Methamphetamine-Induced Keratitis

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Disease

Methamphetamine (MA) is a potent neurostimulant classified as a Schedule II controlled substance in the United States[1]. While it can be utilized in psychiatry for treating attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and narcolepsy, it is more commonly abused as a recreational drug due to the intense euphoria it can induce, lasting up to 24 hours[2].

First identified by Poulsen et al. in 1996, methamphetamine-induced keratitis (MIK) is an important side effect of MA[3]. Given the rise in MA abuse over the past two decades and its potentially devastating impact on vision, eye care providers must be knowledgeable about the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of MIK.

Epidemiology

MIK is a possible side effect of MA use and has been described in several case reports since the 1990s. MA is currently the most common illicit drug according to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime[4]. In 1998, the prevalence of MA use in the United States was approximately 2.1%, and this has steadily increased since then[5]. The amount of MA seized worldwide quadrupled between 2013 and 2022[4].

The primary age group of MA abusers ranges from 15 and 64 years old. Psychiatric disorders, peer influence or pressure, curiosity and adventurous tendency have been identified as significant risk factors for initiation of MA[6][7]. The predominant methods of MA use are inhalation and sniffing, followed by swallowing, cooking, injecting and smoking[8].

General Pathology

MIK is primarily caused by the toxic effects of MA on the cornea. Most patients with MIK present with significant vision loss due to corneal ulcers, which in nearly all reported cases are linked to infectious keratitis. This association makes it challenging to distinguish whether the primary cause of corneal damage is MIK or an infectious origin. However, MIK typically exhibits more neurotrophic features than standard infectious keratitis.

The corneal ulcers in MIK are often advanced, characterized by large infiltrates, stromal necrosis, and severe thinning. In many cases, rapid corneal melting and perforation can occur despite aggressive topical treatment with fortified antibiotics, necessitating interventions like glue or therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty.

Histological pathology of excised cornea in severe MIK could reveal absence of epithelium, stromal inflammation at various stages, tissue loss, descematocele, and a mix of microorganisms with special stains[3][9][10][11].

Pathophysiology

There are multiple possible contributory causes of methamphetamine-induced keratitis. These causes were originally categorized and postulated by Poulsen et al, with subsequent additional hypotheses relating to the pathophysiology of MIK[9][12][10][13][14]:

- Direct pharmacologic and physical effects of MA

- MA acts as a vasoconstrictor, potentially leading to vasculitis and reduced ocular perfusion.

- A heightened pain threshold can impair the blink reflex, increasing the risk of corneal epithelial injury.

- Dopamine and serotonin dysregulation associated with MA use can lead to corneal nerve damage secondary to neurotrophic keratitis.

- Toxic effects of diluting agents and by-products (ex: lidocaine, procaine, quinine, bicarbonate, strychnine, etc.)

- These agents can lead to ulceration and alkaline burns to corneal tissue.

- Manufacturing by-products or contaminants can lead to inadvertent caustic exposure.

- Effects related to the route of drug administration (intravenous, inhalation, smoking)

- Smoking can lead to chemical or thermal burns and tissue damage.

- MA is often sold as a hydrochloride salt, which may cause corneal damage from direct contact or exposure to fumes.

- Hand to eye exposure can also exacerbate corneal injury

- Psychological, mental, and behavioral effects of MA use

- The hyperactivity and obsessive behaviors induced by MA can result in repetitive eye rubbing or scratching, exacerbating ocular damage

- Excessive preoccupation with MA use and resulting cognitive deficits can lead to poor ocular hygiene

Primary prevention

Since MIK can be vision threatening, primary prevention should emphasize stopping initial use of MA. This can be done through various educational initiatives and community activities. In patients who continue to use MA, harm reduction approaches include educating patients on hand and dental hygiene and decreasing eye rubbing frequency.

Diagnosis

MIK is largely a clinical diagnosis. A diagnosis of methamphetamine-induced keratitis should include a detailed history and a complete ophthalmic examination.

History

When evaluating a patient with suspected methamphetamine-induced keratitis, obtaining a comprehensive history is crucial.

A detailed substance abuse history as part of the social history is the most important piece of information and should never be overlooked. The frequency and route of administration should be documented.

In addition, physicians should routinely inquire about the onset and characteristics of symptoms, focusing on any recent eye trauma or behaviors that increase the risk for keratitis. Patients should be asked about contact lens use, including the type of lenses, duration of wear, hygiene and their cleaning regimen. Poor contact lens hygiene can further compound the risk of infection. The ocular history should cover any previous episodes of similar symptoms, past eye diseases such as bacterial or viral keratitis, or prior eye surgeries including laser refractive surgery.

It is also important to crosscheck all current medications and eye drops, note any allergies, and gather relevant family history. As biologics are increasingly used to treat various diseases from atopic dermatitis to malignancy, ophthalmologists should be aware of their ocular side effects, especially severe keratoconjunctivitis that can mimic infectious keratitis and MIK.

Since MA use can have serious systemic effects such as multi-system damages, frequent respiratory illnesses, epilepsy, tooth or fingernail decay, a thorough review of system is essential.

Symptoms

The typical symptoms are:

- Decreased vision

- Foreign body sensation

- Redness

- Ocular pain or decreased sensation

- Tearing

- Itching

- Photophobia

Physical examination

Examination should include an assessment of visual acuity, intraocular pressure, pupil reactions, and a thorough slit-lamp examination. It is also important to test corneal sensation, as reduced sensation can be a sign of neurotrophic keratopathy, which is a common complication of MA use.

Proper eyelid closure, as well as an examination of the eyelids, lashes, and nasolacrimal system should be conducted to identify additional risk factors for infection. Fluorescein staining and assessment of corneal infiltrate location, shape, dimensions, and appearance should be examined. Examination for corneal neovascularization as well as corneal sensation should also be conducted. Corneal sensation can be assessed either with a cotton tip applicator or with an esthesiometer. Additionally, any anterior chamber reaction, such as the presence of cells, flare, fibrin, or hypopyon, should be noted.

A dilated fundus exam is also crucial to rule out vision-threatening posterior pole involvement, as MA use has been reported to cause retinal vascular occlusion, vasculitis, crystalline retinopathy and non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy[15][16][17][18][19]. If visualization of the posterior pole is not possible, B-scan ultrasonography should be performed to rule out additional posterior segment pathology, such as vitritis or endophthalmitis. Since MIK can affect both eyes, a thorough examination of both eyes is mandatory.

Signs

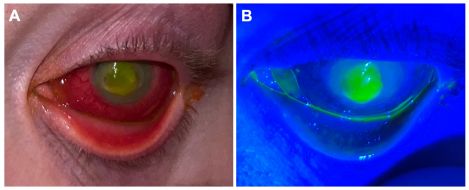

When MIK is mild (Figure 2), slit lamp examination may reveal:

- Eyelid edema

- Clear or purulent discharge

- Conjunctival injection

- Absence of corneal sensation

- Corneal epithelial defect

- Corneal stromal infiltrate

- Hypopyon

In advanced stage (Figures 3 and 4), clinicians should document these findings:

- Stromal necrosis

- Corneal thinning

- Descematocele

- Perforation with positive Seidel sign

- Vitritis/endophthalmitis

It is important to note that the exam findings overlap between MIK and infectious keratitis, as these two accompany in most cases.

Clinical diagnosis

A diagnosis is based largely on examination findings in conjunction with history of methamphetamine use. Anterior segment optical coherence topography (AS-OCT) can be used to evaluate the extent of corneal thinning.

Laboratory test

First, a urine toxicology test must be conducted to confirm substance use. Corneal scraping and culture should be performed promptly. Samples should be assessed for bacteria, fungi, HSV/VZV and Acanthemoeba using various agar plates and PCR/sequencing techniques. Additionally, swabbing of the fingernails for cultures may also aid in diagnosis and antibiotic selection.

Finally, keratolysis associated with rheumatoid arthritis and other immune-mediated keratitis must be ruled out. Clinicians should obtain a lab panel consisting of complete blood count, complete metabolic profile, urinalysis, rheumatoid factor (RF), anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody (anti-CCP) anti-nuclear antibody (ANA), and anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA). Masquerades such as syphilis, TB, and sarcoidosis should also be excluded through laboratory testing.

Differential diagnosis

- Infectious keratitis

- Exposure/neurotrophic keratopathy

- Topical anesthetic abuse keratopathy

- Immune-mediated keratitis

- Medication-induced keratitis (in particular biologics)

- Vitamin A deficiency

Management

General treatment

Topical antibiotics should be initiated promptly. Patients need close follow up and should be strictly advised to avoid eye rubbing. Compliance with frequent eye drop administration should be assessed, and patients should be recommended for admission if support is needed for antibiotic drop administration, or if the infection is sight threatening or on the verge of perforation.

Medical therapy

Antibiotic coverage and frequency are guided by the size and extent of corneal damage. In cases of severe keratitis, characterized by an infiltrate larger than 1.5mm or located within the visual axis, patients are usually started on broad spectrum antibiotics such as fortified vancomycin and fortified tobramycin every hour. For moderate cases, a fourth-generation fluoroquinolone drop such as moxifloxacin can be used hourly. For mild cases, treatment may begin with topical fluoroquinolone or polymyxin B/trimethoprim drops every 2 to 4 hours. Antivirals can be considered if there is suspicion of herpetic disease. Finally, it is essential to tailor antibiotic choice based on the culture and sensitivity results. For example, if cultures reveal a fungal species, topical and/or systemic antifungal should be added to the treatment regimen.

Topical steroids should be considered when the infection has been properly controlled and after ruling out atypical etiologies such as fungal or acanthamoebic infection. This helps to reduce inflammation and prevent complications like synechiae, while ensuring that the underlying infection does not worsen. Careful monitoring is essential to ensure patient safety during this phase of treatment.

Oral vitamin C and tetracyclines can be given to help reduce collagenolysis and keratolysis.

If corneal thinning is present, the eye should be protected with a shield. A pressure patch should not be placed.

Medical follow up

Daily follow up is required initially. As above, antibiotic coverage should be adapted based on sensitivities and clinical response. Once a positive response is noted based on clinical examination and improvement of symptoms, the antibiotic regimen can be gradually reduced.

Surgery

If corneal perforation occurs or there is descematocele with impending perforation, immediate intervention is critical. For small defect, cyanoacrylate tissue glue and a bandage contact may be adequate initially. For larger defect, a patch graft or therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty may be necessary to restore the globe integrity and prevent endophthalmitis. If surgery is conducted, the corneal specimen can be sent for pathology for further evaluation.

Surgical follow up

Close postoperative follow up is warranted.

Prognosis

Due to the complexity of keratitis and the presence of behavorial/psychological co-morbidities, the prognosis is often guarded. Close follow-up and multi-disciplinary approaches are essential to prevent complications and improve final outcomes.

References

- ↑ Cisneros IE, Ghorpade A. Methamphetamine and HIV-1-induced neurotoxicity: role of trace amine associated receptor 1 cAMP signaling in astrocytes. Neuropharmacology. 2014 Oct;85:499-507.

- ↑ Radfar SR, Rawson RA. Current research on methamphetamine: epidemiology, medical and psychiatric effects, treatment, and harm reduction efforts. Addict Health. 2014 Summer-Autumn;6(3-4):146-54.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Poulsen, Eric J. M.D.; Mannis, Mark J. M.D.; Chang, Steven D. M.D.. Keratitis in Methamphetamine Abusers. Cornea 15(5):p 477-482, September 1996.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 UNODC, World Drug Report 2024. United Nations publication, 2024.

- ↑ Anglin MD, Burke C, Perrochet B, Stamper E, Dawud-Noursi S. History of the methamphetamine problem. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2000 Apr-Jun;32(2):137-41.

- ↑ Obadeji A, Kumolalo BF, Oluwole LO, et al. Substance use among adolescent high school students in Nigeria and its relationship with psychosocial factors. J Res Health Sci. 2020;20(2):e00480.

- ↑ WHO. Mental health of adolescents. WHO, 2021.

- ↑ Obande-Ogbuinya NE, Aleke CO, Omaka-Amari LN, Ifeoma UMB, Anyigor-Ogah SC, Mong EU, Afoke EN, Nnaji TN, Nwankwo O, Okeke IM, Nnubia AO, Ibe UC, Ochiaka RE, Ngwakwe PC, Item O, Nwafor KA, Nweke IC, Obasi AF. Prevalence of Methamphetamine (Mkpurummiri) use in south east Nigeria: a community-based cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2024 Sep 7;24(1):2436

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Franco J, Bennett A, Patel P, Waldrop W, McCulley J. Methamphetamine-Induced Keratitis Case Series. Cornea. 2022;41(3):367-369.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Kroll M, Affeldt JC, Meallet M. Methamphetamine keratitis as a variant of neurotrophic ocular surface disease. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:103

- ↑ Chuck RS, Williams JM, Goldberg MA, Lubniewski AJ. Recurrent corneal ulcerations associated with smokeable methamphetamine abuse. Am J Ophthalmol. 1996 May;121(5):571-2.

- ↑ Fowler AH, Majithia V. Ultimate mimicry: methamphetamine-induced pseudovasculitis. Am J Med. 2015;128:364–366.

- ↑ Movahedan A, Genereux BM, Darvish-Zargar M, et al. Long-term management of severe ocular surface injury due to methamphetamine production accidents. Cornea. 2015;34:433–437.

- ↑ Huang Y, Nguyen NV, Mammo DA, Albini TA, Hayek BR, Timperley BD, Krueger RR, Yeh S. Vision health perspectives on Breaking Bad: Ophthalmic sequelae of methamphetamine use disorder. Front Toxicol. 2023 Mar 8;5:1135792.

- ↑ Shaw H. E., Jr., Lawson J. G., Stulting R. D. (1985). Amaurosis fugax and retinal vasculitis associated with methamphetamine inhalation. J. Clin. Neuroophthalmol. 5 (3), 169–176.

- ↑ Wallace R. T., Brown G. C., Benson W., Sivalingham A. (1992). Sudden retinal manifestations of intranasal cocaine and methamphetamine abuse. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 114 (2), 158–160.

- ↑ Hazin R., Cadet J. L., Kahook M. Y., Saed D. (2009). Ocular manifestations of crystal methamphetamine use. Neurotox. Res. 15 (2), 187–191.

- ↑ Guo J., Tang W., Liu W., Zhang Y., Wang L., Wang W. (2019). Bilateral methamphetamine-induced ischemic retinopathy. Am. J. Ophthalmol. Case Rep. 15, 100473.

- ↑ Wijaya J., Salu P., Leblanc A., Bervoets S. (1999). Acute unilateral visual loss due to a single intranasal methamphetamine abuse. Bull. Soc. Belge. Ophtalmol. 271, 19–25.