Herpes Simplex Epithelial Keratitis

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) is a very common, lifelong infection that often is asymptomatic. However, HSV can result in significant eye disease and is the most common cause of corneal blindness in the United States (US).[1]

This EyeWiki article will focus on the corneal epithelial manifestations of HSV. Descriptions of the HSV stromal and endothelial manifestations can be found here.

Disease

Herpetic keratitis can be unilateral or, more rarely, bilateral. The latter being more common in patients with atopy due to proposed immune dysregulation increasing susceptibility to viral infections.[2] The incidence of bilateral involvement range from 1.3% to 12%.[3] HSV can affect all layers of the cornea, and may be accompanied by a blepharoconjunctivitis, which may result in lesions of the eyelids and a follicular conjunctivitis. Characteristically, HSV epithelial keratitis presents with classic dendritic lesions with terminal bulbs. Recurrent activations within the sensory ganglion can result in cornea scarring, necrosis, and decreased corneal sensation (neurotrophic cornea), all of which can be vision threatening.

Epidemiology

HSV keratitis is a leading cause of corneal blindness worldwide.[4]

Age, geographic location, and socioeconomic status appear to affect the prevalence of disease.[5]

In the 2015-2016 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, the prevalence of HSV type 1 (HSV-1) was 47.8% and HSV type 2 (HSV-2) was 11.9%. [6] Globally, the incidence of HSV keratitis is 1.5 million yearly, including 40,000 new cases that result in severe visual impairment. [7] In the US, approximately 500,000 people are afflicted with ocular HSV.[7]

Worldwide, approximately one million people suffer from HSV epithelial keratitis yearly.[7] Several large scale studies have demonstrated that epithelial keratitis is the most common form of HSV ocular involvement.[8][9]

Etiology

HSV keratitis is caused by the herpes simplex virus, a double- stranded DNA virus made up of an icosahedral shaped capsid surrounding a core of DNA and phosphoproteins of viral chromatin.[10] HSV- I and HSV- II are differentiated by virus specific antigens. HSV- I typically affects the orofacial region, whereas HSV- II usually causes genital infections. However, studies have shown that both viruses may affect either location, and mixed infections have been reported.[11]

Risk Factors

Risk factors for development of primary HSV involve direct contact with infected secretions or lesions.[10]

Risk factors for reactivation of disease have been postulated to include:[12][13]

- Sunlight

- Fever

- Trauma

- Heat

- Menstruation

- Stress

- Trigeminal nerve manipulation

- Infectious disease and immunocompromised states.

- COVID-19 infection[14]

- COVID-19 vaccination[15]

General Pathology

Corneal scrapings of HSV keratitis prepared with Giemsa stain may reveal the presence of intranuclear viral inclusion bodies.[16] Multinucleated giant cells may also be found.

Pathophysiology

The only hosts for HSV are humans.[11] Ocular herpetic disease is more frequently caused by HSV- I, which is presumed to gain access to the cornea via the trigeminal nerve from an oral infection or direct contact of infected secretions.[13] Initial infection typically remains asymptomatic, but patients may present with an acute follicular conjunctivitis and an upper respiratory infection. After the primary infection, the virus travels via sensory nerve axons to establish a latent infection in the trigeminal ganglion where it resides permanently. The virus is then capable of reactivation along any branch of the trigeminal nerve to cause ocular morbidity.[13] HSV epithelial keratitis may occur during the primary and/or recurrent infection.[11]

Primary Prevention

Prevention of herpetic infection includes avoidance of direct contact with lesions and secretions of a patient with active HSV.

Diagnosis

History

Key aspects to inquire about in the history of patients with suspected HSV include past infections (history of recurrent "red eye", particularly unilateral), underlying systemic diseases, immunosuppression or immunocompromised state, history of eyelid lesions, history of oral and genital ulcers, and recent infections and vaccinations.

Physical examination

In addition to a standard biomicroscopy, special attention should be paid to the presence of a preauricular lymph node, vesicular lesions on the lids or adnexa, bulbar follicles, decreased corneal sensation, and most notably the presence of epithelial dendrites on the cornea.

For primary HSV keratitis, it is more common for patients to present with a blepharoconjunctivitis than with cornea involvement. Primary keratitis typically occurs in childhood and is spread by direct contact.[11] Diffuse punctate keratopathy or corneal microcysts may be visible.[17]

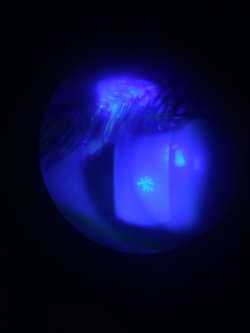

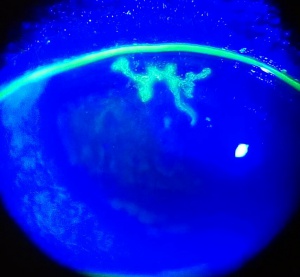

Recurrent HSV keratitis can also present as epithelial keratitis. The earliest sign of epithelial disease include raised clear vesicles that later coalesce to form the classic dendritic lesion. The dendritic ulcer, the dichotomous branching cornea lesion, can be stained with fluorescein and is the hallmark of HSV epithelial keratitis. These epithelial lesions represent active replicating virus. As the dendritic ulcer may evolve into a geographic ulceration of the cornea, especially in patients with compromised immunity, atopy, or on topical steroids.

Signs

The hallmark of HSV keratitis is the presence of multiple small branching epithelial dendrites on the surface of the cornea. Although often times it first presents as a coarse, punctuate epithelial keratitis, which may be mistaken for a viral keratitis. The HSV dendrite possesses terminal bulbs that distinguish it from the herpes zoster pseudodendrite and follows the nerve pattern of the cornea.

Symptoms

Typically, patients with acute HSV keratitis present with blurred vision, photophobia, pain, redness, and/or tearing. Ocular pain is often a hallmark of HSV epithelial keratitis, as it tends to be the most painful form of HSV keratitis.[11]

Clinical diagnosis

The clinical diagnosis of HSV may be suggested by the presence of the multiple arborizing dendritic epithelial ulcers with terminal bulbs. The bed of the ulcer stains with fluorescein, while the swollen corneal epithelium at the edge of the ulcer typically stains with rose bengal. Several dendrites may also coalesce to form a geographic epithelial ulcer.[18] In addition, there may be mild conjunctival injection, ciliary flush, mild stromal edema and subepithelial white blood cell infiltration. Following resolution of the primary infection, a "ghost dendrite" may be visible just beneath the prior area of epithelial ulceration.

Diagnostic procedures

The diagnosis of HSV is often made clinically, however, laboratory tests are available to confirm the diagnosis in more ambiguous and difficult cases (and in all cases of neonatal herpetic infections). Serologic testing may be performed but is usually not helpful in recurrent disease as most adults are laterally infected with HSV. Thus, serum antibody testing is typically of limited use. However, conjunctival scrapings, impression cytology specimens, and scrapings from vesicular lesions on the skin may be tested by cytology, culture, or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for the presence of HSV.[16] Fluorescent antibody (FAB) testing involving impression cytology using nitrocellulose membrane or a cornea smear. A Tzanck smear can reveal multinucleated giant cells and intranuclear eosinophilic inclusion bodies.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnoses of HSV include herpes zoster ophthalmicus and other types of viral keratitis (adenovirus, cytomegalovirus, Epstein- Barr virus), neurotrophic keratopathy, epithelial regeneration line, iatrogenic (topical drops such as antivirals), acanthamoeba keratitis, soft contact lens overwear, microbial keratitis, staphylococcal marginal keratitis, and Thygeson’s superficial punctuate keratitis.[13]

Management

Primary HSV epithelial keratitis usually resolves spontaneously; however, treatment with antiviral medication does indeed shorten the course of the disease and may therefore reduce the long- term complications of HSV.[19]

General treatment

The mainstay of therapy is antiviral treatment either in the form of oral administration of acyclovir or valacyclovir or famciclovir for 10 to 14 days and/or topical antiviral medications.[20] Topical ganciclovir 0.15% (Bausch and Lomb Inc., Rochester, New York, USA) can be utilized and is approved by the FDA for the treatment of acute herpetic keratitis since 2009. It is typically dosed five times a day until the cornea ulcer heals, and then three times a day for another week. Topical therapy with trifluridine 1% eight to nine times a day can also be prescribed, but care must be taken to ensure antiviral drops are discontinued within 10-14 days due to significant corneal toxicity. Topical acyclovir is not approved by the FDA, but used commonly outside the United States for the treatment of HSV epithelial keratitis. Topical steroids are contraindicated in the presence of active epithelial disease, although cycloplegia drops and topical antibiotics may be added.[13]

Epithelial debridement of the dendrites may also be utilized in conjunction with antiviral therapy to help reduce viral load. Amniotic membrane may promote epithelial healing and reduce scar formation in conjunction with antivirals.[21] According to the landmark Herpetic Eye Disease Study (HEDS) published in 1991, long- term prophylaxis with oral antivirals decreases the risk of recurrent HSV keratitis.[22] Specifically, long- term acyclovir therapy (400mg twice a day for 1 year) decreased the risk of epithelial and stromal HSV disease by almost half. [23]

Medical follow up

The patient should be closely monitored and if no response to treatment occurs after one week of therapy, the possibility of resistance to antiviral therapy, antiviral toxicity, neurotrophic disease, poor compliance with medication, and/or an alternative diagnosis should be considered.

Surgery

If there is visually significant stromal scarring, a penetrating keratoplasty may be performed once the disease is quiescent. Depending on the location and size of the scar, a lamellar keratoplasty may also be used to clear the visual axis. Of note, in eyes that are unable to sustain a clear graft, a Boston keratoprosthesis may be a viable option.

Surgical follow up

Follow-up should be performed as standard of practice for penetrating keratoplasty.[24] Special attention should be paid to signs of recurrence of herpetic disease. Oral antiviral therapy may improve the rate of graft survival by decreasing the number of recurrences.

Complications

Corneal complications of herpetic eye disease range from epitheliopathy to frank neurotrophic or metaherpetic ulcers. Neurotrophic corneas, defined as corneas with decreased sensation due to corneal nerve changes after infection, can cause a wide array of issues ranging from severe dry eyes to corneal perforation from a non- healing neurotrophic ulcer.

Prognosis

Prognosis is usually good but greatly varies depending on severity and number of recurrences of the disease.

Additional Resources

Region Specific Information (from the AAO's Global Ophthalmology Guide):

Other resources:

- AAO Basic and Clinical Science Course, External Disease and Cornea, 2005-2006, 134-145.

- AAO Basic and Clinical Science Course, Ophthalmic Pathology and Intraocular tumors, 2005-2006, 65-66.

- Agarwal, A, Handbook of Ophthalmology, 2006, Slack Inc, 279-281.

- Krachmer J, Mannis M, Holland E: CORNEA, 2nd ed.Elsevier Mosby, 2005, 1043-1074.

- Porter D, Jimenez EM. Herpes Keratitis. American Academy of Ophthalmology. EyeSmart/Eye health. https://www.aao.org/eye-health/diseases/herpes-keratitis-list. Accessed February 15, 2023.

- Rapuano C, Heng W, Cornea, Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Ophthalmology, Wills Eye Hospital, 2003 159-170.

References

- ↑ Sudesh, S. & Laibson, P.R. The impact of the herpetic eye disease studies on the management of herpes simplex virus ocular infections. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 10, 230-233 (1999)

- ↑ Borkar DS, Gonzales JA, Tham VM, et al. Association between atopy and herpetic eye disease: results from the pacific ocular inflammation study. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014;132(3):326-331.

- ↑ Agarwal R., Maharana P.K., Titiyal J.S., Sharma N. Bilateral Herpes Simplex Keratitis: Lactation a Trigger for Recurrence! BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12:e223713. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2017-223713.

- ↑ Remeijer L., Maertzdorf J., Buitenwerf J., Osterhaus A.D.M.E., Verjans G.M.G.M. Corneal Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 Superinfection in Patients with Recrudescent Herpetic Keratitis. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2002;43:358–363.

- ↑ Wilhelmus KR, Dawson CR, Barron BA, et al. Risk factors for herpes simplex virus epithelial keratitis recurring during treatment of stromal keratitis or iridocyclitis. Herpetic Eye Disease Study Group. Br J Ophthalmol. 1996;80(11):969-972.

- ↑ McQuillan G, Kruszon-Moran D, Flagg EW, Paulose-Ram R. Prevalence of Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 and Type 2 in Persons Aged 14-49: United States, 2015-2016. NCHS Data Brief. 2018(304):1-8.

- ↑ Jump up to: 7.0 7.1 7.2 Farooq AV, Shukla D. Herpes simplex epithelial and stromal keratitis: an epidemiologic update. Surv Ophthalmol. 2012;57(5):448-462.

- ↑ Predictors of recurrent herpes simplex virus keratitis. Herpetic Eye Disease Study Group. Cornea 20, 123-128 (2001).

- ↑ Young, R.C., Hodge, D.O., Liesegang, T.J. & Baratz, K.H. Incidence, recurrence, and outcomes of herpes simplex virus eye disease in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1976-2007: the effect of oral antiviral prophylaxis. Arch Ophthalmol 128, 1178-1183 (2010).

- ↑ Jump up to: 10.0 10.1 Lobo AM, Agelidis AM, Shukla D. Pathogenesis of herpes simplex keratitis: The host cell response and ocular surface sequelae to infection and inflammation. Ocul Surf. 2019;17(1):40-49.

- ↑ Jump up to: 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 Roozbahani, M. & Hammersmith, K.M. Management of herpes simplex virus epithelial keratitis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 29, 360-364 (2018).

- ↑ Arshad S, Petsoglou C, Lee T, Al-Tamimi A, Carnt NA. 20 years since the Herpetic Eye Disease Study: Lessons, developments and applications to clinical practice. Clin Exp Optom. 2021;104(3):396-405.

- ↑ Jump up to: 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 Roozbahani M, Hammersmith KM. Management of herpes simplex virus epithelial keratitis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2018;29(4):360-364.

- ↑ Majtanova, N., et al. Herpes Simplex Keratitis in Patients with SARS-CoV-2 Infection: A Series of Five Cases. Medicina (Kaunas) 57(2021).

- ↑ Alkwikbi, H., Alenazi, M., Alanazi, W. & Alruwaili, S. Herpetic Keratitis and Corneal Endothelitis Following COVID-19 Vaccination: A Case Series. Cureus 14, e20967 (2022)

- ↑ Jump up to: 16.0 16.1 Subhan S, Jose RJ, Duggirala A, et al. Diagnosis of herpes simplex virus-1 keratitis: comparison of Giemsa stain, immunofluorescence assay and polymerase chain reaction. Curr Eye Res. 2004;29(2-3):209-213.

- ↑ Tabery HM. Epithelial changes in early primary herpes simplex virus keratitis. Photomicrographic observations in a case of human infection. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2000;78(6):706-709.

- ↑ White ML, Chodosh J. Herpes Simplex Virus Keratitis: A Treatment Guideline. AAO Compendium of Evidence-Based Eye Care; 2014. Available at: http:// www.aao.org/clinical-statement/herpes-simplex-virus-keratitis-treatment- guideline. [Accessed 26 October 2015]

- ↑ Ching SST, Feder RS, Hindman HB, et al. Herpes simplex epithelial keratitis. Preferred Practice Pattern clinical questions. Am Acad Ophthalmol 2012; 1 – 8.

- ↑ Wilhelmus KR. Antiviral treatment and other therapeutic interventions for herpes simplex virus epithelial keratitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015; 1:CD002898.

- ↑ Kalogeropoulos D, Geka A, Malamos K, et al. New therapeutic percep- tions in a patient with complicated herpes simplex virus 1 keratitis: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Case Rep 2017; 18: 1382 – 1389.

- ↑ Austin A, Lietman T, Rose-Nussbaumer J. Update on the Management of Infectious Keratitis. Ophthalmology. 2017;124(11):1678-1689.

- ↑ Wilhelmus KR, Beck RW, Moke PS, et al. Acyclovir for the Prevention of Recurrent Herpes Simplex Virus Eye Disease. New England Journal of Medicine 1998; 339:300–306.

- ↑ Reed JW, Joyner SJ, Knauer WJ. Penetrating Keratoplasty for Herpes Zoster Keratopathy. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 1989;107(3):257-261.