Acanthamoeba Keratitis

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

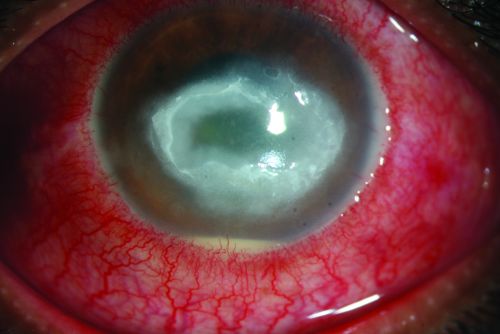

Acanthamoeba keratitis.

Disease

Acanthamoeba keratitis, first recognized in 1973, is a rare, vision threatening, parasitic infection seen most often in contact lens wearers. It is often characterized by pain out of proportion to findings and the late clinical appearance of a stromal ring-shaped infiltrate. It is both difficult to diagnose and difficult to treat.

Etiology and Incidence

Two of the eight known species of Acanthamoeba, A. castellanii and A polyphaga, are responsible for most infections. Acanthamoeba are commonly found, free-living amoeba that have been located in various environments including pools, hot tubs, tap water, shower water, and contact lens solution. In May, 2007, the FDA announced an outbreak of Acanthamoeba keratitis that was associated with Complete MoisturePlus Multi Purpose Solution manufactured by Advanced Medical Optics.

Risk Factors

Risk factors include contact lens wear, exposure to organism (often through contaminated water), and corneal trauma. Low levels of anti-Acanthamoeba IgA in tears has also been shown to be a risk factor. It is thought that over 80% of Acanthamoeba keratitis appears in contact lens wearers. In one study, 75% of the patients were contact lens wearers; 40% wore daily soft lenses, 22% wore rigid gas permeable lenses, and 38% wore extended wear or other lenses. In another case control study of 83 Acanthamoeba keratitis cases and 122 controls, daily-wear reusable lens users were at a three-fold higher risk of developing acanthamoeba keratitis as daily disposable lens users. [1]

General Pathology and Pathophysiology

Acanthamoeba is ubiquitous. Corneal trauma, followed by exposure to the parasite (often through a water supply or contact lens solution) in a patient with low tear levels of anti-Acanthamoeba IgA leads to infection. Acanthamoeba exist in two forms: trophozoites and cysts. The trophozoites are mobile and consume bacteria (which allows for the diagnosis on E. coli plates). The trophozoites form double walled cysts which are incredibly resistant to methods of eradication (including freezing, heating, and irradiation).

The American Academy of Ophthalmology's Pathology Atlas contains a virtual microscopy image of Acanthamoeba Keratitis.

Primary prevention

Since treatment is toxic, lengthy, and not necessarily effective, prevention is essential. Contact lens wearers should be taught how to clean their contact lenses properly. They should be instructed never to use tap water or even saline to clean their lenses. They should also be instructed to visit an ophthalmologist at the earliest sign of problems.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of Acanthamoeba keratitis is difficult and often delayed. Because the currently available treatments for Acanthamoeba are both toxic and lengthy, accurate diagnosis is essential. Diagnostic procedures usually begin with culture. The involved area of cornea can be scraped with a sterile instrument (blade, spatula, needle, calcium alginate swab, or cotton tip applicator) under topical anesthesia at the slit lamp. The culture specimen can then be inoculated into a dish of E. coli plated over non-nutrient agar. Since the clinical picture is often non-specific and co infections are not uncommon[2], cultures should be taken for bacterial, fungal, and viral infections as well. Acanthamoeba trophozoites and cysts can also be identified with the help of Gram, Giemsa-Wright, hematoxylin and eosin, periodic acid-Schiff, calcoflour white, KOH wet mount, or other stains. If available, Confocal microscopy or polymerase chain reaction are testing modalities that may be performed[3][4]. If culture or PCR results are negative or if the lesion is primarily intrastromal and epithelialized, a small corneal biopsy may be considered.

History

Patients should be asked about contact lens wear and hygiene, contact lens solutions, recent corneal trauma, and recent exposure to water sources.

Physical examination

A comprehensive eye exam should be performed with careful attention to the signs and symptoms described below.

Signs

Early signs may be mild and non-specific. Possible findings include epithelial irregularities, epithelial or anterior stromal infiltrates, and pseudodendrites. Later signs include deep stromal infiltrates (ring-shaped, disciform, or nummular), corneal perforation, satellite lesions, persistent epithelial defects, radial keratoneuritis, scleritis, and anterior uveitis with hypopyon, peripheral anterior synechiae and iris atrophy and secondary glaucoma. Advanced signs include stromal thinning and corneal perforation.

Symptoms

Acanthamoeba keratitis is characterized by pain out of proportion to findings. In one study, 95% of patients complained of pain. Patients may also complain of decreased vision, redness, foreign body sensation, photophobia, tearing, and discharge. Symptoms may wax and wane; they may be quite severe at times.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for Acanthamoeba in its early clinical stages includes herpes simplex keratitis, recurrent corneal erosion, staphylococcal marginal keratitis, and contact lens associated keratitis. The differential diagnosis of later clinical stages includes viral, bacterial, fungal, and sterile (such as from topical anesthetic abuse) keratitis. Polymicrobial infection may also occur.

Management

Medical therapy

Medical treatment for Acanthamoeba keratitis is still evolving. Success has been reported with various combinations of antibiotic, antiviral, antifungal, and antiparasitic drugs. Different regimens include combinations of diamidines, biguanides, antibiotics and antifungals, but the most frequently used drug are biguanides as mono therapy or in combination with a diamidine. Some topical preparations of diamidines are propamidine-isethionate, hexamidine-diisethionate, and dibromopropamidine. Biguanides include polyhexamethylene biguanide (PHMB) and chlorhexidine. Neomycin-polymyxin B-gramicidin is thought to kill bacteria which provides a food source for the acanthamoeba. Antifungals include topical and oral preparations of voriconazole as well as ketoconazole, miconazole and clotrimazole . Voriconazole monotherapy was shown to be as effective as PHMB 0.02% and chlorhexidine 0.02% combination therapy in a small prospective, double-masked randomized comparative study (n=18) [5]. Oral miltefosine has been used more recently in refractory cases of Acanthamoeba keratitis[6] with resolution of disease. Severe inflammatory responses following adjuvant therapy with miltefosine has been reported[6][7][8]. Monotherapy with PHMB 0.08% was found to be as effective as dual therapy with PHMB 0.02% and propamidine 0.1% with cure rates of 86% in a RCCT[9]. Steroids are controversial and may worsen the condition by inhibiting the host immune response and are unnecessary in most cases of Acanthamoeba keratitis. However, steroid drops can have a beneficial role in selected cases with persisting inflammation. In such cases, topical steroids can be used only if started after anti-amoebic treatment has completed at least 2-3 weeks and anti-amoebic therapy needs to be maintained throughout and continued after steroids have been withdrawn[9][10]. Pain should be addressed.

Medical follow up

Patients should be followed very closely (daily or almost daily) initially, until clinical response is seen or progression of the disease is blunted. Since recurrences can occur and Acanthamoeba cysts are so resistant to treatment, medical treatments should be tapered very slowly and, if necessary, continued for many months.

Surgery

Cases of corneal perforation may need to be managed with surgical interventions. Conjunctival flap and amniotic membrane have been used with varying success[11]. The recent use of collagen crosslinking in the treatment of acanthamoeba keratitis has demonstrated variable outcomes[12][13]. If possible, penetrating keratoplasty should be reserved for cases of visually significant corneal scarring in quiet eyes. If there are still signs of active infection, medical therapy for Acanthamoeba should resume after keratoplasty, as cysts may linger in the cornea and cause recurrent infection in the graft.

Surgical follow up

Patient should be followed closely at first to monitor for signs of recurrent infection.

Complications

Post-operative complications after penetrating keratoplasty include recurrence of Acanthamoeba infection as well as all of the other possible post-operative complications (such as infection, glaucoma, cataract, wound leak, rejection, astigmatism).

Prognosis

The prognosis for Acanthamoeba is worse than for many other types of infectious keratitis and prevention is therefore very important. However, especially if caught early before the onset of stromal disease, satisfactory outcomes can certainly be achieved.

Additional Resources

- Turbert D, Huffman JM. What Is a Corneal Ulcer (Keratitis)? American Academy of Ophthalmology. EyeSmart/Eye health. https://www.aao.org/eye-health/diseases/corneal-ulcer. Accessed March 01, 2023.

References

- ↑ Carnt N, Minassian DC, Dart JKG. Acanthamoeba Keratitis Risk Factors for Daily Wear Contact Lens Users: A Case-Control Study. Ophthalmology. 2023 Jan;130(1):48-55.

- ↑ Raghavan A, Baidwal S, Venkatapathy N, Rammohan R. The Acanthamoeba-Fungal Keratitis Study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2019 May;201:31-36. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2019.01.024. Epub 2019 Feb 2. PMID: 30721687.

- ↑ Parmar D, Awwad S, Petroll Mm Bowman W, McCulley J, Cavanagh D: Tandem Scanning Confocal Corneal Microscopy in the Diagnosis of Suspected Acanthamoeba Keratitis. Ophthalmology 113(4); 538-547, 2006

- ↑ Biology 2023, 12(12), 1489; https://doi.org/10.3390/biology12121489

- ↑ Bagga B, Sharma S, Gour RPS, Mohamed A, Joseph J, M Rathi V, Garg P. A randomized masked pilot clinical trial to compare the efficacy of topical 1% voriconazole ophthalmic solution as monotherapy with combination therapy of topical 0.02% polyhexamethylene biguanide and 0.02% chlorhexidine in the treatment of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Eye (Lond). 2021 May;35(5):1326-1333. doi: 10.1038/s41433-020-1109-4. Epub 2020 Jul 27. PMID: 32719525; PMCID: PMC8182824

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Thulasi P, Saeed HN, Rapuano CJ, Hou JH, Appenheimer AB, Chodosh J, Kang JJ, Morrill AM, Vyas N, Zegans ME, Zuckerman R, Tu EY. Oral Miltefosine as Salvage Therapy for Refractory Acanthamoeba Keratitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2021 Mar;223:75-82. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2020.09.048. Epub 2020 Oct 10. PMID: 33045218.

- ↑ Si Z, Veldman PB, Reidy JJ, Farooq AV. Severe Inflammatory Response in a Patient on Oral Miltefosine for Acanthamoeba Keratitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2021 Feb 9:1-2. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2020.1854315. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 33560165.

- ↑ de la Presa M, Ibach M, Berdahl J, Holland EJ. Anterior Scleral and Limbal Inflammatory Necrosis After Adjuvant Miltefosine for Recalcitrant Acanthamoeba Keratitis. Cornea. 2021 Sep 4. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000002849. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34483272.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Dart, J.K.; Papa, V.; Rama, P.; Knutsson, K.A.; Ahmad, S.; Hau, S.; Sanchez, S.; Franch, A.; Birattari, F.; Leon, P.; et al. The Orphan Drug for Acanthamoeba Keratitis (ODAK) Trial: PHMB 0.08% (Polihexanide) and Placebo versus PHMB 0.02% and Propamidine 0.1. Ophthalmology, 2023 Oct 5:S0161-6420(23)00710-8. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2023.09.031

- ↑ Am J Ophthalmol. 2009 Oct;148(4):487-499.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2009.06.009

- ↑ Abdulhalim BE, Wagih MM, Gad AA, Boghdadi G, Nagy RR. Amniotic membrane graft to conjunctival flap in treatment of non-viral resistant infectious keratitis: a randomised clinical study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015 Jan;99(1):59-63. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2014-305224. Epub 2014 Jul 22. PMID: 25053758.

- ↑ Papaioannou L, Miligkos M, Papathanassiou M. Corneal Collagen Cross-Linking for Infectious Keratitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cornea. 2016 Jan;35(1):62-71. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000000644. PMID: 26509768.

- ↑ Ting DSJ, Henein C, Said DG, Dua HS. Photoactivated chromophore for infectious keratitis - Corneal cross-linking (PACK-CXL): A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ocul Surf. 2019 Oct;17(4):624-634. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2019.08.006. Epub 2019 Aug 8. PMID: 31401338.

- Krachmer J, Mannis M, Holland E: CORNEA, 2nd ed.Elsevier Mosby, 2005, 1115-1122.

- Ocular Pathology Atlas. American Academy of Ophthalmology Web site. https://www.aao.org/resident-course/pathology-atlas. Published 2016. Accessed January 4, 2017