Phlyctenular Keratoconjunctivitis

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease

Phlyctenular keratoconjunctivitis is a nodular inflammation of the cornea or conjunctiva that results from a hypersensitivity reaction to a foreign antigen. Prior to the 1950s, phlyctenular keratoconjunctivitis often presented as a consequence of a hypersensitivity reaction to tuberculin protein due to high prevalence of tuberculosis. It was typically seen in poor, malnourished children with a positive tuberculin skin test. [2][3][4] Following improvements in public health efforts and decreasing rates of tuberculosis, there was a decline in phlyctenular keratoconjunctivitis and subsequent patients were found to have negative tuberculin tests.[4][5][6] Currently in the United States, microbial proteins of Staphylococcus aureus are the most common causative antigens in phlyctenular keratoconjunctivitis.[4][7] Risk factors for S. aureus exposure include chronic blepharitis and suppurative keratitis.[7][8] Phlyctenular keratoconjunctivitis is a common cause of pediatric referrals as it occurs primarily in children from 6 months to 16 years old. There is a higher prevalence in females and higher incidence during spring.[3][7][9]

General Pathophysiology

Phlyctenular keratoconjunctivitis is postulated to occur secondary to an allergic, hypersensitivity reaction at the cornea or conjunctiva, following re-exposure to an infectious antigen that the host has been previously sensitized to.[2][7][8] Antigens of Staphylococcus aureus and Mycobacterium tuberculosis are most commonly associated; however, Herpes simplex, Chlamydia, Streptococcus viridians, Dolosigranulum pigram and intestinal parasites including Hymenolepis nana have also been reported as causative agents.[3][5][10][11][12][13]

Histologically, scrapings from affected eyes with phlyctenular keratoconjunctivitis infiltrates show predominantly helper T cells, as well as suppressor/cytotoxic T-lymphocytes, monocytes and Langerhans cells.[9][14] The majority of cell scrapings were HLA-DR positive.[9][14] The presence of antigen presenting cells (Langerhans cells), monocytes and T cells support the rationale that phlyctenular keratoconjunctivitis is likely due to a delayed cell-mediated reaction. Phlyctenular keratoconjunctivitis may have an association with ocular rosacea, a skin condition that may have a similar underlying type IV hypersensitivity origin.[3][14][15] Previous reports of phlyctenular keratoconjunctivitis with associated asthma and allergies also support the notion of an altered immune mechanism contributing to the pathogenesis.[11]

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

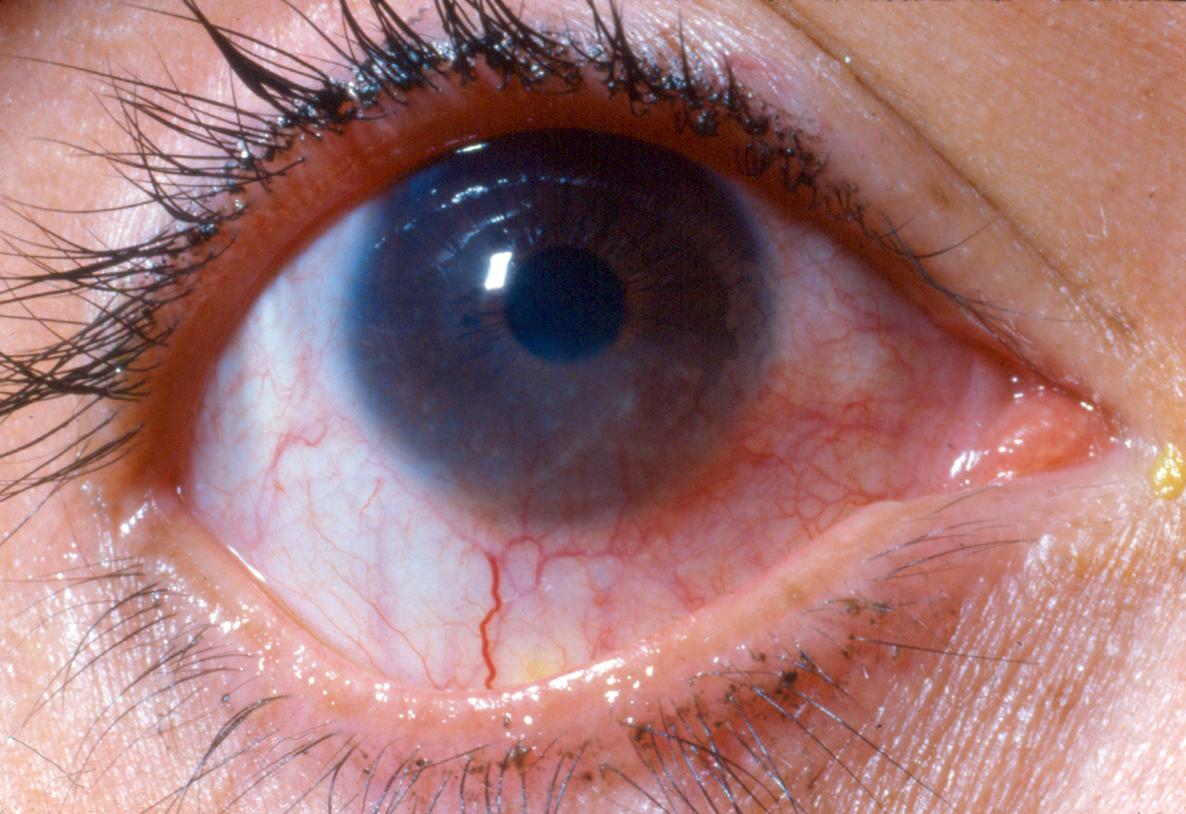

The clinical presentation of phlcytenulosis is dependent on the location of the lesion as well as the underlying etiology. Conjunctival lesions may cause only mild to moderate irritation of the eye, while corneal lesions typically may have more severe pain and photophobia. More severe light sensitivity may also be associated with tuberculosis related phlyctenules compared to S. aureus related phlyctenules.[8] Phlyctenules can occur anywhere on the conjunctiva but are more common in the interpalpebral fissure and are frequently noted along the limbal region. They commonly present with a gelatinous, nodular lesion with marked injection of the surrounding conjunctival vessels. The lesions may show some degree of ulceration and staining with fluorescein as they progress. In some cases, multiple 1-2mm nodules may be present along the limbal surface.

Corneal phlyctenules similarly begin along the limbal region and frequently degenerate to corneal ulceration and neovascularization. In some instances, the phlyctenule will progress across the corneal surface due to repeated episodes of inflammation along the central edge of the lesion. These “marching phlyctenules” demonstrate an elevated leading edge trailed by a leash of vessels.

The diagnosis of phlyctenular keratoconjunctivitis is made based on history and clinical exam findings. The underlying infectious etiology requires further investigation when the possibility of tuberculosis or chlamydia is suspected. Chest radiographs, purified protein derivative skin testing or QuantiFERON-gold testing should be ordered for patients with a history of travel to tuberculosis endemic regions or symptoms consistent with tuberculosis infection. For patients suspected of having chlamydia, immunofluorescent antibody testing and PCR of conjunctival swabs provide quick and accurate screening. If positive, appropriate systemic treatment of these infections is required as well as screening and possible treatment of close contacts.

Differential Diagnosis

- Acne Rosacea Keratitis

- Rosacea Keratoconjunctivitis

- Staphylococcal marginal keratitis

- Nodular Episcleritis

- Salzmann’s Nodules

- Trachoma

- Inflamed Pigueculum/Pterygium

- Vernal Keratoconjunctivitis

- Infectious Corneal Ulcer with Vascularization

- Catarrhal Ulcer

- Peripheral Ulcerative Keratitis

- Herpes Simplex Keratitis or Keratoconjunctivitis

Complications

Phlyctenular nodules can lead to ulceration, scarring and mild to moderate vision loss.[3][15] Although rare, corneal perforation is possible as well.[3][16]

General treatment

The first line of treatment for phlyctenular keratoconjunctivitis is to decrease the inflammatory response. Phlyctenulosis is generally responsive to topical steroids. However, risk of rise of intraocular pressure has to be kept in mind. In cases with multiple recurrences, or those which become steroid dependent, topical cyclosporine A is an effective treatment option.[17] The use of cyclosporine A may reduce the sequelae of long term steroid use such as cataracts, ocular hypertension and decreased wound healing. In cases with corneal ulceration, pretreatment or concurrent use of an antibiotic is recommended. Corneal cultures may also be considered prior to starting treatment.

In addition to treating the inflammatory response, it is important to decrease the source of antigens inciting the inflammation. This usually requires treating the associated blepharitis or underlying infectious process. In cases of blepharitis, lid hygiene with warm compresses and lid scrubs should be started. One study found that 1.5 % topical azithromycin was effective in treating phlyctenular keratoconjunctivitis with underlying ocular rosacea.[18] Adjunctive treatment with oral doxycycline may also be of benefit. In children under the age of 8, erythromycin is preferred to prevent dental discoloration from tetracycline use.[3]

In patients with communicable diseases such as tuberculosis and chlamydia, the underlying infections should be properly addressed and treated appropriately. Chlamydia induced phlyctenular keratoconjunctivitis should be treated with azithromycin or doxycycline. Patients with positive tuberculin tests should be referred to receive proper systemic treatment of tuberculosis. Close contacts should also be evaluated and treated fittingly.

In rare instances of corneal perforation, surgical treatment may be required. Options for treating peripheral perforations include corneal gluing, amniotic membrane grafting, or corneal patch grafts.

References

- ↑ American Academy of Ophthalmology. Staph phlyctenular keratoconjunctivitis. https://www.aao.org/image/staph-phlyctenular-keratoconjunctivitis-2 Accessed October 10, 2017.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Thygeson P. The etiology and treatment of phlyctenular keratoconjunctivitis. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 1951;34(9):1217-1236.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 Culbertson WW, Huang AJ, Mandelbaum SH, Pflugfelder SC, Boozalis GT, Miller D. Effective treatment of phlyctenular keratoconjunctivitis with oral tetracycline. Ophthalmology. 1993;100(9):1358-1366.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Rohatgi J, Dhaliwal U. Phlyctenular eye disease: a reappraisal. Japanese Journal of Ophthalmology. 2000;44(22):146-150.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Thygeson P. Observations on nontuberculous phlyctenular keratoconjunctivitis. Transactions: American Academy of Ophthalmology and Otolaryngology. 1954;58(1):128–132.

- ↑ Thygeson P. Nontuberculous phlyctenular keratoconjunctivitis. In: Golden B, eds. Ocular Inflammatory Disease. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas Publisher LTD; 1974.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Beauchamp GR, Gillete TE, Friendly DS. Phlyctenular keratoconjunctivitis. Journal of Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. 1981;18(3):22-28.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Ostler HB, Lanier JD. Phlyctenular keratoconjunctivitis with special reference to the staphylococcal type. Transactions of the Pacific Coast Oto-Ophthalmologic Society Annual Meeting. 1974;55:237-252.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Abu El Asrar AM, Geboes K, Maudgal PC, Emarah MH, Missotten L, Desmet V. Immunocytological study of phlyctenular eye disease. International Ophthalmology. 1987;10(1):33-39.

- ↑ Juberias RJ, Calonge M, Montero J, Herreras JM, Saornil AM. Phlyctenular keratoconjunctivitis a potentially blinding disorder. Ocular Immunology and Inflammation. 1996;4(2):119-123.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Venkateswaran N, Kalsow CM, Hindman HB. Phlyctenular keratoconjunctivitis associated with Dolosigranulum pigrum. Ocular Immunology and Inflammation. 2014;22(3):242-245.

- ↑ Al-Amry MA, Al-Amri A, Khan AO. Resolution of childhood recurrent corneal phlyctenulosis following eradication of an intestinal parasite. Journal of American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. 2008;12(1):89-90.

- ↑ Holland EJ, Mahanti RL, Belongia EA, Mizener MW, Goodman JL, Andres CW, Osterholm MT. Ocular involvement in an outbreak of herpes gladiatorum. Am J Ophthalmol. 1992 Dec 15;114(6):680-4.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Neiberg MN, Sowka J. Phlyctenular keratoconjunctivitis in a patient with Staphylococcal blepharitis and ocular rosacea. Optometry. 2008;79(3):133-137.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Zaidman GW, Brown SI. Orally administered tetracycline for phlyctenular keratoconjunctivitis. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 1981;92(2):187-182.

- ↑ Ostler HB. Corneal Perforation in nontuberculosis (staphylococcal) phlyctenular keratoconjunctivitis. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 1975;79(3):446-448.

- ↑ Doan S, Gabison E, Gatinel D, Duong MH, Abitbol O, Hoang-Xuan T. Topical cyclosporine A in severe steroid-dependent childhood phlyctenular keratoconjunctivitis. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 2006;141(1):62-66.

- ↑ Doan S, Gabison E, Chiambaretta F, Touati M, Cochereau I. Efficacy of azithromycin 1.5% eye drops in childhood ocular rosacea with phlyctenular blepharokeratoconjunctivitis. Journal of Ophthalmic Inflammation and Infection. 2013;3(1):38.