Shaken Baby Syndrome

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Shaken Baby Syndrome or Non Accidental Trauma

Overview:

Child abuse is a significant social problem which is associated with a high morbidity and mortality. “Shaken Baby Syndrome” (SBS) is one form of physical child abuse, a non-accidental traumatic (NAT) brain injury. It is included in abusive head trauma classification.[1] In 6% of reported cases of child abuse, an ophthalmologist is responsible for initially recognizing the abuse.[2] Shaken Baby Syndrome (SBS) affects an estimated 1400 children/year in the United States[3] and it is thought an astounding 2 million children are abused each year in the US alone. Retinal findings may be the only manifestation of this abuse. It is a diagnosis that has important medical-legal implications and one that cannot be overlooked as a child’s safety may very well be at stake.

Detailed Description:

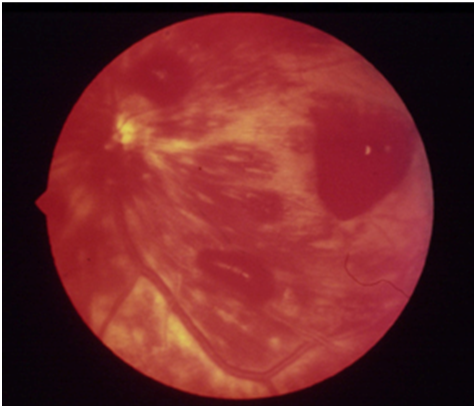

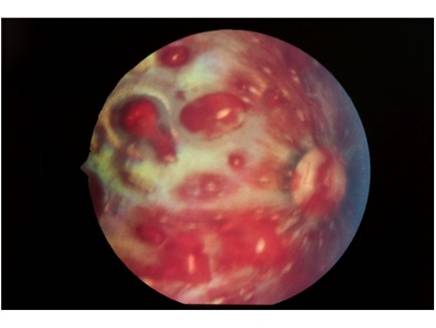

The ocular manifestations of child abuse are numerous. There may be signs of periorbital trauma (i.e. ecchymosis, lid edema, orbital fractures), anterior segment trauma (i.e. hyphema, iris prolapse, corneal laceration, cataract), or posterior segment trauma (i.e. vitreous hemorrhage, retinal detachment, optic nerve avulsion).[4] There may be associated brain injury resulting in nystagmus, cortical blindness, encephalopathy, or cranial nerve palsies - most commonly subdural hemorrhage. Retinal hemorrhages are the cardinal manifestation of SBS. The incidence of retinal hemorrhages in SBS is approximately 85%.[5] A prospective case series at Lille University in France found that 27% of children with confirmed intentional head injury (NAT to the head) had mild or moderate retinal hemorrhages, and 57% had severe hemorrhages.[6] Classically, children with SBS have retinal hemorrhages which are multilayered – preretinal, intraretinal, and subretinal. They are usually too numerous to count and extend out to the retinal periphery (i.e. not just confined to the posterior pole). Macular retinoschisis (splitting of the retinal layers) may also be associated with SBS.[7] As retinal hemorrhages may subside over time, prompt retinal photography is recommended at the time of discovery of retinal hemorrhages on dilated funduscopic exam for medical-legal purposes and to serve as a baseline for future comparison. If possible, extended ophthalmoscopy with examination of the entire retina using scleral depression is recommended to also evaluate for peripheral nonperfusion (from retinal vascular disruptions) and neovascularization as well as for peripheral retinal tears, hemorrhages, and other pathology. If possible, wide sweeping photographs and fluorescein angiography are recommended as soon as the discovery of retinal hemorrhages from SBS / NAT are discovered. Examination under anesthesia may be required to obtain imaging and administer treatment if needed.

Epidemiology/Risk Factors:

Perhaps the greatest diagnostic clue is a detailed history that is incompatible with the extent and severity of the injuries found on dilated fundus exam. Suspected abusers may confess to investigators in up to 47% of cases[8]. A child with classic evidence supporting physical abuse (i.e. old fractures, bruises of varying ages, signs of neglect, new sleep or behavioral issues, unexplained mental status changes) should alert the clinician to request a dilated fundus exam looking for SBS. Subdural hemorrhage, occipital lobe insult, and Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) <15 are important risk factors for retinal hemorrhages.[9] Not all patients will have obvious non-ocular findings, however, and clinicians should maintain a low threshold for dilated fundus examination. In a retrospective review of 30 SHS patients at Vanderbilt, only 47% had bruises and only 13% had long bone fractures.[10] Corroborating this finding, a review of 557 patients diagnosed with NAT at SUNY Syracuse revealed no significant associations between retinal hemorrhage and visible injuries to the head or face, cutaneous trauma, or non-skull-bone fractures. Additionally, patients with retinal hemorrhages do not always have head imaging indicative of NAT, and normal imaging does not preclude the need for a dilated fundus exam.[11] Children between 3 and 8 months old are at greatest risk of abusive head trauma, and age <2 years is a risk factor for retinal hemorrhages; however, a dilated fundus exam should be performed in children of any age with history or exam findings concerning for child abuse.[9][12] Going forward, machine learning algorithms may be able to assist with identification of at-risk patients based on demographic information and contents of free-text clinical notes.[13]

Etiology/Pathophysiology:

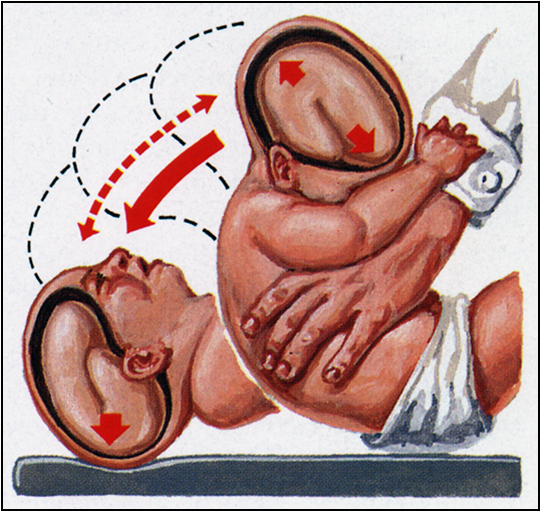

Several mechanisms for the retinal hemorrhages in SBS have been postulated and recently been the subject of some debate (mostly in the courts). The actual cause of retinal hemorrhages is still being studied experimentally. One likely hypothesis implicates repetitive acceleration-deceleration forces which cause damage via vitreoretinal traction.[14] Other possible mechanisms include blunt head impact, increased intracranial pressure, increased intrathoracic pressure, hypoxia, sodium imbalance, or coagulopathies. Vascular disruption may also lead to peripheral nonperfusion which subsequently may result in neovascularization, vitreous hemorrhage, and tractional or combined tractional / rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. Physical eye models[15][16] and computer simulations[17] are being used to understand better the causes of pathology seen in NAT.

Histopathology:

Pathology may reveal findings detailed above (e.g. retinal hemorrhages at multiple levels, nerve avulsion). Perimacular folds and hemorrhagic macular retinoschisis may be found on histopathologic exam and may not be well appreciated on dilated fundus exam if the view is obstructed by vitreous hemorrhage.

Differential Diagnosis:

- Accidental Head Trauma

- Purtscher’s Retinopathy: associated with blunt thoracic trauma

- Terson Syndrome: intraocular hemorrhage associated with intracranial hemorrhage

- Normal Birth

- Valsalva Retinopathy

- Anemia

- Blunt Ocular Trauma

- Coagulopathy

- Forceps Injury

Management/Treatment:

Overall, prevention is the best therapy. Many hospitals and healthcare centers offer classes and education on how to cope with the stresses of parenthood. Ophthalmic exam findings that suggest SBS necessitate urgent, comprehensive evaluation in the emergency department to reduce morbidity and mortality. Nonreactive pupils indicate a substantial risk of mortality. For these patients, ventilatory support and neurosurgical consultation should be pursued immediately. Retinal Hemorrhages and orbital fractures are associated with higher mortality, and the presence of these findings should be communicated clearly with all providers involved in the patient's care.[18] Child protective services and local law enforcement should immediately be alerted in all cases of abuse or suspected abuse. Careful physician documentation is essential for both medical and legal follow up. The American Academy of Pediatrics provides suggested terminology for describing retinal hemorrhages including “nonspecific” (with a differential diagnosis provided), “suggestive,” or “highly suggestive” of abusive head trauma.[19]

For all patients with retinal hemorrhages found on dilated fundus exam, retina photographs should be obtained to augment written exam findings. Additionally, wide sweeping fluorescein angiography should be completed to evaluate for peripheral nonperfusion and possible neovascularization development.[20] Peripheral nonperfusion may lead to development of neovascular tissue that subsequently may contribute to vitreous hemorrhage and tractional or complex tractional / rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. If significant peripheral nonperfusion is detected, peripheral scatter laser to all regions of nonperfusion may be considered to reduce the risk of neovascularization and subsequent retinal detachment.

If preretinal blood obscures the macula raising concern for amblyopia, several options can be tried. One option is maintaining the infant upright during the day if possible given other comorbidities.[21] Upright positioning allows the blood to settle inferiorly within the bleb and may allow the fovea to be sufficiently clear to avoid surgical evacuation. Surgical vitrectomy may be needed for nonclearing vitreous hemorrhage, macular hole, or retinal detachment, but procedures are complex in infant eyes and often require consultation with a pediatric retina trained surgeon. Some children will require treatment for amblyopia or strabismus. Patching therapy and glasses may be needed to treat the amblyopia induced by the ocular trauma.

Prognosis:

Prognosis is generally poor; however, it can vary significantly depending on the severity of the trauma and effect on the central neural system. Pupillary nonreactivity on initial exam is associated with substantially increased risk of mortality.[10] Cortical blindness occurs in up to 15%. Victims suffer from high incidences of behavioral, social, motor, and visual problems.

References:

- ↑ Caputo G. and Wu Wei-Chi. Hartnett, ME Editor-in-Chief. Wolters Kluwer Philadelphia PA 2021

- ↑ Ocular manifestations of physical child abuse. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol 1971; 75: 318-332.

- ↑ Newton AW, Vandeven AM. Update on child maltreatment with a special focus on shaken baby syndrome. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2005; 17: 246-251. doi:10.1097/01.mop.0000158730.56669.b1

- ↑ Sternberg P Jr. Trauma: principles and techniques of treatment. In: Ryan SJ, ed. Retina, 2ndedn, vol. 3. St. Louis: Mosby; 1994: 2351-2378.

- ↑ Kivlin JD, Simons KB, Lazoritz S, Ruttum MS. Shaken baby syndrome. Ophthalmology. 2000;107(7):1246-1254. doi:10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00161-5

- ↑ Vinchon M, de Foort-Dhellemmes S, Desurmont M, Delestret I. Confessed abuse versus witnessed accidents in infants: comparison of clinical, radiological, and ophthalmological data in corroborated cases. Childs Nerv Syst. 2010;26(5):637-645. doi:10.1007/s00381-009-1048-7

- ↑ Greenwald, Weiss, Oestrerle, Friendly. Traumatic retinoschisis in battered babies. Ophthalmology. 1986; 93(5): 618-625

- ↑ Jenny, Hymel, Ritzen, et al. Analysis of missed cases of abusive head trauma. JAMA 1999; 281: 621-626.

- ↑ Jump up to: 9.0 9.1 Giannakakos VP, Dosakayala N, Huang D, Yazdanyar A. Predictive value of non-ocular findings for retinal haemorrhage in children evaluated for non-accidental trauma. Acta Ophthalmol. 2022;100(3):312-321. doi:10.1111/aos.14936

- ↑ Jump up to: 10.0 10.1 McCabe CF, Donahue SP. Prognostic indicators for vision and mortality in shaken baby syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118(3):373-377. doi:10.1001/archopht.118.3.373

- ↑ Simon CL, Ude I, Levin MR, Alexander JL. Retinal hemorrhages in abusive head trauma with atraumatic neuroimaging. J AAPOS. 2023;27(1):39-42. doi:10.1016/j.jaapos.2022.10.005

- ↑ Joyce T, Gossman W, Huecker MR. Pediatric Abusive Head Trauma. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; May 22, 2023.

- ↑ Jadhav P, Sears T, Floan G, et al. Application of a Machine Learning Algorithm in Prediction of Abusive Head Trauma in Children. J Pediatr Surg. 2024;59(1):80-85. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2023.09.027

- ↑ Levin AV. Retinal hemorrhage in abusive head trauma. Pediatrics. 2010;126(5):961-970. doi:10.1542/peds.2010-1220

- ↑ Yamazaki J, Yoshida M, Mizunuma H. Experimental analyses of the retinal and subretinal haemorrhages accompanied by shaken baby syndrome/abusive head trauma using a dummy doll. Injury. 2014;45(8):1196-1206. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2014.04.014

- ↑ Song HH, Thoreson WB, Dong P, Shokrollahi Y, Gu L, Suh DW. Exploring the Vitreoretinal Interface: A Key Instigator of Unique Retinal Hemorrhage Patterns in Pediatric Head Trauma. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2022 Jun;36(3):253-263. doi: 10.3341/kjo.2021.0133. Epub 2022 May 6. PMID: 35527527; PMCID: PMC9194735.

- ↑ Suh DW, Song HH, Mozafari H, Thoreson WB. Determining the Tractional Forces on Vitreoretinal Interface Using a Computer Simulation Model in Abusive Head Trauma. Am J Ophthalmol. 2021;223:396-404. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2020.06.020

- ↑ Shah YS, Iftikhar M, Justin GA, Canner JK, Woreta FA. A National Analysis of Ophthalmic Features and Mortality in Abusive Head Trauma. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2022;140(3):227-234. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2021.5907

- ↑ Christian CW, Levin AV; COUNCIL ON CHILD ABUSE AND NEGLECT; The Eye Examination in the Evaluation of Child Abuse. Pediatrics. 2018;142(2):e20181411. doi:10.1542/peds.2018-1411

- ↑ Goldenberg DT, Wu D, Capone A Jr, Drenser KA, Trese MT. Nonaccidental trauma and peripheral retinal nonperfusion. Ophthalmology. 2010;117(3):561-566. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.08.013

- ↑ Uner OE, Stelton CR, Hubbard GB 3rd, Rao P. Visual and Anatomic Outcomes of Premacular Hemorrhage in Non-Accidental Trauma Infants Managed With Observation or Vitrectomy. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2020;51(12):715-722. doi: 10.3928/23258160-20201202-06.PMID: 33339053