Irreversible neurological deterioration is present in late disease.[3]

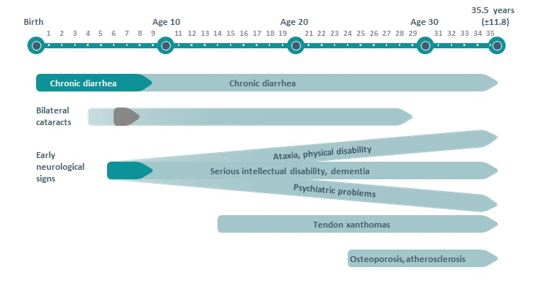

Eye care professionals are in a unique position to identify and diagnose CTX at a time when serious disability can be prevented.[4] The mean age of diagnosis is 35.5 years, therefore patients are often well into adulthood before receiving a diagnosis and may lose the window of opportunity to prevent irreversible neurologic damage.[5] If untreated, patients with CTX have a life expectancy into their 50s and 60s. However, treated they are expected to return to the average lifespan.[6]

Epidemiology

The prevalence of CTX in the US population is estimated to be as high as 3 to 5 per 100,000, predicting a minimum number of 8,400 affected individuals.[7] CTX is likely underdiagnosed with known patients in the US numbering less than 100. Approximately 425 cases have been reported worldwide. This disorder is more common in the Moroccan Jewish population with a reported incidence of 1 in 108, as well as being more commonly observed in women.[6][8][9][10][11]

Pathophysiology

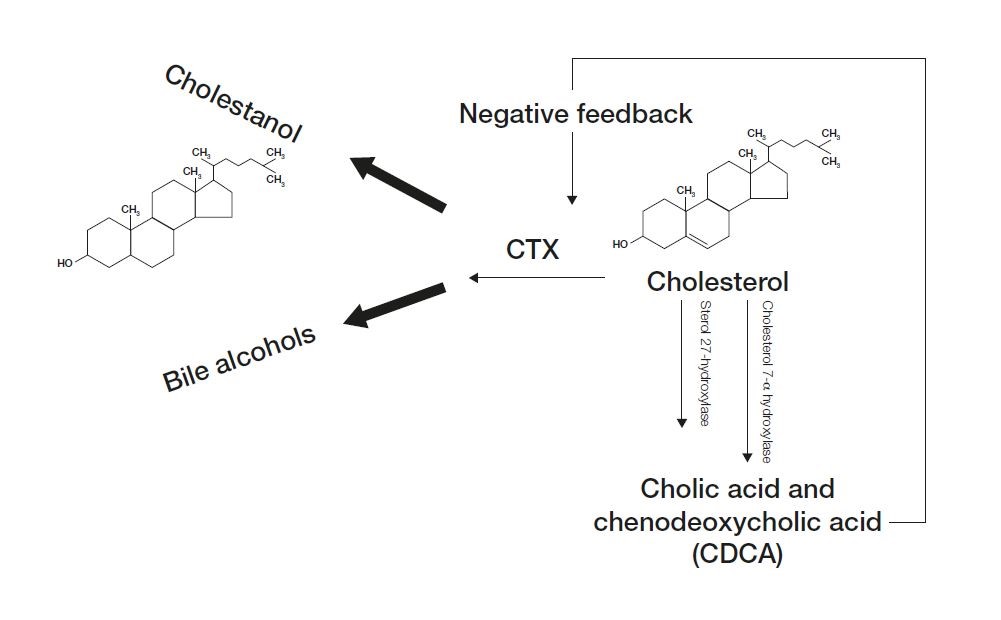

CTX is caused by a mutations in the CYP27A1 gene. This gene is responsible for producing an enzyme called sterol 27-hydroxylase. Under normal conditions, sterol 27-hydroxylase works in a pathway to break down cholesterol into bile acids necessary for the body to digest fats.[10]

Disease-causing mutations in the CYP27A1 gene lead to a deficiency in this enzyme, which decreases the body’s ability to break down cholesterol into a bile acid called chenodeoxycholic acid by preventing critical steps in bile acid synthesis.[2]

As chenodeoxycholic acid (a potent inhibitor of cholesterol 7-alpha-hydroxylase) is decreased, cholesterol cannot be properly excreted in the form of bile acids. These conditions lead to a significant increase in the levels of bile alcohols and levels of cholestanol, a byproduct of abnormal bile acid synthesis.[2] (Fig. 1)

These bile alcohols are excreted in bile, urine, and feces, but cholestanol accumulates, especially in the brain, peripheral nerves, lenses, bone and tendons, and causes the signs and symptoms of CTX.[6]

Clinical Characteristics

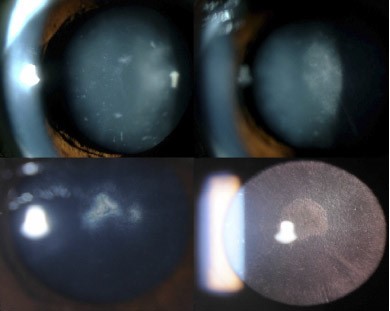

Typical clinical characteristics of CTX may include some combination of infantile-onset chronic diarrhea, bilateral cataracts with juvenile onset, tendon xanthomas, psychiatric and abnormal behavioral symptoms, and cognitive and other neurologic impairments. Clinical features are variable in severity and onset.[1] [13](Fig. 2)

In a report by Pagon RA et al in Cerebrotendinous Xanthomatosis GeneReviews®, the clinical features of 49 individuals diagnosed with CTX from 36 unrelated families were noted. Among the features reported, cataracts were present in 92% individuals, pyramidal signs were observed in 92%, cerebellar signs and peripheral neuropathy were noted in 82%, tendon xanthomas in 78%, cognitive impairment in 78%. In addition, psychiatric symptoms and behavioral changes in 73%, osteoporosis in 65%, diarrhea in 47%, and seizures in 24%.[4]

Ocular Clinical Manifestations

Bilateral cataracts, caused by cholestanol buildup in the crystalline lens, usually develop within the first 3 decades of life; often between the ages of 4 and 18 years of age.[14] This manifestation is almost a universal characteristic of CTX and often one of the first findings (first in 75% of individuals).[15] These patients develop irregular cortical opacities, anterior polar cataracts, or dense posterior subscapular cataracts.[14][16] Fleck lenticular deposits may be an early sign of CTX. (Fig. 3) The majority of patients will develop lenticular manifestations prior to significant neurological advancement.

Other ocular findings include [8][17][18][14][16]

- palpebral xanthelasmas

- optic nerve atrophy leading to afferent pupillary defect and possible central scotoma

- optic neuritis

- optic disc swelling

- proptosis, exophthalmos

- retinal vessel sclerosis

- cholesterol-like deposits along vascular arcades

- myelinated nerve fibers

Gastrointestinal Clinical Manifestations

Chronic diarrhea is often the first systemic manifestation of CTX. This may begin when the affected individual is still an infant.[1] An evaluation of an individual with a suspicion for CTX should include a direct inquiry as to a past medical history of unexplained bouts of diarrhea during the childhood period.[19]

Patients with CTX often have an increased incidence of prolonged unexplained neonatal cholestatic jaundice or intractable diarrhea.

Tendon Xanthomas

Tendon xanthomas, caused by cholestanol buildup in the tendons, usually appear late in the disease, commonly in the second or third decade. Most often these xanthomas occur on the Achilles tendons.[5] These xanthomas can also occur on the extensor tendons of the elbow and hand, patellar tendon, and neck tendons. Xanthomas have also been reported in the lung, bones, and central nervous system.[15][19]

The presence of tendon xanthomas in a patient with normal plasma cholesterol levels and normal lipoprotein profile should trigger an investigation of CTX as a potential underlying cause.[5] Additionally, high tissue and plasma cholestanol concentrations, decreased chenodeoxycholic acid, and increased bile alcohols help distinguish CTX.[15]

Neurologic Clinical Manifestations

Neurologic signs and symptoms of CTX usually appear after the second decade. Psychiatric manifestations or learning disabilities may appear earlier in the disease.[20] More than half of affected patients develop dementia, with deterioration of cognitive function starting in their 20s.[21][22] Pyramidal and cerebellar signs commonly develop in the second and third decades as well. [15]

Although not generally considered a hallmark manifestation, a significant amount of individuals with CTX have reported seizure activity. Peripheral neuropathy, mixed motor and sensory motor, and pes cavus are noted features. [12][22][23] Psychiatric symptoms such as behavioral changes, hallucinations, agitation, aggression, depression, and suicide attempts have been documented.[21] Lipid deposits and white matter loss in the brain has been reported in patients with advanced CTX.

Other Manifestations

Other less common findings include:[6] [5][23]

- Osteoporosis

- compression fractures

- premature atherosclerosis resulting in myocardial infarction

- cardiac autonomic dysfunction

- pulmonary insufficiency

- hypothyroidism

Differential Diagnosis

Familial hypercholesterolemia and other forms of autosomal dominant hypercholesterolemias are potential causes of tendon xanthomas. With familial hypercholesterolemia, however, laboratory testing typically shows increased levels of total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol, which are not features of CTX.[12]

Sitosterolemia is an inherited sterol storage disease characterized by tendon xanthomas and by strong predisposition to premature atherosclerosis. However, primary neurologic signs, diarrhea, and cataracts are not present in this disease.[12]

Smith-Lemli-Optiz syndrome (SLOS) has many signs and symptoms of CTX, including juvenile cataract and xanthomas. SLOS is an autosomal recessive disorder associated with mutations in DHCR7 gene that reduces or eliminates the activity of 7-dehydrocholesterol reductase. This enzyme is responsible for the final step of cholesterol production. These patients have learning and behavioral dysfunction, however these patients often present with microcephaly, hypotonia, and hearing/speech problems. Unlike CTX, those with SLOS have hypocholesterolemia.[4]

Marinesco-Sjogran syndrome has a similar presentation with congenital cataract and cerebellar ataxia but does not present with intractable diarrhea that can be characteristic of CTX.[5] Additionally, people with Marinesco-Sjogran syndrome tend to have a shorter stature with skeletal deformity and muscular hypotonia. [6]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of CTX is often delayed until the fourth decade of life even with symptoms presenting on average 16 years before diagnosis.[6] CTX should be suspected in patients with some combination of infantile onset diarrhea, juvenile onset bilateral cataracts, adolescent to young adult-onset tendon xanthoma, and adult-onset progressive neurologic dysfunction.[4]

Screening of children with bilateral juvenile cataracts has shown improved diagnosis of CTX. [24]

MRI studies of the brain are an important component of the diagnostic workup for CTX. It may show bilateral hyperintensity of the dentate nuclei and cerebral and cerebellar white matter. Other MRI findings may show signal alterations of the cerebral peduncle, corona radiate, and subcortical white matter.[20][21] It should be known, however, that a normal MRI does not rule out CTX.[15]

Biochemical testing can be performed which may show high plasma and tissue cholestanol concentration. The most common abnormality is an elevated serum plasma cholestanol 5-10x normal levels.[6] A normal to low plasma cholesterol concentration is seen. Markedly decreased formation of chenodeoxycholic acid from impaired primary bile acid synthesis, and increased concentration of bile alcohols and their glycoconjugates in bile, urine, and plasma are features.[10] Increased concentrations of cholestanol and apolipoprotein B in cerebrospinal fluid from changes in the blood-brain barrier can be seen.

Molecular testing for mutations in the CYP27A1 gene using sequence analysis or deletion/duplication analysis can be performed.[25] This is the gold standard for diagnosis due to significant variation in clinical presentation. Genetic molecular testing in symptomatic suspected patients and in presymptomatic family members should be considered in consultation with a Geneticist and/or Genetics Counselor. More than 50 mutations in the CYP27A1 gene have been reported to be associated with CTX. The most frequent mutations of the CYP27A1 gene are distributed from exons 1 to 8. The majority of mutations are amino acid substitutions; splice site mutations have also been reported.[25]

Enzyme assays for reduced activity of sterol 27-hydroxylase enzymatic activity can be performed as well.

There are proposed suspicion index tables that include family history, systemic symptoms, and neurologic factors that can be used to help aid in the diagnosis of CTX.[23] Patients with a high suspicion index score (> or =100) should have assessment of serum cholestanol concentrations. Those with high plasma cholestanol concentrations should proceed to CYP27A1 gene sequencing.[5]

There has been no suitable test to screen newborn dried bloodspots (DBS) for CTX, however development of a methodology to enable sensitive detection of ketosterol bile acid precursors that accumulate has been investigated and reported by DeBarber AE et al. In reports, Newborn DBS concentrations of this ketosterol (120–214 ng/ml) were about 10-fold higher than in unaffected newborn DBS (16.4 ± 6.0 ng/ml).[24]

Treatment

Treatment for CTX is available in the form of oral chenodeoxycholic acid (CDCA). Berginer VM et al.[1] published findings in 1984 showing that long-term treatment of CTX with chenodeoxycholic acid suppressed abnormal endogenous bile acid synthesis, lowered elevated plasma cholestanol levels, and exerted a beneficial effect on the course of neurologic diseases in the majority of the subjects they tested.

The Food and Drug Administration designated chenodeoxycholic acid as an orphan drug in 2007, but it has not been fully approved.

HMG-COA reductase inhibitors have been indicated in supportive treatment of CTX alongside CDCA, but use should be cautioned due to potential muscle damage. Cholic acid has also been shown in a few individuals to help decrease cholestanol levels and improve neurologic symptoms.[15]

Symptomatic treatment is also important for other symptoms such as epilepsy, spasticity, and parkinsonism symptoms, as well as cataract removal.[15]

Treatment of CTX in the preclinical stage can reportedly prevent the onset of disease complications.[1] Because of this, the value of an early diagnosis for CTX is extremely important.

Additional Resources

Cerebrotendinous Xanthomatosis

- About CTX.com

- ClinicalTrials.gov

- CTXinfo.org(Patient/Caregiver website)

- Disease InfoSearch

- GeneReviews®

- Cholestanol storage disease - Genetic Testing Registry

- Genetics Home Reference

- National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD)

- OMIM/#213700 CEREBROTENDINOUS XANTHOMATOSIS; CTX

- Orphanet

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Berginer VM, et al. Chronic diarrhea and juvenile cataracts: think cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis and treat. Pediatrics. 2009;123:143-147.

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 2.2 Gallus GN, et al. Clinical and molecular diagnosis of cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis with a review of the mutations in the CYP27A1 gene. Neurol Sci. 2006;27:143-149.

- ↑ Patni N, Wilson DP. Cerebrotendinous Xanthomatosis. 2023 Mar 8. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, Boyce A, Chrousos G, Corpas E, de Herder WW, Dhatariya K, Dungan K, Hofland J, Kalra S, Kaltsas G, Kapoor N, Koch C, Kopp P, Korbonits M, Kovacs CS, Kuohung W, Laferrère B, Levy M, McGee EA, McLachlan R, New M, Purnell J, Sahay R, Shah AS, Singer F, Sperling MA, Stratakis CA, Trence DL, Wilson DP, editors. Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2000–2025. PMID: 27809439.

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Khan AO, Bock CJ. Ophthalmologist and Cerebrotendinous Xanthomatosis (CTX): Making the Diagnosis. Retrophin, Inc. Http://ctxinfo.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Ophthalmologists-and-CTX-Making-the-Diagnosis.pdf.

- ↑ Jump up to: 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Mignarri A, et al. A suspicion index for early diagnosis and treatment of cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2014 May;37(3):421-9

- ↑ Jump up to: 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 Carson BE, De Jesus O. Cerebrotendinous Xanthomatosis. 2023 Aug 23. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan–. PMID: 33232000.

- ↑ Monson DM, DeBarber AE, Bock CJ, Anadiotis G, Merkens LS, Steiner RD, Stout AU. Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis: a treatable disease with juvenile cataracts as a presenting sign. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011 Aug;129(8):1087-8. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2011.219. PMID: 21825196; PMCID: PMC3366103.

- ↑ Jump up to: 8.0 8.1 Salen G, Steiner RD. Epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment of cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis (CTX). J Inherit Metab Dis. 2017 Nov;40(6):771-781. doi: 10.1007/s10545-017-0093-8. Epub 2017 Oct 4. PMID: 28980151.

- ↑ Berginer VM, Abeliovich D. Genetics of cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis (CTX): an autosomal recessive trait with high gene frequency in Sephardim of Moroccan origin. Am J Med Gen. 1981;10:151-157.

- ↑ Jump up to: 10.0 10.1 10.2 Leitersdorf E et al. Frameshift and splice-junction mutations in the sterol 27-hydroxylase gene cause cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis in Jews of Moroccan origin. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:2488–96.

- ↑ Reshef A, Meiner V, Berginer VM, Leitersdorf E. Molecular genetics of cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis in Jews of north African origin. J Lipid Res. 1994 Mar;35(3):478-83. PMID: 8014582.

- ↑ Jump up to: 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Moghadasian MH. Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis: clinical course, genotypes and metabolic backgrounds. Clin Invest Med. 2004 Feb;27(1):42-50. PMID: 15061585.

- ↑ Verrips A, et al. Clinical and molecular genetic characteristics of patients with cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis. Brain. 2000;123:908-919.

- ↑ Jump up to: 14.0 14.1 14.2 Dotti MT, Rufa A, Federico A. Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis: heterogeneity of clinical phenotype with evidence of previously undescribed ophthalmological findings. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2001;24:696-706.

- ↑ Jump up to: 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 15.6 Federico A, Dotti MT, Gallus GN. Cerebrotendinous Xanthomatosis. 2003 Jul 16 [Updated 2013 Aug 1]. In: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Ardinger HH, et al., editors. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2016. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1409/

- ↑ Jump up to: 16.0 16.1 16.2 Khan, Arif O. et al. "Juvenile Cataract Morphology in 3 Siblings Not Yet Diagnosed with Cerebrotendinous Xanthomatosis." Ophthalmology120.5 (2013): 956-60. Web.

- ↑ Cruysberg JR. Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis: juvenile cataract and chronic diarrhea before the onset of neurologic disease. Arch Neurol. 2002;59:1975.

- ↑ Miyamoto M, Ishii N, Mochizuki H, Shiomi K, Kaida T, Chuman H, Nakazato M. Optic Neuropathy with Features Suggestive of Optic Neuritis in Cerebrotendinous Xanthomatosis. Case Rep Neurol Med. 2019 Feb 12;2019:2576826. doi: 10.1155/2019/2576826. PMID: 30891321; PMCID: PMC6390236.

- ↑ Jump up to: 19.0 19.1 Retrophin, Inc. aboutCTX.com. Retrieved Jan 29, 2024 from https://aboutctx.com/signs-symptoms

- ↑ Jump up to: 20.0 20.1 Lorincz MT, et al. Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis: possible higher prevalence than previously recognized. Arch Neurol. 2005;62:1459-1463.

- ↑ Jump up to: 21.0 21.1 21.2 Fraidakis MJ. Psychiatric manifestations in cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis.Translational Psychiatry. 2013 Sep 3;3:e302

- ↑ Jump up to: 22.0 22.1 Rafiq M, Sharrack N, Shaw PJ, Hadjivassiliou M. A neurological rarity not to be missed: cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis. Pract Neurol. 2011 Oct;11(5):296-300. doi: 10.1136/practneurol-2011-000003. PMID: 21921005.

- ↑ Jump up to: 23.0 23.1 23.2 Nóbrega PR, Bernardes AM, Ribeiro RM, Vasconcelos SC, Araújo DABS, Gama VCV, Fussiger H, Santos CF, Dias DA, Pessoa ALS, Pinto WBVR, Saute JAM, de Souza PVS, Braga-Neto P. Cerebrotendinous Xanthomatosis: A practice review of pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Front Neurol. 2022 Dec 23;13:1049850. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.1049850. PMID: 36619921; PMCID: PMC9816572.

- ↑ Jump up to: 24.0 24.1 DeBarber AE, Duell PB. Update on cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2021 Apr 1;32(2):123-131. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0000000000000740. PMID: 33630770.

- ↑ Jump up to: 25.0 25.1 Mi-Hye Lee et al., Fine-mapping, mutation analyses, and structural mapping of cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis in U.S. pedigrees. February 2001 The Journal of Lipid Research, 42, 159-169.