Malarial Retinopathy

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Malaria is a common cause of death in certain tropical countries, with sub-Saharan African children under 5 years old representing the vast majority of fatalities each year.[1] Cerebral malaria, defined as an unarousable coma in a malaria-infected patient with no apparent alternative explanation for altered mental status, is a severe and often fatal complication of malaria. Patients with cerebral malaria or other forms of severe malarial infection commonly develop a classic pattern of retinal changes first described in Malawian children in 1993.[2]

Pathophysiology

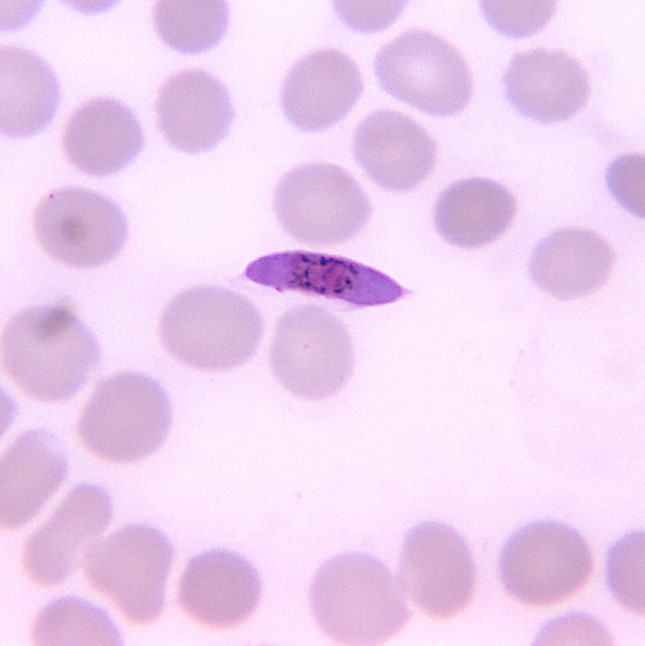

The pathogenesis of malarial retinopathy is associated with that of cerebral malaria, i.e. sequestration of infected red blood cells in retinal and cerebral microvasculature, causing vessel obstruction and reduced blood flow resulting in downstream ischemia and hypoxia.[3] Dysregulation of the angiopoietin-Tie-2 pathway, an important regulator of endothelial cell function and vessel integrity, has been linked with both retinopathy and mortality in pediatric cerebral malaria.[4] New research is showing that increased expression of group A Plasmodium Falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 (PfEMP1) on host erythrocytes due to the parasite is correlated with increased severity of cerebral malaria. [5] [6] Additionally, serum levels of histidine-rich protein 2 (HRP2), a malaria parasite protein currently of unknown significance, can be elevated in patients with malarial retinopathy. [7] [8] Cerebral malaria and malarial retinopathy are most commonly seen in severe infections by Plasmodium falciparum, though patients infected with Plasmodium vivax have also been noted to have some features of malarial retinopathy.[9] A recent study developed a retinal model in mice to further study cerebral malaria – specifically, they found that malaria parasites cross the blood-retinal barrier and infiltrate the neuroretina potentially through Müller glial cells.[10]

Diagnosis

Signs

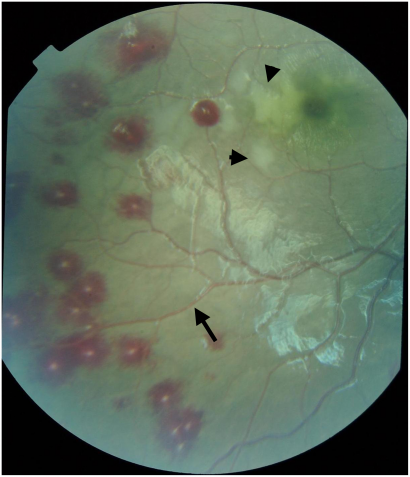

The characteristic changes of malarial retinopathy consist of retinal whitening, vessel discoloration, retinal hemorrhages, and optic disc edema. Fundus findings are typically symmetrical between the two eyes.[2]

Retinal whitening

Retinal whitening may be seen in the macula (sparing the foveola), though some patients may only develop retinal whitening in the periphery. Hence, indirect ophthalmoscopy through a dilated pupil is important for establishing the diagnosis. While some patients with malaria have been noted to have cotton-wool spots, the whitening typical of malarial retinopathy tends to be less vivid, more widely distributed, and may be poorly demarcated.[3] Fluorescein angiography studies have demonstrated that this whitening corresponds to retinal non-perfusion.[11] Patients with cerebral malaria commonly develop thrombi composed of fibrin and platelets, and it is thought that thrombosis of retinal microvasculature induces ischemia and subsequent hypoxia, leading to intra-cellular edema and loss of retinal transparency.[12]

Vessel discoloration

Retinal vessels may be noted to be orange or white, particularly in the retinal periphery; and tramlining may be seen in larger vessels. Discoloration may be noted in discrete sections of vessels or in a branching pattern.[3] To date, this finding has only been described in the pediatric population.[13] The discoloration is likely related to drastically reduced hemoglobin levels in parasitized red blood cells that tend to sequester in retinal capillaries and in branch points of the peripheral retinal vasculature.[14]

Retinal hemorrhages

Intra-retinal hemorrhages, often with a white center and resembling Roth spots, are a common finding in patients infected with malaria. While patients with asymptomatic or mild infections may have no or few hemorrhages, patients with severe malaria may manifest hemorrhages that are too numerous to count. Hemorrhages may sometimes involve all retinal layers, and can also extend into both the pre-retinal and sub-retinal spaces.[12] Interestingly, the number of retinal hemorrhages has been positively correlated with cerebral hemorrhages at postmortem examination. [15]

Optic disc edema

Optic disc edema can be seen in various etiologies of coma, including cerebral malaria. While this sign is not specific to malarial retinopathy, its presence in patients with cerebral malaria is a particularly poor prognostic sign.[3] However, clinically defined cerebral malaria that only has papilledema on fundoscopic exam might be a sign of severe illness and may be secondary to a co-existing infection or pathology. [16]

Additional clinical signs in cerebral malaria

Patients are sometimes noted to have nystagmus, wandering eye movements, and cystoid macular edema.[12][17]

Optical Coherence Tomography

OCT can provide significant information to confirm the diagnosis of MR, though access to Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) in regions where malaria is endemic can be limited. One study found that 90-93% of eyes affected by malarial retinopathy had findings of ‘hyper-reflective capillaries or vessels’ on OCT, which the authors postulate to represent endothelial sequestration of pRBCs, specifically due to hemozoin, a metabolic by-product of the falciparum parasite.[18] Additionally, this hyper-reflectivity disappears within 48 hours of starting treatment in all patients.

Diagnostic significance

Diagnosing coma caused by cerebral malaria versus other causes of encephalopathy is a challenge in resource-poor areas, and misdiagnosis can have life-threatening consequences[19]. For example, a prospective autopsy study in Malawi found that 23% of children who died with the diagnosis of cerebral malaria actually did not have the histopathological hallmarks of cerebral malaria, but had other causes of death[20]. Misdiagnosis occurs because the clinical manifestations of severe malaria in children (coma, seizures, hypertonia, hyperventilation, and anemia) are not specific to malaria. When children present with these symptoms, along with malaria parasites in the peripheral blood, a presumptive diagnosis of cerebral malaria is often made, yet the parasitemia may be an incidental finding in endemic regions. In much of these same regions, laboratory and radiographic investigations to narrow the differential are typically not available.

The unique retinal findings in cerebral malaria correlate to the histopathology and severity of the disease[21][14]. These are the most specific and sensitive signs of cerebral malaria that are available[20]. One study showed that the detection of malarial retinopathy in comatose children with malarial parasitemia had a positive predictive value of 95% and a negative predictive value of 90% for the diagnosis of cerebral malaria, compared to a positive predictive value of only 77% in patients diagnosed clinically, using World Health Organization criteria, without a dilated funduscopic exam[20][22]. Current research focuses on the utility of non-ophthalmologists to directly examine and/or capture retinal images for automated and expert review[23][22].[24] New research is also working to determine serum biomarkers since even access to indirect ophthalmoscopes in these settings can be scarce. Specifically, circulating levels of endothelial activation markers such as ICAM-1, vWF, Ang-2 and sTie-2 have been associated with malarial retinopathy. [25] As mentioned before, access and education around these new developments, as well as to equipment, supplies, and training, remain a challenge.

Differential diagnosis

- Commotio retinae

- Purtscher retinopathy and Purtscher-like retinopathy

- Retinal vein occlusion

- Shaken baby syndrome

Though trauma may be associated with retinal whitening, hemorrhages, and optic disc edema, trauma is not known to cause white or orange discoloration of retinal vasculature.

Management

Medical therapy

Treatment requires systemic anti-malarial therapy guided by local anti-malarial sensitivity and resistance patterns. No treatment for the retinopathy itself has been described thus far.

Prognosis

The majority of children with cerebral malaria regain consciousness within 48 hours without permanent neurological sequalae, while approximately 10% will develop lasting neurological deficits and about 20% will die from the illness.[26] One study found that children with retinopathy-positive cerebral malaria (RP CM) were more likely to have deficits in language development than those with retinopathy-negative cerebral malaria (RN CM). [27] The Blantyre Malaria Project Epilepsy Study found that RP CM is a risk factor for adverse neurologic outcomes like epilepsy, disruptive behavioral disorders, and other neurodisabilities. [28] The severity of malarial retinopathy in these children is correlated with longevity of coma and increased risk of death, with the presence of optic disc edema and peripheral retinal whitening conferring the highest relative risk.[2][21] Studies in adults infected with Plasmodium falciparum found that mild retinopathy may be present in adults with uncomplicated malaria, but that more severe malarial retinopathy was associated with more severe systemic disease.[13] More specifically, one study found that children with RP CM malaria is associated with significantly higher serum CRP, erythropoietin, and ferritin and higher CSF Erythropoietin, EPO, and plasma:albumin ratio when compared to children with RN CM, potentially indicating that a positive finding of retinopathy correlates with more serious systemic disease that presents later. [29]

Visual Outcomes

In pediatric survivors of severe malaria, retinopathy resolves within 1-4 weeks.[21] While some patients may develop cortical blindness as a neurological complication of severe malaria, children who survive severe malaria have not been found to have long-term visual deficits attributable to their retinal changes.[30] No published data are available regarding long-term visual outcomes in adults.

References

- ↑ World Health Organization. World Malaria Report 2019. https://www.who.int/publications-detail/world-malaria-report-2019. Published December 4, 2019. Accessed April 4, 2019.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Lewallen S, Taylor TE, Molyneux ME, Wills BA, Courtright P. Ocular fundus findings in Malawian children with cerebral malaria. Ophthalmology. 1993;100(6):857-861.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Beare NAV, Taylor TE, Harding SP, Lewallen S, Molyneux ME. Malarial retinopathy: a newly established diagnostic sign in severe malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;75(5):790-797.

- ↑ Conroy AL, Glover SJ, Hawkes M, et al. Angiopoietin-2 levels are associated with retinopathy and predict mortality in Malawian children with cerebral malaria: a retrospective case-control study. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(3):952-959.

- ↑ Shabani, E., Hanisch, B., Opoka, R.O., Lavstsen, T. & John, C.C. Plasmodium falciparum EPCR-binding PfEMP1 expression increases with malaria disease severity and is elevated in retinopathy negative cerebral malaria. BMC medicine 15, 1-14 (2017).

- ↑ Abdi, A.I., et al. Differential Plasmodium falciparum surface antigen expression among children with Malarial Retinopathy. Scientific reports 5, 1-10 (2015).

- ↑ Seydel, Karl B., et al. "Plasma concentrations of parasite histidine-rich protein 2 distinguish between retinopathy-positive and retinopathy-negative cerebral malaria in Malawian children." The Journal of infectious diseases 206.3 (2012): 309-318.

- ↑ Kariuki, Symon M., et al. "Value of Plasmodium falciparum histidine-rich protein 2 level and malaria retinopathy in distinguishing cerebral malaria from other acute encephalopathies in Kenyan children." The Journal of infectious diseases 209.4 (2014): 600-609.

- ↑ Kochar A, Kalra P, SB V, et al. Retinopathy of vivax malaria in adults and its relation with severity parameters. Pathog Glob Health. 2016. 110(4/5):185-193.

- ↑ Paquet-Durand, François, et al. "A retinal model of cerebral malaria." Scientific reports 9.1 (2019): 1-15.

- ↑ Glover SJ, Maude RJ, Taylor TE, Molyneux ME, Beare NAV. Malarial retinopathy and fluorescin angiography findings in a Malawian child with cerebral malaria. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10:440.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 White VA, Lewallen S, Beare NAV, Molyneux ME, Taylor TE. Retinal pathology of pediatric cerebral malaria in Malawi. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(1):e4317.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Maude RJ, Beare NAV, Abu Sayeed A, et al. The spectrum of retinopathy in adults with Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2009;103(7):665-671.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Lewallen S, White VA, Whitten RO, et al. Clinical-histopathological correlation of the abnormal retinal vessels in cerebral malaria. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118(7):924-8.

- ↑ White, Valerie A., et al. "Correlation of retinal haemorrhages with brain haemorrhages in children dying of cerebral malaria in Malawi." Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 95.6 (2001): 618-621.

- ↑ Lewallen, Susan, et al. "Using malarial retinopathy to improve the classification of children with cerebral malaria." Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 102.11 (2008): 1089-1094.

- ↑ MacCormick IJC, Maude RJ, Beare NAV, et al. Grading fluorescein angiograms in malarial retinopathy. Malar J. 2015;14:367.

- ↑ Tu, Zhanhan, et al. "Cerebral malaria: insight into pathology from optical coherence tomography." Scientific Reports 11.1 (2021): 1-12.

- ↑ Makani J, Matuja W, Liyombo E, Snow RW, Marsh K, Warrell DA. Admission diagnosis of cerebral malaria in adults in an endemic area of Tanzania: implications and clinical description. QJM. 2003 May;96(5):355-62.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Taylor TE, Fu WJ, Carr RA, et al. Differentiating the pathologies of cerebral malaria by postmortem parasite counts. Nat Med. 2004;10(2):143-145.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Beare NA, Southern C, Chalira C, Taylor TE, Molyneux ME, Harding SP. Prognostic significance and course of retinopathy in children with severe malaria. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122(8):1141-7.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Beare NA, Lewallen S, Taylor TE, Molyneux ME. Redefining cerebral malaria by including malaria retinopathy. Future Microbiol. 2011 Mar;6(3):349-55.

- ↑ Joshi V, Agurto C, Barriga S, et al. Automated detection of malarial retinopathy in digital fundus images for improved diagnosis in Malawian children with clinically defined cerebral malaria. Sci Rep. 2017;7:42703.

- ↑ Wilson KJ, Dhalla A, Meng Y, Tu Z, Zheng Y, Mhango P, Seydel KB, Beare NAV. Retinal imaging technologies in cerebral malaria: a systematic review. Malar J. 2023 Apr 26;22(1):139.

- ↑ Conroy, Andrea L., et al. "Endothelium-based biomarkers are associated with cerebral malaria in Malawian children: a retrospective case-control study." PloS one 5.12 (2010): e15291

- ↑ Idro R, Jenkins NE, Newton CR. Pathogenesis, clinical features, and neurological outcome of cerebral malaria. Lancet Neur. 2005;4(12):827-840.

- ↑ Boivin, Michael J., et al. "Developmental outcomes in Malawian children with retinopathy‐positive cerebral malaria." Tropical Medicine & International Health 16.3 (2011): 263-271.

- ↑ Birbeck, Gretchen L., et al. "Blantyre Malaria Project Epilepsy Study (BMPES) of neurological outcomes in retinopathy-positive paediatric cerebral malaria survivors: a prospective cohort study." The Lancet Neurology 9.12 (2010): 1173-1181.

- ↑ Villaverde, Chandler, et al. "Retinopathy-positive cerebral malaria is associated with greater inflammation, blood-brain barrier breakdown, and neuronal damage than retinopathy-negative cerebral malaria." Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society 9.5 (2020): 580-586.

- ↑ Beare NAV, Southern C, Kayira K, Taylor TE, Harding SP. Visual outcomes in children in Malawi following retinopathy of severe malaria. Br J Ophthalmol. 2004;88(3):321-324.