Invasive Fungal Infections of the Orbit and Sinuses

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Original authors: Nandigam L, Jaber J, Yazdian A, Onyeka R, Mudie LI, Yen MT

Disease Entity

Background

Invasive fungal infections have increased in incidence with the growth of immunosuppressive therapies in combination with improved diagnostic imaging. Complications of invasive fungal infections are primarily the result of thrombosis and necrosis induced by hyphae invading into local tissue structures1. Orbital infections are the most common complication of invasive fungal infections2,3. Some common ocular complications include preseptal cellulitis, orbital cellulitis, subperiosteal abscesses, and orbital abscesses.

Preseptal cellulitis is infection and inflammation of the periorbital tissues anterior to the orbital septum. Orbital cellulitis is inflammation of the orbital soft tissues and muscles posterior to the orbital septum and within the bony orbit 4,5. It does not involve the globe itself. Subperiosteal abscesses entail the collection of pus in the space between the bones of the orbit and perorbita5. Orbital abscesses are areas of purulence build-up within orbital tissues. Orbital cellulitis affects all age groups but occurs more frequently in children and the immunocompromised.

Orbital complications of infections left untreated can have vision-threatening and even life-threatening consequences5. The purpose of this eye-wiki is to describe orbital complications of fungal sinusitis (OCS), especially focusing on causes other than the well-described Mucormycosis and Aspergillosis. As new chemotherapy and immunotherapy has emerged, new fungal pathogens have also emerged as the cause of invasive fungal sinusitis (IFS).

Etiology

The most common and well-documented causes of IFS are due to infection by the species Mucormycosis and Aspergillus. The overall mortality of mucormycosis is over 54% and nearly 100% for those with disseminated disease or prolonged neutropenia6,7. Yet, there is a growing number of literature documenting infection from other species, including Fusarium proliferatum and F. annulatum, Lomentospora, and Scedosporium species8, Scedosporium/Lomentospora9, and Exserohilum rostratum10. This is significant, as some of these species are intrinsically resistant to first line therapies for IFS.

Invasive versus Non-Invasive

The two main types of fungal sinusitis can be differentiated as non-invasive or invasive, and these classifications are often based on the immunocompetence of the affected patient.

Non-invasive fungal sinusitis is limited to the nasal cavity and sinuses and commonly occurs in immunocompetent individuals. Non-invasive fungal sinusitis has been organized into three subtypes based on the varied histopathology: fungal ball, saprophytic, and allergic fungal rhinosinusitis11. The latter has been documented with the causative genus Exserohilum, a group of 35 species of saprophytic fungus. These species thrive in warmer climates and have been increasingly prevalent in the southern United States over the last 30 years12.

IFS tends to be more prevalent in immunodeficient hosts and invades from the nose and sinuses into the surrounding architecture. The three types of IFS are discussed briefly below11.

Variations of Invasive Fungal Sinusitis

- Acute IFS: Most commonly caused by Mucorales and Aspergillus fumigatus, this variation mainly affects immunocompromised individuals. The disease is characterized by deep tissue infection leading to tissue death and inflammation, presenting with symptoms such as persistent sinusitis, nasal polyps, and sinus calcifications on CT scans. Treatment involves surgical intervention and corticosteroids, although recurrence is common.

- Chronic IFS: Most commonly caused by Aspergillus fumigatus, this infection slowly progresses over 12 weeks. It typically affects middle-aged and immunocompetent adults from Sudan, Saudi Arabia, and India. Symptoms include a mass with proptosis14, unilateral rhinosinusitis with nasal obstruction, and a distinct discharge. The disease is marked by fungal clusters forming a mass and causing a chronic inflammatory reaction. Treatment focuses on repeated surgical cleaning and sinus ventilation, with a generally positive prognosis.

- Granulomatous IFS: Caused by Aspergillus flavus, this disease is chronic and can spread to the orbit and brain. The disease results in severe tissue necrosis and inflammation, leading to symptoms like fever, cough, and headaches. Hyphae accumulate in a dense area similar to mycetoma, a chronic suppurative skin and soft tissue infection, with sparse inflammatory infiltrate. Treatment requires extensive surgical debridement and antifungal therapy, with prognosis varying based on the infection's spread, especially poor when involving the cranium.

- Intermediate IFS15: Documented cases have been caused by Aspergillus fumigatus, Rhizopus sp., and Scedosporium apiospermum. Symptoms last between four and twelve weeks. A review of eight patients with moderate disease progression fell into this category. All patients had orbital, intracranial, or skull base involvement with symptomatic facial pain. The vast majority also reported vision changes. Data on optimal treatment is limited, but most surgeons manage with repeated debridement and antifungal therapy.

Incidence

Orbital complications of sinusitis most commonly affect children under the age of seven, as infections can easily spread through the thin medial wall of the orbit, known as the lamina papyracea, with many blood vessels and nerves containing perforations4. In older individuals, infections of the frontal, maxillary, and sphenoid sinuses are common mechanisms of OCS. The incidence in children is 1.6 per 100,000 and 0.1 per 100,000 in adults. OCS are also more common in males compared to females with a ratio of 2:116.

Risk Factors

Identifying common risk factors is important for prevention and early detection of disease. IFS has several risk factors that often lead to infection, including immunocompromised state, chronic upper respiratory infections, diabetes mellitus, use of corticosteroids, previous nasal surgery, trauma or injury, and environmental exposure. Most commonly, patients with compromised immune systems such as those with HIV/AIDS, leukemia, lymphoma, organ transplant recipients on immunosuppressive therapy, and chemotherapy patients should be monitored for the possibility of contraction of IFS8,10,17,18. Preseptal skin infections and infections of the teeth, ear, or face are significant risk factors and should therefore be adequately treated to prevent spread to the orbit . Interestingly, acute myeloid leukemia patients have been noted to have higher rates of invasive fungal infections as well17. More recently, COVID-19 has also been associated with various bacterial and fungal co-infections and therefore increases the risk of IFS19–21.

Pathophysiology

IFS poses a significant threat as it has the potential to extend beyond the paranasal sinuses, including the maxillary, ethmoid, frontal, and sphenoid sinuses. When predisposing factors weaken the immune system, such as individuals with poorly controlled diabetes or undergoing immunosuppressive therapy, fungal spores can proliferate and penetrate the sinus mucosa22. Once fungal organisms infiltrate the sinus mucosa and cause tissue destruction, they are capable of breaching the delicate barriers separating the sinuses from the orbit and may eventually spread to the brain. This process involves the production of enzymes and toxins by the fungi, facilitating tissue destruction and inflammation. Specifically, fungi like Aspergillus species are known for their ability to produce proteases and mycotoxins that aid in tissue invasion23. This breach allows the fungi to enter the orbit, leading to potential complications such as orbital cellulitis. Invasive sinusitis has the potential to infect as far as the bones, vessels, and nerves, making the symptoms more pronounced. Very rarely can the infection reach the orbit through hematogenous spread. Understanding the intricate pathophysiology of IFS highlights the importance of early recognition and aggressive management to prevent the spread of infection and mitigate potential complications. More detailed pathophysiology, however, is unique to the specific causative species11.

Diagnosis

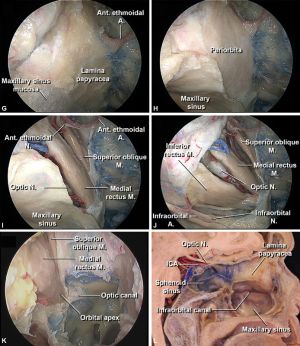

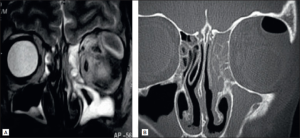

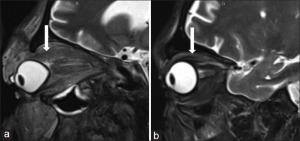

As a brief overview, the extension of sinus infections into the orbit region is characterized by early thickening of the medial rectus, followed by involvement of other extraocular muscles1. Bone erosion of the lamina papyracea and orbital walls, stretching and thickening of the optic nerve, and spread of soft tissue inflammation to the orbital fissures and apex can show worsening of the condition. Cavernous sinus infection would present with altered intensity of the cavernous sinus on MRI. An MRI can also assess for lobar involvement, namely the basifrontal and temporal lobes, and large vessel narrowing.

Classification

For classification of the disease type, the Chandler classification has previously been used to classify orbital complications of sinusitis25. Although this classification is widely utilized, it was created in the 1970s and includes symptoms not associated with orbital infection. Namely, although up to 96% of patients have eyelid swelling, eyelid cellulitis has not been highly associated with acute sinusitis3,4.

Therefore, the Valasco e Cruz classification has been cited numerous times for its more objective classification of orbital complications26. The below table separates orbital complications of cellulitis according to the Valasco classification. Importantly, preseptal cellulitis is not included. This refers to inflammation of tissues localized to the anterior orbital septum. Symptoms include eyelid pain, low-grade fever, normal visual acuity, absence of proptosis, and normal extraocular movements.

| Valasco Classification | Complication | Definition | Symptoms/Signs |

| I | Orbital Cellulitis | Inflammation of tissues posterior to the orbital septum and poor transition zone in the orbital fat. | - Headache

- Orbital pain - Diminished visual acuity - Proptosis - RAPD can be present - Pain on extraocular movement |

| II | Orbital Abscess27 | Collection of heterogeneous fluid within the orbital fat. | - Vision loss to less than 20/200

- Residual proptosis - Residual diplopia - Osteomyelitis - Fever may be present or absent - Presentations can be subacute to chronic |

| III | Subperiosteal Abscess28 | Accumulation of purulence between at least one orbital wall near the sinus and the periorbita | - Eyelid erythema and warmth

- Conjunctival injection - Restricted ocular motility with and without diplopia - Infection affecting the supporting bones of the orbit |

Additional symptoms/signs of ocular involvement in fungal sinusitis include periorbital edema and hyperemia, ophthalmoplegia, ocular pain on movement, and papilledema. Red flag symptoms/signs will be discussed in treatment and include ocular pain on movement, restricted eye movements, photophobia4.

Exam Findings

Systemic signs and symptoms can include fever, chills, erythema, and warmth. Exam findings including decreased visual acuity, proptosis, orbital pain, and diplopia are common. Early detection of relative afferent pupillary defect is vital, as its presence is a predictor of worse post-operative visual outcome29.

Diagnostic Steps

As previously mentioned, orbital symptoms of sinusitis are often due to the progression of untreated or fast-developing invasive sinusitis. In the case of fungal sinusitis, diagnostic steps consider several variables including history, presentation, imaging, endoscopic biopsy with histopathology, and laboratory findings11. Contrast imaging with CT or MRI are the gold standard for diagnostic measures3. One study found that 91% of cases were diagnosed correctly with CT compared to 82% diagnosed clinically4.

However, it is important to note that many new growing abscesses may not have obvious signs on a contrast-CT, with only non-specific signs of inflammation. In the case of orbital abscesses, normal CT scans have been seen to miss the presence of abscess27. Many authors have noted initial orbital biopsies fail to identify the species of fungus, with repeat incisional biopsies necessary to confirm.

Mucorales and Fusobacterium take three to five days to culture 31–33. Aspergillus can take up to twenty-one days34. Exserohilum has been described to take up to 2 weeks to grow12. Lomentospora and Scedosporium species are resistant to many antifungal agents, enforcing the importance of early detection of atypical fungal infections. The diagnosis of these species relies on multiple visualization, isolation, and detection methods through microscopy, culture, and panfungal PCR35.

Additionally, due to the geographic distribution of many fungal entities, a patient’s living, travel, and exposure history can help pinpoint the causing agent or etiology of symptoms while awaiting culture or biopsy results. Granulomatous invasive sinusitis is more common in India, Sudan, and Pakistan. Trauma is associated with mucormycosis in Asian countries and increased immunosuppressants in developed countries account for the majority of cases11.

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnosis for acute presentations can include acute angle-closure glaucoma, cavernous sinus thrombosis, endophthalmitis, epidural abscess, insect bites, meningitis, orbital fracture, and panophthalmitis36.

Additional differential diagnoses for fungal infections include periorbital necrotizing fasciitis, which would have a rapid onset and marked increase in the leukocyte count (mean value compared to 1 in cases of orbital cellulitis with a statistically significant )37.

Further, the diagnosis of primary (direct inoculation) versus secondary (adjacent sinonasal process) infection in immunocompromised individuals requires increased scrutiny on imaging, as secondary infections can resemble acute fulminant IFS due to the infiltration into the facial soft tissues. Early recognition of either disease on imaging is crucial for proper testing and treatment38.

Complications

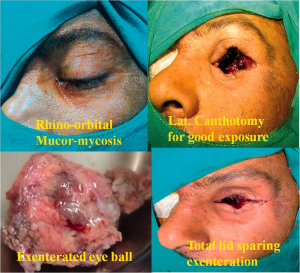

Orbital Compartment Syndrome is an extremely rare complication of orbital cellulitis. The examiner should assess for panophthalmitis, or uveoscleral thickening, and the guitar pick sign, suggestive of tenting of the posterior pole of the globe. Orbital compartment syndrome is an ophthalmic emergency and should be treated with prompt intervention, namely lateral canthotomy and cantholysis33.

Since there are no venous valves in the orbit, infection can spread rapidly via the superior and inferior ophthalmic veins into the venous sinuses of calvarium. This may lead to cavernous sinus thrombosis, intracranial abscesses, and permanent vision loss. This is more likely to occur with late presentations.

Additional complications include frontal sinus fistula, cavernous sinus or orbital apex syndrome, or combined cavernous sinus-orbital apex syndrome are further complications of fungal sinusitis. These complications are associated with headaches, monocular visual loss, or eye pain40,11. Orbital apex syndrome is a result of damage to the superior orbital fissure and optic canal leading to optic nerve dysfunction. It has been described as a complication of sphenoidal aspergillosis 41. Additionally, optic nerve involvement mimicking optic neuritis has been documented along with stroke. When under suspicion of optic nerve involvement, it is important to avoid the use of steroids as it may worsen the fungal infection42.

Management

For orbital involvement of sinusitis, surgery is typically recommended in conjunction with medical management. Medical management will be organized by the previously defined categories of fungal sinusitis.

Medical therapy

Acute IFS: The current standard of care involves systemic antifungal therapy and debridement of ischemic tissue43. A new treatment algorithm has been devised incorporating transcutaneous retrobulbar amphotericin B for IFS. Mortality rates were similar when compared to control using systemic antifungal therapy, and yet there was a significantly lower risk of exenteration. Bilateral functional endoscopic sinus surgery with debridement in conjunction with antifungal therapy decreased the need for revision surgery with no change in outcomes compared to those who underwent repeat sinus surgeries44.

Aspergillus flavus can be treated with itraconazole 8-10 mg per kg per day. The standard medical treatment options for mucormycosis and most other fungal infections are polyenes and azoles45. The polyene Amphotericin B is only available in IV form and has significant side effects such as nephrotoxicity. On the other hand, azoles are administered IV and orally, however, there are notable concerns, such as liver toxicity, drug-drug interactions, and growing resistance. Many cases report prescribing a high initial dose of 100 mg twice daily of amphotericin B followed by long-term treatment with oral azoles such as itraconazole46. One study noted isavuconazole had a better efficacy compared to liposomal amphotericin B18. Although amphotericin B was the standard treatment, studies have found that for progressive disease, the addition of posaconazole may be useful. Posaconazole is a new non-first-line recommendation for mucormycosis with some notable gastrointestinal side effects. However, the efficacy of this drug in vitro and in murine models has mixed data. When the progression of the disease results in necrosis, limited and open surgery should be considered to control the infection.

There are promising new interventions being investigated for their promising results in fungal infections resistant to standard treatments. Otesceonazole is a Cyp51 inhibitor that prevents ergosterol synthesis and is a new target for prophylaxis as well as treatment. Fosmanogepix is a Gwt1 inhibitor, blocking the glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) pathway and preventing the maturation of cell membrane trafficking and anchoring proteins. It has been demonstrated as successful in vitro models of disseminated infection of Candida albicans, C. glabrata, C. auris, C. tropicalis, Coccidioides immitis, and F. solani and pulmonary infection from A. fumigatus, A. flavus, S. prolificans, S. apiospermum and Rhizopus arrhizus6. It is bioavailable both orally and IV and has shown a reduction in tissue fungal burden, with good utility as a predictive biomarker and low recurrence rates. This drug holds high promise to become the front-line therapy for invasive fungal infections.

Fusobacterium can be treated with IV broad-spectrum antibiotics with a range from six days to six weeks, debridement and irrigation32,33. R. ornithinolytica has been described in one published report, and it was treated for 8 weeks in four patients with broad-spectrum antibiotics as well as drainage of abscess and revision sinus surgery47.

Chronic Granulomatous IFS: Medical therapy has been described as necessary14. In cases where patients were treated with surgery alone, all patients developed a recurrence of the disease. Medical therapy recommendations include azoles such as itraconazole and voriconazole for a minimum of three months.

Voriconazole is a long-term treatment for intracranial management as it can cross the blood-brain barrier. It should be given with a loading dose of 6 mg/kg intravenously or oral twice daily for one day before switching to oral tablets at 4 mg/kg/day with documented therapy duration ranging from two to 31 months. A limitation of voriconazole use is the high cost of therapy.

A case of allergic fungal sinusitis was successfully treated with oral corticosteroids and endoscopic sinus surgery, with reversal of the symptoms of bony erosion of the orbit and orbital wall compression48.

Surgery

Surgery is typically necessary for disease that extends into the orbit, especially if red flag symptoms are present and if there is no improvement in the first 48 hours. The Bedwell algorithm for the management of pediatric orbital abscess states that minimal orbital symptoms or an abscess smaller than 10 mm can be managed medically, and otherwise, surgery is recommended30.

Urgent debridement and irrigation of the orbital abscess and sinus are recommended within 24-48 hours as well as the establishment of ventilation to the inflamed sinus. Orbital decompression, orbitotomy, and orbital exenteration can be employed, along with subperiosteal abscess evacuation19. Although exenteration involves removal of the orbit, this still may not guarantee eradication of the apical orbital involvement46. The Lynch incision, an incision to the medial canthus, is historic and still routinely employed in many of the named surgeries as it allows exposure to the orbit. The associated risks for scarring and webbing have popularized the transconjunctival anteromedial microorbitomy approach and transcuruncular approach with their greater potential to avoid visible scars30,49. When fibrosis occurs, antifungal drugs often have poor penetration, and surgery is necessary. Open surgery has vastly been replaced by endoscopic approaches even for complete or near-total excision of the maxillary and ethmoid sinuses. When infection extends intracranially and symptoms of mass effect are present, craniotomy and radical excision may be necessary.

Prognosis

Resolution of symptoms may take two to six months, and the average duration of medical therapy for symptomatic relief is about six to eight months40. Long-term follow-up is necessary for many cases of OCS and the underlying predisposing cause such as poorly controlled diabetes or immunosuppression must be managed to prevent recurrence. Serial CT and MRI may be used to monitor for disease recurrence especially if ongoing immunosuppression is necessary (such as for ongoing treatment of cancer).

References

1. Coutel M, Duprez T, Huart C, Wacheul E, Boschi A. Invasive Fungal Sinusitis with Ophthalmological Complications: Case Series and Review of the Literature. Neuroophthalmology. 45(3):193-204. doi:10.1080/01658107.2020.1779315

2. Hershey BL, Roth TC. Orbital infections. Seminars in Ultrasound, CT and MRI. 1997;18(6):448-459. doi:10.1016/S0887-2171(97)90006-8

3. Anselmo-Lima WT, Soares MR, Fonseca JP, et al. Revisiting the orbital complications of acute rhinosinusitis. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2023;89(5):101316. doi:10.1016/j.bjorl.2023.101316

4. Pelletier J, Koyfman A, Long B. High risk and low prevalence diseases: Orbital cellulitis. Am J Emerg Med. 2023;68:1-9. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2023.02.024

5. Tsirouki T, Dastiridou AI, Ibánez Flores N, et al. Orbital cellulitis. Surv Ophthalmol. 2018;63(4):534-553. doi:10.1016/j.survophthal.2017.12.001

6. Shaw KJ, Ibrahim AS. Fosmanogepix: A Review of the First-in-Class Broad Spectrum Agent for the Treatment of Invasive Fungal Infections. Journal of Fungi. 2020;6(4). doi:10.3390/jof6040239

7. Mucormycosis Statistics | Mucormycosis | Fungal Diseases | CDC. Published June 5, 2020. Accessed March 30, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/mucormycosis/statistics.html

8. Caliskan ZC, Karahan G, Koray N, et al. Invasive fungal rhinosinusitis by Fusarium proliferatum/annulatum in a patient with acute myeloid leukemia: A case report and review of the literature. J Mycol Med. 2024;34(1):101461. doi:10.1016/j.mycmed.2024.101461

9. Lao CK, Ou JH, Fan YC, Wu TS, Sun PL. Clinical manifestations and susceptibility of Scedosporium/Lomentospora infections at a tertiary medical centre in Taiwan from 2014 to 2021: A retrospective cohort study. Mycoses. 2023;66(10):923-935. doi:10.1111/myc.13632

10. Thomas D, Johnson J, Bittar HT, Baluch A. An Uncommon Case of Fungal Rhinosinusitis Caused by the Mold Exserohilum rostratum in a Patient with Relapsed Acute Myeloid Leukemia: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2023;53(6):964-968.

11. Akhondi H, Woldemariam B, Rajasurya V. Fungal Sinusitis. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Accessed March 25, 2024. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK551496/

12. Adler A, Yaniv I, Samra Z, et al. Exserohilum: an emerging human pathogen. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2006;25(4):247-253. doi:10.1007/s10096-006-0093-3

13. Deshazo RD. Syndromes of invasive fungal sinusitis. Medical Mycology. 2009;47(Supplement_1):S309-S314. doi:10.1080/13693780802213399

14. V R, J P, Js M, M T, A I, V R. Chronic Granulomatous Invasive Fungal Sinusitis in Patients With Immunocompetence: A Review. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2023;168(4). doi:10.1177/01945998221097006

15. Burnham AJ, Magliocca KR, Pettitt-Schieber B, et al. Intermediate Invasive Fungal Sinusitis, a Distinct Entity From Acute Fulminant and Chronic Invasive Fungal Sinusitis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2022;131(9):1021-1026. doi:10.1177/00034894211052854

16. Radovani P, Vasili D, Xhelili M, Dervishi J. Orbital Complications of Sinusitis. Balkan Med J. 2013;30(2):151-154. doi:10.5152/balkanmedj.2013.8005

17. Lin GL, Chang HH, Lu CY, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcome of invasive fungal infections in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia patients in a medical center in Taiwan. Journal of Microbiology, Immunology and Infection. 2018;51(2):251-259. doi:10.1016/j.jmii.2016.08.011

18. Radici V, Brissot E, Chartier S, et al. Invasive Fungal Rhinosinusitis Due to Co-infection with Mucormycosis and Exserohilum rostratum in a Patient with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Clin Hematol Int. 2022;4(1-2):60-64. doi:10.1007/s44228-022-00009-3

19. Manchanda S, Semalti K, Bhalla AS, Thakar A, Sikka K, Verma H. Revisiting rhino-orbito-cerebral acute invasive fungal sinusitis in the era of COVID-19: pictorial review. Emerg Radiol. 2021;28(6):1063-1072. doi:10.1007/s10140-021-01980-9

20. Mohammadi K, Mohiyuddin SMA, Prasad KC, et al. Invasive Sinusitis Presenting with Orbital Complications in COVID Patients: Is Mucor the Only Cause? Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2024;76(1):55-63. doi:10.1007/s12070-023-04077-6

21. Patel VB, Patel A, Mishra G, Shah N, Shinde MK, Musa RK. Imaging spectrum, associations and outcomes in acute invasive fungal rhino-ocular-cerebral sinusitis in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. J Family Med Prim Care. 2023;12(6):1055-1062. doi:10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_1189_22

22. Kirszrot J, Rubin PAD. Invasive Fungal Infections of the Orbit. International Ophthalmology Clinics. 2007;47(2):117. doi:10.1097/IIO.0b013e31803776db

23. Coutel M, Duprez T, Huart C, Wacheul E, Boschi A. Invasive Fungal Sinusitis with Ophthalmological Complications: Case Series and Review of the Literature. Neuro-Ophthalmology. 2021;45(3):193-204. doi:10.1080/01658107.2020.1779315

24. Themes UFO. Cancer of the Nasal Vestibule, Nasal Cavity, Paranasal Sinuses, Anterior Skull Base, and Orbit: Surgical Management. Ento Key. Published March 14, 2020. Accessed March 30, 2024. https://entokey.com/cancer-of-the-nasal-vestibule-nasal-cavity-paranasal-sinuses-anterior-skull-base-and-orbit-surgical-management/

25. Chandler JR, Langenbrunner DJ, Stevens ER. The pathogenesis of orbital complications in acute sinusitis. Laryngoscope. 1970;80(9):1414-1428. doi:10.1288/00005537-197009000-00007

26. Velasco e Cruz AA, Demarco RC, Valera FCP, dos Santos AC, Anselmo-Lima WT, Marquezini RM da S. Orbital complications of acute rhinosinusitis: a new classification. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;73(5):684-688. doi:10.1016/s1808-8694(15)30130-0

27. Krohel GB, Krauss HR, Winnick J. Orbital Abscess: Presentation, Diagnosis, Therapy, and Sequelae. Ophthalmology. 1982;89(5):492-498. doi:10.1016/S0161-6420(82)34763-6

28. Evaluation and Management of Orbital Subperiosteal Abscess. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Published July 1, 2009. Accessed March 28, 2024. https://www.aao.org/eyenet/article/evaluation-management-of-orbital-subperiosteal-abs

29. Aryasit O, Aunruan S, Sanghan N. Predictors of surgical intervention and visual outcome in bacterial orbital cellulitis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100(25):e26166. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000026166

30. Presutti L, Lucidi D, Spagnolo F, Molinari G, Piccinini S, Alicandri-Ciufelli M. Surgical multidisciplinary approach of orbital complications of sinonasal inflammatory disorders. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2021;41(2 Suppl 1):S108-S115. doi:10.14639/0392-100X-suppl.1-41-2021-11

31. Lackner N, Posch W, Lass-Flörl C. Microbiological and Molecular Diagnosis of Mucormycosis: From Old to New. Microorganisms. 2021;9(7):1518. doi:10.3390/microorganisms9071518

32. Otte BP, Harris JP, Schulte AJ, Davies BW, Brundridge WL. Fusobacterium necrophorum Orbital Cellulitis With Intraconal Abscess. Cureus. 2023;15(7):e41415. doi:10.7759/cureus.41415

33. Emard A, Long B, Birdsong S. A 19-Year-Old Male With Orbital Cellulitis and Abscess Due to Fusobacterium necrophorum With Chronic Aspergillosis Resulting in Orbital Compartment Syndrome. Cureus. 2023;15(10):e47061. doi:10.7759/cureus.47061

34. Fungal culture - Aspergillus and Aspergillosis. Accessed March 28, 2024. https://www.aspergillus.org.uk/diagnosis/fungal-culture/

35. Chen SCA, Halliday CL, Hoenigl M, Cornely OA, Meyer W. Scedosporium and Lomentospora Infections: Contemporary Microbiological Tools for the Diagnosis of Invasive Disease. J Fungi (Basel). 2021;7(1):23. doi:10.3390/jof7010023

36. Orbital Infections and Differential Diagnoses. Accessed March 28, 2024. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/784888-differential?form=fpf

37. Wladis EJ, Tomlinson LA, Moorjani S, Rothschild MI. Serologic Evaluations in the Distinction Between Sinusitis-Related Orbital Cellulitis and Periorbital Necrotizing Fasciitis. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2023;39(6):599-601. doi:10.1097/IOP.0000000000002437

38. Jun P, Russell M, El-Sayed I, Dillon W, Glastonbury C. Invasive facial fungal infections: Orofacial soft-tissue infiltration in immunocompromised patients. Radiol Case Rep. 2015;8(2):813. doi:10.2484/rcr.v8i2.813

39. Indiran V. “Guitar pick sign” on MRI. Indian Journal of Ophthalmology. 2019;67(10):1737. doi:10.4103/ijo.IJO_404_19

40. Shamanna K, Krishnamurthy M, Deshpande GA. Our Experience of Surgically Managing Orbital Complications Due to Chronic Sinusitis: A Case Series. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2023;75(4):3874-3877. doi:10.1007/s12070-023-03924-w

41. Kim DH, Jeong JU, Kim S, Kim ST, Han GC. Bilateral Orbital Apex Syndrome Related to Sphenoid Fungal Sinusitis. Ear Nose Throat J. 2023;102(12):NP618-NP620. doi:10.1177/01455613211024768

42. Hersh CM, John S, Subei A, et al. Optic Neuropathy and Stroke Secondary to Invasive Aspergillus in an Immunocompetent Patient. Journal of Neuro-Ophthalmology. 2016;36(4):404. doi:10.1097/WNO.0000000000000361

43. Ashraf DC, Idowu OO, Hirabayashi KE, et al. Outcomes of a Modified Treatment Ladder Algorithm Using Retrobulbar Amphotericin B for Invasive Fungal Rhino-Orbital Sinusitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2022;237:299-309. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2021.05.025

44. Malleshappa V, Rupa V, Varghese L, Kurien R. Avoiding repeated surgery in patients with acute invasive fungal sinusitis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;277(6):1667-1674. doi:10.1007/s00405-020-05879-y

45. Smith C, Lee SC. Current treatments against mucormycosis and future directions. PLoS Pathog. 2022;18(10):e1010858. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1010858

46. Adulkar NG, Radhakrishnan S, Vidhya N, Kim U. Invasive sino-orbital fungal infections in immunocompetent patients: a clinico-pathological study. Eye (Lond). 2019;33(6):988-994. doi:10.1038/s41433-019-0358-6

47. Baek J, Park MJ, Lee HY, Kang S. Raoultella Ornithinolytica in a Healthy, Young Person: Rapidly Progressive Sinusitis with Orbital and Intracranial Involvement. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2023;10(10):003987. doi:10.12890/2023_003987

48. Lee A, Ellul D, Sommerville J, Earnshaw J, Sullivan TJ. Bony orbital changes in allergic fungal sinusitis are reversible after treatment. Orbit. 2020;39(1):45-47. doi:10.1080/01676830.2019.1576740

49. Abussuud Z, Ahmed S, Paluzzi A. Surgical Approaches to the Orbit: A Neurosurgical Perspective. J Neurol Surg B Skull Base. 2020;81(4):385-408. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1713941

50. Agarwal P, Sharma D. Total eyelid complex sparing orbital exenteration for mucormycosis. Trop Doct. 2022;52(1):38-41. doi:10.1177/00494755211041865

51. Salgado-López L, Campos-Leonel LCP, Pinheiro-Neto CD, Peris-Celda M. Orbital Anatomy: Anatomical Relationships of Surrounding Structures. J Neurol Surg B Skull Base. 2020;81(4):333-347. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1713931