Marginal Keratitis

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Marginal Keratitis - ICD-10 H16.39 (Other Interstitial and Deep Keratitis)

Other names: Staphylococcal Marginal Keratitis; Catarrhal infiltrates.

Disease

Marginal keratitis is an inflammatory disease of the peripheral cornea, characterized by peripheral stromal infiltrates which are often associated with epithelium break down and ulceration. It is usually associated with the presence of blepharoconjunctivitis and is thought to represent an inflammatory response against S. aureus antigens.[1]

Etiology and pathophysiology

The vast majority of patients with marginal keratitis have symptomatic Staphylococcal blepharitis/conjunctivitis, or asymptomatic Staphylococcal colonization of the eyelid.[1]

Marginal keratitis is thought to be the product of an inflammatory reaction against staphylococcal antigens (rather than a direct staphylococcal infection of the cornea). The presence of bacterial antigens in the peripheral area of the cornea possibly triggers a type III hypersensitivity reaction, in which immunocomplexes are formed and deposited in the peripheral corneal stroma.[2] There are subsequent complement pathway activation and neutrophil attraction, with the formation of a peripheral stromal opacity also called catarrhal infiltrate. This lesion may evolve with epithelial damage, forming a marginal ulcer.

The role of Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) and myeloid differentiation factor 88 (MyD88) in mediating this inflammatory response has been highlighted, indicating that these pathways are crucial for the recruitment of neutrophils and the production of inflammatory cytokines in response to S. aureus.[3] [4]

The lesions usually appear in areas of direct contact between the peripheral cornea and the eyelid margin, which substantiates the relationship between the keratitis and S. aureus colonization.[1]

Besides the spatial relationship, it is hypothesized that marginal keratitis is the product of anatomical and chemical variations between the central and peripheral cornea. The distance between the central cornea and limbal blood vessels slows down the diffusion of high molecular weight proteins, like IgM and C1 protein, which occur at higher concentrations in the peripheral cornea. The peripheral cornea also has a higher concentration of Langerhans Cells. Therefore, it has been hypothesized that a circular zone of the cornea that is 1 to 2 mm from the limbus may have an antigen-to-antibody ratio that is conducive to larger, more inflammogenic immune complexes. The distance between the central cornea and limbus also means a reduced contact between central cornea antigens and the afferent arm of the immune system, which may protect the central cornea from immune-mediated injury.[5]

Recent studies have also explored the role of staphylococcal superantigens and phenol-soluble modulins (PSMs) in the pathogenesis of corneal inflammation. While superantigens are unlikely to play a central role in marginal keratitis, PSMs have been shown to induce significant corneal inflammation through the release of alarmins and the activation of IL-36-dependent pathways. [6]

Risk Factors and Primary Prevention

The major risk factor is the presence of longstanding blepharitis, conjunctivitis, or meibomitis. In the vast majority of cases, the presence of catarrhal infiltrates is associated with Staphylococcal blepharoconjunctivitis although other microorganisms have been previously isolated from the eyelid of marginal keratitis patients, such as Haemophilus, Moraxella or Streptococcus.[7] [8]

Management of the underlying cause, i.e. blepharitis, is the main form of prevention of marginal keratitis.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of marginal keratitis is usually based on patient history and slit-lamp examination findings. Ancillary testing can be useful, especially in atypical cases or in cases with peripheral ulceration, in which other diagnoses need to be ruled out.[1]

Symptoms

Patients with marginal keratitis present with mild, nonspecific symptoms like pain, foreign body sensation, photophobia, and conjunctival injection.

Physical examination

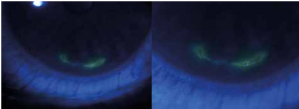

The disease usually begins with the formation of one or more stromal infiltrates in the peripheral cornea, typically in the points of intersection between the eyelid margin and the limbus (i.e. 2, 4, 8, and 10 o’clock positions). These infiltrates are almost always located 1-2mm parallel to the limbus, with a clear margin of healthy cornea between them. The lesions can spread and coalesce circumferentially, with little tendency to grow centrally or peripherally. With prolonged inflammation, there can be an epithelial lesion, leading to the formation of a marginal ulcer.[1][5]

Since the majority of cases are related to symptomatic blepharoconjunctivitis, its distinctive features can also be observed. Erythema and edema of the eyelid margin associated with telangiectasias are common findings in all forms of blepharitis. Eyelash changes like madarosis, poliosis, trichiasis, and the presence of hard scales in the base of eyelashes, are more specific findings of the long-standing S. aureus blepharitis. In more severe cases, the removal of these scales from the eyelid margin can cause ulceration.[9]

Diagnostic procedures

The diagnosis of marginal keratitis is primarily clinical, characterized by peripheral stromal infiltrates with a 1-2mm clear corneal margin, often associated with blepharitis. In typical cases, no additional diagnostic procedures are necessary. However, when an epithelial defect is present, it is crucial to distinguish marginal keratitis from other forms of ulceration, particularly infectious ulceration.

In such cases, corneal scrape cultures can be useful. According to the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Society for Microbiology, corneal scrapings should be obtained and inoculated directly onto culture plates at the patient's bedside. These plates, including sheep blood agar and chocolate agar, should be transported immediately to the microbiology laboratory for incubation and analysis. [10] This approach helps identify bacterial, fungal, or viral pathogens that may be responsible for the ulceration.

In summary, while typical cases of marginal keratitis do not require extensive diagnostic procedures, the presence of an epithelial defect necessitates corneal scrape cultures to rule out infectious causes and guide appropriate treatment.[1][10]

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of marginal keratitis includes various causes of peripheral stromal keratitis and peripheral ulcerative keratitis (PUK). It is essential to distinguish marginal keratitis from other conditions due to differences in management and prognosis.

Bacterial Corneal Ulcers: These typically present more centrally and tend to progress both centrally and peripherally. They are often associated with significant pain, purulent discharge, and a more aggressive clinical course. Corneal scrape cultures are essential for identifying the causative organism and guiding antibiotic therapy. [10]

Herpetic stromal keratitis: This can be indistinguishable from marginal keratitis initially. However, herpetic keratitis usually starts with an epithelial defect that evolves into a stromal lesion, whereas marginal keratitis starts with a stromal lesion. Herpetic keratitis is also associated with corneal hypoesthesia, which is not seen in marginal keratitis. Diagnosis can be confirmed with polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing for herpes simplex virus (HSV). [11]

Peripheral ulcerative keratitis associated with collagen-vascular disorders can mimic marginal keratitis but is often associated with systemic diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, and systemic lupus erythematosus. PUK is typically more severe, often associated with scleritis, and less responsive to topical steroids. Multidisciplinary management involving rheumatologists and the use of systemic immunosuppressive therapy is often required. [12] [13]

Mooren ulcer is a form of idiopathic peripheral ulcerative keratitis, which can be very similar to marginal keratitis but does not spare the limbal margin and can be more aggressive. It is characterized by progressive peripheral corneal thinning and ulceration, often requiring surgical intervention in addition to medical therapy. [14]

Management

The primary goal of treatment is to reduce local inflammation and reduce the risk of future flares by reducing staphylococcal antigens at the eyelid margins and corneal surface.

Medical therapy

In cases of marginal keratitis with peripheral stromal infiltrates without epithelial defects, topical corticosteroids are effective in reducing local inflammation. Commonly used corticosteroids include prednisolone acetate 1%, loteprednol 0.5%, and fluorometholone 0.1%. These agents help control inflammation and prevent scarring. The use of corticosteroids should be closely monitored to avoid potential side effects such as elevated intraocular pressure and cataract formation. [15]

In those cases where an epithelial defect is present, steroids should be used judiciously, combined with a broad-spectrum antibiotic, and with close monitoring. When an epithelial defect is present, it is crucial to distinguish marginal keratitis from infectious keratitis. In such cases, corneal scrape cultures are recommended to identify any infectious agents. If an infection is confirmed, appropriate antimicrobial therapy should be initiated. Topical antibiotics such as moxifloxacin or gatifloxacin are typically used for bacterial infections. Once the infection is controlled, corticosteroids can be cautiously introduced to manage inflammation, ensuring that the antimicrobial therapy is effective in clearing the infection. [16]

Effective management of underlying blepharitis is essential to prevent recurrence of marginal keratitis. Key strategies include:

1. Eyelid Hygiene: Regular eyelid hygiene with warm compresses and eyelid scrubs helps reduce bacterial load and improve meibomian gland function.

2. Topical Antibiotic Ointments: Topical antibiotics such as erythromycin or bacitracin ointment can be applied to the eyelid margins to reduce bacterial colonization.

3. Oral Antibiotics: For severe or refractory cases, oral antibiotics like doxycycline (50-100 mg twice daily) or azithromycin (500 mg once daily for 3 days) are used for their anti-inflammatory properties. [17]

4. Short Courses of Topical Steroids: Short courses of topical steroids can be used to control acute inflammation associated with blepharitis. Agents such as loteprednol 0.5% are preferred due to their lower risk of side effects.

Surgery

There is no surgical treatment available targeting the primary disease.

Prognosis

The natural course of the disease is spontaneous resolution in two to three weeks, with few to no long-term sequelae such as anterior stromal scarring. Recurrences are common, especially if the concomitant blepharitis is not treated.

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Mannis M., Holland E.: Cornea. Elsevier Health Sciences. 2016; 1079-1081.

- ↑ Smolin G. Hypersensitivity reactions. In: Smolin G, editor. Ocular immunology. 2nd ed. Boston: Little, Brown; 1986

- ↑ Sun Y, Hise AG, Kalsow CM, Pearlman E. Staphylococcus aureus-induced corneal inflammation is dependent on Toll-like receptor 2 and myeloid differentiation factor 88. Infect Immun. 2006 Sep;74(9):5325-32.

- ↑ Marino A, Pergolizzi S, Lauriano ER, Santoro G, Spataro F, Cimino F, Speciale A, Nostro A, Bisignano G. TLR2 activation in corneal stromal cells by Staphylococcus aureus-induced keratitis. APMIS. 2015 Feb;123(2):163-8.

- ↑ Jump up to: 5.0 5.1 Mondino BJ. Inflammatory disease of the peripheral cornea. Ophthalmology 1988;95:463–72.

- ↑ Nakajima I, Fukuda K, Ishida W, Kishimoto T, Kuwana A, Suzuki T, Kaito C, Yamashiro K. Staphylococcus aureus-derived virulent phenol-soluble modulin α triggers alarmin release to drive IL-36-dependent corneal inflammation. Microbes Infect. 2024 Jan-Feb;26(1-2):105237.

- ↑ Cohn H, Mondino BJ, Brown SI, et al. Marginal corneal ulcers with acute beta streptococcal conjunctivitis and chronic dacryocystitis. Am J Ophthalmol 1979;87:541–3.

- ↑ Rocha KM, Farid M, Raju L, Beckman K, Ayres BD, Yeu E, Rao N, Chamberlain W, Zavodni Z, Lee B, Schallhorn J, Garg S, Mah FS; From the ASCRS Cornea Clinical Committee. Eyelid margin disease (blepharitis and meibomian gland dysfunction): clinical review of evidence-based and emerging treatments. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2024 Aug 1;50(8):876-882.

- ↑ McCulley JP, Dougherty JM, Deneau DG. Classification of chronic blepharitis. Ophthalmology 1982;89:1173.

- ↑ Jump up to: 10.0 10.1 10.2 Miller JM, Binnicker MJ, Campbell S, Carroll KC, Chapin KC, Gilligan PH, Gonzalez MD, Jerris RC, Kehl SC, Patel R, Pritt BS, Richter SS, Robinson-Dunn B, Schwartzman JD, Snyder JW, Telford S 3rd, Theel ES, Thomson RB Jr, Weinstein MP, Yao JD. A Guide to Utilization of the Microbiology Laboratory for Diagnosis of Infectious Diseases: 2018 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Society for Microbiology. Clin Infect Dis. 2018 Aug 31;67(6):e1-e94.

- ↑ Praidou A, Androudi S, Kanonidou E, Konidaris V, Alexandridis A, Brazitikos P. Bilateral herpes simplex keratitis presenting as peripheral ulcerative keratitis. Cornea. 2012 May;31(5):570-1.

- ↑ Gupta Y, Kishore A, Kumari P, Balakrishnan N, Lomi N, Gupta N, Vanathi M, Tandon R. Peripheral ulcerative keratitis. Surv Ophthalmol. 2021 Nov-Dec;66(6):977-998.

- ↑ Sura AA, McCallum RM. Peripheral ulcerative keratitis due to systemic diseases. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2022 Nov 1;33(6):543-550.

- ↑ Sharma N, Sinha G, Shekhar H, Titiyal JS, Agarwal T, Chawla B, Tandon R, Vajpayee RB. Demographic profile, clinical features and outcome of peripheral ulcerative keratitis: a prospective study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015 Nov;99(11):1503-8.

- ↑ Sharma B, Soni D, Mohan RR, Sarkar D, Gupta R, Chauhan K, Karkhur S, Morya AK. Corticosteroids in the Management of Infectious Keratitis: A Concise Review. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2021 Oct;37(8):452-463.

- ↑ Austin A, Lietman T, Rose-Nussbaumer J. Update on the Management of Infectious Keratitis. Ophthalmology. 2017 Nov;124(11):1678-1689.

- ↑ Dang DH, Riaz KM, Karamichos D. Treatment of Non-Infectious Corneal Injury: Review of Diagnostic Agents, Therapeutic Medications, and Future Targets. Drugs. 2022 Feb;82(2):145-167.