Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis (LCH) is a collection of rare disorders of the mononuclear phagocytes and dendritic cells. Other disorders similar to LCH include Histiocytoses Rosai-Dorfman, juvenile xanthogranuloma, and Erdheim-Chester disease but they do not share the exact phenotypic signature of LCH.

Disease Entity

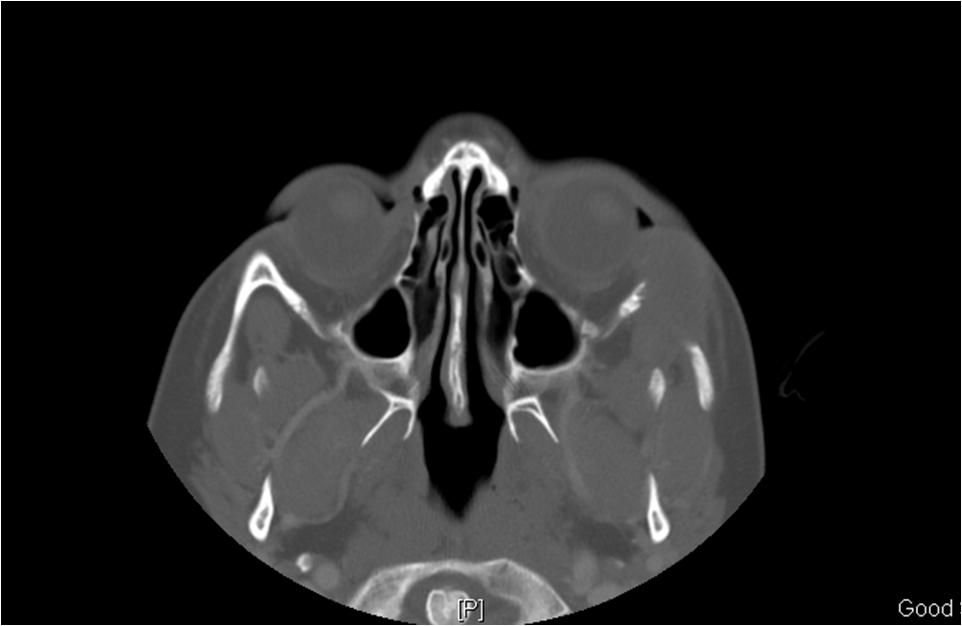

Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis (LCH) involving the orbit.[1]

Disease

Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis (LCH), formerly known as “histiocytosis X,” historically includes three subgroups: eosinophilic granuloma, Hand-Schuller-Christian disease, and Letterer-Siwe disease, representing a spectrum from unifocal to multifocal/multisystem involvement. The lesions of LCH may involve the bones, skin, hypothalamus-pituitary region, as well as other organs.[2]

Pathophysiology

While the characteristic granuloma-like lesions of LCH consists of Langerhans cells, macrophages, eosinophils, T lymphocytes and plasma cells, it is thought that clonal expansion of defective immature Langerhans cells is the key pathogenetic element.[3]

Etiology

Langerhans cell histiocytosis remains an enigmatic disease and the dispute over its neoplastic versus reactive nature is unsettled. The disorder is currently thought to result from transient immune dysfunction (such as a viral infection) which may provoke the cytokine-mediated proliferation of pathologic Langerhans cells within the hematopoietic marrow of the affected bone. This understanding of histiocyte development is based on in vitro studies and suggests an immune/inflammatory insult leads susceptible langerhans cells to undergo a clonal expansion resulting in LCH.[4][5][6]

Incidence

LCH is predominantly a disease of childhood with a peak incidence between 1 and 10 years. Children less than 2 years tend to have more aggressive disease with a worse prognosis. The estimated annual incidence is 2-5 in one million children and represents 1% to 3% of pediatric orbital tumors.[7][8] In a retrospective chart review of 24 consecutive patients with LCH treated at a tertiary referral center, the orbit was involved in 9 (37.5%) of patients. The most common site of involvement was the frontal bone (n = 6) followed by zygomatic (n = 3), sphenoid (n = 3), and maxillary (n = 2).[9]

Diagnosis

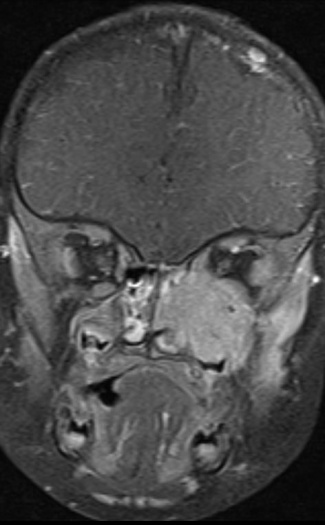

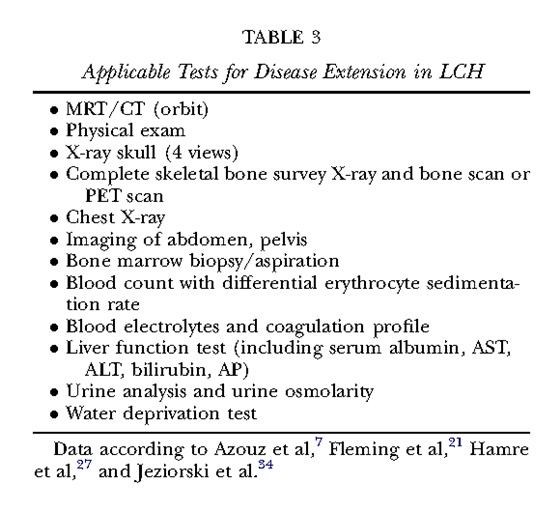

On imaging presentation is variable but it typically presents as a lytic defect most commonly seen in superotemporal orbit or sphenoid wing. The LCH disorders have a predilection for hematopoietically active bone marrow so this is why it is seen in the supero-temporal orbit quite commonly. LCH lesions enhanced only minimally with contrast on CT. On T1-weighted MRI images typically showed soft tissue masses with signal intensity similar to muscle, and enhances well with fat-suppression and gadolinunium. [10] The histological diagnosis of LCH lesions is based on staining for S-100 protein and CD1a antigen or finding Birbeck granules (shaped like tennis racquets) on electron microscopy.[11][12]

Temporal bone involvement has been reported and is extremely rare; this presentation may be confused initially with mastoiditis.

History

Epidermal langerhans cells were first described by the German physician Paul Langerhans in 1868. Because the branched cells demonstrated an affinity for gold chloride (a stain for nervous tissue) the cells were thought to be of neural origin. The hematopoietic origin and antigen presenting function of the dendritic cells would remain unknown for more than a century.[13]

Differential diagnosis

Orbital cellulitis is the most common cause of proptosis in children. Orbital pseudotumor represents the second most common inflammatory disorder of the orbit in childhood and may present with unilateral or bilateral proptosis of explosive onset with restriction of ocular motility. Less common orbital inflammatory process that should be considered include granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA; formerly known as Wegener's), sarcoidosis, and Langerhans cell histiocytosis, with the latter occurring in childhood more frequently. If imaging reveals a bony defect and/or the presentation is of rapid onset, the tumors histopathologically described as the “small round blue-cell tumors of childhood” should be considered and include rhabdomyosarcoma, leukemia, and metastatic neuroblastoma.[14]

As a general clinical pearl, if you do see a lytic bony changes on CT in a child you should strongly consider this disease as a possible diagnosis. However, while imaging findings are fairly uniform in LCH, they are not pathognomonic, and other serious conditions in the same age group can have similar manifestations such Neuroblastoma, Ewing sarcoma, and Wilms tumor (all of which can each metastasize to the pediatric orbit). [15]

Management and Treatment

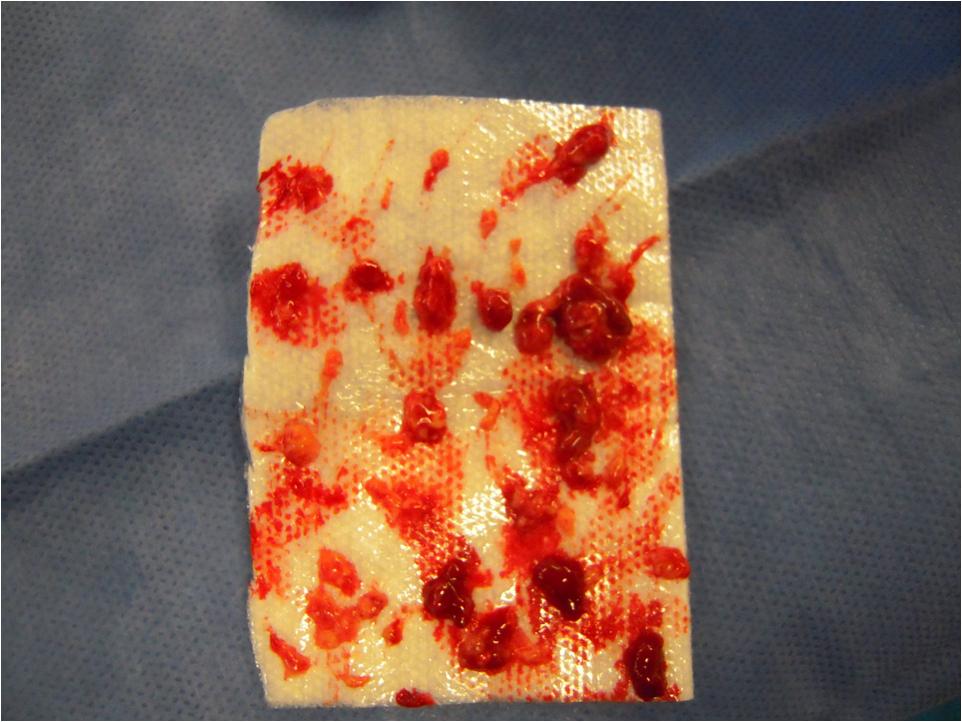

All patients with unifocal orbital disease require a biopsy to establish and confirm the diagnosis and rule out other malignant disease. Patients should be referred to a pediatric oncologist for a comprehensive systemic evaluation and ongoing follow-up in order to monitor for recurrence or progression. Single-system disease confined to a single site (e.g., small orbital lesions withoutintracranial extension) usually only requires local therapy (e.g., curettage, steroid injection or radiation therapy) or observation. On the other hand, multifocal disease usually requires systemic therapy with prednisone with or without chemotherapeutic agents (vinblastine and/or etoposide) depending on the extent of the disease.[16]

Therapy for localized Orbital LCH:

There are many options and the treatment is controversial. Overall, there has not been enough long term data to clearly show any treatment is superior and controversy exists in the literature.[17][18][19]

In one of the larger studies of 23 patients with unifocal orbital disease; over a 4.5 year period

- 13 had Surgery alone

- 6 had Surgery with adjuvant chemotherapy;

- 1 had Surgery with intralesional triamcinolone;

- 1 had chemotherapy alone;

- and 2 were observed after biopsy

There were 3 recurrences, which were seen in the 1 patient who got steroid and 2 patients who go adjuvant chemo. Generally it is felt that the recurrence rate is probably around 15%.[20]

Despite these study results response of LCH to all modalities mentioned has been documented, mainly outside of the orbit and the bulk of experience with intralesional steriod and low-dose radiation is taken from non-orbital bones where efficacy approaches 90% resolution ( resolution 31 of 35 lesions (89%) after a single intralesional injection of methylprednisolone). Also, after resolution of the lytic lesions re-ossification of the affected bones happens quickly and deformity is reported to be minimal. Based on these favorable responses to most therapies. It is suggested by some ((Woo and Harris, 2003)) that therapy of orbital LCH should be limited curettage and intralesional corticosteroids, thereby sparing children with rapidly resolving disease the morbidity of chemotherapy unless recurrent disease is encountered at which point radiation or chemotherapy can be performed. [21][22]

It is suggested by others that it is important to distinguish between lesions in the orbital bones with intracranial soft tissue extension verus simple and easily accessible orbital lesions without a prominent retroorbital or intracranial soft tissue component. Lesions with a prominent retroorbital or intracranial soft tissue component can be regarded as CNS-Risk lesions which mandate systemic therapy under the International Treatment Protocol for systemic/multifocal Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis (LCH-III) . They suggest that chemotherapy with vinblastine and prednisone, as offered in the LCH-III protocol, may be the less invasive strategy in extended infiltrative lesions or in lesions that fail to regress after initial biopsy (Grois and Gadner, 2004).[23][24]

Prognosis

Prognosis in this disease is good as long as multifocal or systemic disease is not present and children are older than age 2. Overall survival of children aged less than 2 years is 50%, while chilren age greater than 2 is 87%. In general, younger children are more likely to have multifocal or systemic involvement. The morbidity of LCH results from the mass effect of proliferating pathologic Langerhans cells within multiple organs, and involved sites can include bone, skin, lymph nodes, spleen, lung, liver, brain, and the gastrointestinal tract. The orbital involvement by LCH most often represents isolated unifocal disease but even if the initial workup is negative they will need to be regularly observed for detection of subsequent multi organ involvement. [25][26]

Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis represents a spectrum from the benign unifocal bone lesion to aggressive multisystem disease. In a large cohort study of 314 Mayo Clinic patients with histologically proven LCH, 97% (114 of 314) of patients with isolated bone LCH lesions achieved disease free survival after treatment. The proportion of patients achieving disease free survival was significantly less in patients with multisystem disease versus single system disease (74% vs. 91%; P <0.003; 95% CI, 0.26 and 0.08).[27] While isolated LCH of the orbit is thought to be a relatively benign condition responsive to limited local treatment, it should be noted that in a recent retrospective study by Vosoghi, et al. 7 of 9 patients with unifocal bone disease progressed to multifocal bone disease during follow-up, including 2 patients with unifocal orbital disease. Even though these results may be inflated due to a strong referral bias, the study highlights the possible progression of unifocal bone disease and the importance of a comprehensive workup and follow-up.[28]

References

- ↑ Hester CC, Silkiss RZ. The Cellulitis That Wouldn’t Go Away. Morning Rounds. EyeNet. Morning Rounds. EyeNet. October 2010.

- ↑ Savasan, S. Int J Dermatol 2006;45:182–188.

- ↑ Savasan, S. Int J Dermatol 2006;45:182–188.

- ↑ Savasan S. An enigmatic disease: childhood Langerhans cell histiocytosis in 2005. Int J Dermatol 2006;45:182-8.

- ↑ Herwig, et al. Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis of the Orbit: Five Clinicopathologic Cases and Review of the Literature. Surv Ophthalmol 58 (4) July--August 2013

- ↑ Woo K and Harris G. Eosinophilic Granuloma of the Orbit: Understanding the Paradox of Aggressive Destruction Responsive to Minimal Intervention. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg, Vol. 19, No. 6, 2003

- ↑ Vosoghi, H. et al. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2009;25:430–433.

- ↑ Savasan, S. Int J Dermatol 2006;45:182–188.

- ↑ Castillo, B. V. and L. Kaufman. Pediatr Clin North Am 2003;50:149–172.

- ↑ Koch, Bernadette. Langerhans Histiocytosis of Temporal Bone: Role of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Top Magn Reson Imaging. 2000 Feb;11(1):66-74.

- ↑ Savasan, S. Int J Dermatol 2006;45:182–188.

- ↑ Harris, G. J. Am J Ophthalmol 2006;141:374–378.

- ↑ Namazi, M. R. Arch Dermatol 2008;144:1109.

- ↑ Hurwitz CA, et al. N Engl J Med 2002;346:513-20.

- ↑ Chung, et al. Pediatric Orbit Tumors and Tumorlike Lesions: Osseous Lesions of the Orbit. Radiographics. 1196 July-August 2008. Volume 28 • Number 4

- ↑ Vosoghi, H. et al. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2009;25:430–433.

- ↑ Maccheron, et al. Ocular Adnexal Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis Clinical Features and Management. Orbit, 25:169–177, 2006

- ↑ Allen CE, McClain KL. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: a review of past, current and future therapies. Drugs Today (Barc). 2007 Sep;43(9):627-43.

- ↑ Woo K and Harris G. Eosinophilic Granuloma of the Orbit: Understanding the Paradox of Aggressive Destruction Responsive to Minimal Intervention. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg, Vol. 19, No. 6, 2003

- ↑ Herwig, et al. Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis of the Orbit: Five Clinicopathologic Cases and Review of the Literature. Surv Ophthalmol 58 (4) July--August 2013

- ↑ Woo K and Harris G. Eosinophilic Granuloma of the Orbit: Understanding the Paradox of Aggressive Destruction Responsive to Minimal Intervention. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg, Vol. 19, No. 6, 2003

- ↑ Maccheron, et al. Ocular Adnexal Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis Clinical Features and Management. Orbit, 25:169–177, 2006

- ↑ Allen CE, McClain KL. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: a review of past, current and future therapies. Drugs Today (Barc). 2007 Sep;43(9):627-43

- ↑ Maccheron, et al. Ocular Adnexal Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis Clinical Features and Management. Orbit, 25:169–177, 2006

- ↑ Woo K and Harris G. Eosinophilic Granuloma of the Orbit: Understanding the Paradox of Aggressive Destruction Responsive to Minimal Intervention. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg, Vol. 19, No. 6, 2003

- ↑ Maccheron, et al. Ocular Adnexal Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis Clinical Features and Management. Orbit, 25:169–177, 2006

- ↑ Howarth, D. M. et al. Cancer 1999;85: 2278–2290.

- ↑ Vosoghi, H. et al. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2009;25:430–433.