Coloboma

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

ICD-10 Codes

- Coloboma of eyelid: Q10.3

- Coloboma (iris): Q13.0

- Coloboma of eye lens: Q12.2

- Coloboma of optic disc: H47.319

- Coloboma of choroid and retina: Q14.8

- Coloboma of macula: Q14.8

Disease

Coloboma is derived from the Greek koloboma, meaning mutilated, curtailed, or with defect. The term is used to describe ocular defects of the eyelids, iris, lens, ciliary body, zonules, choroid, retina or optic nerve. It is typically located in the inferonasal quadrant of the involved structure and is often associated with microphthalmia. It can affect one eye (unilateral) or both eyes (bilateral).

It is important to differentiate colobomas involving the globe from those of the eyelids. In either case, they can affect one eye (unilateral) or both eyes (bilateral).

Etiology

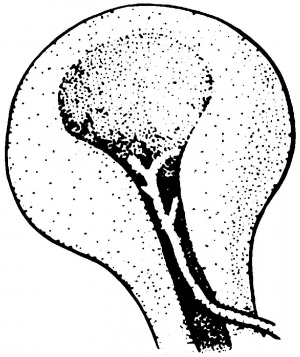

Coloboma of the iris, ciliary body, choroid, retina and/or optic nerve derive from failed or incomplete closure of the embryonic fissure (also known as choroidal or optic fissure) during development. Eye colobomas are located in the inferior nasal quadrant. The embryonic fissure develops from eccentric invagination of the optic vesicle leaving a gap inferonasally. This gap allows the hyaloid artery to access the inner eye and is crucial for continued ocular development. Vitamin A (retinol), which has previously been shown to be crucial for normal eye development,[2] is also thought to be integral to this process.[3][4] In an ocular coloboma animal model in which retinol dehydrogenase is absent, supplementation with retinoic acid allows for normal ocular development.[5]

Closure of the embryonic fissure occurs during the second month of embryonic development. Closure of the fissure begins on day 33 of gestation and allows for pressurization of the globe. The process begins at the equator and proceeds anteriorly and posteriorly. A large spectrum of disease can result from defects in closure ranging from mild and asymptomatic to microphthalmia or even anophthalmia. Defects in closure at either pole have different results. Colobomas of the iris or ciliary body result from failures of complete anterior closure, while colobomas of the choroid, retina or optic nerve result rom failures of posterior closure.[6]

Coloboma of the lens is due to defective or absent development of the zonules in any segment. There is a corresponding flattening of the equator of the lens due to a lack of tension on the lens capsule, which may lead to subsequent contraction and notching in that region. The term ‘lens coloboma’ is therefore a misnomer because the tissue lost in this defect is of the zonules rather than the lens.[7][8]

Coloboma of the eyelid has a different embryologic origin from a coloboma of the globe. Eyelid colobomas are typically located at the superior medial upper eyelid. Lid coloboma arises from defective eyelid development; either during fusion, occurring during the third and fourth months of embryologic development, or during re-separation, which occurs in the sixth or seventh months.[9][10] Although the sequence of eyelid development itself is induced by the developing globe, there is no clear evidence that eyelid coloboma results from globe abnormalities. [11] Coloboma of the eyelid are along the spectrum of craniofacial clefts and can occur either as an isolated malformation or associated with ocular or systemic anomalies.[12][13]

Incidence

Ocular coloboma due to failed closure of the embryonic fissure occurs in 0.5 - 2.2 cases per 10,000 live births. [12] [13] It may be sporadic or inherited and is associated with systemic disorders in some cases.[14]

Eyelid coloboma is estimated to occur in 0.2 - 0.8 cases per 10,000 live births, and likewise may arise de novo or be hereditary. [15]Eyelid colobomas may also occur as isolated defects or as part of a syndromic condition.[9]

Associations

Association with other systemic abnormalities:

There are numerous syndromic and chromosomal abnormalities associated with uveal coloboma including trisomies, duplications, deletions and pericentric inversions.[8]

Specific disorders include:

- 13q deletion syndrome

- Aicardi syndrome

- Basal cell nevus (carcinoma) syndrome

- Catel-Manzke syndrome

- Cat-eye syndrome

- CHARGE Syndrome

- Congenital contractural arachnodactyly

- Humeroradial synostosis

- Kabuki syndrome

- Lenz microphthalmia syndrome

- Linear sebaceous nevus syndrome

- Meckel-Gruber syndrome

- MIDAS syndrome

- Oral-facial-digital syndrome (type VIII)

- Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome

- Sjogren-Larsson syndrome

- Trisomy 13 (Patau syndrome)

- Trisomy 18 (Edwards syndrome)

- Walker-Warburg syndrome

Association with other eye abnormalities or features:

- Cataract

- Difference in eye color between the two eyes (heterochromia)

- Glaucoma

- Increase risk for retinal detachment

- Increased thickness of the cornea

- Involuntary eye movements (nystagmus)

- Nearsightedness (myopia) or farsightedness (hyperopia)

- Poor vision or Visual Field defect

- Posterior staphyloma

- Retinal malformation (retinal dysplasia)

- Small eye (microphthalmia)

Eyelid coloboma are usually found in the upper lid and are often isolated with the exception of an association with Goldenhar syndrome. In contrast, lower eyelid coloboma are often associated with Treacher-Collins Syndrome.[7]

Eyelid coloboma are usually found in the upper lid and are often isolated with the exception of an association with Goldenhar syndrome. In contrast, lower eyelid coloboma are often associated with Treacher-Collins Syndrome.[16]

Physical examination

Physical examination of both the external and internal surfaces of the eyelids may reveal obvious defects which typically may be seen at or soon after birth. Eyelid coloboma, however, can be minimal and may not be appreciated until later in life. (Figure 2)

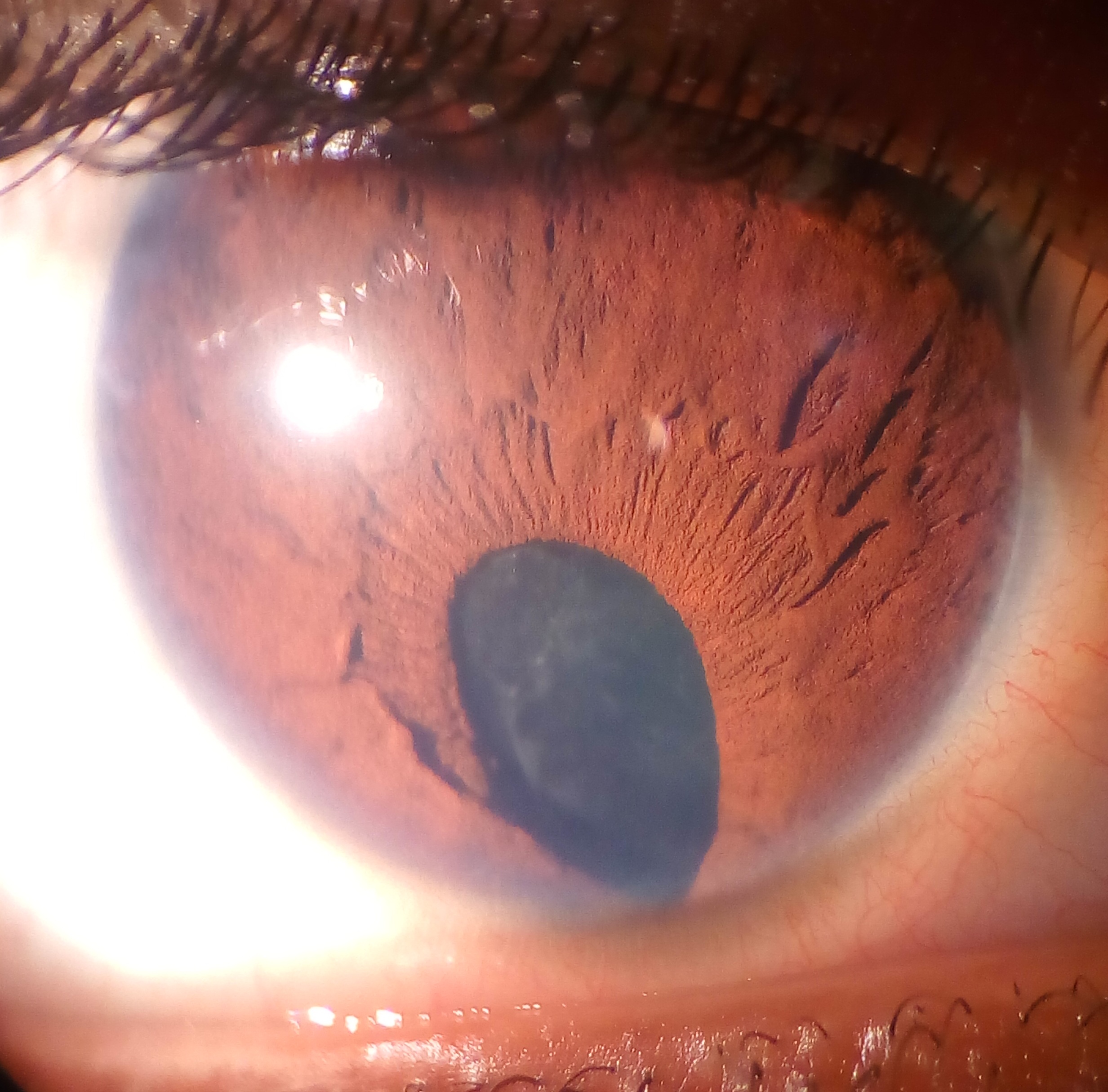

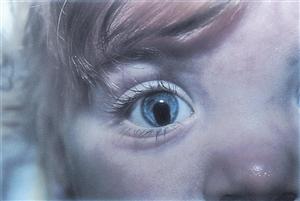

Anteriorly located coloboma often appears as a defect in the iris tissue, in the shape of a keyhole. They are classified as “typical” if found in the inferonasal quadrant of the affected structure and “atypical” if found elsewhere. Cornea, ciliary body and zonules may also be involved. (Figure 4)

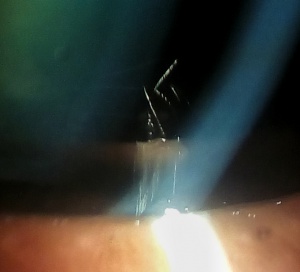

Lens coloboma is seen as flattening of the equator of the lens in an area of absence of zonular fibers. This is best visualized in a dilated eye and may be incidentally diagnosed as they are almost always asymptomatic. (Figure 3)

Figure 2. Coloboma of the upper eyelid. Photo courtesy of AAO.[17] |

Figure 3. Coloboma of the lens. Photo courtesy of AAO.[18] |

Figure 4. Typical coloboma of the iris. Photo courtesy of AAO.[19] |

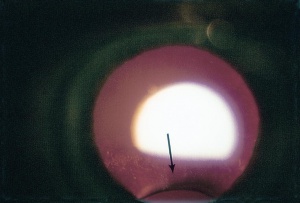

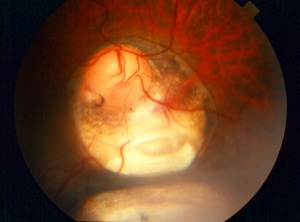

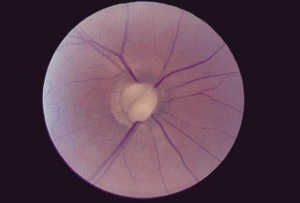

Posteriorly located coloboma can involve the optic nerve, retina, and choroid. If the retina is involved, it is reduced to glial tissue with no underlying RPE or choroid. This appears as an area of whitening often with pigment deposition at the junction of the coloboma and normal retina. If the optic nerve is involved, it can have a range of appearance from physiologic cupping to extensive retinal involvement (as shown in the figure below). The examiner should be wary during initial examination to evaluate for retinal detachment as patients with coloboma have increased risk for this to occur.

Figure 5. Coloboma involving the optic nerve, retina, and choroid in the typical inferonasal quadrants. Photo courtesy of AAO.[20] |

Figure 6. Optic disc coloboma. Photo courtesy of AAO.[21] |

Complications

Retinal detachment and cataract are the most common complications associated with retinochoroidal coloboma. Coloboma of the posterior pole is associated with an increased risk for retinal detachment with occurs in 23-42% of patients.[22]

Cataracts of multiple varieties are associated with coloboma including pigment deposits, subcapsular, cortical, anterior and posterior polar, and total opacification. Lens subluxation has also been reported in cases involving the zonules and or ciliary body. This is also a consideration for a patient undergoing cataract surgery.[7] [8]

Complications of eyelid coloboma are mainly due to corneal exposure from large upper eyelid defects resulting in exposure keratopathy and corneal ulceration if left untreated.[23][24]

Differential Diagnosis

Eyelids

- Congenital amniotic band syndrome

- Eyelid trauma

- Entropion

Iris

- Aniridia

- Heterochromia irides

- Iris nevi

- Iris trauma

- Iris atrophy

- Rieger syndrome

Optic Nerve

- Morning glory disk

- Congenital optic pits

- Optic nerve staphylomata

Retinochoroidal colobomata are usually easy to distinguish from inflammatory lesions and other causes of leukocoria.

Management

Eyelid Coloboma

Lubrication should be supplied if there is any evidence of compromised lid closure and corneal protection. Evaluation by oculoplastics is recommended to determine if and how lid reconstruction should occur.

Lens Coloboma

Refractive error should be treated with corrective lenses. If severe and unable to correct with manifest refraction, consider lens extraction with IOL placement to prevent amblyopia from developing. Care should be taken, however, as zonular abnormalities exist and may complicate surgery.

Chorioretinal Coloboma

The most important predictor of visual outcome is identification of normal foveal anatomy.[25] [26]

Patients with bilateral uveal coloboma or unilateral coloboma plus one other systemic abnormality should be referred to genetics specialist to evaluate for systemic disorders.[7]

Monocular precautions should be strongly considered for any patient with unilateral coloboma and resulting decreased visual acuity on the affected side.

Interval monitoring for retinal detachment should be done with a dilated fundus exam approximately every 6-12 months or sooner if indicated for patients with posterior coloboma. A risk of retinal detachment is there which may be upto 40%. Prophylactic laser of such eyes may reduce the occurrence of retinal detachment[27], though randomized trial for this is not yet available.

Measures such as patching should be taken to maximize visual potential of the affected side as there is often normal retina present and refractive error is often present putting patients at risk for amblyopia.[26]

Additional Resources

- Porter D, Lipsky SN. Coloboma. American Academy of Ophthalmology. EyeSmart/Eye health. https://www.aao.org/eye-health/diseases/coloboma-list. Accessed March 07, 2019.

- National Eye Institute: Facts About Anophthalmia and Microphthalmia - http://www.nei.nih.gov/health/anoph/anophthalmia.asp

- Einstein Healthcare Network: The Anophthalmia Microphthalmia Registry - http://www.einstein.edu/genetic/anophthalmia-microphthalmia-registry/

- The International Children's Anophthalmia Network - http://www.anophthalmia.org/

References

- ↑ Optic cup and stalk with open embryonic fissure below. at <http://one.aao.org/image/optic-cup-stalk-with-open-embryonic-fissure-below-2>

- ↑ Hyatt, G. A. & Dowling, J. E. Retinoic acid. A key molecule for eye and photoreceptor development. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 38, 1471–1475 (1997).

- ↑ Nadauld, L. D. et al. Dual roles for adenomatous polyposis coli in regulating retinoic acid biosynthesis and Wnt during ocular development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103, 13409–13414 (2006).

- ↑ Hornby, S. J., Ward, S. J. & Gilbert, C. E. Eye birth defects in humans may be caused by a recessively-inherited genetic predisposition to the effects of maternal vitamin A deficiency during pregnancy. Med. Sci. Monit. Int. Med. J. Exp. Clin. Res. 9, HY23–26 (2003).

- ↑ Wilson JG, Roth CB, Warkany J. An analysis of the syndrome of malformations induced by maternal vitamin a deficiency. Effects of restoration of vitamin a at various times during gestation. Am J Anatomy. 1953;92(2):189–217.

- ↑ Friedman, N. J., & Kaiser, P. K. Essentials of ophthalmology. Elsevier Health Sciences (2007).

- ↑ Jump up to: 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Onwochei, B. C., Simon, J. W., Bateman, J. B., Couture, K. C. & Mir, E. Ocular colobomata. Surv. Ophthalmol. 45, 175–194 (2000).

- ↑ Jump up to: 8.0 8.1 8.2 Bavbek, T., Ogüt, M. S. & Kazokoglu, H. Congenital lens coloboma and associated pathologies. Doc. Ophthalmol. Adv. Ophthalmol. 83, 313–322 (1993).

- ↑ Jump up to: 9.0 9.1 Tawfik, H. A., Abdulhafez, M. H., Fouad, Y. A., & Dutton, J. J. Embryologic and fetal development of the human eyelid. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery, 32(6), 407 (2016).

- ↑ Byun, T. H., Kim, J. T., Park, H. W., & Kim, W. K. Timetable for upper eyelid development in staged human embryos and fetuses. The Anatomical Record: Advances in Integrative Anatomy and Evolutionary Biology, 294(5), 789-796 (2011).

- ↑ Meythaler, H. & Koniszewski, G. [Colobomas of the eyelids]. Fortschritte Ophthalmol. Z. Dtsch. Ophthalmol. Ges. 82, 391–392 (1985).

- ↑ Jump up to: 12.0 12.1 Warburg, M. Classification of microphthalmos and coloboma. J. Med. Genet. 30, 664–669 (1993).

- ↑ Jump up to: 13.0 13.1 Stoll, C., Alembik, Y., Dott, B. & Roth, M. P. Epidemiology of congenital eye malformations in 131,760 consecutive births. Ophthalmic Paediatr. Genet. 13, 179–186 (1992).

- ↑ Pagon, R. A. Ocular coloboma. Surv. Ophthalmol. 25, 223–236 (1981).

- ↑ Smith, H. B., Verity, D. H., & Collin, J.R. O. The incidence, embryology, and oculofacial abnormalities associated with eyelid colobomas. Eye, 29(4), 492-498 (2015).

- ↑ Trainor PA, Dixon J, Dixon MJ . Treacher Collins syndrome: etiology, pathogenesis and prevention. Eur J Hum Genet 2009; 17 (3): 275–280.

- ↑ True coloboma of upper eyelid. at <http://one.aao.org/image/true-coloboma-of-upper-eyelid-2>

- ↑ Coloboma of the lens. at <http://one.aao.org/image/coloboma-of-lens-2>

- ↑ Typical iris coloboma, right eye. at <http://one.aao.org/image/typical-iris-coloboma-right-eye-2>

- ↑ Coloboma. at <http://one.aao.org/image/coloboma-5>

- ↑ Optic nerve coloboma, right eye. at <http://one.aao.org/image/optic-nerve-coloboma-right-eye-2>

- ↑ Schubert, H. D. Structureal Organization of Choroidal Colobomas of Young and Adult Patients and Mechanism of Retinal Detachment. Trans. Am. Ophthalmol. Soc. 103, 457–472 (2005).

- ↑ L. L. Seah, C. T. Choo, and K. S. Fong, “Congenital upper lid colobomas: management and visual outcome,” Ophthalmic Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 190–195 (2002).

- ↑ A. K. Grover, Z. Chaudhuri, S. Malik, S. Bageja, and V. Menon,“Congenital eyelid colobomas in 51 patients,” Journal of Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, vol. 46, no. 3, pp. 151–159 (2009).

- ↑ Olsen, T. W. Visual acuity in children with colobomatous defects. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 8, 63–67 (1997).

- ↑ Jump up to: 26.0 26.1 Olsen, T. W., Summers, C. G. & Knobloch, W. H. Predicting visual acuity in children with colobomas involving the optic nerve. J. Pediatr. Ophthalmol. Strabismus 33, 47–51 (1996).

- ↑ Tripathy K, Chawla R, Sharma YR, Venkatesh P, et al. Prophylactic laser photocoagulation of fundal coloboma: does it really help? Acta Ophthalmol. 2016;94(8):e809-e810.