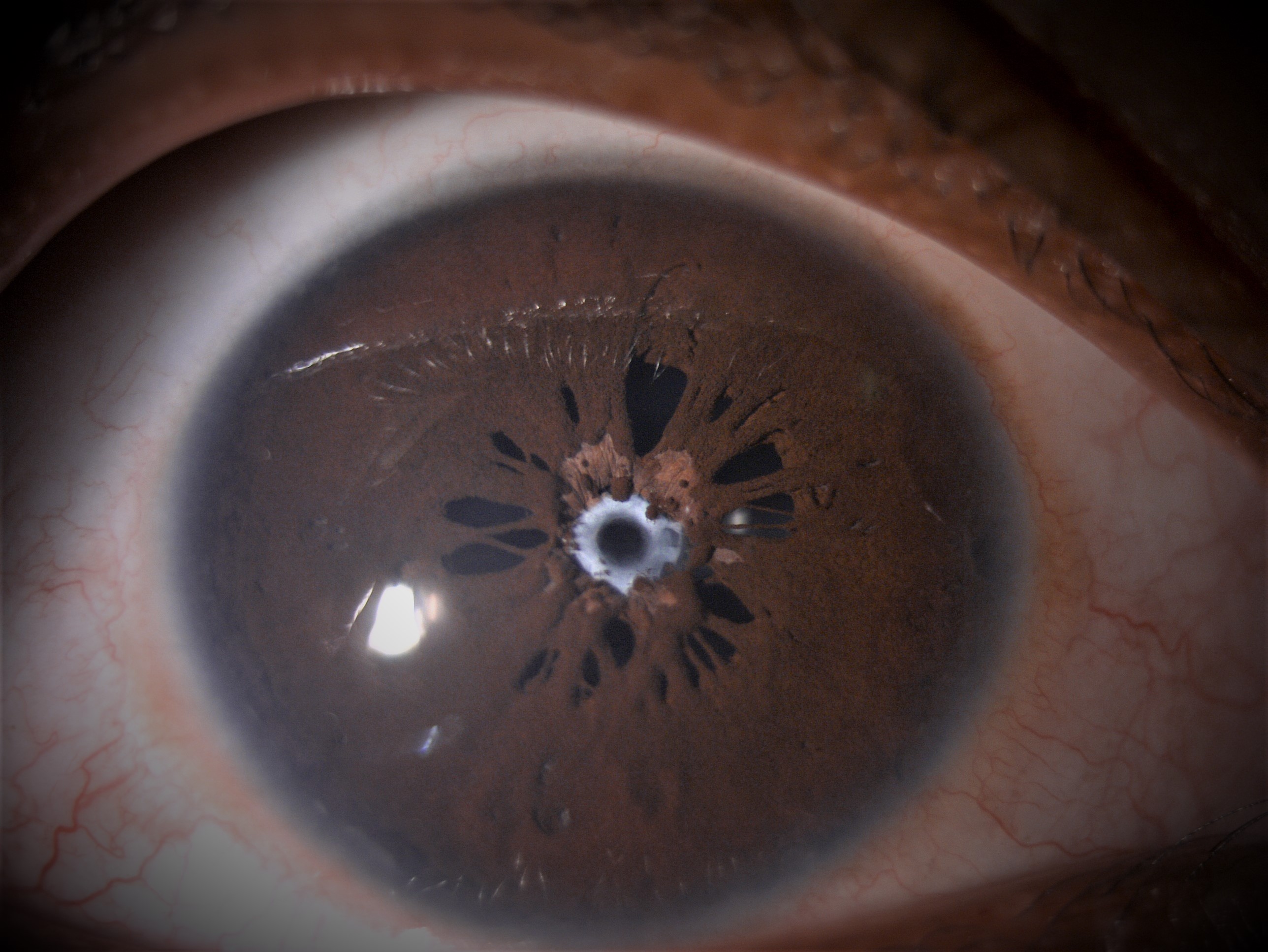

Persistent Pupillary Membrane

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Disease

Persistent pupillary membrane(PPM) is a frequently encountered congenital anomaly. It represents remnants of anterior tunica vasculosa lentis and appears as strands of connective tissue bridging the pupillary area. They are usually asymptomatic and of no functional significance. In rare cases, dense membranes can persist and obscure the pupil, causing amblyopia.

Etiology

Although familial forms have been reported, most cases are sporadic in nature.[1]

Pathophysiology

Persistent pupillary membrane represents remnants of anterior tunica vasculosa lentis. Embryologically, the iris forms as a solid sheet of mesodermal tissue known as the pupillary membrane. It is composed of vessels derived from anterior ciliary arteries and mesenchyme and lies ventral to the lens. The dorsal posterior hyaloid vessels anastomose with the network of vessels in the pupillary membrane to form tunica vasculosa lentis which provides nutrition to the lens. The pupillary membrane undergoes regression aided by macrophage phagocytosis in the sixth month and disappears completely by the eighth month of gestation.[2] A failure of resorption of pupillary membrane leads to persistent pupillary membrane. There is evidence that intrauterine stress, particularly from chronic maternal hypertension, may accelerate the disappearance of these membranes.[3] Postnatal PPM undergoes considerable atrophy in the first year of life.

Incidence

The remnants of pupillary membrane are seen in about 95% of neonates and 20% of adults. They are more common in premature babies. There is no sex predilection and may present unilaterally or bilaterally.

Diagnosis

Classification

Duke-Elder has Classified PPM into several variants[4]

- Type 1 membranes that are attached solely to the iris

- Type 2 membranes are iridolenticular adhesions. In a sub-variant of type 2, pigmented dendritic iris stromal melanocytes, singly and in clumps, are situated aberrantly on the anterior lens capsule. These pigmented stars of the anterior lens capsule are often called “chicken tracks”.

- Type 3 membranes, which are attached to the cornea, typically occur in Axenfeld-Rieger syndrome. Pure capsular opacities associated with persistent pupillary membranes or epicapsular stars are very rare. They are congenital in origin, do not affect vision and may be nonaxial.

Symptoms

PPMs are usually asymptomatic except for cases with a pupillary opening of <1.5 mm in which decreased retinal illumination and diffraction results in impaired vision.[5]

Signs

Slit lamp appearance of PPM can be variable. Most of the times, it can be seen as single or several lacy strands that partially bridge the pupil. The peripheral portion always inserts into the iris collarette. The central portion may attach to the anterior lens capsule or float with free edges. Iris melanocytes may be observed on the anterior lens capsule forming "pigment stars" or "chicken tracks". Infrequently, extensive sheet of iris membrane occluding the pupil may occur.Rare cases of hyphaema from a strand of PPM have been reported.Rarely, progressive pupillary occlusion may be seen with late angle closure glaucoma.

Investigations

Diagnosis is clinical. Other tests to be performed are:

Retinoscopy- Lenticular astigmatism if focal lens opacity is present

High frequency ultrasound in extensive membranes may be helpful to evaluate relationship of membranes to lens capsule

Iris angiography- Only 0.3% demonstrate vascular perfusion. Most membranes do not justify assessment with fluorescein angiography.

Associations

Associations with PPM include amblyopia, coloboma, anterior polar cataract, strabismus, and anterior segment abnormalities like microcornea, microphthalmos and corneal opacity.

Differential Diagnosis

- Post inflammatory synechiae

- Accessory Iris membrane (AIM)- also called iris duplication, closely resembles the normal iris tissue in color and thickness and presents a virtual second pseudopupil aperture in the centre.[6]

- Congenital idiopathic microcornia

Treatment

During the first year of life, most PPMs undergo atrophy and require no treatment. Membranes persisting after one year are less likely to regress spontaneously, increasing the risk of derivational amblyopia. A 1.5-mm pupillary opening is necessary for adequate retinal stimulation and visual cortex development. Management of PPMs depends on the extent of the membrane, and consequently the size of the pupillary opening.

Small PPMs can be managed conservatively. Mydriatics, refractive correction, and patching for amblyopia have been used successfully in such cases.[7]

Thick, fibrotic membranes may require surgical excision.[8] [9] Surgery is generally performed in the first weeks or months of life, with good visual prognosis and consists of excision of the pupillary membrane using Vannas or vitreous scissors and capsule forceps for gentle removal. Surgical management comes with risks typical of intraocular surgery including cataract formation in a young patient. Therefore, a careful risk/benefit analysis must be performed. If not visually limiting/amblyogenic, conservative management is often preferred.

Older patients with thin, sparse membranes may be candidates for Nd:YAG laser membrane lysis.[10] Photodisruption of membrane can rarely lead to hyphaema. The procedure also carries the risk of cataract formation, iritis, and pigment dispersion.

Additional Resources

- American Academy of Ophthalmology. Congenital and Developmental Anomalies of the Iris or Pupil. Basic and Clinical Science Course, Section 6. Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. San Francisco: American Academy of Ophthalmology; 2022-2023:281-282.

References

- ↑ Cassady JR, Light A. Familial Persistent Pupillary Membranes. AMA Arch Ophthalmol. 1957;58(3):438–448.

- ↑ Goldberg MF. Persistent fetal vasculature (PVF): An integrated interpretation of signs and symptoms associated with persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997;124:87–626

- ↑ Hadi HA, Hobbs CL. Effect of chronic intrauterine stress on the disappearance of tunica vasculosa lentis of the fetal eye: A neonatal observation Am J Perinatol. 1990;7:23–5

- ↑ Tasman W, Jaeger E Duane's Ophthalmology. 2007 Philadelphia Lippincott Williams & Wilkins:24–258

- ↑ Miller SD, Judisch GF. Persistent pupillary membrane: successful medical management. Arch Ophthalmol. 1979 Oct;97(10):1911-3.

- ↑ Banigallapati, Shashidhar; Potti, Sudhakar; Marthala, Himabindu A rare case of persistent pupillary membrane, Indian Journal of Ophthalmology: October 2018 - Volume 66 - Issue 10 - p 1480-1483

- ↑ Kurt E. A patient with bilateral persistent pupillary membrane: a conservative approach.J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus2009; 46:300–2.

- ↑ Oner A, Ilhan O, Dogan H. Bilateral extensive persistent pupillary membranes. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus 2007;44:57-58.

- ↑ Kraus CL, Lueder GT. Clinical characteristics and surgical approach to visually significant persistent pupillary membranes. J AAPOS 2014;18:596-9

- ↑ Gupta R, Kumar S, Sonika, Sood S. Laser and surgical management of hyperplastic persistent pupillary membrane Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. 2003;34:136–9