Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma of the Lacrimal Gland

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Lacrimal gland tumors comprise about 10% of all space-occupying orbital tumors. About 20% of solid lacrimal gland tumors are of epithelial origin, with about 45% being malignant. Of the malignant epithelial lacrimal gland tumors, about 60% are adenoid cystic carcinomas, and these most often involve the orbital lobe of the lacrimal gland.

Diagnosis

Clinical Diagnosis

Adenoid cystic carcinoma generally presents in young or middle-aged adults with a mean age of 40 years, but can occur in the first decade of life. There is a slight predilection for women. Diagnosis of adenoid cystic carcinoma generally occurs within 6 months of presenting signs and symptoms.

Given the superotemporal location of the lacrimal gland in the orbit, often the initial presenting sign is proptosis with inferior and nasal deviation of the globe (Fig. 1). Pain from bone and nerve invasion by this unencapsulated tumor is a distinguishing feature from benign lesions, which tend to be slowly progressive without pain. Nerve invasion may also present with frontotemporal hypoesthesia. Patients may also present with “S-shaped” blepharoptosis, diplopia, and ocular motility deficits.

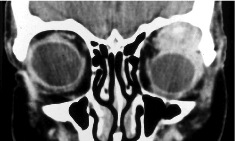

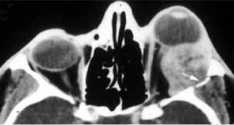

Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may demonstrate an ovoid soft tissue mass in the superotemporal orbit with irregular margins and possible bony erosion even while the tumor is small. Focal calcifications may also be present (Fig. 2A, 2B).

Fig. 1: Proptosis and globe dystopia from left lacrimal gland adenoid cystic carcinoma.

Fig. 2: (A) Coronal CT of an adenoid cystic carcinoma with irregular mass arising from the left anterior superotemporal orbit with possible focal calcification. (B) Axial CT of an adenoid cystic carcinoma invading the left lateral orbital wall (arrow).

Histologic diagnosis

If there is any suggestion from clinical work-up that a lacrimal gland mass is malignant, excisional biopsy at minimum is strongly recommended to prevent further seeding of tumor cells in the orbit. Fine needle aspiration biopsy has been proposed in the literature and may be more appropriate for unresectable tumors, but should be limited to institutions with experienced cytopathologists.

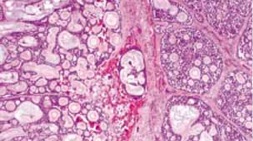

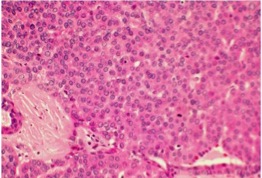

On histology, the tumor is defined by bland appearing, but malignant epithelial cells clearly delineated from adjacent connective tissue. The tumor can present in several subtypes including cribiform (Swiss cheese), sclerosing, basaloid, comedocarcinoma, and tubular (ductal).

The cribiform variant is the most common and consists of lobules with circular pools of mucin (Fig. 3). The sclerosing variant consists of elongated cords of epithelial cells with a dense hyalinized stroma. The basaloid variant is poorly differentiated with large basophilic nuclei and scant cytoplasm in solid epithelial lobules (Fig. 4). This variant has been thought to have a poorer prognosis than the other variants. The comedocarcinoma variant is composed of epithelial lobules with large foci of central necrosis. The tubular variant is made up of elongated epithelial tubules lined by two to three layers of cells.

Fig. 3: Cribriform variant

Fig. 4: Basaloid variant

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnosis includes lymphoma, and other inflammatory conditions including chronic dacryoadenitis, reactive lymphoid hyperplasia, sarcoidosis, Sjögren’s syndrome (Mikulicz disease), lipogranuloma, and dacryops. Pleomorphic adenoma is also an important differential and is the most common lacrimal gland tumor. Pleomorphic adenoma is a benign lacrimal gland tumor, typically painless, but has the potential for malignant transformation. Pleomorphic adenoma (benign mixed tumor) can also demonstrate bony orbital expansion on imaging as well. Also on the differential are other malignant epithelial tumors of the lacrimal gland. Of the malignant epithelial lacrimal tumors 20% are pleomorphic adenocarcinoma, 10% are primary adenocarcinoma, and 5% are mucoepidermoid carcinoma.

Management

Treatment

Treatment continues to be controversial. Many authorities today will often initiate surgery (orbital exenteration vs globe-sparing resection) with or without bone removal and adjuvant radiotherapy (external beam or proton beam therapy). The decision for exenteration may depend on involvement of the orbital apex and extension beyond the orbit. Removal of bone is usually guided by radiologic evidence of bony involvement or intraoperative abnormal bony structures. Radiotherapy is often initiated in cases of perineural invasion. Radiation therapy may also prolong long-term survival. Other less studied modalities of treatment include intraaterial chemotherapy and brachytherapy. Over the past decade, there has been a trend toward an emphasis on adjuvant treatments (rather than surgery alone) such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Most centers currently rely on a combination of all available modalities to reduce local surgical morbidity (when appropriate), combined with adjuvant therapies in an attempt to improve survival rates.

There have been numerous studies looking at outcomes with different modalities of treatment.

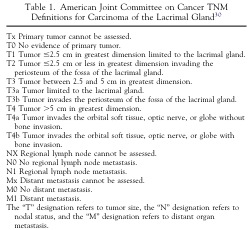

In one study by Ahmad and Esmaeli, a retrospective review of 53 cases of adenoid cystic carcinoma were classified according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer Classification to evaluate predictive outcomes of treatment and local recurrence.[1] The study concluded that prognosis was worse for patients with >T3 tumors (Fig. 5) with higher incidence of recurrence and metastasis despite aggressive treatment. Poor outcome was also noted in patients who had basaloid variant and perineural invasion. For patients with >T3 tumors, local recurrence was higher in patients treated with globe preserving surgery compared to those who underwent orbital exenteration and radiotherapy. Earlier studies by Wright, Rose, and Garner on 38 patients from Moorfields Eye Hospital in London,[2] and Font, Smith, and Bryan on 21 patients with adenoid cystic carcinoma seemed to also favor aggressive surgical intervention with radiotherapy.[3] Ahmed and Esmaeli attempted to distinguish more advanced tumors from less invasive tumors, and although the study was less conclusive for <T3 tumors, globe preserving surgery with radiotherapy seemed to provide local and regional control.

In cases of advanced tumors with high risk of recurrence, neoadjuvent intraarterial chemotherapy with cisplatin and doxorubicin has been used with exenteration and irradiation. In a small study by Tse et al comparing additional intraarterial cytoreductive chemotherapy in 9 patients compared to conventional surgery and radiotherapy, the study concluded that the 5-year carcinoma specific death rate (16.7% compared with 57.1% respectively) and recurrence rate (23.8% compared with 71.4% respectively) was significantly lower in patients treated with intraarterial cytoreductive chemotherapy.[4] Although adjuvant chemoradiation is often routinely employed in other head and neck tumors, there is limited data on the efficacy of this modality in adenoid cystic carcinoma of the lacrimal gland.

In cases where minimal residual tumor remains after surgical intervention, brachytherapy with iodine-125 (I-125) plaques has also been used. In a small study by Shields et al of 4 patients with microscopic residual tumor after excision, brachytherapy with I-125 plaques with a target dose of 50 Gray was applied.[5] Of the 4 patients, 3 had tumor control while one patient required exenteration for recurrence separate from the area of treatment.

Although promising initial data, there is currently insufficient conclusive data on this modality of treatment.

Fig. 5: American Joint Committee on Cancer Classification of Carcinoma of the Lacrimal Gland.

Follow up

Careful follow-up is critical in patients diagnosed with adenoid cystic carcinoma given the tendency for local and regional recurrence and metastasis despite aggressive treatment.

Prognosis

Adenoid cystic carcinoma has a poor overall prognosis, compounded by the limited number of studies available given the rarity of the entity and lack of consensus in treatment approach.

Literature has cited predictors for prognosis including basaloid variant, tumor stage, perineural invasion, age, and presence of apoptotic markers. The often cited study by Gamel and Font indicated a 5-year survival rate for basaloid variant was only 21% as compared to other variants where the survival rate was 71%.[6] Similar findings have been noted in subsequent studies. Multiple studies have also concluded that more advanced tumors, especially with neural invasion results in a poorer prognosis with higher likelihood of recurrence and metastasis even with invasive treatment. However, in one case by Tellado et al, 11 cases of adenoid cystic carcinoma in patients 18 years or younger demonstrated that younger patients had a better prognosis possibly due to less aggressive histology including less basaloid variant and less perineural invasion.[7] In another study by Strianese, the presence of apoptotic markers with down-regulation of p53 and up-regulation of Bcl-2 was also associated with worse prognosis and survival rates.[8]

Additional Resources

- http://www.oculist.net/downaton502/prof/ebook/duanes/pages/v9/v9c017.html#orbi

- http://www.images.missionforvisionusa.org/anatomy/2006/08/what-is-adenoid-cystic-carcinoma-of.html

References

- ↑ Ahmad SM, Esmaeli B, Williams M, et al. American Joint Committee on Cancer classification predicts outcome of patients with lacrimal gland adenoid cystic carcinoma. Ophthalmology 2009 Jun; 116(6): 1210-15.

- ↑ Wright JE, Rose GE, Garner A. Primary malignant neoplasms of the lacrimal gland. Br J Ophthalmol 1992 Jul; 76(7): 401–7.

- ↑ Font RL, Smith SL, Bryan RG. Malignant epithelial tumors of the lacrimal gland: a clinic-pathologic study of 21 cases. Arch Ophthalmol. 1998 May; 116(5): 613-16.

- ↑ Tse DT, Benedetto P, Dubovy S et al. Clinical analysis of the effect of intraarterial cytoreductive chemotherapy in the treatment of lacrimal gland adenoid cystic carcinoma. Am J Ophthalmol 2006 Jan; 141:44-53.

- ↑ Shields JA, Shields CL, Freire JE et al. Plaque Radiotherapy for Selected Orbital Malignancies: Preliminary Observations: The 2002 Montgomery Lecture, Part 2. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003 Mar;19(2):91-5.

- ↑ Gamel JW, Font RL. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the lacrimal gland: the clinical significance of a basaloid histologic pattern. Human Pathol 1982 Mar; 13(3): 219-25.

- ↑ Tellado MV, McLean IW, Specht CS, Varga J. Adenoid cystic carcinomas of the lacrimal gland in childhood and adolescence. Ophthalmology 1997 Oct; 104(10): 1622–5.

- ↑ Strianese D, Baldi G, Staibano S, et al. Expression of apoptosis-related markers in malignant epithelial tumors of the lacrimal gland and their relation to clinical outcome. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007 Sept; 91(9): 1239-43.

- Bartley G, Harris GJ. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the lacrimal gland: Is there a cure…yet? Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002 Sep;18(5):315-8.

- Bernardini FP, Devoto MH, Croxatto JO. Epithelial tumors of the lacrimal gland: an update. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2008 Sep; 19(5): 409-13.

- Esmaeli B, Ahmadi MA, Youssef A et al. Outcomes in Patients with Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma of the Lacrimal Gland. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004 Jan;20(1):22-6.

- Esmaeli B. Golio D, Kies M, DeMonte F. Surgical management of locally advanced adenoid cystic carcinoma of the lacrimal gland. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006 Sep-Oct;22(5):366-70.

- Shields JA, Shields CL, Epstein JA, Scartozzi R, Eagle RC. Primary epithelial malignancies of the lacrimal gland: The 2003 Ramon L. Font Lecture. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004 Jan; 20(1): 10-21.