Modified Osteo-Odonto-Keratoprosthesis

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Introduction

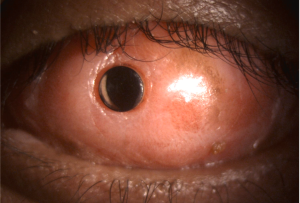

The osteo-odonto-keratoprosthesis (OOKP) is a corneal prosthesis (KPro) with a biological haptic that was designed by Strampelli [1] and later on, modified (MOOKP) by Falcinelli [2]. It is used in patients with bilateral corneal blindness and end-stage ocular surface disease. [3] This complicated and laborious multidisciplinary procedure consists of replacing the ocular surface with a full-thickness oral mucosa graft that provides sustenance to a polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) optical cylinder embedded and supported by the patient’s tooth and alveolar bone. [2] [4]

In 2001-2002, the Rome-Vienna protocol was created to standardize and improve the surgical technique [2], becoming the gold-standard for this procedure nowadays. Although it is indeed a complex surgery, careful patient selection and strict follow-up make MOOKP a reliable option for visual rehabilitation in patients with end-stage ocular surface disease. [3]

Indications

The indications for the MOOKP procedure include cases of bilateral end-stage ocular surface disease that has repeatably failed to or cannot be managed with any other surgical reconstruction method.[2] Severe and destructive autoimmune diseases and chemical injuries can be approached with this procedure, including:

- Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS)

- Toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN)

- Ocular mucous membrane pemphigoid (OMMP)

- Cicatricial trachoma

- Ocular surface burns

- Severe exposure keratopathy

- End-stage autoimmune dry eye disease (e.g. Sjögren’s and graft-versus-host disease).[5] [6]

Contraindications

Absolute

- Pediatric patients due to their undeveloped dental arches and a higher risk of laminae resorption

- Phthisis bulbi

- No light perception

- Retinal detachment

- Unrealistic expectations

Relative

- Defective light perception

- Mentally unstable patients

- Poor compliance or unreliable follow-up

- Maxillofacial deformities

Patient assessment

Ophthalmological assessment

Ophthalmological assessment must include a full history and examination.

- Visual acuity of minimum light perception should be recorded (light perception and projection, entoptic phenomena color differentiation, potential acuity measurement with the PAM device, laser interferometry, fERG. or VEP).

- Ultrabiomicroscopy (UBM)

- B-scan ultrasound

- A-scan biometry

- Intraocular pressure measurement. [2][6]

It is crucial to establish a preoperative diagnosis of glaucoma since this condition is the most common complication causing vision deterioration in patients with MOOKP. [7]

Dental examination

A maxillofacial surgeon should perform the dental examination. It must include a complete buccal mucosa assessment. A mono-radicular tooth is selected, usually a canine. [8][9] Imaging techniques, such as orthopantomography, X-ray, and cone-beam CT modality, can help evaluate and select the appropriate tooth piece. [10][11]

The patient should perform chlorhexidine and nystatin mouthwashes one to two days before surgery and cease smoking beforehand to preserve the tooth´s integrity and the oral mucosa. [2][4][9]

Pre-anesthetic evaluation

Some patients might have associated face, neck, and/or airway lesions that could make endotracheal intubation difficult. Therefore, pre-anesthetic risk evaluation should include the following:

- Mallampati Score

- American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Classification.

In stage 1 and Intermediary stage, nasotracheal intubation is recommended. On the other hand, stage 2 requires orotracheal intubation. [12][13]

Psychological evaluation

The preoperative assessment should also include an extensive psychological evaluation. Patients must be aware of the risks, understand the possible visual and cosmetic outcomes and reasonable expectations of the procedure, and know that life-long follow-up is necessary.

Surgical Technique

Stage 1

Preparation of the anterior and posterior segment

- If there are fibrotic and/or degenerative changes, both the cornea and sclera are laid bare by detaching this tissue from the ocular surface.

- If the cornea is free of fibrotic tissue, a peritomy extended to the canthi is performed.

- A Flieringa scleral fixation ring is sutured in place, and traction threads are used to hook the recti muscles insertions

- A limbal incision is performed to remove the anterior and posterior synechiae, the iris, and the lens

- A cooled balanced saline solution may be used to avoid using diathermy for bleeding control.

- Vitrectomy with high-frequency, moderate aspiration and no infusion is performed.

- The corneal incisions are sutured with Vicryl 7-0 separate stitches

- The anterior chamber is formed with an air bubble

- The Flieringa ring is removed.

- The cornea and sclera are covered with the conjunctiva or with lid suturing

Preparation of the OOAL

The maxillofacial surgeon performs this stage.

It is recommended that the dental lamina measures 15-16mm in length, 8-10 mm in the former labiopalatina dimension, and no less than 3mm thick. The selected monoradicular tooth is osteotomized along with the surrounding alveolar bone and its periosteum. A single stitch on the mucosa edge is done for repair.

- The osteodental block surface is examined, and the one with the largest amount of alveolar bone is chosen.

- Half of the root is removed using a diamond-coated milling cutter, starting from the surface with the least alveolar bone surface.

- The pulp’s canal is opened, and the pulp is removed with the milling cutter. The dentine is polished to achieve the desired thickness.

- A central hole is drilled to allow the insertion of the optical cylinder. [14] [15]

- The optical cylinder is personalized to be as close to emmetropia as possible. [16]

- The cylinder is glued to the drilled hole using acrylic bone cement or universal resin cement. [17]

- The OOAL is inserted subcutaneously in the contralateral orbitozygomatic area.

Intermediary stage

This stage is performed a month after stage 1.

- A 3-4 cm graft from the buccal mucosa is obtained under general anesthesia.

- The submucosal fat is removed, and the graft is placed in a broad spectrum antibiotic solution.

- A conjunctival peritomy is dissected up to the recti muscle insertions.

- The muscles are secured with a 5-0 silk suture

- The corneal epithelium and Bowman’s membrane are removed.

- If there is a perforation or Descemetocele, a lamellar or penetrating keratoplasty is performed.

- The mucosal graft is rinsed out of the antibiotic solution with BSS and laid down on the ocular surface.

- The mucosal graft is sutured in close proximity to the recti muscle insertions.

Stage 2

The second stage is performed three months after the implantation of the buccal mucosa graft.

- The OOAL is retrieved from the orbitozygomatic pocket and examined for signs of resorption or necrosis.

- The mucosal graft is excised superiorly, which creates a flap that remains attached 3mm inferior to the limbus.

- A Flieringa ring is sutured to the sclera, and traction sutures are placed 180º apart.

- Four scleral sutures are placed at 3, 6, 9, and 12 o’clock; these sutures will fixate the OOAL.

- Three corneal sutures are placed at 5, 7, and 12 o’clock; these sutures will help with the insertion of the optical cylinder's posterior end.

- The center of the cornea is marked and trephined

- The OOAL is put in place; the posterior surface of the optical cylinder is placed fitting the area of trephination made to the central cornea.

- The previously set sutures are arranged to fix the implant.

- BSS or air should be used to reform the anterior chamber.

- More sutures are added to fix the implant to the anterior surface firmly and to align the optical cylinder to the fovea correctly.

- The Flieringa ring is removed.

- The mucosal graft flap is closed.

- Finally, the surgeon makes a trephination of the anterior surface of the optical cylinder

Postoperative recommendations

Postoperative recommendations for this procedure include using an antiseptic mouthwash (Chlorhexidine 0.2%) after the intermediary stage, systemic broad-spectrum and topical antibiotics after each stage, and systemic steroids. [18][19] After stage 2, patients are given oral ocular hypotensive drugs (acetazolamide) as needed.[20] A scleral shield is applied, and bed rest in the supine position is recommended until the air is absorbed. Daily hygiene of the prosthesis using BSS is also recommended.

Outcomes

The most common indication for surgery is autoimmune disease, closely followed by chemical injury. [3] MOOKP has shown excellent long-term anatomic and functional success rates. The largest case series included 181 patients and showed a 93.9% anatomic success rate.[4] At 18 years of follow-up, there was an 85% probability of anatomic success (95% CI: 79.3-90.7%). Visual acuity outcomes varied depending on the diagnostic group. It ranged from 0.41 Log Mar in cases of bullous keratopathy secondary to glaucoma surgery to 0.8 Log Mar in cases of corneal burns and dry eye syndrome.

A worldwide analysis of all published MOOKP cases revealed that 78% of all patients achieve a 20/400 or better at the end of their follow-up period, and that 91.2% improved at least temporarily after MOOKP surgery. Mean anatomic success (KPro retention) from this analysis showed an astonishing 88.25% at last follow-up.[3]

Complications

Intraoperative complications

Some of the most frequent intraoperative complications are adjacent root exposure, oral mucosa flap perforation, mouth numbness, mouth tightness, submucosal scar band, paresthesias, and infection at grafting site, mucosal graft defect, overgrowth, or necrosis/melting, and vitreous hemorrhage.

Postoperative complications

Lamina-resorption is one of the most frequent postoperative complications. It can end up in anatomical failure. CT scans are the gold standard for detecting laminar resorption; they should be used along with a clinical examination made by an experienced surgeon. [19] Sterile vitritis is commonly associated with early laminar resorption. [21][22]

Glaucoma is significant morbidity with any keratoprosthesis; therefore, it should be established if the patient has a preoperative diagnosis of glaucoma. There should be a particular emphasis on regularly monitoring the postoperative intraocular pressure, as the development of this disease may affect the final visual outcome of an otherwise successful surgery. [7] It can be treated with oral medication (carbonic anhydrase inhibitors) and surgery (valve implantation, cyclophotocoagulation). [23]

Other sight-threatening complications include choroidal/retinal detachment, retroprosthetic membrane, vitreous hemorrhage, and endophthalmitis.

References

- ↑ Strampelli B (1963) Osteo-odontokeratoprosthesis. Ann Ottalmol Clin Ocul 89:1039–1044

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Hille K, Grabner G, Liu C, Colliardo P, Falcinelli G, Taloni M, Falcinelli G (2005) Standards for modified osteoodontokeratoprosthesis (OOKP) surgery according to Strampelli and Falcinelli: the Rome-Vienna Protocol. Cornea 24:895–908

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Ortiz-Morales G, Loya-Garcia D, Colorado-Zavala MF, Gomez-Elizondo DE, Soifer M, Srinivasan B, Agarwal S, Rodríguez-Garcia A, Perez VL, Amescua G, Iyer G. The evolution of the modified osteo-odonto-keratoprosthesis, its reliability, and long-term visual rehabilitation prognosis: An analytical review. The Ocular Surface. 2022 Mar 18.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Falcinelli G, Falsini B, Taloni M, Colliardo P, Falcinelli G (2005) Modified osteo-odonto-keratoprosthesis for treatment of corneal blindness: long-term anatomical and functional outcomes in 181 cases. Arch Ophthalmol 123:1319–1329

- ↑ Tan DTH, Tay ABG, Theng JTS, Lye K-W, Parthasarathy A, Por Y-M, Chan L-L, Liu C (2008) Keratoprosthesis Surgery for End-Stage Corneal Blindness in Asian Eyes. Ophthalmology 115:503–510.e3

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Amescua G, Perez V (2013) Modified Osteo-Odonto-Keratoprosthesis: MOOKP. In: Ocular Surface Disease: Cornea, Conjunctiva and Tear Film. W.B. Saunders, pp 427–433

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Netland PA, Terada H, Dohlman CH (1998) Glaucoma associated with keratoprosthesis. Ophthalmology 105:751–757

- ↑ Liu C, Paul B, Tandon R, et al (2005) The Osteo-Odonto-Keratoprosthesis (OOKP). Seminars in Ophthalmology 20:113–128

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Tay ABG, Tan DTH, Lye KW, Theng J, Parthasarathy A, Por Y-M (2007) Osteo-odonto-keratoprosthesis surgery: a combined ocular–oral procedure for ocular blindness. International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 36:807–813

- ↑ Monaco B, Colliardo P, D’Ambrosio, G. S (1994) La scelta dell’elemento dentale per l’osteoodonto- cheratoprotesi. La TC dei mascellari con programma Dentascan. Proceedings of the Atti LXXIV Congresso SOI 106–116

- ↑ Berg B-I, Dagassan-Berndt D, Goldblum D, Kunz C (2015) Cone-beam computed tomography for planning and assessing surgical outcomes of osteo-odonto-keratoprosthesis. Cornea 34:482–485

- ↑ Raman S, Singh S, Jagdish V (2019) Anesthesia Considerations in Modified Osteo-odonto-keratoprosthesis. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila) 8:8–11

- ↑ Garg R, Khanna P, Sinha R (2011) Perioperative management of patients for osteo-odonto-kreatoprosthesis under general anaesthesia: A retrospective study. Indian Journal of Anaesthesia 55:271

- ↑ Aguilar M, Sawatari Y, Gonzalez A, Lee W, Rowaan C, Sathiah D, Miller D, Perez V, Alfonso E, Parel J-M (2013) IMPROVEMENTS IN THE MODIFIED OSTEO-ODONTO KERATOPROSTHESIS (MOOKP) SURGERY TECHNIQUE. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 54:3481–3481

- ↑ Berg B-I, Peyer M, Kuske L, et al (2019) Comparison of an Er: YAG laser osteotome versus a conventional drill for the use in osteo- odonto-keratoprosthesis (OOKP). Lasers Surg Med 51:531–537

- ↑ Hull CC, Liu CSC, Sciscio A, Eleftheriadis H, Herold J (2000) Optical cylinder designs to increase the field of vision in the osteo-odonto-keratoprosthesis. Graefe’s Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology 238:1002–1008

- ↑ Weisshuhn K, Berg I, Tinner D, Kunz C, Bornstein MM, Steineck M, Hille K, Goldblum D (2014) Osteo-odonto-keratoprosthesis (OOKP) and the testing of three different adhesives for bonding bovine teeth with optical poly-(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) cylinder. Br J Ophthalmol 98:980–983

- ↑ Basu S, Pillai VS, Sangwan VS. Mucosal complications of modified osteo-odonto keratoprosthesis in chronic Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 2013;156:867–73.e2.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Avadhanam VS, Smith J, Poostchi A, Chervenkoff J, Al Raqqad N, Francis I, Liu CS (2019) Detection of laminar resorption in osteo-odonto-keratoprostheses. Ocul Surf 17:78–82

- ↑ Iyer G, Srinivasan B, Agarwal S, Shetty R, Krishnamoorthy S, Balekudaru S, et al. Glaucoma in modified osteo-odonto-keratoprosthesis eyes: role of additional stage 1A and Ahmed glaucoma drainage device-technique and timing. Am J Ophthalmol 2015;159:482–9.e2.

- ↑ Yu J, Huang Y, Song J, Wang L, Wang F (2011) Keratoprosthesis sterile vitritis. Ophthalmology 118:221

- ↑ Grassi CM, Crnej A, Paschalis EI, Colby KA, Dohlman CH, Chodosh J (2015) Idiopathic vitritis in the setting of Boston keratoprosthesis. Cornea 34:165–170

- ↑ Kumar RS, Tan DTH, Por Y-M, Oen FT, Hoh S-T, Parthasarathy A, Aung T (2009) Glaucoma Management in Patients With Osteo-odonto-keratoprosthesis (OOKP). Journal of Glaucoma 18:354–360