Corneal Donation

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Corneal donation is the process of screening a corneal donor, recovering the corneal tissue, and preparing it for transplant. This process involves many evidence-based procedures to maximize the safety and effectiveness of the transplant. Each step is designed to reduce the risk of disease transmission through transplant surgery, while optimizing tissue quality to reduce the risk of transplant failure. Though corneal transplant surgeries are highly effective, they depend on the donated supply of tissue. Currently there is a global shortage of donated corneal tissue due primarily to limited healthcare infrastructure in much of the world, as well as cultural and social barriers that curb donations.

From Death to Consent to Medical Review of the Donor

The corneal donation process begins when an eye bank receives a call from a hospital, organ procurement organization, or other third party that someone who meets preliminary criteria for donation has died. A cornea’s viability has a limited lifespan since tear production stops at death, and a longer death-to-preservation time (DTPT) risks a failed transplant. While the U.S. standard is to recover corneas within 8 hours of death, it has been found that donor corneas with DTPT up to 10 hours can be utilized. [1][2] During this time, the eye bank needs to contact the next of kin, obtain informed consent, and recover the tissue. In cases where an autopsy is needed, often corneal tissue can be collected prior to the autopsy.

Some countries have an “opt-out” policy, which means that everyone is legally considered to have provided consent for organ/tissue donation unless the individual specifically opted out prior to death. Otherwise in countries that follow an opt-in policy, if the donor had not provided consent for tissue donation prior to death, consent must be obtained from next of kin.[3] The eye bank will also contact them to obtain a medical-social history, which helps the eye bank make a donor eligibility determination. Finally, the eye bank obtains relevant medical records from the hospital, paying close attention to the cause of death, any administered medications, and the circumstances of their death in order to ensure the tissue is safe and suitable for transplant.

In many countries, eye banks collaborate with organ procurement organizations (OPOs) that recover organs from deceased donors for transplantation. OPOs assess donor potential, collect clinical information, and follow national policies to determine whether someone is a suitable donor. There is a comprehensive uniform eye donor screening to avoid transmission of any infections or disease from donor to recipient.

Donor Screening

Extensive demographic and medical/social information is gathered regarding the donor, including the following:

- Origin of referral (hospital, funeral home)

- Donor's name, sex, and age

- Cause, Time, and Date of Death

- Whether informed consent was obtained, and for what tissues

- Post-mortem report (if autopsy performed)

- Past medical/social history (including history of any contraindications), including transfusion or infusion history

Contraindications

Donor age

- Donor age as an indicator of quality of donor cornea remains a topic of debate. There is no standard upper or lower age limit in countries such as India, Israel, the United Kingdom, and United States, though some eye banks have historically had upper age limits of 65 years.[4][5][6][7][8]

Risk of infectious disease

- Tissue from patients exhibiting risk factors for, clinical evidence of, or physical evidence of relevant communicable disease and high-risk behavior associated with relevant communicable disease may not be suitable for transplant. These possible contraindications include:

- Rabies, Hepatitis B, Hepatitis C, Creutzfeldt-Jacob Disease, Retinoblastoma, Bacterial/ fungal keratitis, Bacterial/ fungal endophthalmitis, HIV, Herpes Simplex Virus, Prion Disease, Human T-Cell Lymphotrophic Virus (HTLV), Ocular Adenocarcinoma, Malignant Tumors of Anterior Segment, Reye Syndrome, Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis, Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, Leukemias, Active disseminated lymphomas, Active infectious endocarditis, active septicemia, Dementia, Down Syndrome, Congenital Rubella, Recipient of non-synthetic dura mater graft, Neurological Diseases of unknown cause.[7]

- Diseases that have been confirmed and proven to be transmissible through corneal transplantation include rabies, Creutzfeldt-Jacob Disease (CJD), Hepatitis B, Herpes Simplex Virus, Cytomegalovirus (CMV), Malignancies (Adenocarcinoma, Retinoblastoma, Melanoma, Lobular Carcinoma), Acanthamoeba, and Ocular Bacterial Infections[9][10]

- To date, there has never been a reported case of disease transmission of HIV, Hepatitis C, HTLV-1 and -2, West Nile, Ebola, Zika, or Vaccinia viruses via corneal transplant surgery[11][9]

- COVID-positive donors are frequently disqualified. However, thus far there is limited evidence to definitively state transmission through corneal transplant.[11]

- Rabies, Hepatitis B, Hepatitis C, Creutzfeldt-Jacob Disease, Retinoblastoma, Bacterial/ fungal keratitis, Bacterial/ fungal endophthalmitis, HIV, Herpes Simplex Virus, Prion Disease, Human T-Cell Lymphotrophic Virus (HTLV), Ocular Adenocarcinoma, Malignant Tumors of Anterior Segment, Reye Syndrome, Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis, Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, Leukemias, Active disseminated lymphomas, Active infectious endocarditis, active septicemia, Dementia, Down Syndrome, Congenital Rubella, Recipient of non-synthetic dura mater graft, Neurological Diseases of unknown cause.[7]

Potentially High-Risk Populations

- Though specific eligibility criteria vary from country to country, the following categories of patients are frequently disqualified from corneal donation due to concern for possible infectious disease transmission:[7][12]

- Men who have sex with men

- Intravenous drug users

- People who have been incarcerated

- Young children of HIV-positive mothers

- Immigrants from certain countries

Physical Inspection of the Donor

If there are no medical or social contraindications, an eye bank technician will travel to the donor’s location, which is typically a hospital or morgue, to recover their corneas. The technician may be required to physically inspect the donor from head-to-toe, looking for physical signs of potentially transmissible diseases or high-risk behavior, including needle-tracks as evidence of IV drug use, recent tattoos, lymphadenopathy or oral thrush, or "physical evidence of anal intercourse.”[7]

Infectious disease screening tests

Serological testing is performed using donor blood collected during tissue procurement, or shortly before time of death[13]. The technician draws a blood sample to be tested for antibodies and/or antigens for diseases which may include HIV-1 and -2, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, syphilis and other blood-borne diseases.[14] HTLV-1 antibody testing may be performed for donors living in, or originating from, high-incidence areas — such as the Caribbean Basin, Central and Southern Africa, South Japan, Central and South America, and certain regions of Iran and Melanesia — or with sexual partners or parents from these areas.[15] Since the cornea does not contain blood vessels, donors and recipients do not need the same blood type.[16]

Obtaining/ Recovering the Corneal Tissue

The technician removes the entire eye using sterile technique and from there, the cornea. Afterwards, the cornea is placed in a storage medium to keep the tissue viable. Optisol-GS, which contains antibacterial supplementation, is the most common corneal storage medium in the U.S, though addition of amphotericin B has been suggested for improved activity against fungal infection.[17]

Evaluation of the Tissue

After preliminary screenings, eye banks will use imaging techniques to assess the quality of the corneal tissue. A slit-lamp exam is performed to evaluate for issues that may compromise the tissue’s viability, including corneal edema, scarring, arcus, pterygia, neovascularization, striae, central guttata, and infiltrates.[7]

Other techniques include:

- Specular microscopy to examine endothelial cell viability and morphology. Eye banks usually require a minimum endothelial cell density of 2,000 – 2,200 cells/mm^2 for the longest possible graft survival. Morphology assessment estimates the endothelial cells’ pleomorphism (deviation from hexagonality) and polymegathism (variation in cell area).[18]

- Pachymetry uses a probe to measure the thickness of the cornea. Eye banks use this technique to detect corneal swelling, like in Fuchs’ dystrophy.[14]

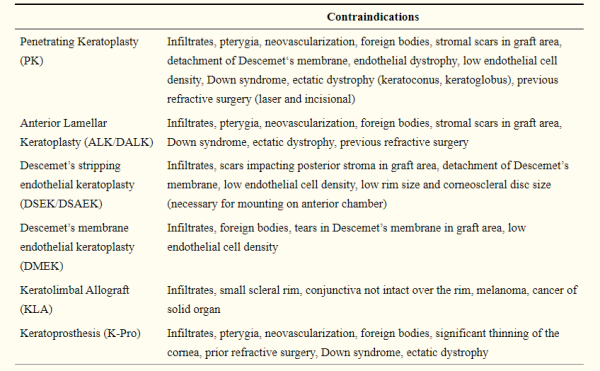

Different types of corneal transplants involve transplanting different aspects of the cornea, and different types of transplants have slightly different criteria for tissue eligibility.

- Penetrating Keratoplasty (PK): all of the layers of a patient’s cornea are replaced. All layers of the cornea must be healthy and clear in order to be suitable for use in PKP.[14][19]

- Anterior Lamellar Keratoplasty / Deep Anterior Lamellar Keratoplasty (ALK/DALK): This procedure involves transplant of only the anterior layers of the cornea, not including Descemet’s membrane or the endothelium. Thus, the donor must have healthy stroma, but endothelial quality is less relevant. One study found that qualities that make for appropriate and safe donor tissue include: donor age ≤ 88 years, post-mortem time ≤ 63 h, overall preservation time ≤ 14 days for cold storaged donor tissue and ≤35 days for organ culture, and preservation time after split prior to grafting ≤96 h.[20]

- Endothelial keratoplasty (DSAEK/DSEK/DMEK): Only the innermost layers of the cornea are transplanted (endothelium, Descemet’s membrane, and possibly posterior stroma). Endothelial cell counts and specular microscopy must be within an acceptable range, but anterior stromal disease is not a contraindication to surgery.

Release, Storage, and Transportation of the Tissue

If the corneal tissue is found to be suitable for transplant, it is packed in ice to ensure it remains between 2-8 degrees Celsius without freezing. Each cornea is labeled with a unique identification number so that the eye bank can track the tissue from donor to recipient. FDA guidelines state that corneas can only be preserved in solution for a maximum of 14 days. The solution is a combination of chondroitin sulfate, additional antioxidants, energy sources, and nutritive substrates. The eye is then preserved through organ culture or cryopreservation to ensure that the corneal endothelium is viable by the time transplant occurs.[21]

Organ culture puts the eye in a special solution (eyes are rinsed with saline, placed in povidone-iodine solution, and suspended in Eagle’s minimum essential medium) to keep eye tissue healthy and to prevent degradation. If organ culture is used, the tissue can be used 7 days after recovering. This practice is most commonly used in European eye banks. In contrast, cryopreservation (or flash freezing) is done if the tissue will be used months later and involves storing the tissue at temperatures below −80°C.[19][22] While more of an opinion than a practice rooted in scientific evidence, surgeons typically refrain from using corneas preserved for longer than 7 days.[23]

Global Perspective: Principles of Corneal Donation across Countries

Though demand for corneal transplant is worldwide, most countries lack the healthcare infrastructure needed for corneal donation.

The following are some important facts:

- Per year, approximately 185,000 corneal transplants are performed in 116 countries and 284,000 corneas are procured in 82 countries, with 55% of all corneas being procured in the US and India.[24]

- Globally, the top indications for corneal transplantation were Fuchs dystrophy, keratoconus, and sequelae of infectious keratitis.

- Order of corneal transplants per capita, starting with the highest: United States, Lebanon, Canada.

- The countries that exported the most donor corneas were the United States and Sri Lanka.

- About 53% of the world’s population lacks access to corneal transplantation. There is about only 1 cornea available for 70 needed.

- There are cultural differences that impact the amount of domestic corneas vs imported tissue from other countries. For example, the situation of eye banking and corneal donation in the Middle East varies, and may be dependent on local religious guidance as a study showed the most common motive for donation was the religious belief of doing good and being charitable with their body organs. [25] In addition, Japan has had very low organ and tissue donation rates due to lack of knowledge about deceased organ donation and transplantation, religious and cultural perspectives, and mistrust about the process.[26]

List of Major International Eye Bank Associations

- European Eye Bank Association (EEBA) - https://www.eeba.eu/home

- Eye Bank Association of Australia & New Zealand (EBAANZ) - https://ebaanz.org/

- Association of Eye Banks of Asia (AEBA) - https://eyebankingasia.org/

- Eye Bank Association of India (EBAI) - https://www.ebai.org/

- Pan-American Association of Eye Banks - Asociación Pan Americana de Bancos de Ojos (APABO)

- The Eye Bank Association of America (EBAA) - https://restoresight.org/

References

- ↑ Mohamed A, Chaurasia S, Garg P. Outcome of transplanted donor corneas with more than 6 h of death-to-preservation time. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2016;64(9):635–638. https://doi.org/10.4103/0301-4738.194338

- ↑ Rocky Mountain Lions Eye Bank, Coroner Education Module. Available from: https://corneas.org/coroner-education-work-with-coroners. Accessed September 1, 2021.

- ↑ Dimitry M, Lee H. Recent change in law and corneal transplantation in the UK. Eye. 2020;35:1524-1525.

- ↑ Arya SK, Raj A, Deswal J, Kohli P, Rai R. Donor demographics and factors affecting corneal utilisation in Eye Bank of North India. International Ophthalmology. 2021; 41(5):1773–1781. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10792-021-01736-x

- ↑ Katvan E, Doron I, Ashkenazi T, et al. Age limitation for organ transplantation: the Israeli example. Age and Ageing. 2017; 46(1): 8–10. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afw162

- ↑ Royal College of Ophthalmologists. Standards for the retrieval of human ocular tissue used in transplantation, research and training. 2008. http://bmec.swbh.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/RETRIEVAL-OF-HUMAN-OCULAR-TISSUE.pdf. Accessed December 9, 2021.

- ↑ Jump up to: 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Eye Bank Association of America. Medical Standards. 2020. https://restoresight.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Med-Standards-June-20-2020_7_23.pdf. Accessed May 4, 2021.

- ↑ Group CDSI. The effect of donor age on corneal transplantation outcome: Results of the Cornea Donor Study. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(4):620.

- ↑ Jump up to: 9.0 9.1 Dubord PJ, Evans GD, MacSai MS, et al. Eye banking and corneal transplantation communicable adverse incidents: Current status and project NOTIFY. Cornea. 2013;32(8):1155–1166. doi: 10.1097/ico.0b013e31828f9d64.

- ↑ Drury D. Safety Aspects in Ocular Donation. 14th Congress of the International Society for Organ Donation & Procurement; 2017. Available from: https://restoresight.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/20170906-Safety-Aspects-in-Ocular-Donation.pptx. Accessed October 25, 2021.

- ↑ Jump up to: 11.0 11.1 Toro M, Choragiewicz T, Posarelli C, Figus M, Rejdak R. Early impact of covid-19 outbreak on the availability of cornea donors: warnings and recommendations. Clin Ophthalmol. 2020;14:2879–2882.

- ↑ Puente MA, Patnaik JL, Lynch AM, et al. Association of Federal Regulations in the United States and Canada With Potential Corneal Donation by Men Who Have Sex With Men. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2020;138(11):1143–1149. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2020.3630

- ↑ Lambert N, Chamberlain W. The structure and evolution of eye banking: a review on eye banks’ historical, present, and future contribution to corneal transplantation. J Biorepository Sci Appl Med. 2017;5:23–40. doi:10.2147/BSAM.S114197

- ↑ Jump up to: 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Moshirfar M, Odayar VS, McCabe SE, Ronquillo YC. Corneal Donation: Current Guidelines and Future Direction. Clin Ophthalmol. 2021;15:2963-2973 https://doi.org/10.2147/OPTH.S284617

- ↑ European Eye Bank Association (EEBA). Minimum Medical Standards; 2020. Available from https://www.eeba.eu/files/pdf/EEBA%20Minimum%20Medical%20Standards%20Revision%205%20Final.pdf. Accessed October 25, 2021.

- ↑ Dunn SP, Stark WJ, Stulting RD, et al. The Effect of ABO Blood Incompatibility on Corneal Transplant Failure in Conditions with Low-risk of Graft Rejection. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 2009; 147(3):432-438.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2008.09.021

- ↑ Layer N, Cevallos V, Maxwell AJ, Hoover C, Keenan JD, Jeng BH. Efficacy and safety of antifungal additives in Optisol-GS corneal storage medium. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014 Jul;132(7):832-7. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2014.397. PMID: 24789459.

- ↑ Schroeter J, Rieck P. Endothelial evaluation in the cornea bank. Dev Ophthalmol. 2009;43:47-62. doi: 10.1159/000223838. PMID: 19494636.

- ↑ Jump up to: 19.0 19.1 Armitage WJ. Preservation of human cornea. Transfusion Med Hemother. 2011;38:143–147. doi:10.1159/000326632

- ↑ Schaub, F., Enders, P., Adler, W. et al. Impact of donor graft quality on deep anterior lamellar Keratoplasty (DALK). BMC Ophthalmol. 2017;17:204. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12886-017-0600-6

- ↑ Lass JH, Szczotka-Flynn LB, Ayala AR, et al. Cornea preservation time study: methods and potential impact on the cornea donor pool in the United States. Cornea. 2015;34(6):601–608. doi:10.1097/ICO.0000000000000417

- ↑ Baust JG, Gao D, Baust JM. Cryopreservation: an emerging paradigm change. Organogenesis. 2009;5:90–96. doi:10.4161/org.5.3.10021

- ↑ Rosenwasser GO, Szczotka-Flynn LB, Ayala AR, et al. Effect of cornea preservation time on success of descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017;1401–1409. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2017.4989

- ↑ Gain P, Jullienne R, He Z, Aldossary M, Acquart S, Cognasse F, Thuret G. Global Survey of Corneal Transplantation and Eye Banking. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016 Feb;134(2):167-73. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2015.4776. PMID: 26633035.

- ↑ Latifa F. Alanazi, Shaikha H. Aldossari, Mohammed A. Gogandy, Ghazai A. Althubaiti, Beshayer F. Alanazi, Abdullah M. Alfawaz. Attitude, beliefs and awareness towards corneal donation in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Journal of Ophthalmology. 2019;33(2):121-129, ISSN 1319-4534, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjopt.2019.02.003.

- ↑ Murakami M, Fukuma S, Ikezoe M, Izawa S, Watanabe H, Yamaguchi H, Kitazawa A, Takahashi K, Natsukawa S, Fukuhara S. Knowledge Does Not Correlate with Behavior toward Deceased Organ Donation: A Cross-Sectional Study in Japan. Annals of transplantation. 2020. 25:e918936. https://doi.org/10.12659/AOT.918936