Blepharokeratoconjunctivitis (BKC) of Childhood

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Blepharokeratoconjunctivitis (BKC) of childhood is a chronic inflammatory disease of the palpebral margin associated with secondary conjunctival and corneal involvement. The disorder has a wide range of clinical manifestations, including chronically inflamed eyelids, meibomian gland dysfunction, lid margin telangiectasias, collarettes at the bases of the eyelashes, recurrent chalazia, conjunctivitis, keratopathy, and even amblyopia and vision loss. The most common corneal findings in BKC are superficial punctate keratitis, corneal infiltrates, marginal ulceration, and corneal vascularization.[1] Several other names have been used to describe this disorder previously, such as staphylococcal blepharokeratitis, phlyctenular keratitis, and childhood rosacea. Meibomitis-related keratoconjunctivitis or meibomitis-related phlyctenular keratoconjunctivitis have also been proposed terms given the universal presence of meibomitis in BKC.[2] BKC is well-defined in adults and usually described in association with acne rosacea;[3] however, the clinical course of BKC and its effects on vision may differ in children. Most notably, children tend to have more severe disease with more frequent corneal involvement. BKC usually presents between 6 months of age and adolescence, most commonly in children ages 4-5 years. [4][5]

Epidemiology

BKC in children is a relatively common condition but is often under-recognized. A retrospective case series in the United States reported that 15% of patients referred to a pediatric cornea clinic carried a diagnosis of BKC.[6] A larger case series in India reported a 12% incidence of BKC in a single ophthalmology clinic over a three-year period.[7]

Risk Factors

BKC is more common in South Asian and Middle Eastern children.[8] It may have a greater predilection for females, although this is not consistent across all studies.[9][10][11] Risk factors for BKC with corneal involvement, which indicates more severe disease, may include female gender, asymmetric disease, diagnosis at older age, and the presence of photophobia.[12]

Pathophysiology

It is unclear whether the various clinical manifestations of BKC represent differences in pathogenesis or different levels of disease activity. Bacterial colonization of the conjunctiva and eyelids with Staphylococcus aureus, Propionibacterium acnes, or Corynebacteria may stimulate the release of inflammatory cytokines from the ocular surface and destabilize the tear film via release of free fatty acids by bacterial phospholipases.[13] Inflammation may also result from a delayed type IV hypersensitivity reaction to bacterial cell wall antigens (e.g., protein A, teichoic acid) or from the direct toxic effects of staphylococcal exotoxins (alpha, beta, and gamma hemolysin) on the ocular surface. Some studies suggest that Demodex, a parasitic mite that lives in hair follicles and sebaceous glands, may play a role in the ocular surface changes seen in BKC.[14] Affected patients likely possess an immune-genetic susceptibility to disease development, as well. The meibomian gland dysfunction in BKC is the result of ductal hyperkeratinization, as well as qualitative and quantitative changes in meibomian glandular secretions, although the trigger(s) for these events remain unclear.[15] One theory as to why children are more susceptible to corneal involvement than adults with BKC is due to an exaggerated and immature immune adaptive response against bacterial antigens.[16]

Primary Prevention

Early diagnosis is critical to prevent severe disease. Children who are diagnosed at older ages are at higher risk for corneal involvement.[17]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of BKC is largely clinical. There are no specific diagnostic criteria or universal grading systems for the severity of clinical signs observed in BKC.

Symptoms

Children often present with ocular redness, tearing, burning, epiphora, foreign body sensation, intermittently blurred vision, photophobia, and recurrent chalazia or styes. These symptoms are often chronic, but acute exacerbations of symptoms may occur. Reduced vision may also occur in cases with corneal involvement.[18]

Signs

The following signs are observed in BKC.[19][20][21]

- Typically bilateral ocular involvement, although may be asymmetric

- Chronic anterior and/or posterior blepharitis:

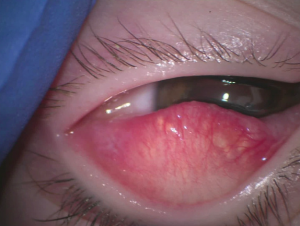

- Anterior blepharitis is inflammation of the anterior lid margin, hair follicles, and oil glands. Signs include scaling, crusting, and erythema of the eyelid margin with collarette formation at the base of the cilia.

- Posterior blepharitis is associated with meibomian gland dysfunction, which may result in pouting or plugging of meibomian orifices, expression of meibomian secretions, telangiectasia of the posterior lid, and eventual thickening and scalloping of the eyelid margin.

- Recurrent chalazia

- Conjunctival hyperemia, chemosis, phlyctenules

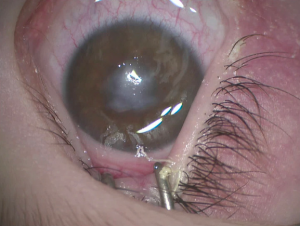

- Corneal inflammation. The frequency of corneal involvement varies significantly across studies, it has been reported in 5% to 100% of cases. Corneal findings include punctate epithelial erosions, marginal infiltrates, phlyctenules, neovascularization or pannus formation. Corneal scarring is typically inferior and peripheral. In severe cases, scarring may be widespread and central. Corneal perforation is rare but may occur.

- Cutaneous manifestations of rosacea—facial erythema, telangiectasias, flushing, and papules and pustules on the cheeks, chin, forehead, and nasolabial folds—are present in 20-50% of children with BKC.

- Reduced visual acuity due to corneal opacification or induced refractive changes

History and Physical Examination

When taking a history in a patient with BKC, one should elicit a description of the patient’s ocular symptoms including duration and recurrences, as well as bilateral or unilateral eye involvement. The history should also include exacerbating conditions (e.g. allergens, contacts lenses), current and previous systemic and topical medications, medical history (e.g. atopy, acne, recurrent chalazia, history of conjunctivitis and/or keratitis), and family history (e.g. rosacea, atopy).

The physical exam should include examination of the patient’s skin to look for signs of rosacea. Visual acuity should be assessed and a cycloplegic refraction performed to monitor for secondary refractive changes and amblyopia. If possible, a slit lamp examination should be performed to examine the anterior lid margin, posterior lid margin, meibomian gland secretions, eyelashes, bulbar and tarsal conjunctiva (including eversion of the upper eyelid), tear film discharge or debris. Finally, fluorescein staining should be performed in order to measure the tear film breakup time and assess the cornea for punctate epithelial erosions or frank ulceration.[22][23]

Tests

Lid and conjunctival swabs for microscopy and direct inoculation onto agar plates for culture and sensitivities may be performed in cases of recurrent and refractory disease.[24] Some studies have also supported the use of infrared meibography devices for quick image and video capture of the meibomian gland structures in children, including infants.[25] In older children, the Schirmer’s test may also be used to evaluate for secondary dry eye.

Differential Diagnosis

The main differential diagnosis to consider is chronic allergic eye disease, including vernal keratoconjunctivitis (VKC) and atopic keratoconjunctivitis (AKC). These entities may appear very similar to BKC, resulting in frequent misdiagnosis.[26] In VKC and AKC, patients frequently report histories of atopic diseases (e.g., dermatitis, asthma) and present with significant papillary reactions on exam. Classically, VKC occurs in early childhood, is self-limited, and involves the upper tarsal conjunctiva, while AKC develops in adolescence or young adulthood, is more chronic in nature, and involves the lower tarsal conjunctiva. VKC is characterized by limbal inflammation, resulting in characteristic Horner-Trantas dots on the peripheral cornea. Given its chronicity, AKC tends to be more severe than VKC, often resulting in the development of a shield ulcer and/or corneal scarring. Herpes simplex keratitis and viral conjunctivitis are also on the differential. Features favoring a diagnosis of herpes simplex include unilateral keratoconjunctivitis, corneal desensitization, and dendritic ulcers. While viral conjunctivitis may appear similar to BKC, BKC is associated with disease recurrence and more significant lid involvement. Other differential diagnoses to consider include seasonal allergic conjunctivitis, giant papillary conjunctivitis, and isolated chalazion. [27]

Management

Treatment

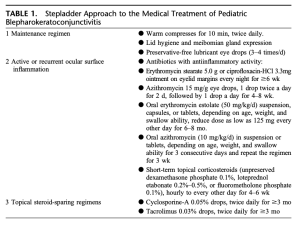

Therapy targets both the inflammatory and infectious components of the disorder. Components of effective therapy are described in the list below.[28][29][30][31][32]

- Lid therapy is indicated regardless of disease severity. Lid therapy should be continued indefinitely due to the chronic nature of BKC. The goal of lid therapy is to soften and clean lid debris and promote meibum outflow.

- Warm compresses

- Lid massage and lid scrub with dilute baby shampoo

- Daily oral flaxseed oil (1 tsp/day for toddlers, 1 tbsp/day for older children)

- In addition to a home lid therapy regimen, patients may require Meibomian gland expression in the clinic or operating room

- Topical/systemic antibiotics

- Topical antibiotics with broad Gram-positive coverage (e.g., erythromycin, azithromycin) are used to reduce bacterial colonization of the lid margin.

- Oral antibiotics are indicated when inflammation is more significant in order to control the lid disease. A macrolide antibiotic may be used in children of any age and is the best choice in a younger child (<8 years old). Tetracycline antibiotics should be avoided in younger children, though they can be used safely in older children (at least 8 years of age). Treatment with oral agents typically lasts for 3-6 months and should be tapered based on the patient’s clinical course.

- Topical glucocorticoids are used to control secondary corneal inflammation and limit scarring. Steroid therapy should be limited to reduce the risk of side effects such as glaucoma and skin thinning/depigmentation.

- For short-term acute exacerbations (<2 months), prednisolone 1% or dexamethasone 0.1% may be used. If longer-term therapy is needed, consider lower-potency steroids, such as loteprednol and fluorometholone.

- Topical cyclosporine A may be used as a steroid-sparing agent.

- Systemic immunosuppression

- While rarely necessary, azathioprine and mycophenolate mofetil have been used in severe cases.

- Adjuvant therapy

- Topical lubricants (preservative-free) are used to treat evaporative dry eye due to meibomian gland dysfunction. Punctal plugs may be considered in children who cannot tolerate drops. Use of smartphones should also be limited in children with dry eye to prevent reduced blinking.

- Patients require monitoring for amblyopia, including cycloplegic refraction and treatment with glasses and patching accordingly.

Follow Up

Long-term follow up is required due to the chronic course of BKC, which may be associated with severe exacerbations.

Prognosis

Delayed diagnosis is associated with decreased vision.[34] Some children may achieve improvement or resolution of symptoms within 1-3 months of starting treatment. The proportion of children who progress to an adult form of BKC or rosacea is unknown. BKC can resolve permanently before adulthood in some instances.[35]

References

- ↑ Viswalingam M, Rauz S, Morlet N, Dart JK. Blepharokeratoconjunctivitis in children: diagnosis and treatment. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89(4):400-403.

- ↑ Suzuki T, Mitsuishi Y, Sano Y, Yokoi N, Kinoshita S. Phlyctenular keratitis associated with meibomitis in young patients. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140(1):77-82.

- ↑ McCulley JP, Dougherty JM, Deneau DG. Classification of chronic blepharitis. Ophthalmology. 1982;89(10):1173-1180.

- ↑ Hammersmith KM. Blepharokeratoconjunctivitis in children. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2015;26(4):301-305.

- ↑ Rodríguez-García A, González-Godínez S, López-Rubio S. Blepharokeratoconjunctivitis in childhood: corneal involvement and visual outcome. Eye (Lond). 2016;30(3):438-446.

- ↑ Hammersmith KM, Cohen EJ, Blake TD, Laibson PR, Rapuano CJ. Blepharokeratoconjunctivitis in children. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123(12):1667-1670.

- ↑ Gupta N, Dhawan A, Beri S, D'Souza P. Clinical spectrum of pediatric blepharokeratoconjunctivitis. J aapos. 2010;14(6):527-529.

- ↑ Viswalingam M, Rauz S, Morlet N, Dart JK. Blepharokeratoconjunctivitis in children: diagnosis and treatment. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89(4):400-403.

- ↑ Hammersmith KM. Blepharokeratoconjunctivitis in children. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2015;26(4):301-305.

- ↑ Hammersmith KM, Cohen EJ, Blake TD, Laibson PR, Rapuano CJ. Blepharokeratoconjunctivitis in children. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123(12):1667-1670.

- ↑ Wu M, Wang X, Han J, Shao T, Wang Y. Evaluation of the ocular surface characteristics and Demodex infestation in paediatric and adult blepharokeratoconjunctivitis. BMC Ophthalmol. 2019;19(1):67.

- ↑ Rodríguez-García A, González-Godínez S, López-Rubio S. Blepharokeratoconjunctivitis in childhood: corneal involvement and visual outcome. Eye (Lond). 2016;30(3):438-446.

- ↑ Gupta N, Dhawan A, Beri S, D'Souza P. Clinical spectrum of pediatric blepharokeratoconjunctivitis. J AAPOS. 2010;14(6):527-529.

- ↑ Wu M, Wang X, Han J, Shao T, Wang Y. Evaluation of the ocular surface characteristics and Demodex infestation in paediatric and adult blepharokeratoconjunctivitis. BMC Ophthalmol. 2019;19(1):67.

- ↑ Geerling G, Tauber J, Baudouin C, et al. The international workshop on meibomian gland dysfunction: report of the subcommittee on management and treatment of meibomian gland dysfunction. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(4):2050-2064.

- ↑ Jones SM, Weinstein JM, Cumberland P, Klein N, Nischal KK. Visual outcome and corneal changes in children with chronic blepharokeratoconjunctivitis. Ophthalmology. 2007;114(12):2271-2280.

- ↑ Rodríguez-García A, González-Godínez S, López-Rubio S. Blepharokeratoconjunctivitis in childhood: corneal involvement and visual outcome. Eye (Lond). 2016;30(3):438-446.

- ↑ Hammersmith KM. Blepharokeratoconjunctivitis in children. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2015;26(4):301-305.

- ↑ Zaidman GW. The pediatric corneal infiltrate. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2011;22(4):261-266.

- ↑ Hammersmith KM. Blepharokeratoconjunctivitis in children. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2015;26(4):301-305.

- ↑ Wong IB, Nischal KK. Managing a child with an external ocular disease. J aapos. 2010;14(1):68-77.

- ↑ Hammersmith KM. Blepharokeratoconjunctivitis in children. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2015;26(4):301-305.

- ↑ Wu M, Wang X, Han J, Shao T, Wang Y. Evaluation of the ocular surface characteristics and Demodex infestation in paediatric and adult blepharokeratoconjunctivitis. BMC Ophthalmol. 2019;19(1):67.

- ↑ Hamada S, Khan I, Denniston AK, Rauz S. Childhood blepharokeratoconjunctivitis: characterising a severe phenotype in white adolescents. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012;96(7):949-955.

- ↑ Shirakawa R, Arita R, Amano S. Meibomian gland morphology in Japanese infants, children, and adults observed using a mobile pen-shaped infrared meibography device. Am J Ophthalmol. 2013;155(6):1099-1103.e1091.

- ↑ Daniel MC, O’Gallagher M, Hingorani M, Dahlmann-Noor A, Tuft S. Challenges in the management of pediatric blepharokeratoconjunctivis / ocular rosacea. Expert Review of Ophthalmology. 2016;11(4):299-309.

- ↑ Hammersmith KM. Blepharokeratoconjunctivitis in children. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2015;26(4):301-305.

- ↑ Hammersmith KM. Blepharokeratoconjunctivitis in children. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2015;26(4):301-305.

- ↑ Jones SM, Weinstein JM, Cumberland P, Klein N, Nischal KK. Visual outcome and corneal changes in children with chronic blepharokeratoconjunctivitis. Ophthalmology. 2007;114(12):2271-2280.

- ↑ Hamada S, Khan I, Denniston AK, Rauz S. Childhood blepharokeratoconjunctivitis: characterising a severe phenotype in white adolescents. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012;96(7):949-955.

- ↑ Daniel MC, O’Gallagher M, Hingorani M, Dahlmann-Noor A, Tuft S. Challenges in the management of pediatric blepharokeratoconjunctivis / ocular rosacea. Expert Review of Ophthalmology. 2016;11(4):299-309.

- ↑ Moon JH, Lee MY, Moon NJ. Association between video display terminal use and dry eye disease in school children. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2014;51(2):87-92.

- ↑ Ortiz-Morales G, Morales-Mancillas NR, Paez-Garza JH, Rodriguez-Garcia A. Letter Regarding: Clinical Characteristics and Therapeutic Outcomes of Pediatric Blepharokeratoconjunctivitis. Cornea. 2023 Jun 1;42(6):e10-e11. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000003259. Epub 2023 Feb 15. PMID: 36796021.

- ↑ Hammersmith KM. Blepharokeratoconjunctivitis in children. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2015;26(4):301-305.

- ↑ Daniel MC, O’Gallagher M, Hingorani M, Dahlmann-Noor A, Tuft S. Challenges in the management of pediatric blepharokeratoconjunctivis / ocular rosacea. Expert Review of Ophthalmology. 2016;11(4):299-309.